As a seasoned journalist who has had the privilege of exploring the hallowed grounds of Disney’s Animation Research Library, I can confidently assert that the experience was nothing short of breathtaking. The anticipation leading up to our visit was palpable, and as we stepped inside, it became immediately clear that we were in the presence of something truly extraordinary.

Back in 1944, I, as an ardent Disney fan, was thrilled when they decided to bring “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” back to cinemas across the country. This iconic film had left a lasting impression during its initial release in 1937. Not only did it mark a groundbreaking technical achievement as the first full-length animated feature, but it also resonated with audiences critically and commercially.

From my perspective, the Disney Vault may appear as an elusive concept to many – a marketing ploy that stirs up frustration among some, with numerous YouTube videos expressing their discontent. However, let me assure you, Disney has skillfully maintained the illusion of the Disney Vault as a tangible yet hidden entity, similar to magical realms in Disney stories that reside more in our minds than in reality. Yet, I’ve had the privilege of experiencing it firsthand.

In the unremarkable area of Glendale, California, there stands a bland beige edifice without any identifying marks or features. The sole indication of its true identity is the extreme security measures encompassing the building. For employees of the company, access remains challenging and elusive. Contrasting the inviting glass structure housing the main studio archives nearby, which boasts ample signage and welcoming atmosphere, this location seems like an illusion or a figment of the imagination. (Note: I worked there for nearly two years yet never managed to visit.) Instead of the publicly showcased Disney Vault depicted in company documentaries, it’s this building that remains shrouded in mystery.

Upon entering the lobby, you’ll be informed that this is the sole spot in the entire complex where photography is permitted. A tall man named Tom cautions against geo-tagging your photos for good measure. Effectively, this place operates independently from the grid. It’s a hidden gem at Disney, akin to Area 51. Welcome to the Animation Research Library.

As you explore the lobby, you can almost sense the rich history. The room is adorned with relics from Disney’s past. Above your head, antique lantern-style light fixtures hang, remnants of the Walt Disney Animation Studio in Burbank before its recent renovation. In a corner, an old piano rests, once part of the studio’s “music room.” Leaning against a wall is an animation desk formerly used by Pres Romanillos, a talented animator who brought his characters to life by sketching them onto the wooden frame (He tragically passed away in 2010 at 47). This building holds a special place in Disney’s history. It was the site where beloved films like “The Little Mermaid” and “Aladdin” were created, following the animation unit’s departure from the main Disney lot and before the construction of the “hat building” nearby in Burbank. During the production of “The Lion King,” some animators even lived here when the Northridge earthquake struck. And that’s just scratching the surface – we haven’t even reached the actual vault yet.

Before entering, Tom prepares us by requesting that we hand over our pens first. He indicates a box of pencils we can use instead, but I’ve taken notes on my iPhone. Tom cautions us to keep an eye out for swinging bags or backpacks as original artwork will be showcased. Additionally: Absolutely no photography is allowed.

In terms of size, the vault is extraordinary, housing a total of twelve meticulously organized sections for various projects. It contains an impressive array of items, ranging from preliminary sketches for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to full-sized puppets from “The Nightmare Before Christmas” and “Frankenweenie.” Each room is climate-controlled, securely protected with advanced security and fire-suppression systems, and carefully cataloged. With an estimated 65 million pieces of animation artwork, this collection is the world’s largest. The vault design is reminiscent of what one might expect – rows of cabinets filled with art, which can be accessed using large turning handles. The artwork is stored in a manner that preserves its condition: horizontally for cells or production artwork and vertically for less sensitive items in accordion-style folders. Oversized pieces like large background paintings are kept in separate flat files. Entering one of these vaults feels like discovering the warehouse from “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” except instead of guarding precious historical and governmental secrets, you’re surrounded by sketches of Mulan and greeted by someone named Tom urging you to stay behind a safety line.

