Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach combines graph neural networks with frequency-domain analysis to efficiently tackle complex elasticity problems on challenging geometries.

This work presents a Multilevel Adaptive Graph Fourier Neural Solver for large-scale linear elasticity equations arising from variable-coefficient problems on unstructured grids.

Solving linear elasticity equations on complex, unstructured grids remains a persistent challenge, particularly with heterogeneous materials. This paper, ‘Vertex-based Graph Neural Solver and its Application to Linear Elasticity Equations’, introduces a novel Multilevel Adaptive Graph Fourier Neural Solver (ML-AG-FNS) that synergistically combines graph neural networks with frequency-domain correction for robust and efficient solutions. Numerical results demonstrate superior performance and scalability compared to established smoothed aggregation algebraic multigrid methods. Could this hybrid approach unlock new possibilities for tackling even more complex multi-physics simulations on increasingly refined geometries?

The Inevitable Scaling Challenge

Finite element modeling, a cornerstone of modern engineering and scientific computation, relies heavily on the efficient solution of large-scale sparse linear systems. These systems arise from discretizing complex physical problems – such as stress analysis, heat transfer, or fluid dynamics – into a network of interconnected elements. Traditional iterative methods, like the Conjugate Gradient or GMRES, serve as the primary workhorse for tackling these systems due to their ability to handle the sparsity inherent in many real-world problems. Instead of directly inverting a massive matrix, these methods progressively refine an approximate solution, minimizing computational cost and memory requirements. While direct solvers exist, their memory footprint often becomes prohibitive for truly large-scale simulations, making iterative approaches essential for pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible, particularly when simulating complex phenomena in fields like materials science and structural mechanics.

Traditional iterative methods, while foundational for solving the massive linear systems inherent in finite element modeling, face escalating challenges as simulations grow in complexity and scale. The demand for computational resources isn’t simply linear; it increases disproportionately with each added degree of freedom or refinement in the model. This is because solving these systems often requires numerous iterations, and each iteration involves matrix-vector multiplications and other operations that become prohibitively expensive for truly large-scale problems. Consequently, researchers are continually seeking more efficient algorithms and hardware solutions, including parallel computing and specialized architectures, to address this growing computational burden and enable simulations of ever more realistic and intricate phenomena.

The efficiency of iterative methods in solving the massive linear systems arising from finite element modeling is surprisingly sensitive to the quality of the initial approximation. While these methods refine an initial guess toward the true solution, a poor starting point can dramatically increase the number of iterations required for convergence, negating any algorithmic advantages. Obtaining this ‘good’ initial guess is itself a computational challenge; methods range from simple heuristics to sophisticated, computationally intensive preconditioning techniques. The cost of generating this initial approximation can, in some cases, rival or even exceed the cost of the iterative solver itself, particularly when dealing with highly complex geometries or material properties. Consequently, research increasingly focuses on developing efficient and robust strategies for generating accurate initial guesses, recognizing that the overall performance of the simulation is inextricably linked to this often-overlooked preliminary step.

Simulating the behavior of anisotropic materials-those exhibiting direction-dependent properties like differing stiffness along various axes-presents a substantial computational hurdle within the Linear Elasticity Model. Unlike isotropic materials where properties are uniform in all directions, anisotropic materials necessitate solving a much larger system of equations to accurately capture stress and strain distributions. This increased complexity stems from the need to account for the material’s response in multiple, non-equivalent directions, effectively multiplying the number of variables and computations required. Consequently, even moderately sized anisotropic structures can demand considerable memory and processing power, pushing the limits of available computational resources and necessitating advanced numerical techniques for efficient simulation. The solution of the resulting $Ax = b$ system becomes significantly more expensive, hindering detailed analyses and requiring substantial optimization to maintain feasible simulation times.

A New Iteration: The Rise of Neural Solvers

Neural solvers constitute a departure from conventional numerical methods by integrating deep learning architectures with established iterative techniques. Traditional iterative methods, while guaranteed to converge to a solution for many problems, can suffer from slow convergence rates, particularly for high-dimensional or complex systems. Neural solvers address this limitation by employing neural networks to learn and accelerate the iterative process. Specifically, these networks are trained on problem instances to predict optimal update directions or preconditioners, effectively reducing the number of iterations required to achieve a desired level of accuracy. This integration aims to retain the guaranteed convergence properties of iterative methods while significantly improving computational speed and efficiency, offering potential benefits for large-scale simulations and real-time applications.

