Michelle Williams was preparing to playfully kick Rob Delaney in an intimate area. They were on a Brooklyn soundstage dressed as a typical New York apartment, both laughing and gasping audibly. Williams was wrapped up in a scarf and sweater, while Delaney wore only underwear and a unique harness he described as protective and intriguing – positioned several inches below his private parts. Despite being more exposed physically and in immediate danger, Williams had the emotionally challenging role: portraying a woman in her 40s who is only now realizing she enjoys dominating men, feeling a mix of horror, joy, and confusion about her desires as well as the idea that she can act on them. Notably, this character is near death. This story is based on real events, and it’s a comedic portrayal.

As a passionate movie reviewer, let me share my thoughts on a scene that left me both appalled and intrigued. The dialogue between Williams and Delaney was raw and intense, reminiscent of two characters locked in a heated, emotional struggle. Williams’ words were sharp as a dagger, filled with a fervor that could only be compared to a bitter, unpalatable cup of coffee.

Delaney, his eyes gleaming with an insatiable desire, seemed to invite Williams’ aggression. “Do it,” he urged, mimicking a gesture that was undeniably suggestive. His plea was simple yet intense: “Kick me in the dick. Please.” The tension in the room was palpable, as Williams’ expression morphed between disbelief, disgust, and an underlying hint of horniness.

With a swift kick, Williams connected with Delaney, the impact hard enough to be felt by both characters on-screen. Delaney, in response, let out a groan of ecstasy, while Williams screamed in pain. The scene was a testament to their acting prowess, as they managed to convey a multitude of emotions in just a few seconds.

The aftermath of the kick revealed that Williams’ character, battling stage-four breast cancer, had snapped a bone in her leg during the altercation. The scene concluded with an urgent need for medical attention, leaving the audience on the edge of their seats, eager to see how this storyline would unfold.

They repeatedly filmed the scene for nearly half a day, which felt like “numerous tough blows,” according to Delaney. “We pushed that prop to its limits.” Williams recalls the experience as “stressful.” However, she assures, “I don’t believe I caused him any harm.

