As someone who has spent countless hours immersed in the world of animation, I find myself deeply conflicted about the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the industry. Having followed the career of Shōji Kawamori for decades, I have witnessed firsthand the passion, creativity, and sheer talent that goes into each frame of his work. The stories he tells, the characters he brings to life, and the emotions he evokes are a testament to human ingenuity and artistic expression.

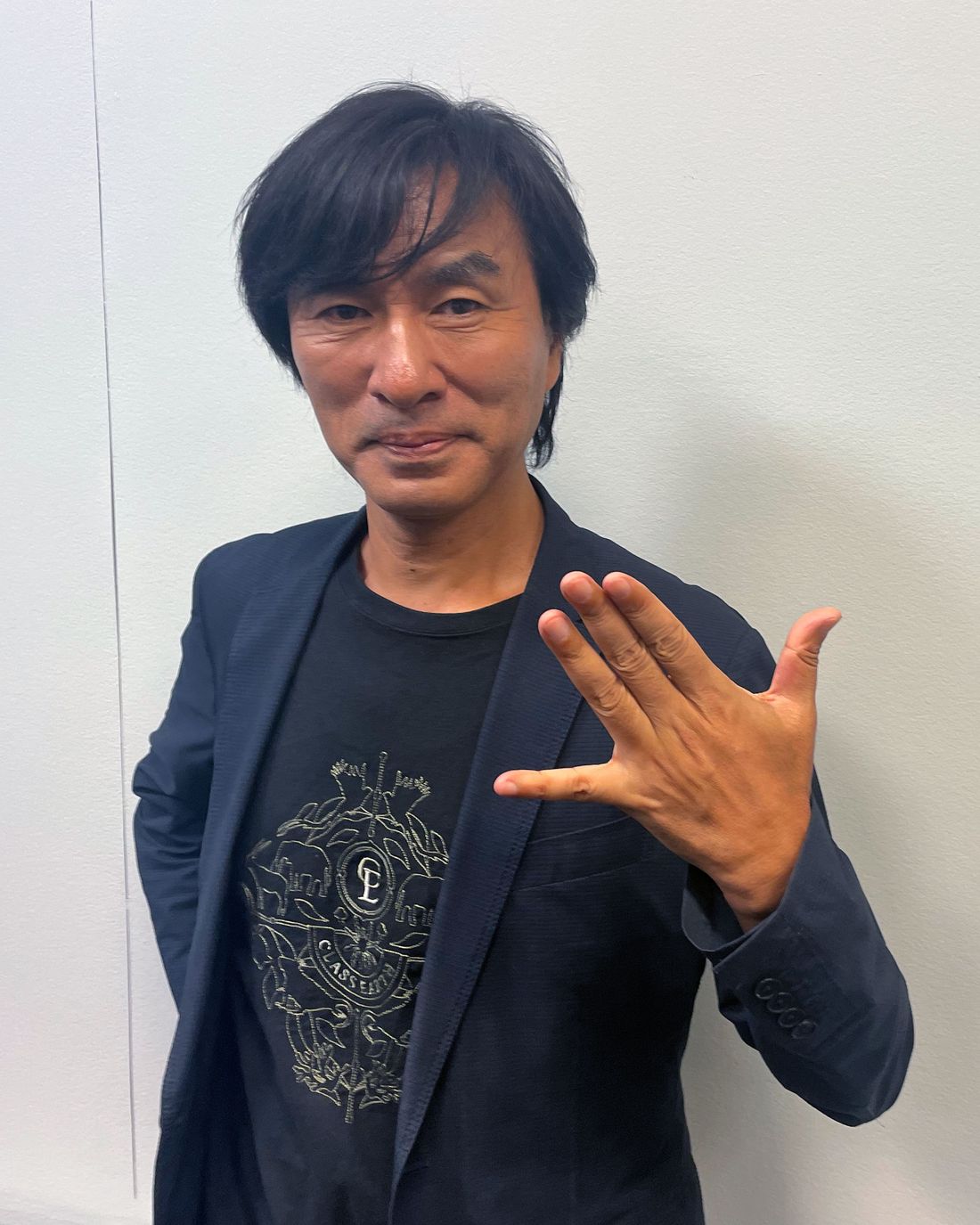

Workers affiliated with IATSE Local 839, also known as The Animation Guild, are currently in discussions about the future direction of their field. One topic under debate is the use of artificial intelligence by studios to generate visual effects previously only achievable by human artists. In Japan, a country that matches the U.S. in animation revenue and production, employees grapple with excessive work hours, low wages, and limited union representation, which could help alleviate these problems. Notably, Shoji Kawamori, a veteran animator and creator of the Macross series, has expressed openness to incorporating AI in some of his projects.

He stated during an interview at Anime NYC in late August, when he was the guest of honor, that considering cost and speed factors, AI’s use seems unavoidable. He added, disregarding any controversies, it’s simply a matter of time before it occurs.

