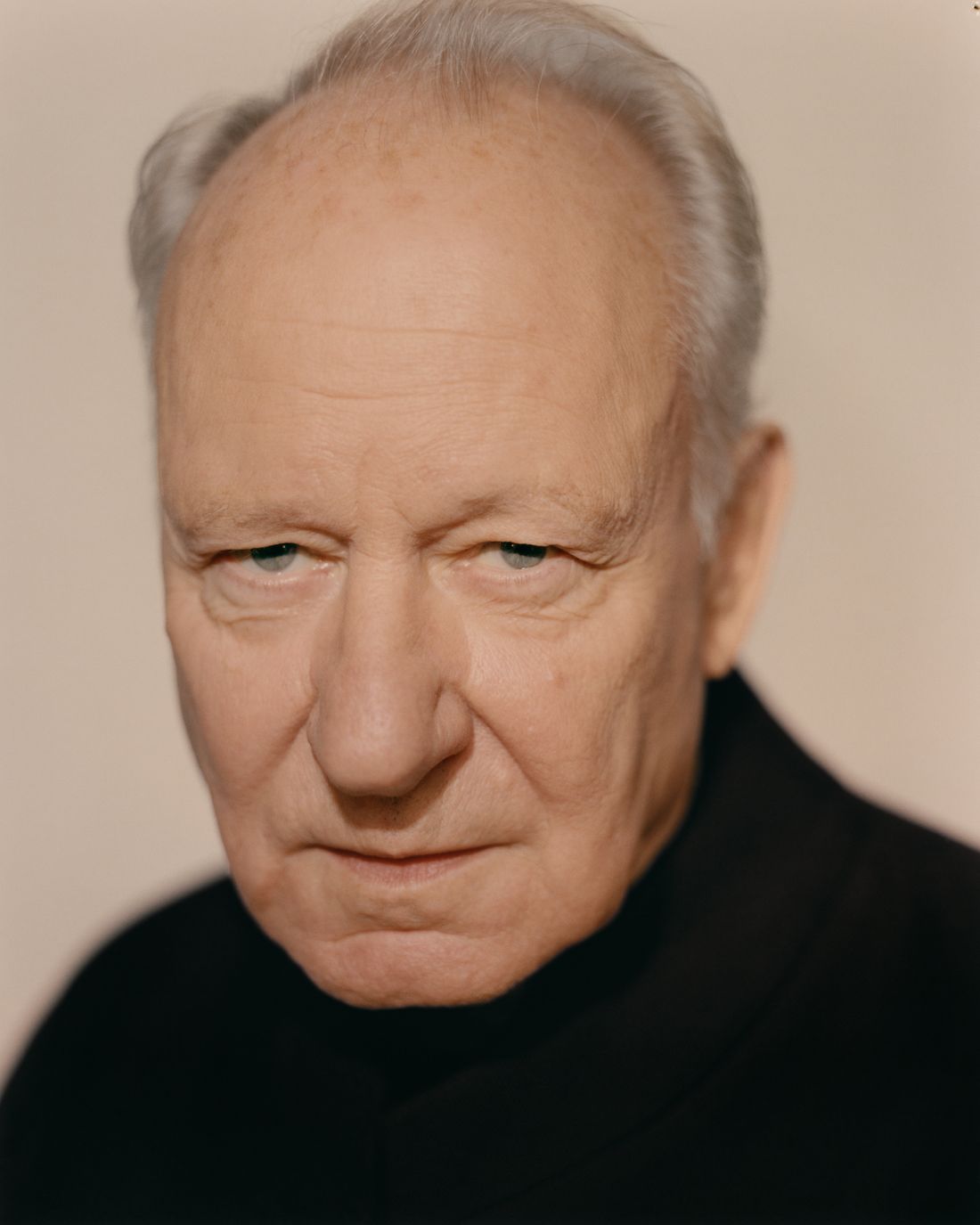

Stellan Skarsgård arrived at the Ritz-Carlton lobby restaurant a few minutes late because his son, Gustaf, had just watched his performance in Joachim Trier’s film, Sentimental Value. Gustaf playfully accused him of portraying himself, and Stellan admitted he recognized the similarities. In the film, Skarsgård plays a veteran director attempting to bond with his daughter by casting her in his latest project. Many believe Sentimental Value could finally earn him an Oscar nomination after a remarkable six-decade career that includes work with Lars von Trier and blockbuster franchises like Thor, Mamma Mia!, and Pirates of the Caribbean. There’s a quiet enjoyment that radiates from Skarsgård whenever he’s on screen. Remarkably, he’s remained vital even after suffering a stroke three years ago, which delayed filming for the second season of Andor and Dune: Part Two. He jokes that he feels like he’s ‘living on borrowed time’ now, acknowledging both his age – 74 – and a previously ‘naughty’ lifestyle.

