Hayao Miyazaki doesn’t make a grand entrance – he simply shows up. This was how the director unexpectedly introduced himself to animation student David Encinas on the streets during the 1993 Annecy International Animation Film Festival. “My classmates were on the opposite side of the street, and all of a sudden, they started pointing,” Encinas recalls. “I turned my head and there was Miyazaki, standing next to me, waiting to cross.” The encounter felt just like the scene in My Neighbor Totoro, where the girls are waiting in the rain and a giant Totoro appears quietly.

Their interaction eventually sparked a discussion facilitated by a translator and an impromptu animation critic. This encounter ultimately led to his job on Miyazaki’s iconic film “Princess Mononoke” in 1997, which has been remastered and re-released in IMAX for the first time this week. Today, Encinas continues to animate and teach animation at Gobelins Paris. However, during the mid-’90s, he became one of the rare Western artists to work for Studio Ghibli, realizing an animator’s dream: collaborating on films by legendary creators like Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, while learning from Ghibli’s top executives. Upon his arrival after acquiring some professional experience, they made him begin anew, just as everyone else did: “Bouncing ball exercises and drawing hands,” Encinas reminisces. “And I was so thankful for that. In less than three months, I learned more than in all my years combined at Gobelins and Disney.

At Annecy, after Miyazaki had watched and provided feedback on Encinas’s animation reel using a translator, Encinas inquired directly about getting hired at Ghibli from Miyazaki. Miyazaki made one requirement clear: “Learn Japanese.” For the next two years, while he was working on The Goofy Movie and freelancing, Encinas used a portion of his early earnings for language lessons. He returned to Annecy in 1995, where he met Takahata, a colleague of Miyazaki’s. Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki recognized him from the meeting with Miyazaki, handed him his business card, and suggested he visit Japan to take Ghibli’s animation test. Encinas humorously notes, “I think he must have thought, ‘Oh my, he really did learn Japanese.’

Eager to make his move, Encinas journeyed to Tokyo during summertime, a place where Miyazaki demanded an animation layout from him by morning and feedback in the afternoon. As Miyazaki leafed through the pages, he mumbled softly: “Alright, initial part, looks decent enough…” Then, he extracted thin, almost translucent yellow sheets – popular among Japanese animators for corrections – and started sketching.

According to Encinas, as soon as Miyazaki began sketching, a divide became apparent to him. His education in Western animation and knowledge of anatomy were significantly different from what Miyazaki demanded. At that time, the studio was working on their most challenging project yet, Princess Mononoke, with drafts of the artwork already spread out on the studio’s tables. When he beheld the exceptional quality of the drawings, Encinas realized his skills weren’t up to par. However, they proposed training him under the guidance of their top animators.

At Studio Ghibli, the work environment emphasized learning, especially during their costliest and most demanding project yet. Hand-drawn animation is already a laborious and iterative process under ideal conditions, but the production of Princess Mononoke was a time marked by studio overwork, constant schedules, and looming deadlines. The studio invested an unprecedented amount of money and resources into this film that Miyazaki himself admitted he didn’t mind if it led to their bankruptcy. The staff were well aware of the situation: “If Princess Mononoke had failed,” Encinas says, “Ghibli would have closed.

Due to his lack of experience in Japanese and the complexity of the animator role, it was unlikely that he could be hired as a full-fledged animator. However, an entry-level position as an assistant handling tasks like in-betweens and clean-ups was possible. He started working on Princess Mononoke in mid-1997 and stayed with the company for two years. His main supervisor during this time was Ken’ichi Konishi, a key animator on Mononoke, who later became the animation director for Ghibli’s next film My Neighbors the Yamadas. Once a week, he collaborated with Yoshifumi Kondo, who was being groomed as Miyazaki and Takahata’s successor, before his unfortunate death due to overwork. Yasuo Ōtsuka, a mentor to multiple generations of Japanese animators including Miyazaki and Takahata, would visit once a week to assign exercises to Encinas and other newcomers at the studio. The feedback from everyone in the studio helped Encinas adjust his approach and career path, eventually leading him to teach Japanese animation methods at Gobelins Paris.

