“The boy was murdered, I think, by the people who were meant to love him.”

In an intriguing moment of Wes Anderson’s new movie, The Phoenician Scheme, the main character, the formidable global magnate Zsa-Zsa Korda (portrayed by Benicio del Toro), encounters a peculiar scene that resembles the afterlife. Fresh from a brush with mortality, Zsa-Zsa finds himself present at a monochrome funeral for a deceased boy, whose body is contained within a casket. Could this be someone he knew? Could it be him? Is this a dream? As he gazes upon his long-departed grandmother seated beside him, he queries her about their surroundings. However, she does not acknowledge him. Then, unexpectedly, the boy in the coffin stirs back to life — and so does Zsa-Zsa.

Upcoming film “The Phoenician Scheme,” set to debut at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, could be a comedy – possibly one of Anderson’s funniest in recent years. However, it’s the type of humor Anderson has been known for over the past decade: It blends a whimsical narrative with an underlying sense of existential despair, doom, and an intense curiosity about mortality. The protagonist, Zsa-Zsa, doesn’t just experience visions of the afterlife at funerals; throughout the movie, he frequently finds himself in the midst of some sort of celestial tribunal. Drawing inspiration from Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel and a touch of Michael Powell’s dreamy style, these black-and-white hallucinations lack any religious consistency. Each is unique, with the actors (including Bill Murray and F. Murray Abraham) donning obviously fake makeup and prosthetics. According to Anderson, “These scenes are something in Zsa-Zsa’s brain – a neurological experience he’s having. Somewhere along the line, we realize this man is being confronted so aggressively with his own death that it’s altering his perspective of the world, which he has never been receptive to. And what he learns in those moments, I suppose, he’s learning from himself.

In the portrayal by del Toro, the character Zsa-Zsa stands out with her imposing presence and shifting eyes that move effortlessly from ruthless resolve to puzzled perplexity. It’s no wonder that The Phoenician Scheme was primarily driven by the director’s intention to highlight this specific actor as the film’s lead. During the premiere of The French Dispatch at Cannes in 2021, Anderson hinted at casting del Toro as a European tycoon reminiscent of characters from 1960s Italian films. The character was then blended with various other influences, with the main source being Anderson’s late father-in-law, Fuad Malouf, who is dedicated in the film. Malouf was a Lebanese engineer known for his numerous ongoing international projects. Anderson recalls that when Malouf started showing signs of dementia, he showed his wife how his world operated by pulling out boxes filled with details about his various projects, much like a scene in The Phoenician Scheme, where after surviving an assassination attempt, Zsa-Zsa explains his business dealings to his apprentice daughter, Liesl (played by Mia Threapleton), in the hope that she will one day take over and manage it all.

Malouf might appear intimidating, yet Anderson shared that they had a good rapport. The darker and intricate traits of Zsa-Zsa’s personality – his greed, deceit, vindictiveness, paranoia, neglect of family, and careless approach to paying people as well as disregard for others’ suffering – were drawn from numerous 20th-century business figures. Among them were the notorious shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, film producer Carlo Ponti, Hungarian banker Árpád Plesch, and the Armenian fixer Calouste Gulbenkian, famously known as “Mr. Five Percent,” who facilitated Western companies in exploiting the oil-rich regions of the Middle East.

In “The Phoenician Scheme”, the character Zsa-Zsa, known for his widespread disdain but also deadpan humor, finds himself financially besieged by adversaries due to an excessive increase in the cost of a crucial bolt. This forces him to jetset around nations, renegotiating contracts with business associates, manipulating them into shouldering the increased expenses for various construction ventures. Essentially, it’s a narrative about trade disputes and economic extortion, starring a ruthless absentee father and a jaded power-seeker who thrives on exploitative deals. The film could be seen as mirroring some unsettling aspects of modern society – albeit in the unique Wes Anderson style. Interestingly, this is not the first time the movie seems to reflect contemporary concerns. According to the director, when shooting begins and historical events are drawn upon, it’s not uncommon for real-life events to parallel the storyline two weeks later. Coincidentally, during our conversation, Donald Trump announced plans to impose a 100% tariff on foreign films. When asked about this development, Anderson responds with a wry laugh, expressing his uncertainty about the potential implications of such a policy, saying “So you’ll take all the money?