Stellan Skarsgård:Have you seen the film?

I need to see the film before I can commit to the assignment. I was happy to meet with you either way, but it’s definitely a bonus if the movie is something I enjoy. It’s simply easier to promote a film when you genuinely like it.

People often ask how I can promote a film I dislike. It’s simple – my contract requires promotion. I always tell the producer I’ll do it, but I refuse to pretend it’s good. I’m honest about my dislike, and they get so worried they keep me away from the press!

In the film Sentimental Value, I play a well-known director who may be making his final movie. It’s a project I’m working on with one of my daughters, and our relationship is complicated. The interviewer asked me how my own life experiences connected to this role. Throughout my career, I’ve mostly chosen projects that simply appealed to me, or ones with a talented director or a fascinating, if flawed, concept. I’d been hoping to work with Joachim Trier for a while, and it felt like the right time when he finally reached out.

So, did I tell him? Yes, I did, eventually. I deliberately acted a little distant for about a week. Then we had lunch and talked about the movie. He offered to pay, but I insisted on paying myself. It was a clumsy way of showing I’m independent and don’t fall for flattery—even though I definitely was flirting back! Honestly, it was a fantastic role, and he’s a truly gifted director. So of course, I would have accepted his offer.

I was trying not to get my hopes up. I didn’t want to seem overly excited and risk ruining things. He’s a talented director, but even skilled people can make mistakes. I generally don’t get overly enthusiastic about work. I enjoy a good meal, but landing a role just makes me anxious. Whenever I accept a job, I immediately worry about all the work, stress, and the possibility of failing.

Throughout your career, you’ve worked with many directors. When developing the character of Gustav, what was essential for you to understand about him? Initially, I thought about directors I admired and perhaps even those I felt I had a past with, but I quickly focused on understanding his filmmaking style. I pictured a European director from the 1960s – someone known for striking, often dark visuals. That idea really excited me. The script didn’t fully flesh out Gustav, so I had to create balance, especially considering his flaws and terrible actions. It was important to make him relatable and help the audience understand why he behaves the way he does – that his actions, however misguided, stem from a twisted form of love. He simply lacks the emotional skills to navigate his relationship with his daughter.

Talking about acting is difficult because there’s so much I still have to learn. The most powerful and believable moments often happen in ways you can’t explain, and it’s hard to pinpoint exactly where they come from.

Does having too much knowledge, or even trying to gain it, become a problem? I avoid creating detailed character histories because they limit possibilities. People are incredibly complex, and defining a backstory actually simplifies them. Some actors try to define their characters by saying what they wouldn’t do, but I question how they can be so sure. This kind of rigid thinking stifles improvisation, and that’s a real danger – it destroys the very essence of what makes movies exciting.

With eight children of your own, did your experiences as a parent influence how you approached making this film? I didn’t consciously plan for it to, but watching the finished film, I realize there’s a lot of my own life reflected in it. My son, Alexander, saw it at the Telluride Film Festival and was deeply moved – he came out and just hugged me.

The movie explores how artists often prioritize their work and self-image, which can damage their personal relationships. Unlike many professions, like accounting, an artist’s work is deeply personal – they bring themselves and their experiences to everything they create. Balancing this intense focus with family life is challenging. Artists may feel that dedicating themselves to fatherhood means sacrificing their creative drive and potential.

Is it because you’re only seen as ‘Father’ now? No, it’s because you’ve changed into someone else. It’s like your perspective and actions would be different. You need your passions – they inspire you. And you’re more engaging for the kids when you come home with a story to tell, a story you wouldn’t have if you hadn’t experienced something stimulating. I’m just trying to explain my side of things. I have a strong relationship with my kids – I wouldn’t have dedicated fifty years to them if I didn’t. But they don’t respect me simply because I’m their father, and that’s ridiculous. Respect shouldn’t be automatic just because of a family connection.

Just five?[Laughs.] Well, I was sleepier. They don’t have to put me on a pedestal or anything.

It seems you believe respect shouldn’t be automatically given simply because you’re someone’s father. And you’re right – you believe respect should be earned through good actions, ideas, or creations. You shared a story about your son, Alexander, recalling you often being naked when he was growing up. When he told this story on Conan, the host joked about the danger of cooking while unclothed. You actually appreciated Alexander’s willingness to playfully tease you, seeing it as a sign of a healthy, open relationship where he feels comfortable joking about anything.