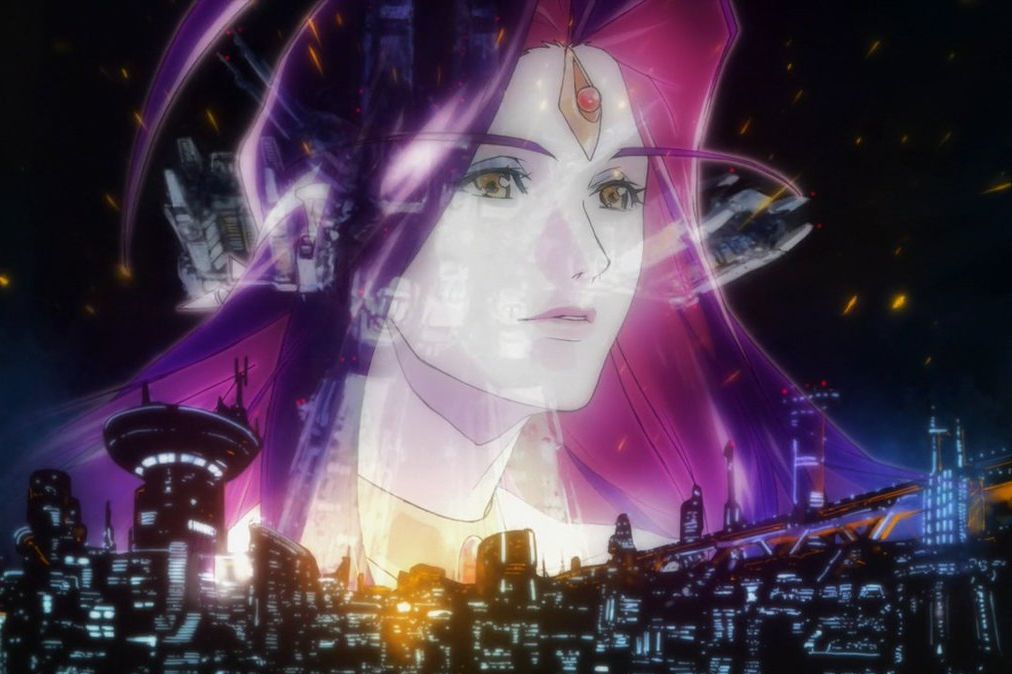

Kawamori is renowned for the precision, richness, and elegance of his mechanical design creations, a skill honed over his 47-year career. His impact on anime is extensive, with his successors frequently resembling copies: The transforming robots he designed for Diaclone were conceived before Transformers, and his series Super Dimension Fortress Macross was the basis for the first season of Robotech — sparking a fascination in the West for both Japanese action animation and transforming robots. At Anime NYC, he humorously pointed out that 1986’s Top Gun featured a heroic fighter pilot with a girlfriend who was his superior, set to an infectious soundtrack, noting that Macross had been released four years earlier. Today, he continues to guide the Macross franchise through new productions and appearances, including his most recent work in the United States.

Kawamori is not overly enthusiastic about AI. Prior to a screening of his 1995 film “Macross Plus” at the Japan Society, we had a lengthy conversation. This movie depicts an AI hologram that poses a threat to humanity and will be re-released on Blu-ray on September 30. At Anime NYC, Kawamori talked about the incredible measures he and his team take to produce their anime. His action-animation director Ichirō Itano once lost consciousness during a research flight in fighter jets, then recreated that experience for “Macross Plus“; Itano would also fire fireworks from his bicycle to gain insight into how they move in motion.

Kawamori highlights that during the ’90s, human animators sometimes struggled to keep pace with an action animator’s guidance: “My colleagues often disagreed that other animators, not Itano, could make missiles move gracefully and correctly,” he explains about Macross Plus. “However, Itano’s scenes aren’t just visually appealing; they also evoke a sense of pain when the missiles strike. The question is whether these animators truly feel the impact or if they are simply imitating him because it looks good.” According to Kawamori, the emotions and, in Itano’s case, a specific mindset that make his action scenes so powerful, cannot be fully replicated by AI, though it might one day convincingly mimic the appearance of such achievement.

As a proponent, I acknowledge that AI lacks the ability to replicate emotions authentically. However, when it comes to certain aspects of production, such as “in-betweening” – the sometimes mechanical process of inserting transition frames between keyframes in animation – I find that creativity isn’t always at its peak. While creating keyframes is undeniably a creative task, whether done by hand or with CG, the process of filling in the gaps between these keyframes, the in-betweens, can benefit greatly from the use of AI.

Junior animators, who often find themselves in the role of in-betweeners instead of lead animators working on keyframes, might express disagreement. This task, frequently referred to as the most laborious aspect of animation, has traditionally been a stepping stone for senior animators, such as Itano. However, Kawamori views it differently, particularly in terms of addressing labor shortages and financial pressures in anime production. “We’re not replacing our team members as quickly,” he notes. “There are fewer and fewer staff capable of handling this work.” He foresees its application not just for routine tasks but also in more creative processes like keyframing as an unavoidable trend. “If I find it to be highly beneficial, I might even adopt it myself,” he says.

However, an artist who’s dedicated his career to depicting human relationships with technology expresses concern that each technological advancement increases our efficiency but diminishes our creativity. “At the moment,” he muses, “I wonder: as AI continues to develop, what are the emotions we experience? And by exploring these feelings, what are we truly generating? What new ideas or creations are we actually fostering?

Kawamori knows machines can maim and divide us as often as they expand our horizons: The SDF-1 Macross ship he designed for 1982’s Macross illustrates that duality, serving simultaneously as a life raft and a war machine. Macross is ultimately a hopeful story, but if AI is as inevitable as Kawamori describes, it portends a future where animation lacks the very soul that ignited those stories — one where studios sacrifice the next generation of Itanos or Kawamoris to it.

Read More

- CKB PREDICTION. CKB cryptocurrency

- EUR INR PREDICTION

- PBX PREDICTION. PBX cryptocurrency

- IMX PREDICTION. IMX cryptocurrency

- PENDLE PREDICTION. PENDLE cryptocurrency

- USD VND PREDICTION

- TANK PREDICTION. TANK cryptocurrency

- USD DKK PREDICTION

- ICP PREDICTION. ICP cryptocurrency

- GEAR PREDICTION. GEAR cryptocurrency

2024-09-06 22:56