Neural solvers utilize deep learning models to approximate the functional mapping between input problem parameters – such as boundary conditions, source terms, and domain geometry – and the corresponding solution field, effectively learning to predict solutions directly. This contrasts with traditional iterative methods which compute solutions step-by-step. By training on a dataset of problem-solution pairs, the neural network learns to generalize this mapping, enabling predictions for new, unseen problem instances. The potential for acceleration arises from the parallel processing capabilities of modern hardware and the reduced computational cost of evaluating a trained neural network compared to multiple iterations of a conventional numerical scheme. This approach allows for substantial speedups, particularly for problems where evaluating the governing equations is computationally expensive, or where many solutions for varying parameters are required.

Traditional iterative methods, such as Weighted Jacobi and Chebyshev Iteration, often require carefully tuned preconditioners and iteration weights to achieve optimal convergence rates. Neural networks offer a data-driven approach to identifying these parameters, effectively learning the optimal preconditioner and weight configurations directly from training data. This is accomplished by formulating the preconditioning or weight selection process as a function approximation problem, where the neural network is trained to map problem parameters to the corresponding optimal values. The network’s learned parameters then replace hand-tuned values, potentially leading to significant improvements in convergence speed and robustness, particularly for complex or high-dimensional problems where analytical derivation of optimal parameters is intractable. Furthermore, the learned preconditioners and weights can generalize across similar problem instances, reducing the need for re-tuning with each new problem.

Traditional numerical methods for solving problems in fields like fluid dynamics and heat transfer rely on explicitly defined algorithms and iterative processes. Data-driven approaches, however, shift this paradigm by utilizing machine learning models, specifically deep neural networks, to learn the relationship between problem inputs – such as boundary conditions and material properties – and the resulting solution field. This learning process allows the neural network to approximate the solution operator directly, potentially bypassing computationally expensive iterative steps. Instead of refining an initial guess through repeated calculations, the network predicts the solution based on learned patterns from training data, offering a fundamentally different pathway to numerical solutions and the possibility of significantly reduced computational cost and improved convergence rates.

Mapping the Function Space: Deep Operators Emerge

Neural Operators represent a shift from traditional Neural Solvers by learning the relationship between functions directly, rather than approximating solutions at discrete points. Traditional methods typically require discretization of the problem domain, transforming a continuous problem into a finite-dimensional one; Neural Operators, exemplified by architectures like DeepONet, learn a mapping $f: X \rightarrow Y$ where both $X$ and $Y$ are function spaces. This is achieved through architectures combining a branch network to encode the input function and a trunk network to decode the output function, allowing the model to generalize to unseen functions and domains without retraining on new discretizations. Consequently, Neural Operators can potentially offer higher accuracy and efficiency for solving problems defined on complex geometries or requiring high-resolution solutions.

Traditional numerical methods for solving partial differential equations (PDEs) require explicit discretization of the domain into a mesh or grid, which introduces limitations in resolution and can be computationally expensive. Neural operator-based approaches, however, circumvent this requirement by learning the solution operator directly in function space. This allows for solutions to be approximated at any point within the domain without being constrained by a predefined grid, offering increased flexibility, particularly for problems with complex geometries or moving boundaries. Furthermore, the continuous nature of the learned operator can potentially yield higher accuracy compared to discrete methods, as it avoids discretization errors inherent in finite difference, finite element, or spectral methods. The accuracy is dependent on the training data and the capacity of the neural network used to represent the operator.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) improve the accuracy and reliability of neural operator solutions by integrating the underlying physical laws directly into the training process. This is achieved by adding terms to the loss function that represent the residual of the governing equation – for example, the PDE being solved. Specifically, the loss function incorporates not only the difference between the network’s prediction and known data, but also a measure of how well the network satisfies the $PDE$ itself. By minimizing this combined loss, the network is incentivized to produce solutions that are consistent with both the observed data and the established physics, leading to more physically plausible and generalizable results, even with limited training data.