I had a very loving relationship with my father, though he was a complex man with his share of imperfections. He suffered a stroke at 70, which left him in a wheelchair and with difficulty speaking. He could become easily frustrated and would sometimes shout my mother’s name, which caused some family tension, but I never stopped loving him. After a second stroke, I was with him as he lay dying, holding his head in my lap along with my siblings. When he passed away, I began to cry, and his mouth fell open. I instinctively kept closing and opening his mouth, then I called out my mother’s name, “Gudrun!” which triggered a fresh wave of tears. Surprisingly, everyone in the room started laughing, and I know my father would have appreciated the moment. He wasn’t one for formality or excessive respect, even in such a serious situation. It just wasn’t considered proper behavior around a deceased person, but he would have found the humor in it.

A lot of what makes a film special comes down to the director’s approach. In ‘Sentimental Value,’ the director, Gustav, always responds to the actress Rachel (Elle Fanning) with, “What do you think?” when she asks for guidance – it’s about letting the actor find their own way. I particularly admire directors like Lars and Joachim Trier because they present their vision without being overly controlling. They offer suggestions, like trying a different direction, and then let the camera follow, rather than dictating specific lines or emotions. They trust the actor to bring the character to life. Generally, directors don’t tell me how to act, because I feel I have a good understanding of my craft. They might ask for a faster or slower pace, but ultimately, freedom is essential for creating a believable character, and that’s the kind of director I prefer.

I collaborated with Miloš Forman on the film Goya’s Ghosts. Natalie Portman once asked him a question, and he playfully replied, “Why? I chose you for the role! It’s your responsibility to know. Now, let’s talk about where we’re having dinner tonight.” That really captures his personality – he was a director who kept things light and prioritized enjoying life.

I first encountered Lars von Trier’s work with Breaking the Waves, which I saw in high school, and it really impacted me. I remember reading the script and thinking, ‘Finally, a love story that feels real.’ It truly is about love, not just about physical relationships or marriage. The character does everything out of love, and he loves her too—so much so that he encourages her to be with other people, fearing she’ll leave him because of his paralysis. She sees no future with him, but she remains devoted. She has affairs and then tells him about them—it’s incredibly tragic. I traveled to Copenhagen to meet Lars, but he’d already cast another actress in the role.

Helena Bonham Carter was there too. When we arrived at his house, he immediately seemed to read my cues and told me he didn’t like being touched, specifically asking me not to hug him. Naturally, I hugged him anyway! He initially squirmed and tried to pull away, but eventually relaxed, and we’ve been hugging ever since.

Around this time, he was likely developing his Dogme 95 manifesto – a somewhat provocative set of rules intended to revitalize filmmaking. Did we ever discuss his approach to making movies or his overall philosophy? We could have, but we didn’t. He preferred to be directly involved and was very approachable. Helena seemed exhausted; she had a very early flight and was lounging on the sofa, still undecided. We were on our way to the airport when I told her she’d be crazy not to accept the opportunity.

Did you notice her being unsure about it? Yeah, it was a risky project at the time. The director was relatively unknown, and it involved a Swedish and Danish filmmaker. Their previous work was quite explicit, with a lot of nudity, which didn’t really align with what British audiences were used to. There were likely many reasons why she passed on it – she probably just didn’t like the idea. She didn’t accept the project. I later saw her at an Oscars party and, from a distance, she acknowledged she’d been right to hesitate, saying, “Yes, I knew, I knew, I knew!”

