As a lifelong fan of the intricate and mesmerizing world of Frank Herbert’s Dune, I find myself both fascinated and frustrated with the new series, Dune: Prophecy. Having grown up devouring the original novels and being captivated by their rich tapestry of culture, religion, politics, and family dynamics, I was excited to delve deeper into this universe through a prequel series.

The issue with prequels, which are popular nowadays in Hollywood’s era of exploiting intellectual properties, lies in their assumption that our fondness for something equates to a desire to know its origins. For instance, the movie Solo: A Star Wars Story reveals how Han, the daring smuggler, got his last name, which disrupts the carefree image he portrays, answering a question that was unnecessary in the first place. The latest addition to the Dune franchise, Dune: Prophecy , also demonstrates this mistake. When a character expresses, “We are all just pieces on the board,” it becomes clear that their actions have been pre-planned from the start, making the entire production feel predictable. The lack of originality in Dune: Prophecy is both its main flaw and its defining trait.

The novel “Dune: Prophecy,” a reimagining by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson from the 2012 book “Sisterhood of Dune“, is set thousands of years before the storyline of Frank Herbert’s seminal science fiction work, “Dune“. In this novel, as well as in Denis Villeneuve’s movies “Dune” and its sequel “Dune: Part Two“, we follow Paul Atreides’ rise to power. After his family is brutally betrayed by House Harkonnen, Paul aligns with the Fremen, the native inhabitants of the arid planet Arrakis, and potentially assumes the role of a messiah. By seizing control of Arrakis’s precious spice resource and defying the Bene Gesserit order of space-witches, he challenges their centuries-long ambition to manipulate events for their benefit. In the original films, these enigmatic women serve as secondary antagonists. However, in “Prophecy“, they become complex protagonists, as the series delves into their early days and their initial power-grabbing maneuvers within the Imperium.

In the novel “Dune: Prophecy,” we find ourselves at a significant juncture in the Dune universe’s timeline, marked by humans overthrowing their enslavers – the thinking machines. This uprising led to the creation of various orders, each tasked with roles once performed by computers. The Bene Gesserit emerge as crucial figures in this universe post-rebellion. Instead of delving deeply into how this revolution reshaped life for the surviving humans, “Dune: Prophecy” adopts a more political drama reminiscent of “Game of Thrones,” where conflicts primarily revolve around power struggles (with occasional references to sandworms adding a touch of fantasy). Every now and then, there are scenes of intimacy, and the series is known for its frequent use of the spice drug.