Despite this, Anderson doesn’t consider his character, with its Trump-like traits, as a representation of the current president. As Anderson puts it, “I don’t believe Donald Trump has anything resembling a moral compass, whereas Zsa-Zsa, I think, does. However, Zsa-Zsa doesn’t act on this moral compass. This characteristic, in turn, might help him to discover a better side of himself throughout the story.

As a follower of Wes Anderson’s work, it’s hard not to notice the contrast between his whimsical, almost fairy-tale-like creations and the underlying darkness that permeates them. For instance, “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014) initially appears as a lively story about a clever concierge in a fictional European country, but it transforms into a dramatic exploration of fascist takeovers, complete with border closures, arbitrary arrests, and the deterioration of civil liberties. Similarly, his animated film “Isle of Dogs” (2018) is set in an imaginary Japanese city where a power-hungry mayor has imposed a ban on dogs, exiling them to a deserted island. Despite the perception that Anderson’s world is isolated, it seems he has been depicting authoritarianism long before many other artists who are often labeled as more politically engaged. In fact, as his style has grown increasingly intricate, the themes he addresses feel increasingly relevant and contemporary.

In a straightforward and engaging manner: The reason for his current topics was not driven by a pursuit of modern relevance. Instead, it represented an expansion of his perspective. As Anderson, born and raised in Houston, puts it, “Growing up, my world was quite small until I turned 20.” Later, he intentionally sought a broader viewpoint. A significant shift occurred when he moved to Paris in the mid-2000s and started a family. Watching Anderson’s films evolve over time is delightful because both he and his work have matured, transitioning from youthful, introspective coming-of-age stories where older characters’ contemplations of mortality felt like the musings of a young, thoughtful man envisioning his future, to more introspective later works, immersed in regret and a unique appreciation for life’s enigma. “When we were making Asteroid City, those questions were at the heart of the film,” he states now, referring to his 2023 movie that explores, among other things, the perplexing nature of both the universe and the human heart. “The film’s motivation was, I believe, a mystery surrounding death and creating some sense of poetry or art.