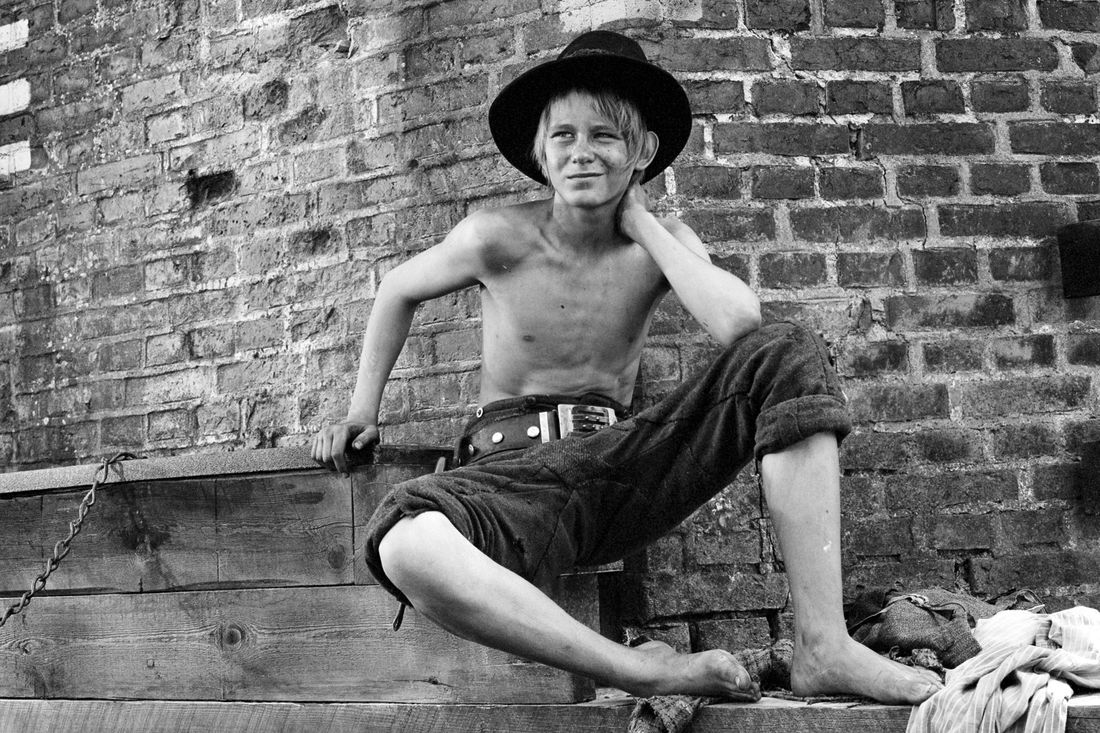

You became well-known very young thanks to the TV show ‘Bombi Bitt och Jag,’ where you played a character similar to a Swedish version of Huckleberry Finn. How did that sudden fame affect you emotionally? While you could have pursued more celebrity, you chose a different path. I was only 16 when the show aired, and everyone saw it. I received a lot of attention from fans, especially girls, which I enjoyed. However, I always felt a disconnect between my true self and the public image presented in the media, so I didn’t take the press seriously.

I was aware of that even back then. My family – my parents and siblings – really helped me stay grounded, telling me I wasn’t heading down the wrong path. But being a child star in Sweden is different. It’s hard to support a family that way. I only earned around 7,500 krona for the whole series, so there wasn’t any financial reason to get into trouble. You couldn’t even afford to, really.

You spent a large part of your twenties and thirties with the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. What led you to begin your career there? Well, it wasn’t really a choice I made. I’d been involved in amateur theater, and we had a group that did everything together before I started working on TV. After the TV show, I received theater offers and decided to leave school at 17. I took on small roles for years, and I always had work. Eventually, I started doing films. My first film was a sex comedy called Strandhugg i somras (Raid in the Summer) in 1972, but they ran out of funding during production, and I still haven’t been paid for it.

I appeared in a couple of erotic films. When I took on the first one, Anita: Swedish Nymphet, I believed it would explore a character’s psychological issues related to being a nymphomaniac, and I found that idea intriguing. However, after making the film, I realized it wasn’t really about that – it just focused on the sexual aspect, rather than the underlying psychology.

I tried acting again, this time fully aware of what the films were – essentially, exploitation films. That shattered any illusions I had. Afterward, I developed a real fear of the camera. I was so embarrassed by the poor quality of those movies that I avoided acting in films for about five years. It was similar to stage fright – a feeling of intense panic, like your head might explode, and complete memory loss. Even if you do manage to remember your lines, your voice comes out strained and weak, because you’re so tense and terrified. It was truly awful.

I got back to enjoying my work by making a student film with close friends and talented actors. Shortly after, I landed the role in The Simple-Minded Murderer, which won an award at the Berlin Film Festival. While in New York, I met Jeri Scott, who became my agent. It took her five years, but she eventually convinced me to move to Los Angeles. That’s how I got the part in The Hunt for Red October. I only worked for a day and a half on that film, but I earned more than I had in my entire career up to that point.

“How much did you get for it?” Someone asked. It was around $50,000 – a combination of an upfront payment and ongoing royalties. That’s when it hit me: “This is a good opportunity, and I should do it.”

You’ve collaborated with Lars von Trier on six films, starting with Breaking the Waves in 1996. What do you think has made that partnership so successful for so long? It comes down to a deep affection and acceptance of each other’s differences – which is essential for any strong relationship. Lars is incredibly intelligent, has a great sense of humor, and isn’t afraid to be vulnerable. That creates a safe environment on set. I remember on Breaking the Waves, he even had a sign that said, ‘MAKE MISTAKES.’ He’d ask if anyone had made one yet, and I’d say, ‘Not yet, but I’m working on it!’ He’s remarkably open-minded and free in his thinking. He once told me he’d finally figured out what kind of films he was meant to make.

“Yes, Lars, what kind of films do you make?”

“I make the film that hasn’t been made.”

“Exactly, Lars. That’s what you do.”

Many people, particularly in America, have a really negative view of him, seeing him as cruel and believing he deliberately makes the filmmaking process difficult for actors. They seem to think actors need to suffer to convincingly portray challenging roles – like needing to live as a murderer to play one. But actually, he’s a very kind person. He’s now dealing with Parkinson’s disease, and it’s unclear what the future holds.