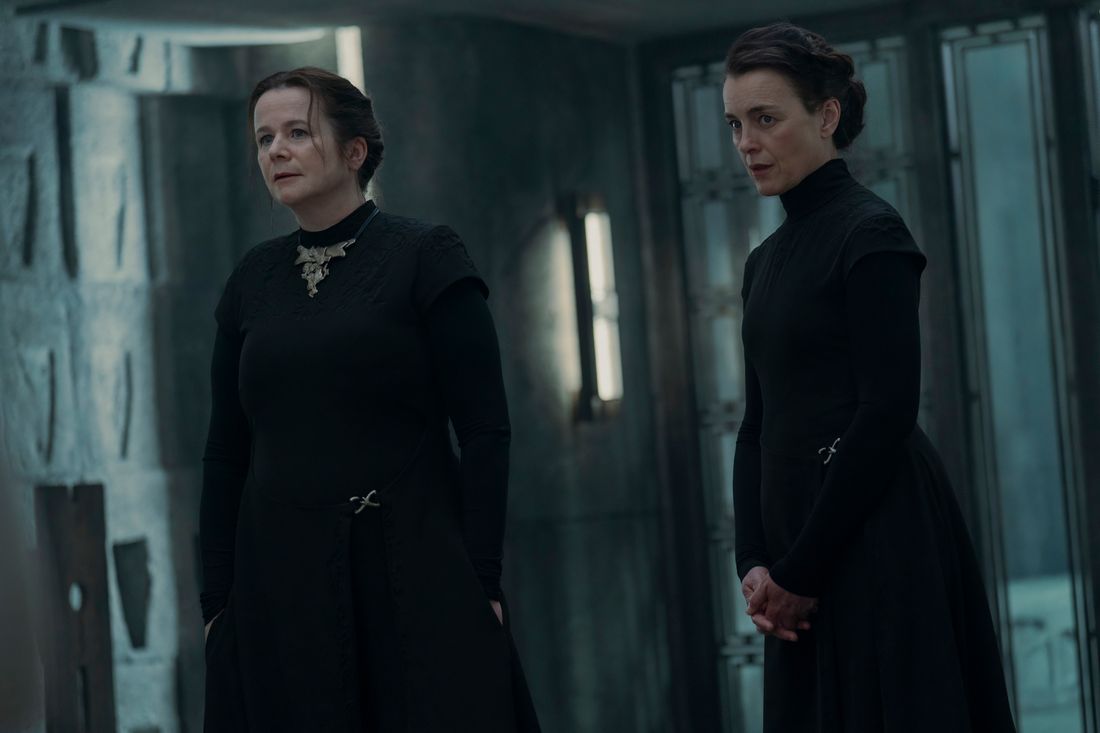

The show predominantly focuses on Reverend Mother Valya Harkonnen (portrayed by Jessica Barden as a young character and Emily Watson as an adult), portraying her journey within the Bene Gesserit order, where she eliminates rivals and eventually ascends to power. In the first four episodes, the reasons behind her actions against Emperor Corrino (played by Mark Strong, often appearing puzzled) remain obscure, but hints are dropped through her interactions with her biological sister Tula (Olivia Williams), another Reverend Mother who is more involved in teaching the Bene Gesserit acolytes than Valya. Tula, being more compassionate, also contrasts significantly from Valya. As Desmond Hart (Travis Fimmel), a war veteran with surprising abilities, begins challenging Valya’s authority, the series splits its attention between Valya’s efforts to decipher Desmond’s intentions and Tula’s guidance of the Bene Gesserit trainees, who exhibit behavior reminiscent of the girls in Le Roy.

Prophecy to delve into the Harkonnen sisters’ past, explaining how they joined the order and providing details about the Bene Gesserit’s secretive ways, such as their Voice power and talent in deceit that the series only hinted at.

Similar to Villeneuve’s adaptations of Dune, Prophecy also omits the religious and cultural aspects from Herbert’s novel that are linked to Islam and the Middle East. This results in significant character conflicts being hinted at but not fully explored. For instance, a group of Bene Gesserit sisters are referred to as “zealots,” while Desmond is portrayed as a convert whose devotion to Shai-Hulud poses a threat to Valya’s beliefs. However, without understanding how these viewpoints clash or differ from one another, the characters’ disagreements seem shallow, and their dialogue intended to express objectives feels hollow. A line such as, “The great houses are hoarding spice, forcing people to resort to violence just to survive. The only solution is to shed blood, and let me make it clear that my loyalty lies with the cause,” comes off as overtly didactic.

Prophecy introduces its characters with minimal development makes it resemble a less sophisticated young adult novel. The Bene Gesserit trainees are mainly characterized by their quarrels, and Sarah-Sofie Boussnina’s character, Princess Ynez, suffers from the series’s overly simple dialogue. When she criticizes having killers at the table, it’s unclear whether Ynez is portrayed as a brave truth-teller or a self-righteous hypocrite, given her family’s rule has led to countless deaths in the Imperium. Many characters in Dune: Prophecy feel one-dimensional because their motivations and histories are not fully explored.

The series becomes particularly captivating when it unveils fresh aspects of this world, although the presentation sometimes seems off-balance. A chilling double homicide at the start of the first episode showcases the brutality that the series typically hints at. It seems there is only one nightclub on House Corrino’s home planet Kaitain, but the scenes in that dimly lit bar offer more than just palace politics – they are filled with flirtatious and suspicious interactions. Extreme portrayals of “Agony,” a ritual where a Bene Gesserit sister transforms into a Reverend Mother by connecting with her ancestors’ consciousness, are visually unsettling. This accounts for the eerie sound effects featuring overlapping whispers and murmurs heard during scenes involving the order’s leaders. In these instances, Dune: Prophecy seems to challenge our expectations by striving to be something unexpected.

In essence, Dune: Prophecy closely follows Denis Villeneuve’s vision to such an extent that it appears as if the creators are avoiding innovation and creativity. The ominous opening, the Bene Gesserit’s costumes, and futuristic technology like vibrating shields strongly resemble the films, suggesting to fans that Dune: Prophecy will be similar to those blockbusters. However, focusing on the characters’ political machinations and concerns about their culture’s future seems pointless when the world they inhabit now looks strikingly similar to the one 10,000 years ahead. By sticking so closely to its predecessors, Dune: Prophecy weakens its central conflict, giving the implicit message that this universe will remain largely unchanged for a very long time. This predictable quality of the series seems to foreshadow Hollywood’s reluctance to challenge the prequel formula.

Read More

- SUI PREDICTION. SUI cryptocurrency

- Jennifer Love Hewitt Made a Christmas Movie to Help Process Her Grief

- LDO PREDICTION. LDO cryptocurrency

- ICP PREDICTION. ICP cryptocurrency

- Starseed Asnia Trigger Tier List & Reroll Guide

- Destiny 2: A Closer Look at the Proposed In-Game Mailbox System

- Harvey Weinstein Transferred to Hospital After ‘Alarming’ Blood Test

- FFXIV lead devs reveal secrets of Endwalker’s most iconic quest, explain favorite jobs, more

- Original Two Warcraft Games Are Getting Delisted From This Store Following Remasters’ Release

- Critics Share Concerns Over Suicide Squad’s DLC Choices: Joker, Lawless, and Mrs. Freeze

2024-11-17 21:54