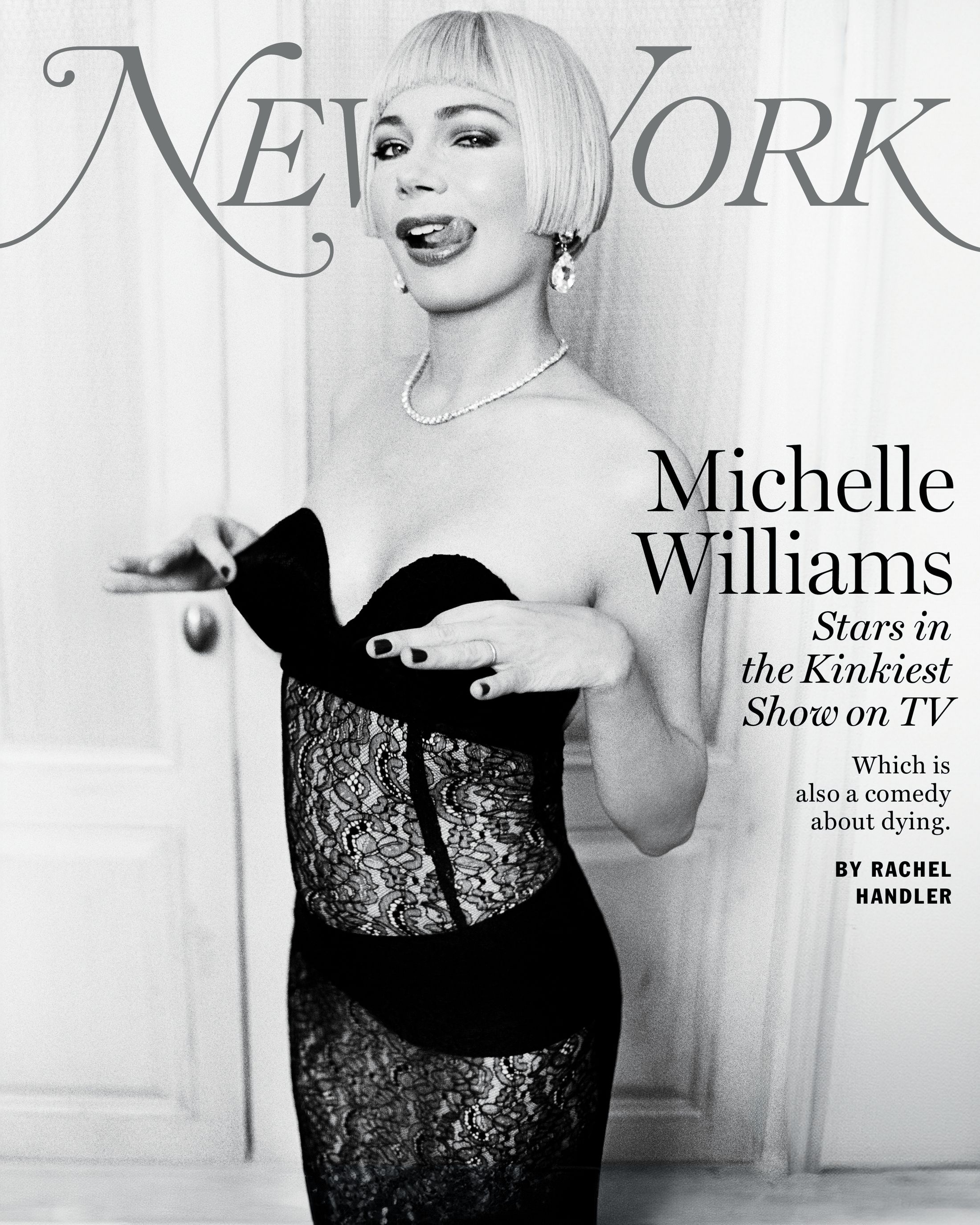

In This Issue

Michelle Williams Stars in the Kinkiest Show on TV

As a movie reviewer, I found myself utterly captivated by the eight-episode series, “Dying for Sex,” premiering on April 4th, which hails from FX and is inspired by the popular 2020 podcast of the same name. The storyline, based on the life of Molly Kochan, unfolds as she navigates her terminal illness alongside her best friend, Nikki Boyer.

From the very first episode, the series strikes a delicate balance between humor and heartbreak, leaving you both laughing and tearing up at moments. Our protagonist, Molly, played exceptionally well by Jillian Bell, is a smart, composed woman who leads a sexually repressed life. A fateful call from her doctor during a couples-therapy session sets in motion a chain of events that sees Molly leave her mediocre husband (portrayed by Jay Duplass with an air of condescension) and seek solace with Nikki (brilliantly played by Jenny Slate).

Struck by the reality of her impending death, Molly proposes to Nikki that she’d rather die in her company than within the confines of her stifling marriage. Nikki, who accepts the proposal without hesitation, becomes Molly’s companion as she embarks on a desperate quest for sexual discovery – aiming to uncover what truly excites her and if she can experience orgasm with another person before her time runs out. The series provides a raw and honest portrayal of life, love, friendship, and the human condition in the face of mortality.

Liz Meriwether and Kim Rosenstock, both co-creators and co-showrunners, first met while working in New York’s theater scene during the 2000s. They later collaborated on Meriwether’s successful sitcom “New Girl.” After COVID struck, Rosenstock began writing the pilot for “Dying for Sex.” As she reflects, it was a challenging period that forced her to contemplate her own mortality and the kind of life she desired for her daughter, as well as their relationship with their body. Since they lacked any direct narrative or tonal comparisons (though they often considered shows like “I May Destroy You” and the realistic sexual scenes in “Normal People”), they were uncertain if their work would resonate with FX executives or viewers, or even if they could produce something of quality. “We’d look at each other and ask, ‘Is this acceptable?'” Rosenstock recalls. “I think so. Let’s hope so. Let’s just keep going.’

The show kept changing from dramatic to ridiculous, funny to unrealistic, and then back again. I was curious about its tone, but no one provided an answer,” Williams jokes. It’s late February, and we’re tucked away in a corner at Inga’s Bar, one of her preferred restaurants close to her Brooklyn Heights home. Here, she chooses to meet for our talks, and although people don’t seem to recognize her, we do cross paths with Alison Roman pushing a baby stroller. Williams suggests a certain butt salve (not suitable for adults). Both Williams and Meriwether are dressed in white sweaters and jeans. They express a desire to order something called “tender lettuces,” which we all find fitting. The show, according to Meriwether, could only have been acted by Williams: “We needed the Simone Biles of acting.