I’d heard rumors about a film you were planning to make with him this summer, something about his Parkinson’s disease. Is that true? He hasn’t mentioned anything to me. He did have an idea for a film similar to the classic French film La Jetée – it’s made up of still photographs and is really beautiful. He thought he could film it at home, and that’s what he’s been discussing. I’d absolutely work with him on it; I’d say yes to anything he asked me to do.

Even if you didn’t like the script, would you still agree to be in the film? Yeah, because if it hasn’t been made yet, it probably deserves to be.

Someone mentioned I spent a day on the set of Dancer in the Dark, and it got me thinking about all the stories I’d heard. Apparently, Lars von Trier and Björk didn’t always see eye-to-eye, and I was asked what that was like to witness. Honestly, it was pretty surreal. I was relaxing at my summer house when the phone rang, and it was Lars himself!

“Hey, Lars, how’s it going?”

She’s completely lost it. She ripped up the only T-shirt we had, actually ate it, climbed a really tall fence, and ran off. It doesn’t look like she’s returning.

“Wow. Congratulations. You have full hands, I see.”

The production was temporarily paused for a few days. When I arrived for my shift, I was walking across the studio lawn when a car sped up and stopped. The door flew open, and the producer, Vibeke Windeløv, ran towards me, clearly upset. Even before she spoke, I could tell something was wrong.

Lars called again, explaining he’d figured out what was wrong. He said he went to Björk’s trailer and deliberately broke her large television, after which she became silent. The issue, he implied, stemmed from Björk’s lifelong need to control everything – particularly her creative work. Meeting Lars von Trier, a director known for his strong vision, meant she couldn’t dictate the film’s direction. It also seemed Björk was apprehensive about taking on a major role and succeeding, though ultimately, she was incredibly talented.

How should the working relationship be structured? It needs to be collaborative and built on trust, like with directors Joachim Trier or Lars von Trier, but ultimately, the director needs to be in charge. Think of it like a conductor – you can share your ideas, but you have to trust their final decision. Some believe conflict is necessary for good art, that it needs to be a struggle, but I disagree. You’ll naturally face difficulties in the creative process anyway, so there’s no need to intentionally create more.

It sounds like you strongly dislike being controlled or manipulated, particularly by a director. You believe you understand yourself and what motivates you better than anyone else, so attempts to manipulate you are unwelcome.

You suggested Ingmar Bergman was controlling. Was he hard to work with? Well, he wasn’t controlling as a director, but he was a controlling person in his personal life. He wielded power indirectly, making sure the right people were hired and the wrong ones were let go – essentially controlling people’s careers. That’s where the manipulation came in. When directing, though, he was very straightforward and concrete. He didn’t try to force a specific performance out of you; he was simply a skilled director.

You mentioned judging a director by whether they cut the camera away from you when you’re not talking. That approach feels very television-like – everything is laid out in a straightforward way, leaving little room for actors to interpret or add to the scene. Film, on the other hand, draws you in. Television scripts are so detailed that the information is all right there on the page, meaning the director and actors don’t have much impact. You could practically watch it while doing chores and still understand everything that’s happening.

When asked about his experiences with the TV shows he’s been in, he responded that he felt differently. He mentioned working on Chernobyl, calling it a peak achievement for HBO, created by Craig Mazin and Johan Renck. Then, Tony Gilroy, the creator of Andor, reached out to him. Initially hesitant about joining a Star Wars project, he was convinced by Gilroy’s vision for a more grounded and realistic story with complex characters. His main concern was a long-term commitment, so he asked Gilroy if he would be the showrunner and writer for the entire run. Gilroy couldn’t guarantee that, but promised two years. The actor jokingly asked if he could be killed off after two seasons if he wanted, and Gilroy agreed. He enjoyed working on Andor and could have continued for another season, but wasn’t necessarily looking to.

Many viewers connected the fictional massacre in Ghorman to the real-world situation in Gaza after the show’s second and final season. What are your thoughts on people drawing parallels between the show and current events, even though the show wasn’t directly inspired by that specific conflict? I believe that’s exactly how you should approach any piece of art – viewers bring their own experiences and find meaning within it. This show was actually written before the Trump presidency and even before the tragedies in Gaza. The unfortunate—but also positive—thing is that stories like this will always be relevant, no matter what’s happening in the world.

You generously donated a signed Mamma Mia! record last year to support humanitarian aid for Palestine. Some might see that as a politically sensitive act. Was it a difficult decision for you? Not at all. I was protesting even before the conflict in Gaza began, back in Sweden.