He remarks that at Disney, unlike what he experienced, an animator wasn’t teaching their assistant. Despite this, he feels the culture in Western studios differs and can sometimes lead to problems: “They’re focusing on their tasks, but they may not always understand its origin or destination.” The size of operations is also a factor. For instance, at studios like DreamWorks, different departments could be located in separate buildings, whereas for Hayao Miyazaki’s “Princess Mononoke,” everyone worked on the same floor, in the same room, collaborating closely. Even senior staff would participate in manual labor tasks, whether it was an animation director personally painting celluloid frames or key animators working on in-betweens and checking each other’s work. Encinas admits he can hardly imagine such collaboration happening at a large studio like Pixar.

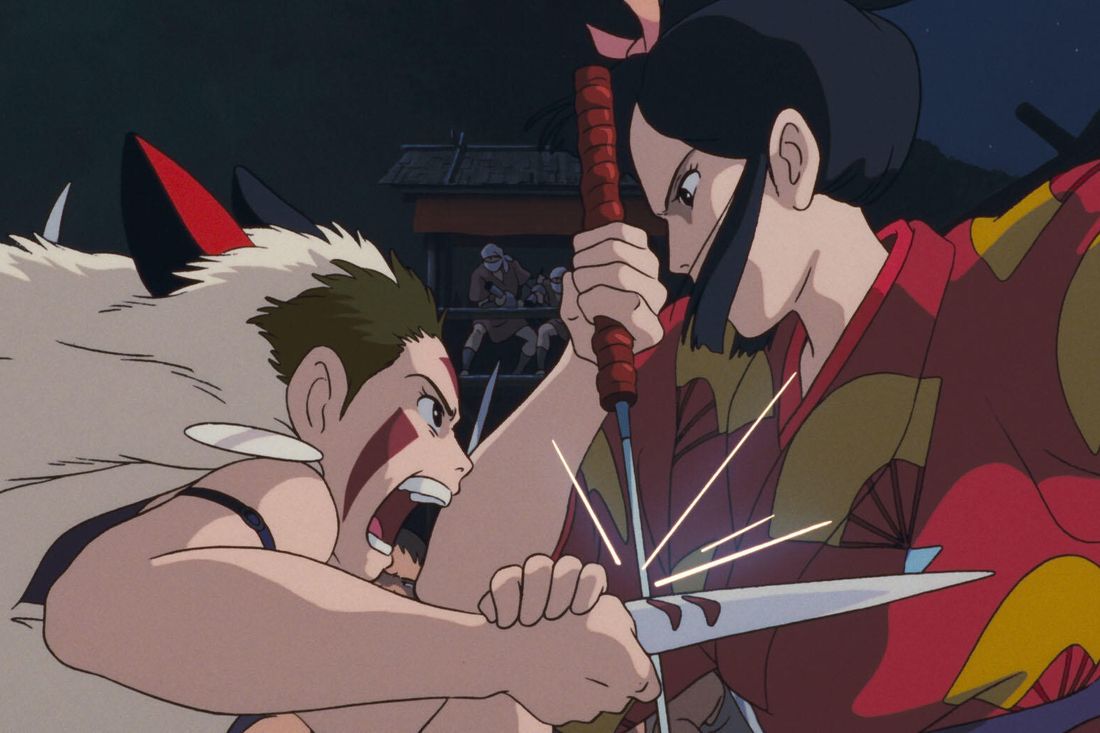

In a stark contrast, the painstakingly crafted film from Studio Ghibli, “Princess Mononoke,” showcased its most intense violence yet, but also embodied an unusually hopeful tone. The story revolves around a protagonist who finds healing by embarking on a long journey away from home and seeking to grasp difficulties that are alien to him, even as they present formidable challenges. “I am truly thankful for the time and knowledge these people shared with me,” Encinas expressed. “The time spent should have been dedicated to the movie’s production instead of educating a novice like myself. That gesture meant a great deal.

Read More

- Who Is Harley Wallace? The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Bring Her Back’s Dedication

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- Here’s Why Your Nintendo Switch 2 Display Looks So Blurry

- 100 Most-Watched TV Series of 2024-25 Across Streaming, Broadcast and Cable: ‘Squid Game’ Leads This Season’s Rankers

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- Elden Ring Nightreign Enhanced Boss Arrives in Surprise Update

- How to play Delta Force Black Hawk Down campaign solo. Single player Explained

- Jeremy Allen White Could Break 6-Year Oscars Streak With Bruce Springsteen Role

- MrBeast removes controversial AI thumbnail tool after wave of backlash

- KPop Demon Hunters: Real Ages Revealed?!

2025-03-27 21:54