At an intriguing juncture, Dying for Sex emerges. We’re dwelling under a government that openly advocates stripping autonomy, sexual or otherwise, from anyone who isn’t a white man with a receding hairline. Surprisingly, we’re encompassed by narratives, real or fictional, portraying women beyond their forties embracing sexual fulfillment: Miranda July’s All Fours, the resurgence of Nicole Kidman-led MILF stories, an influx of pro-divorce memoirs, a recent article in the New York Times Magazine about how Gen-X women are experiencing superior sexual satisfaction. On the surface, Dying for Sex might not seem as effective as it actually is, given its potential for sentimental overindulgence. However, Meriwether and Rosenstock have skillfully created something uniquely innovative. It’s subtly groundbreaking in its portrayal of heterosexual encounters; the protagonist engages in sexual activities with multiple men, predominantly without vaginal penetration, a decision that contradicts most American television shows focused on penetrative sex. It delves into kink as a means for emancipation and release, rather than as a joke or a detour to conventional sex. It doesn’t flinch from the raw realities of what transpires in a human being during the process of dying – the sounds, the slowing and distortion of time. It unabashedly embraces its quirks and theatricality, incorporating a dream-ballet sequence that includes custom puppets, one of which is a hyperrealistic penis adorned with fairy wings.

Williams expresses that the show had a profound impact on her understanding of sex, stating, “It really made me see things so clearly – it’s almost like I can’t believe I didn’t grasp this earlier.” Further elaborating, Meriwether comments, “What struck me was Molly’s decision to keep feeling, despite knowing she wouldn’t be able to for long. That choice and the pain it brings up is something I often ponder on.

Williams humorously points out that sex can be seen as a response to the concept of death, explaining it’s because it offers an intense sensation before we face nothingness. She playfully slaps the table for emphasis, then announces, “I need to head home and spend time with my husband!” she chuckles, rising from her seat.

Since starting her career at 16 when she first appeared on Dawson’s Creek, Williams has demonstrated her skills in portraying women dealing with a variety of personal and external challenges. However, she has had fewer chances to showcase her comedic talents. Notable comedic roles like the one in the underestimated ’90s Watergate satire Dick were impactful enough for Meriwether and Rosenstock to believe that Williams could manage the physical humor, rapid-fire dialogue, sudden changes in tone, and overall wit required for the show. Additionally, Williams bears a striking resemblance to Kochan, particularly during Kochan’s later years, with her short blonde hair, modelesque bone structure, and expressive eyes.

2022 saw Williams, Meriwether, and Rosenstock participating in a Zoom call. Prior to their discussion, Williams – who had just completed work on “The Fabelmans” – listened to a podcast created by Boyer and Kochan. This podcast, which detailed Kochan’s sexual experiences from her early escapades to her final months, was a journey that encompassed lighthearted banter about intimate moments, deep introspection regarding her relationships with herself, her sexuality, her mother, and her childhood trauma, all while confronting her mortality. “It shattered me,” Williams admitted about the podcast. “It’s not often one experiences such a powerful emotional response. You may like things, be impressed by things, or even be stirred by them. But to be utterly decimated by something? I can’t remember when last I had such an experience.” She wept profusely after listening to it and felt compelled to listen to it again. “What just happened to me?” she wondered. “Things don’t usually affect me like that. And I realized, ‘I need to respect the fact that something within me, which I’m not yet able to articulate, is drawn to something in this.’ ” Upon my questioning about what specifically moved her, she pondered for at least a minute. “Courage,” she finally replied. “That’s what strikes me most about it. Courage, in the face of the most challenging circumstances, to forge one’s own path.

Initially, the show was based in Los Angeles, which would have required relocation temporarily. However, Williams, having young children, prefers to limit her time away from them. “I don’t work excessively,” she explains, “but I still want to be involved.” She consented to read the upcoming scripts when they were prepared. “It wasn’t my first choice,” she confesses while picking at a piece of lettuce, “I’m a mother with multiple children. So what show am I going to do?

After becoming pregnant in 2022, she temporarily stepped away from the project. Following the birth of her third child, she also recorded an audiobook for Britney Spears’ “The Woman in Me.” During this period, Meriwether and Rosenstock collaborated with a team consisting of five women, one nonbinary individual, and one man to write additional episodes. After 20 weeks had passed, they focused on bringing her back. “She’s our ideal,” says Meriwether. “We wondered, ‘How can we get our ideal back?’