Even before the events of October 7th, there were fears of a major escalation. Discussions about forcibly displacing Palestinians – like sending them to Africa – and completely destroying Gaza had already begun. This wasn’t new; since 1948, there’s been a pattern of disproportionate response – for every Palestinian life lost, many more Palestinians would be killed, and their families’ homes would be demolished. We anticipated a large-scale attempt to destroy Gaza. I was even falsely accused of supporting antisemitism in a Swedish newspaper, a common occurrence. But these thoughts weigh on me constantly; I think about it every single night.

Ever since my stroke, I’ve noticed a real change in how I think and speak. It’s frustrating, but my arguments just don’t have the same strength they used to, and my words don’t come out as clearly. Honestly, it’s gotten to the point where I just don’t feel up to debating or even having a simple discussion with anyone. It’s like I’ve lost the ability to really ‘fight’ for my ideas.

Can you tell me about the stroke and how it’s affected you?I got really scared.

It happened three years ago, during the production of the first two episodes of Andor and the first two episodes of Dune. The timing worked out well, but I needed a workaround. They used earpieces with a prompter to feed me lines, but that wasn’t enough because I rely on my own natural pacing. So, they had to deliver their lines simultaneously with mine, allowing me to respond. It required a lot of practice for the person feeding me the lines – they had to be very quick and deliver the lines in a neutral tone.

Someone asked if a particular show was ‘Andor,’ but it was actually ‘Dune.’ People assume that not having much dialogue is easy, but there’s actually more work involved now. I’m finding it hard to remember names or even complete a simple thought. It’s incredibly frustrating when you lose your train of thought mid-sentence. Still, I’m grateful to be alive and able to work.

Did you ever wonder about the bigger questions in life? It would have been nice to, but I didn’t, because I already knew I was facing death. It wasn’t a surprise. Of course, I did think to myself, ‘This could be it.’ I just didn’t know how severe the stroke would be, or if I’d have more.

Has this role altered your perspective on your work as an actor? Not really. I felt good about my performance in this film. But you’re suggesting that it might have – that this experience has placed me in a new position as an actor, and that’s something to consider.

Honestly, it sounds like a really deep thing to go through. For me, it’s not death I worry about, but not truly living life to the fullest. That’s a real fear. And you know, being boring is a big one too! With eight kids, every time a new one came along, I wasn’t scared of things like Down syndrome or autism – I was terrified they’d be… dull. Thankfully, they all turned out to be anything but!

Some of my children are actors, and people have asked if that makes them ‘nepo babies.’ I actually see myself as the ‘nepo daddy’ – I benefit from their success and may even get opportunities because of them.

Has networking actually led to any job opportunities for you? I’m not sure. I haven’t received any recommendations, and that’s because I haven’t given any either. But my youngest son, Kolbjörn, who’s thirteen, is really affected by it. He gets upset when kids at school call him a ‘nepo baby.’ It’s made him feel isolated and he doesn’t have many friends. Kids can be really mean – or just unaware – and they seem to enjoy it online. But it’s frustrating because ultimately, you won’t get hired for anything worthwhile if you don’t have the skills and talent to back it up.

Was money a major factor in your choices? Not particularly. We have access to free education at all levels, and healthcare is also covered.

It’s great you’re all set up, and thank you for the congratulations. However, when a major studio makes an offer, I always ask for more – they can afford it! I’m happy to lower my rates for smaller, independent European films. Honestly, I’m not motivated by getting rich, just by spending what I earn. My family certainly helps with that! I’m not accumulating wealth, but I’m having a lot of fun. For example, did you hear about when I brought everyone with me to Italy while I was filming there?

I usually include them when I travel. And you really should bring your wife’s friends too, otherwise she’ll be stuck looking after everyone in a new city on her own. It’s good to have some of the kids’ friends along as well – they function best as a group. When I was filming the first Exorcist movie near Rome, we had 43 Swedes living nearby. As the lead, I worked twelve-hour days and didn’t see them much during the week, only on weekends. But the house was always full of life and parties. The film was very successful, though I didn’t have a huge amount of money left afterward. It was all worth it, though.

The initial version was directed by Paul Schrader, and it was actually pretty good. However, the producer was surprisingly unaware they’d hired both Schrader and Skarsgård. When it was finished, the film was a two-hour drama about a man struggling with a personal crisis, but they were expecting a horror movie. So, they completely reshot it with Renny Harlin and released that version first. It was strange because they used the same script, costumes, and makeup. I’d worked with Renny Harlin before and enjoyed it. He’s not as artistic as Paul Schrader, but he’s enthusiastic and really loves filmmaking, which is something you can appreciate. We had a good time on set, though I’m not sure how the final product turned out.