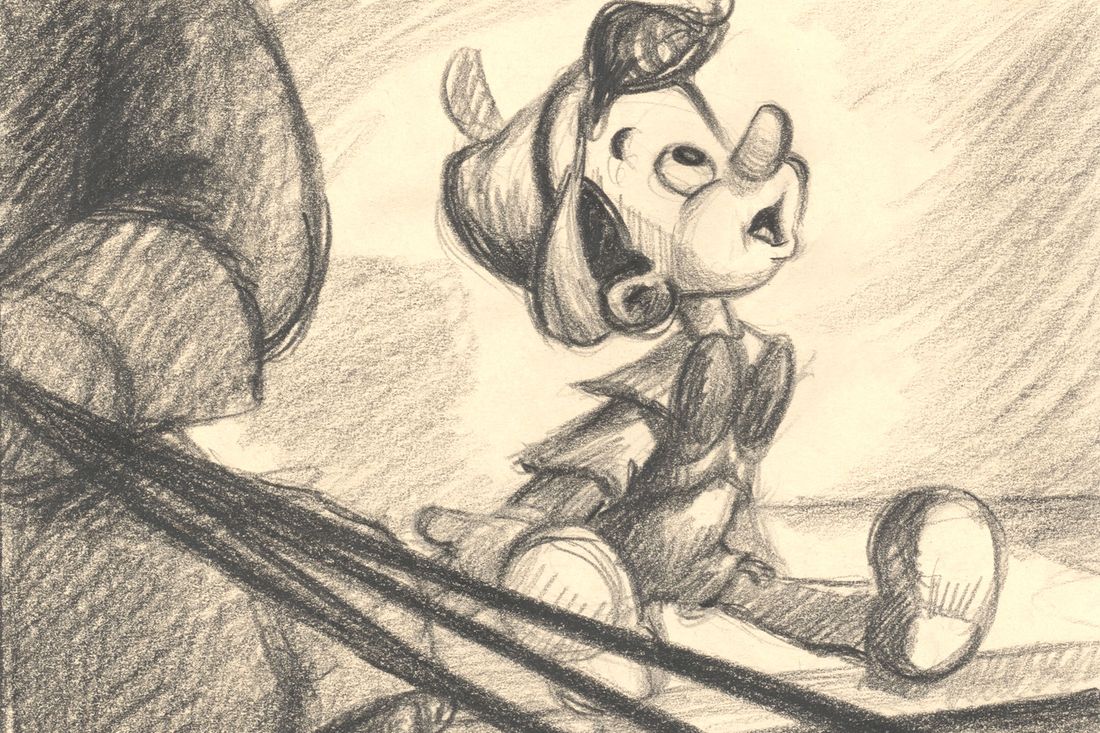

I attended the event along with a few other journalists, supposedly to mark Pinocchio’s digital rerelease from the Disney Vault. During this visit, I had an opportunity to speak with Fox Carney, who manages the Animation Research Library. He mentioned casually that their archives housed more than a million individual pieces of artwork dedicated just to Pinocchio.

I acknowledge that the library isn’t all-encompassing; it has its missing pieces, such as an estimated multitude of artworks that Walt Disney generously bestowed upon Ray Bradbury. During my conversation with Carney, he expressed his longing for one particular item – the original version of Disney’s “Pinocchio.” The production process for this film was infamously challenging (as Carney put it), with numerous animated sequences that ultimately got discarded.

Carney acknowledged that much of the art in question might no longer be in existence. Nearby was a sizable space at the back of the building, aptly named the Black Table, where items were scrutinized before being classified and documented for public or confidential purposes. It’s possible that they didn’t keep that artwork. However, we could imagine an exciting tale, reminiscent of Indiana Jones, where a storage unit in North Hollywood has been leased since 1938, preserving all the lost art. Yet, this theory veers towards fantasy.

The Vault serves dual functions beyond just storing items. Its primary role is curatorial, where art collections are prepared and disbursed for various exhibitions. These may include Disney-themed galleries in China or presentations at events like D23 Expo. Additionally, the Vault plays an educational role, with frequent inquiries from different Disney divisions seeking access to materials for their projects – such as creating new theme park attractions or merchandise related to films. For instance, a team of five archivists dedicated about a year to gathering material for the recent re-release of “Pinocchio.”

The vault can also be helpful for those writing about these animated masterworks. I spoke to J.B. Kaufman, whose book Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic, is the definitive account of the film’s production. “A lot of what I look at is the exposure sheets,” Kaufman told me. “The exposure sheets will tell you a lot of information that just isn’t available anywhere else. And when they did retake orders [an instruction to reanimate a given sequence], those are filed with the exposure sheets. I was researching the sequence where the Blue Fairy comes to Geppetto’s workshop, and there’s a scene that serves as a Rosetta stone, where they were establishing how this character was animated. There were 11 retake orders for this one scene.” Kaufman added: “That, to me, was one of the great eye-openers — to see just how meticulous they were about getting that aspect exactly right.”

The allure of delving into the Disney Vault lies in the unexpected discovery of long-forgotten treasures. “On any given day,” Carney shared with me, “you could unearth artwork that has been untouched for 20, 30, or even 40 years.”

The Animation Research Library, similar to many libraries, is transitioning into the digital era. During our tour, we entered a room where a team of technicians were meticulously working on converting vast amounts of content into a digital format. This process involves transforming “tangible items into digital data,” with benefits that are immeasurable. These aren’t just high-resolution files; they can take up to two minutes to capture and download. Every detail is captured, from minor imperfections like cigarette burns or coffee stains, to handwritten notes from the animators. For large pieces of artwork, such as those from “Sleeping Beauty,” which were shot on 70mm film and required animators to work on sheets as big as beds, a special process is used. This involves using a vacuum system to adhere the artwork to a table, which then moves like a conveyor belt, allowing it to be captured fully. Once digitized, this artwork is moved onto a system called GEMS, which can be accessed by employees of Walt Disney Animation Studios, Pixar, and Disney Toon Studio (producers of the “Planes” films). After digitization, you can view entire sequences in their rough form and zoom in to see the intricate details put into Geppetto’s workshop by background painters with stunning clarity.

The task ahead is challenging with over a million images already collected, and there’s much more to accomplish. However, the rewards on the other side will be substantial. As Carney put it, “This project requires significant resources from our company. It goes beyond just financial gains. It holds greater significance.”

The Disney Vault is a unique experience where you can revisit the past, sometimes even literally as you journey through different eras. This place not only allows us to reflect on the past but also influences the future. It’s fascinating how these pieces are discovered and debated among enthusiasts, and they continue to inspire new generations of artists and animators for years to come. However, gaining entry to the Disney Vault can be quite a challenge.

Read More

- ACT PREDICTION. ACT cryptocurrency

- PENDLE PREDICTION. PENDLE cryptocurrency

- W PREDICTION. W cryptocurrency

- How to Handle Smurfs in Valorant: A Guide from the Community

- NBA 2K25 Review: NBA 2K25 review: A small step forward but not a slam dunk

- Destiny 2: How Bungie’s Attrition Orbs Are Reshaping Weapon Builds

- Valorant Survey Insights: What Players Really Think

- Why has the smartschoolboy9 Reddit been banned?

- Unlocking Destiny 2: The Hidden Potential of Grand Overture and The Queenbreaker

- ESO Werewolf Build: The Ultimate Guide

2024-07-24 20:55