At the beginning of the following year, Meriwether encountered Williams at the 2023 Critics Choice Awards. Williams was accompanied by her closest friend, Busy Philipps, whom Meriwether was familiar with as well. Excitedly approaching them, Meriwether shared her news with Williams: “I’m relocating to New York, and I’d still be thrilled if you’d consider this project again. We have new scripts.”

As she pondered over it, Williams found herself in a contemplative state. Having taken some time off work, she was feeling restless. “I thought to myself, ‘Even though I had a baby, two and a half years is not retirement,'” she recounts. “This is becoming too much.'”

Her eldest child, Matilda, was deeply fond of the TV show New Girl, sharing a special bond with Williams (“We could say we practically raised her together,” Meriwether quips to her). Matilda was eager for Williams to take on this new opportunity to create a series revolving around themes of sex and death. “To embark on making a show about such complex topics, you truly need the encouragement of your family to say, ‘Go for it, Mom,'” Williams explains.

After about a year, Williams found herself attempting to create the illusion of six distinct orgasms during filming for the show “Dying for Sex.” On her initial day on set, she was shooting a scene where, following Molly’s departure from her husband, she checks into a hotel, receives a vibrator, and spends an entire day exploring her desires before ultimately discarding the overheated device in an ice bucket. By 5 PM, Williams had completed multiple scenes, only to be tasked with filming six separate masturbation sequences, each featuring unique, simulated orgasms. “It’s like, ‘Hooray! Let’s go!'” Williams recalls wittily. Meriwether, Rosenstock, and the intimacy coordinator were present to offer guidance. “We discussed how each orgasm should gradually intensify,” explains Meriwether. “The first should be subtle, while the last should feel like completing a marathon.” Despite her apprehension, Williams was willing to participate. “I’d joke around, saying something like, ‘Just so you know, this is Molly climaxing, not Michelle,'” says Williams. “This isn’t my genuine orgasmic expression.

In the state of Montana, where Emily grew up, her sexual education was virtually non-existent. “We were given a small bottle of Clearasil for our acne and taught how to use a condom. That’s all we got about puberty,” she recalls. “Sex can make you pregnant or potentially kill you. No one ever discussed pleasure.” Emily, who struggles with it even now, admits that she still feels a bit ashamed or unsure about discussing it. To help address this issue, Meriwether and Rosenstock invited Emily Nagoski, author of the book “Come As You Are“, to speak to their team. According to Meriwether, Nagoski’s book addresses the most common question she receives: “Is it normal?” Meriwether suggests that this deep fear and shame surrounding sexuality is widespread, particularly in America. Kochan, on the other hand, was a champion of acceptance when it comes to sex, adds Meriwether.

On the television series, Molly explores numerous ideas to achieve self-pleasure: conversing with a webcam performer, rewatching the bus chase scene from “Speed” featuring Sandra Bullock, and observing clownfish moving within a coral reef. This was inspired by an article in The New York Times that Williams read, which discussed how women can be aroused by seemingly anything. The show delves into Molly’s gradual acceptance of different forms of sex and intimacy, as well as her own eroticism, through the character of Sonya – a queer, sex-positive palliative care social worker portrayed with charm and compassion by Esco Jouléy. In a hospital conversation, Molly confesses to Sonya about her unconventional sexual experiences, such as making her neighbor masturbate in front of her while she insulted his genitals and then kicked him, expressing regret. She questions herself, saying “I don’t want to hurt people to have orgasms. What’s wrong with me?”

The show follows Molly as she experiments with various methods to reach self-pleasure, including talking to a webcam performer, rewatching the bus chase scene from “Speed” featuring Sandra Bullock, and observing clownfish in a coral reef. This is based on an article in The New York Times that Williams read, which mentioned how women can find pleasure in almost anything. The show shows Molly’s growing acceptance of different types of sex and eroticism through the character of Sonya – a queer, sex-positive palliative care social worker portrayed by Esco Jouléy with charm and empathy. In a hospital conversation, Molly shares her unconventional sexual experiences with Sonya, such as making her neighbor masturbate in front of her while she insulted his genitals and then kicked him, expressing remorse. She wonders if there is something wrong with her for needing to hurt people to have orgasms.

Sonya chuckles and shares, “You young adults today have this misconception about sex. You think it’s just about intimacy and physical pleasure because that’s what you’ve been told, right? But let me tell you, sex is more than that. It’s a feeling, an experience, a journey.” Molly listens intently. “The key to understanding your body is to pay attention to it,” Sonya continues. “It might say things you don’t want to hear or understand at first, but take the time to listen and learn from it.” Later on, Sonya introduces Molly to a BDSM-friendly gathering, where she is captivated by the diverse expressions of sexuality. Her eyes sparkle as she witnesses a live demonstration of dominance and submission. “This is what I’ve been yearning for,” Molly murmurs softly.