How much do you focus on the final product? Personally, I really enjoy the filming process itself. Being on set is where all the creativity comes alive. Once filming wraps, there’s not much I can do to change things – a lot is out of my control. But with movies, you have the option to move on if you’re not happy with how it turns out. That’s different from theater, where even if opening night is a failure, you’re still stuck performing the same show for months.

For me, the biggest challenge to creating truly great work today seems to be fear. It’s a complex thing, but I think it stems from being afraid of repercussions for expressing unpopular opinions, especially in the current climate. Or, it’s the worry about financial security. I was recently reminded of this while reading Daniel Kehlmann’s The Director, a novel about the filmmaker G.W. Pabst. He struggled in 1930s Hollywood because his artistic vision – very much rooted in German Expressionism – didn’t quite fit the commercial demands. He actually tried to return to America after going back to Germany to care for his mother, but he was also strongly opposed to the Nazi regime, which added another layer of complexity to his situation.

When war broke out, Pabst found himself stranded in Germany. The Nazis approached him, recognizing his talent as a director, and asked him to work for them. He initially refused to create propaganda, but they insisted he could film whatever he chose, as his cooperation alone would be beneficial to them. He ultimately agreed, which, while allowing him to continue his work, also served the Nazis’ purposes. This arrangement was crucial for his own survival, both emotionally and physically, and surprisingly, he enjoyed more creative freedom in Nazi Germany than he had in America. However, he carefully avoided addressing any political issues directly. It’s a complex situation.

What’s your take on that? He’s certainly not like Leni Riefenstahl. It’s disturbing to see her associating with former Nazis, though the situation is complex. The Soviet Union produced some incredible films in the 1960s, but financial constraints often lead to artistic censorship. True art needs freedom – it can’t be controlled or restricted, and it thrives on being unrestrained.

Entering the awards season with a film inevitably involves navigating a complex social and political landscape. The Oscars definitely serve a purpose – they’re beneficial for the film industry as a whole, and especially for independent films that might not otherwise get noticed. While it’s impossible to fairly compare art, the Oscars represent a lot of people sharing their opinions on the films they’ve seen, and I participate in the voting process myself each year. The biggest challenge is the cost – running a campaign is incredibly expensive. Luckily, our American distributors are covering those costs, as most European film companies simply couldn’t afford it.

Take Neon, for example – they’re a strong company with a real understanding of the film landscape and they’re willing to invest heavily in Oscar campaigns. Those campaigns, in many ways, were pioneered by Harvey Weinstein, who also helped many independent films gain recognition, though his actions also caused harm. He’d sometimes acquire numerous films, only to promote one while suppressing the others. The film industry often operates like old-fashioned horse trading – it’s not always straightforward, driven by both practical needs and the desire for profit. Despite all this, it still retains a bit of its original, lively, and somewhat unpredictable spirit.

Ultimately, it’s all just entertainment. When I was sixteen, I toured with a traveling vaudeville show, going to rural markets and fairs. I was the host, and I was quite well-known from a TV show at the time. The acts were classic vaudeville – a glass eater, a fire swallower, a ventriloquist, and a toothless stripper who was amazing. She once joked about another, even more low-rent show, saying they were the ‘artists’ compared to that one. Later, when I started working at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, I noticed people talking about art in the same dismissive way – claiming they were the real artists and anything else wasn’t.

Do you find yourself hoping each new acting role will finally bring a sense of satisfaction? As an actor, you’re essentially a tool for the director’s vision. However, all my characters, despite being different, share a common thread. When you truly connect with a role, your own personality inevitably shines through and leaves its mark on the work. I hope audiences can recognize my perspective on life and people when they watch my films. Though, it’s possible I’m still just a hired performer, blending into the background.

I grew up with a strong belief in equality, something my father taught me early on: everyone has equal worth. This belief shapes my support for things like free education, healthcare, and childcare – I believe our society has the resources to provide these for everyone. It’s frustrating because in America, people often mistakenly equate social programs with communism and believe capitalism automatically equals freedom. But true freedom isn’t just about allowing exploitation; it’s about ensuring everyone has the opportunity to thrive.

Did you ever take on roles that resonated with what you were going through personally, or helped you explore your own thoughts and feelings at the time?

When I was younger, I was very focused on keeping art pure and separate from everything else. I wouldn’t have considered doing something like Mamma Mia! Now, as I’ve gotten older, I’m more open to different kinds of projects. I don’t feel like my films need to have a strong, obvious message as much as they did when I was a more idealistic and opinionated filmmaker in my twenties. Back then, I was much more concerned with what the ‘point’ of a film was.

I remember the exact moment things shifted. Though, it’s possible my memory is playing tricks on me. I once played the role of Raoul Wallenberg, a man who rescued tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews during World War II. He was later captured by the Soviet Union and executed. Our play, Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, focused on the final three weeks of his freedom, a time when Budapest was in chaos. The German forces had withdrawn, and a local Nazi group called the Arrow Crosses had taken control. They were even more ruthless than the Germans, but less disciplined.