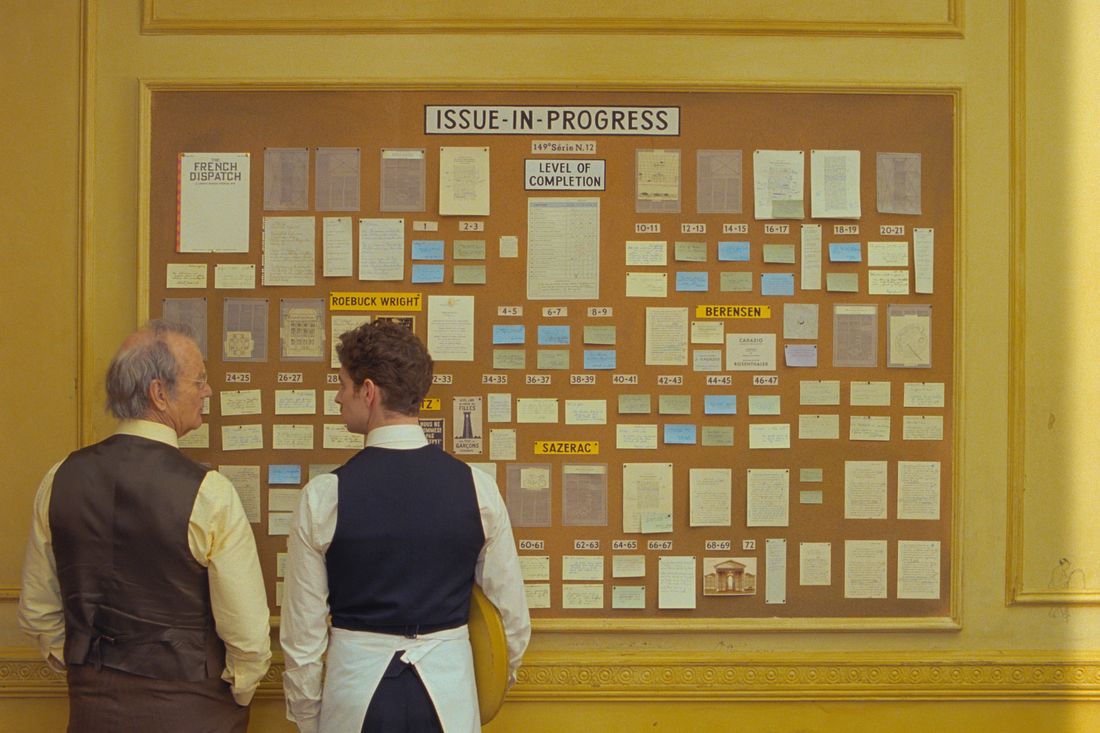

Wes Anderson’s film Asteroid City is reminiscent of the intricate mosaic of stories in The French Dispatch, focusing on journalists and their lives. Each tale within this movie showcases characters yearning to escape their circumstances, yet they are unsure how: a mentally ill artist in love who is confined, rebellious French students challenging an oppressive system, and a gay African American author, inspired by James Baldwin, living in France but exiled from his true identity, pouring all his feelings into beautifully crafted articles about food. The recurring phrase in the film — “Try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose,” spoken by a demanding magazine editor to both young and experienced writers — could be Anderson’s own motto. In his work, there is an air of deliberateness that conceals sadness, while artifice serves as a disguise for the unknown.

As Anderson matures and gains a deeper perspective, his visuals have gained an uncanny meme-like quality through their meticulous attention to detail and precision. The director’s camera movements are precise, and the compositions he creates are carefully orchestrated, blending elements of a mid-century Belgian comic book with that of a top-tier American high school science fair project. Some have questioned if he might return to a more naturalistic style at some point. However, Anderson has chosen to stick with his current approach. “It’s not always my preference,” he jokes, laughing. “Regardless of what I do, it seems like it’s my work. When it passes through me, it tends to emerge in this form. If you were sitting next to me and suggested ways to make it appear as if someone else did it, I might agree, but I think I prefer it the way it is.

In addition to the visual aspects, his work has evolved into intricately detailed structures. The film “Asteroid City” is a unique blend of movie, 1950s TV drama, play, and radio play, while a narrator constantly reminds us that everything we see is fabricated. In other words, “Asteroid City” is an imaginary production specifically designed for this broadcast, with all characters and events being fictional. On the other hand, “The French Dispatch” is presented as a collection of articles in the last issue of a fictitious magazine. Each story dives into a web of flashbacks, memories, projections, and tales-within-tales, seamlessly transitioning between color and black-and-white and varying aspect ratios. By the end of these films, both the characters and viewers experience a profound feeling of disorientation, which according to Wes Anderson, is one of his favorite aspects of cinema. He finds abstract concepts more appealing than he did when he was younger.

In my review of Asteroid City, I noted that Anderson’s intricately designed miniature worlds reflect our innate desire to structure and predict life’s unpredictable elements. Characters in the film mirror their creator by fixating on details and attempting to control their surroundings. However, this meticulousness paradoxically leads to a state of heightened confusion instead. The intertwining tales create an overwhelming sense of ambiguity, and it seems that with each new attempt, the characters find themselves more out of control. Upon discussing this idea with Anderson, he interrupts me, grinning: “Perhaps that’s why they appear so controlled,” he suggests.