In creating “Dying for Sex”, Meriwether, Rosenstock, and director Shannon Murphy aimed to steer clear of the sex scenes found in films like “Fifty Shades of Grey”, where characters are frequently depicted as being manipulated or engaging in bizarre acts such as having ice cream fed into their vagina. Instead, they wanted to portray consensual BDSM practices, such as a finance broker discussing his boundaries over coffee with Molly, asking if she’s interested in cock cages. The show also explores the characters’ sexual preferences and kinks in a realistic yet humorous manner, ensuring that the jokes never belittle the individuals or their actions. Unlike other shows like “Industry” or “Sex and the City”, where acts like peeing on someone are used to mock or stigmatize characters, on “Dying for Sex”, such acts are portrayed as playful and an opportunity for sexual exploration. For instance, Molly invites a man dressed as a puppy into her bathtub and urinates on him, which is presented as a creative expression of their relationship, rather than being used to demean or pathologize the character.

A week has passed, and I find myself seated in a restaurant situated in another part of the country, this time sharing company with Nikki Boyer in person. We’re at Hugo’s in Studio City, Los Angeles – the same place where she had her last lunch with Kochan. This week coincides with the sixth anniversary of Kochan’s demise, and as Boyer reminisces about their decades-long friendship, tears flow freely, unabashedly, and spontaneously, without any apologies or acknowledgments. “Sometimes I feel like I’m speaking for her, trying to make sense of her,” she confesses. “I believe I might be the best person for this task, but still…” she adds. “Perhaps she’d say, ‘No, darling, that’s not what I meant…'” She pauses and shakes her head. “No, I think she’d respond, ‘That’s alright. That’s not exactly how I feel, but it’s okay. I love you still.'” She fiddles with a ring on her finger. “This is the ring she left for me.

In 1999, Kochan, aged 26, and Boyer, aged 24, crossed paths in an acting class in Los Angeles. Initially, they didn’t click. Kochan, a newcomer from New York, viewed acting as more of a pastime; she aspired to make her mark on the world through writing but was unsure how. Boyer, a St. Louis transplant, was outgoing, flirtatious, and keen on using the class for networking and future acting success. Boyer found Kochan quiet and intriguing, describing her as an “alien model” due to her unique, cool appearance.

Paired for a scene study, they eventually became inseparable friends, sharing long lunches, movie nights, and confiding their deepest secrets. Their friendship developed quickly, both emotionally and physically. Kochan, who later underwent a bilateral mastectomy, used Boyer’s breasts as a model for her reconstructive surgery. In the TV show Dying for Sex, a scene where Molly casually holds Nikki’s breasts while chatting in bed is said to be based on real life. During their early years of friendship, Kochan, who Boyer believes was partially supported by family funds and wasn’t working full-time, often accompanied Boyer on errands, auditions, and provided support during preparation for jobs and family airport pickups. “She was such an enthusiastic participant in life,” says Boyer, “always saying she just wanted to be with me.

In the year 2005, Kochan discovered a minor growth in her breast and consulted her gynecologist regarding it. He downplayed her concern, stating it was insignificant and that at her young age, there was no need to worry about cancer. She felt ashamed for bringing up the issue. Six years later, the lump had grown large enough for her to seek a second opinion from another doctor. By then, the cancer had metastasized from her breasts to her lymph nodes. Subsequently, she underwent chemotherapy, a double mastectomy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction, as well as hormone therapy, while attempting to maintain a semblance of normalcy in her personal life. The hormones administered to her resulted in a level of sexual desire similar to that of a teenager, but her husband found it difficult to perceive her as a sexual partner given her illness. They sought counseling and endeavored to resolve the issue. Unfortunately, in 2015, she began experiencing pain in her hip – the cancer had now spread to her bones, liver, and brain. Her doctor informed her that her days were numbered. Approximately a month afterward, she started engaging in cybersex with strangers.