The movie was incredibly gritty and filmed on location in a historically impoverished neighborhood where some residents had actually lived as children during World War II. They treated me with a kind of reverence, almost like a legendary figure, often approaching me during nighttime filming and even offering me coffee laced with vodka to help me stay warm. I was so immersed in the experience that I barely slept, and I found myself wandering around cemeteries while slightly intoxicated. But the quality of the film itself became secondary; our priority shifted to authentically portraying the lives of the people we were filming. After that project, I needed a break from filmmaking. Nothing felt as meaningful, and suddenly, all movies just seemed like entertainment.

Fact-check: Alexander told Conan, “It’s not that big.”

Skarsgård plays Jan, an oil rig worker who marries Bess in a small, extremely religious town in the Scottish highlands. After they wed he becomes paralyzed in an accident. He encourages her to have sex with other men and tell him about it. The film is the beginning of Trier’s Golden Hearts trilogy with naive, doomed protagonists at the center.

Along with Thomas Vinterberg, von Trier wrote a manifesto with 10 vows of “Chastity” that included using handheld cameras and eschewing unnecessary props, lighting, and special effects to save cinema. (It was in that classic von Trier way, real and kind of a troll.) Breaking the Waves is considered a proto-Dogme film.

The role went to Emily Watson in her film debut. She was nominated for Best Actress at the Oscars.

Hans Alfredson based the film off of a chapter in his book An Evil Man. It won top honors at the Guldbagge Awards (the Swedish Oscars) including Best Actor for Skarsgard.

He won Best Actor at Berlinale.

He played Soviet submarine commander Captain Tupolev.

Skarsgård does a pinched “Lars voice” whenever he recalls conversations with the director.

Speaking through his production company Zentropa, Trier announced his Parkinson’s diagnosis in 2022. Earlier this year, his producer Louise Vesth said the director was admitted to a care facility.

A sci-fi short directed by Chris Marker, associated with the Left Bank of the French New Wave about a post-nuclear war time travel experiment.

Skarsgård plays the doctor that treats Björk’s character who suffers from a degenerative eye disease.

In an October 2017 Facebook post, Björk wrote she was sexually harassed by a “Danish director” widely presumed to be von Trier, saying that he made repeated sexual overtures and “wrapped his arms around me for a long time in front of all crew or alone and stroked me sometimes for minutes against my wishes” and then retaliated when she didn’t acquiesce to his desires. Von Trier denied the allegations, saying, “But we were definitely not friends. That’s a fact.”

In the same Facebook post, Björk addressed that rumor writing, “i have never eaten a shirt. not sure that is even possible.”

Skarsgård worked with Bergman on a televised play of L’École des femmes and a theater run of August Strindberg’s A Dream Play. In an interview this year at the Karlovy Vary film festival, Skarsgård called Bergman manipulative, adding, “He was a Nazi during the war and the only person I know who cried when Hitler died.”

The Empire learns there is a mineral at the center of the planet Ghorman, and begins to tighten control over the planet while allowing for a rebel presence in order to engineer a pretext for greater military force. What begins as a peaceful protest ends up known as the Ghorman massacre in episode 8.

In 2016 Skarsgård revealed that he got a vasectomy.

Kolbjörn currently stars on a horror show on SVT called Blood Cruise. Photos of him from the set recently went viral.

The film was intended to be a prequel to the original The Exorcist centered on Father Merrin, played by Skarsgård. The one with Harlin, titled Exorcist: The Beginning, was released in 2004; Schrader’s version, Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist, came out the following year.

The German filmmaker is best known for Nazi propaganda films like Triumph of the Will. After World War II, she was not charged with war crimes, but tried to distance herself from Nazi regime and the Holocaust. Susan Sontag notably had thoughts.

He’ll be campaigning for Best Supporting Actor.

Read More

- My Favorite Coen Brothers Movie Is Probably Their Most Overlooked, And It’s The Only One That Has Won The Palme d’Or!

- The 1 Scene That Haunts Game of Thrones 6 Years Later Isn’t What You Think

- Will there be a Wicked 3? Wicked for Good stars have conflicting opinions

- 3 Best Movies To Watch On Prime Video This Weekend (Dec 13-14)

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- LINK PREDICTION. LINK cryptocurrency

- World of Warcraft Decor Treasure Hunt riddle answers & locations

- Decoding Cause and Effect: AI Predicts Traffic with Human-Like Reasoning

- Landman Recap: The Dream That Keeps Coming True

- Thieves steal $100,000 worth of Pokemon & sports cards from California store

2025-10-22 16:03