Surprisingly, in the past, Wes Anderson aspired to be part of the John Cassavetes style of filmmaking – at least he attempted to. He admired unpredictability and the concept of improvisation. During his debut film, “Bottle Rocket”, he occasionally tried to encourage his actors to react to unexpected events. As he puts it, “I was aware of how William Friedkin could disrupt things on set, and something spontaneous would ensue.” For instance, for one scene, he had an actress throw a banana daiquiri in Owen Wilson’s face without warning him. “When it happened, Owen asked, ‘Why did you do that?’ To which she replied, ‘Wes told me to,'” Anderson recounts. “The spontaneous moment I was aiming to capture became entirely unattainable. And Owen was furious! He felt deceived.” It appears the idea was sound, but the method seemed incorrect for Anderson. “I had to trail Owen a quarter of a mile away while he regained his composure and I tried to explain,” Anderson added. “Then the wardrobe team approached me and said, ‘There’s no double for Owen’s shirt.’

In making “The Darjeeling Limited,” Anderson opted for a flexible approach during filming, planning as much as possible and then embracing whatever unexpected events occurred on set. He allowed for spontaneity within the structured framework, even when things veered significantly from initial plans. This unconventional method resulted in some mixed reviews upon release, but the film’s reputation has since improved over time, much like several of his other productions.

Wes Anderson attributes the creation of his first animated film, “Fantastic Mr. Fox” (2009), as a means to have more control over his shots. Since then, he’s been using animatics extensively for scene preparation. He describes them as “a storyboard cartoon version of the scenes,” often referred to simply as “the cartoon.” Initially, these were primarily shared with his production designer, Adam Stockhausen, and cinematographer Robert Yeoman (who shot all of Anderson’s live-action films until “The Phoenician Scheme,” shot by Bruno Delbonnel). Over time, some actors requested to view them. As Anderson explains, it was Willem Dafoe who started this trend, sharing the animatics with his fellow actors, encouraging them to watch and understand Anderson’s vision. However, not all actors were keen on this tool; Ralph Fiennes, for instance, showed no interest in viewing the animatics.

How does unpredictability factor into Anderson’s approach, given his highly structured and precise methodology? Might he secretly yearn for life’s spontaneity, even amidst such discipline? He emphasizes his collaborations with actors. “Working with someone like Benicio Del Toro, Timothée Chalamet, or Benedict Cumberbatch,” he notes, “these are performers who challenge you to seize the moment. They’re unpredictable, and they might take one direction, then another, and you get to explore, ‘Alright, let’s see where this leads.’ Benicio carries a certain grandeur, and sometimes you’re left guessing which facet of that grandeur will emerge.

Returning to the enigmatic figure of that deceased boy and Zsa-Zsa’s visions, as well as his celestial trials, introduces a continuous thread of dreamlike logic and mental disintegration into the intricate, mathematically dense narrative of “The Phoenician Scheme“. Though we strive to understand and classify these brief instances, they remain evasive and ephemeral. They are undoubtedly laden with symbols and concepts, but their meanings never fully coalesce—because, at heart, they are merely fleeting glimpses from a mind on the verge of collapse. As Anderson puts it, “I believe Zsa-Zsa is a control enthusiast who has lost all his grip.” In essence, he has transformed into a typical Wes Anderson character: A person whose compulsion to categorize and contain has led to existential turmoil and endless introspection.

Read More

- Who Is Harley Wallace? The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Bring Her Back’s Dedication

- Basketball Zero Boombox & Music ID Codes – Roblox

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- TikToker goes viral with world’s “most expensive” 24k gold Labubu

- 100 Most-Watched TV Series of 2024-25 Across Streaming, Broadcast and Cable: ‘Squid Game’ Leads This Season’s Rankers

- Revisiting Peter Jackson’s Epic Monster Masterpiece: King Kong’s Lasting Impact on Cinema

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- League of Legends MSI 2025: Full schedule, qualified teams & more

- How to watch the South Park Donald Trump PSA free online

- KFC launches “Kentucky Fried Comeback” with free chicken and new menu item

2025-05-17 00:55