Kochan purchased provocative lingerie, took explicit photos, and sent sexually explicit messages over international lines. Initially, she was unable to articulate her actions or their motivation, but they gave her a sense of purpose and satisfaction, a new self-discovery. Within a year, she had ended her marriage. “I love my husband,” she said on an early episode of the podcast Dying for Sex, “but we weren’t a good romantic fit. I couldn’t find myself in this marriage for various reasons, so I left.” Kochan soon moved her sexual explorations from the digital world to the physical realm. She was willing to try anything: tickling, foot fetishes, dominance, and visiting men for morning sex on weekdays. The sex was unlike any she had experienced before. In her posthumous memoir Screw Cancer: Becoming Whole, which Boyer self-published, she wrote about how penetrative vaginal sex, throughout her life, had been a simple means of detachment, with intimacy feeling less than making out on a couch. The medications she took for her cancer caused medical menopause and made penetrative sex unfeasible for most of her post-marriage sexual encounters. She informed Boyer about her activities early on, and Boyer was captivated and motivated. “I thought, ‘This is so exciting!'” recalled Boyer. One of her few instances of judgment involved the pre-breakfast dates: “I thought, ‘Who has sex at 9 a.m.?'” The two had always wanted to collaborate creatively, and Boyer came up with the name and concept while they were driving one afternoon near Hugo’s. “I said, ‘I believe your journey is a story, and I think it’s called Dying for Sex‘” she recalled. “So her sexual exploits became a way to update me: ‘I need to tell you what happened.’ We disguised this as ‘We’re working.’ We had a sense of urgency.

Initially, Kochan and Boyer, who had already dabbled in acting and hosting, presented the concept as a television series, but no one was interested. Television executives found it difficult to grasp or market the idea. One even suggested transforming it into a “Sex and the City”-style show with a seductive female lead. Kochan refused this proposal; she recognized that it needed to be something more profound. Eventually, they chose to record it as a podcast themselves, and in 2018, they released a ten-episode series focusing on Kochan’s daring sexual adventures.

Throughout the podcast, Kochan – a captivating, humorous individual with a knack for the absurd and dry wit – casually discusses an incident where she unintentionally hurt a man’s private parts. She also mentions consulting her physician’s assistant about whether urinating into a man could harm him due to the chemotherapy drugs she was using. However, her health issues frequently interrupt at inconvenient moments. For instance, they recorded part of episode four from the emergency room after she had been admitted for blood clots; she complains about her swollen leg. As the cancer and treatments take their toll, she recognizes that intimacy may not be as it once was. She expresses disappointment about this change, yet finds a silver lining, stating, “But maybe I’m evolving.” She openly confides in Boyer about her desire to meet someone who is genuinely interested in love, someone who wants to understand and appreciate her.

By autumn 2018, Kochan’s health began deteriorating significantly. During their last lunch at Hugo’s, Boyer remembers her as being frail and unable to keep food in her stomach. Despite this, they both believed she had several more years ahead, not months. Approximately a month later, Kochan was admitted to the hospital. Boyer took on the role of one of her full-time caregivers, performing tasks such as washing her face, massaging her legs, delivering soup, and staying by her side during bouts of pain. From the hospital, Kochan continued working on a memoir that shed light on the more troubling aspects of her life, including instances of childhood neglect and sexual abuse. These events, she claimed, led to her repression of her sexuality and disassociation from herself. The tone of this memoir contrasts sharply with the podcast – it’s raw, frequently angry, and unpolished. Boyer describes it as the hurt parts of her. He sees the podcast as the most authentic representation of her, while the portrayal of Molly in the series mirrors how Kochan wished to be perceived.

2019 found me parked alone, my car a refuge, as I grappled with the impending demise of Kochan. I was determined to share her tale before it was too late; I was willing to upload the podcast episodes myself on YouTube or seek aid from an external source. Earlier, I’d pitched the podcast idea to Hernan Lopez, then CEO of Wondery, but he hadn’t responded. Yet, I dared to try again. Little did I know, he’d missed my first email and was taken aback by the ten episodes I subsequently sent him. He visited Kochan in the hospital on Valentine’s Day, held her hand, and promised to help narrate her story. As she lay there, we began signing contracts. In her final days, Kochan was, as I describe it, “disengaging from reality.” She started experiencing hallucinations – clocks falling off walls, aliens standing behind medical staff, providing them information. “Her gaze spoke volumes,” I recall. “I saw the detachment in her eyes, the way she looked at me.” Yet, despite her fragile state, Kochan continued writing her book, and we sporadically recorded, using my phone.

During that period, Kochan handled her approaching death with a calm assurance and an awareness stemming from the manner in which she had managed her intimate relationships. She started rejecting visitors who seemed to drain her vitality. She confronted doctors who patronized or spoke to her without empathy. She carefully distributed her possessions to those she believed would value them most. According to Boyer, “She was so conscious of how she wanted to spend her final days that I couldn’t help but think, ‘I believe this is about more than just her sexual life. This seems to be about guiding her own ending and being fully present for the remaining time she had.’

listening to these accounts from that period is heart-wrenching. Kochan’s voice becomes softer, more hushed, with each breath sounding rougher. She relinquishes the need for sex. “I don’t yearn for it,” she states. “Sex can help you connect with your body or discover it, and I no longer require that connection.” Kochan passed away on March 8, 2019, at the age of 45. She bequeathed everything to Boyer: her memoir, her computer, her phone. “She told me, ‘Swear to me that you’ll publish my book. Swear to me that you’ll do whatever is necessary to get this out there.’ She deeply desired to leave a lasting impact on this world,” Boyer recalls.

In February 2020, a year post Kochan’s passing, the podcast was launched, comprising of the initial ten self-produced episodes, Boyer’s hospital recordings, excerpts from Kochan’s book, and additional research conducted by Boyer following Kochan’s demise. The podcast became an instant sensation. It reached Meriwether’s inbox that March, recommended by a producer with whom she had previously collaborated. At the time, Meriwether was engrossed in producing the Elizabeth Holmes miniseries titled “The Dropout”. However, Kochan’s tale captivated her instantly. “The podcast starts, and it feels like you’re just chilling with friends,” Meriwether says. “And by the end, you’re left wondering, How did this turn into the most profound story I’ve ever heard?” Before the final episode of the podcast was aired, Boyer met with several potential adaptors. She sought Kochan’s advice in deciding who would be suitable to narrate their shared tale. “I often spoke to her,” Boyer recalls. “Funnily enough, she always told me, ‘You’re my soul mate.’ I used to dismiss it, saying, ‘I adore you so much. No, you’re not my soul mate. Stop being strange.’ But now I think, Oh my God. She really was my soul mate.

In the television series, Jenny Slate’s character Nikki tirelessly sacrifices her personal life for Molly’s care, yet she skillfully conceals the strain this places on her. Slate’s acting talent is evident in every scene, as she portrays the complex emotions Nikki experiences: the overwhelming stress, the profound sorrow over Molly’s approaching death, the happiness derived from caring for her, the simmering anger towards the healthcare system that let Molly down, the sunny facade she maintains to make Molly feel secure and fearless. In a particularly poignant scene, after Molly suffers a near-fatal incident and requires a breathing tube, exhausted Nikki stands by Molly’s bedside, delivering a succession of monologues – Shakespearean verses, lines from Cher in “Clueless” – while Molly, speechless, simply gazes on, expressing gratitude and love through her eyes.

In late 2023, a chemistry reading opportunity came to Slate, who was eager for a project that offered both depth and scope beyond her comedic skills. With a mortgage and a young child to consider, turning down other jobs in anticipation of this role was risky. “I kept saying, ‘I want to spread my wings,'” Slate recalls. “I felt like I was only being given small tasks. I wanted to show what I’m capable of, but it’s difficult to explain without demonstrating it.” Overwhelmed with gratitude upon getting the role, she described it as “the most significant one yet.

In her portrayal of Boyer, Slate chose not to imitate her directly. She explains, “I waited until we were nearly finished before listening to the entire podcast, as I didn’t want to be preoccupied with trying to mimic her, and it seemed she didn’t place much importance on that either.” Instead, she focused on capturing the essence of the project, as Boyer and Molly share a deep spiritual connection.

When Boyer initially witnessed Slate and Williams in character on set as Molly for the first time, she expressed, “It didn’t seem like me and Molly, yet it felt strangely familiar, like me and Molly.” The transformation of Williams was particularly astonishing to observe. “I believe there was something deeply spiritual occurring because she transformed into Molly so frequently that I wondered, How could she have known how to do that with her mouth? How could she have known how to hold her shoulders that way? ” expressed Boyer.

Williams derived insights regarding Molly’s physical characteristics from pictures, the podcast, and her writings. “In essence, you can make an educated estimate about their mannerisms based on the provided information,” she explains. “She really shines through in the podcast – her timing, her way of speaking is just captivating.

On set, Williams prefers toting a personal school-like notebook with her. She refers to it as “my touchstones.” Since the film Blue Valentine, she’s been crafting character workbooks for each job, filled with thoughts, inspirations, poetry, quotes from friends, and jottings about the world she observes. The brand is always Postalco, a Japanese company, and it must have a grid pattern. When ideas seem to falter, she turns to her book in search of fresh perspectives to enliven the scene. Williams keeps the contents of her notebook private. “The personal history I bring to it, the way the script intertwines with that, and how words serve as stitches for my learning and growth” are things she guards jealously, she says. “You need to create a sanctuary within yourself. Otherwise, you won’t endure.

In 1998, Annie Leibovitz captured a striking image of Susan Sontag at Mount Sinai Hospital. Sick and dressed in a hospital gown, she gazes seductively into the camera with an intent look, her lover being the focus. Peeking out from under the covers is one of her bare legs, casually spread.

During one of their initial discussions, Williams shared an image that had left a lasting impression on him. “She’s ill and lying in a hospital bed, yet she’s being captured by the person she cherishes deeply. Her leg is exposed from the covers, and there’s an allure that’s both provocative and heartwarming. There’s so much love and desire in her gaze; she looks radiant with love,” Williams explained. “This moment has stayed with me for years, and it resurfaced during this series. Molly is required to embrace her body, flaws and all, despite her resistance. This acceptance allows her to understand and accept the ways bodies interact with people’s desires. It was a powerful message.

According to Meriwether, the portrait served as a guiding light for the series, particularly the concept that “an unwell body can still express sexuality.” She penned the episodes focusing on Molly’s demise while keeping the photograph in mind. Williams also found it significant. On set, before filming Molly’s death scene, she extended her leg from under the hospital sheets and asked Meriwether, “Are we capturing the leg?” Meriwether was taken aback. “To be immersed in all that intensity, to maintain the character while also observing from the outside,” she says, “it’s quite powerful stuff.

In the restaurant, Williams attempts to convey the emotions of the death scene, pausing frequently and sometimes speaking directly to herself. She begins by describing Molly’s courage – the way she embraced and managed her life and death – which reminded her of the first moment she felt proud and in command of her body: when she gave birth to Matilda at 25. “I was permitted to labor for 24 hours without any intervention or supervision,” she recalls, “and I had made it clear from the start that this was what I wanted. My care provider respected my wishes and helped create the experience I had asked for.

Despite reaching a high level of pain (nine out of ten on the scale), she and her doctor persisted with the natural childbirth plan. This event had a profound impact on her self-image. “At that time, witnessing my body’s ability to do something so incredible… How could I not cherish myself if I could bring this experience into existence? If I could create something so beautiful, so perfect, what could possibly be flawed in me?” she recounts. This moment marked a new beginning for her. “In that instant, I felt like I was reborn anew.” The fact that her doctor respected her decisions and let her continue despite the intense pain—giving her control—was equally empowering. “I carried this experience with me, being in control,” Williams explains. “I truly enjoyed being the leader.

In a later reflection, she drew a parallel between the act of childbirth she underwent and the death scene. As Williams puts it, “Life and death coexist in the same space, at the same time.” This experience, for her, was symbolic: when a doctor facilitates a patient’s desired exit, it reminded her of her own experience at age 25, where she deeply appreciated the care she received, which allowed her to feel fully involved in the process.

At dusk, marking both the wrap of the filming and her own dramatic scene, Williams rose from the bed in the hospital set. Stepping out into the daylight, she moved beyond the stage’s boundaries and found herself under the sun. “It’s strange to just step away from it,” she mused about her role that required pretending to die and then returning to life. “It feels like the most joyous encounter one could ever dream of.” She started to sprint. “I can still recall how my legs seemed so long,” she reminisced, flashing a smile. “I felt like a gazelle or something. As if I hadn’t known my body was capable of such movement.

Read More

- Who Is Harley Wallace? The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Bring Her Back’s Dedication

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- Here’s Why Your Nintendo Switch 2 Display Looks So Blurry

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- 100 Most-Watched TV Series of 2024-25 Across Streaming, Broadcast and Cable: ‘Squid Game’ Leads This Season’s Rankers

- Elden Ring Nightreign Enhanced Boss Arrives in Surprise Update

- How to play Delta Force Black Hawk Down campaign solo. Single player Explained

- Jeremy Allen White Could Break 6-Year Oscars Streak With Bruce Springsteen Role

- MrBeast removes controversial AI thumbnail tool after wave of backlash

- Mirren Star Legends Tier List [Global Release] (May 2025)

2025-03-24 15:25