Deep Operator architectures demonstrate applicability across a broad spectrum of computational problems. Solutions extend beyond simple linear systems, such as those encountered in basic heat transfer or diffusion equations, to encompass highly complex nonlinear simulations. These include fluid dynamics governed by the Navier-Stokes equations, turbulent flow modeling, and even more intricate scenarios like multi-phase flow or reaction-diffusion systems. The ability to learn the operator directly, rather than relying on traditional discretization methods, allows for effective handling of problems with irregular geometries, high dimensionality, and complex boundary conditions, without the computational expense typically associated with fine-grained mesh generation or finite element analysis. This versatility makes them suitable for diverse applications including materials science, climate modeling, and computational biology.

Decomposition and Synergy: A Path to Scalability

The fusion of neural solvers with established numerical techniques, such as Domain Decomposition Methods, represents a significant advancement in computational efficiency and scalability. This approach strategically divides a large, complex problem into smaller, independent subproblems that can be solved concurrently, dramatically reducing overall computation time. By integrating the parallel processing capabilities of Domain Decomposition with the function approximation strengths of neural networks, researchers are achieving performance gains previously unattainable with traditional methods. The resulting hybrid systems not only accelerate simulations but also demonstrate improved handling of intricate material properties and geometries, paving the way for more realistic and detailed modeling across diverse scientific and engineering disciplines. This synergistic combination unlocks the potential to tackle increasingly large and complex problems, pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible.

Domain Decomposition represents a powerful strategy for tackling computationally intensive problems by dividing a large, complex task into numerous smaller, independent subproblems. This partitioning allows each subproblem to be solved concurrently, often leveraging parallel computing architectures to significantly reduce overall simulation time. The technique is particularly effective when dealing with problems exhibiting localized behavior, as the solutions within each subdomain have minimal impact on others. By strategically dividing the domain – whether spatial, temporal, or otherwise – and defining interfaces between subdomains, researchers can distribute the computational workload and achieve substantial gains in efficiency.

The successful implementation of Domain Decomposition hinges on carefully defined transmission conditions at the boundaries between subdomains. These conditions, which specify how variables like displacement or temperature should relate across interfaces, are crucial for ensuring that the solutions computed for each subdomain seamlessly integrate to form a globally consistent solution. Incorrectly specified transmission conditions can introduce artificial discontinuities and inaccuracies, effectively negating the benefits of parallelization. Sophisticated techniques, including iterative enforcement of continuity and the use of overlapping subdomains, are often employed to derive robust transmission conditions suitable for complex geometries and material properties. The precision with which these interfacial relationships are modeled directly impacts the overall accuracy and efficiency of the decomposed simulation, making their design a central challenge in the field.

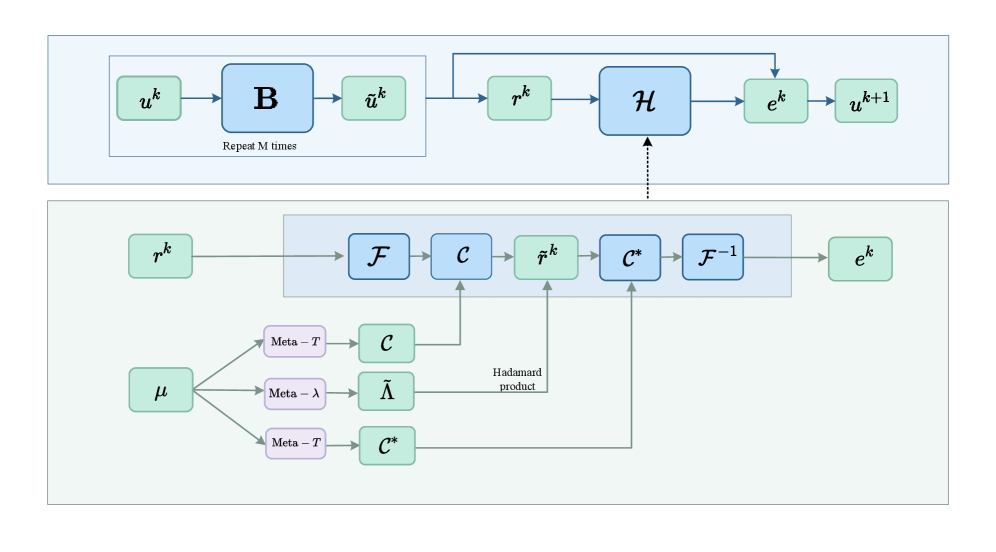

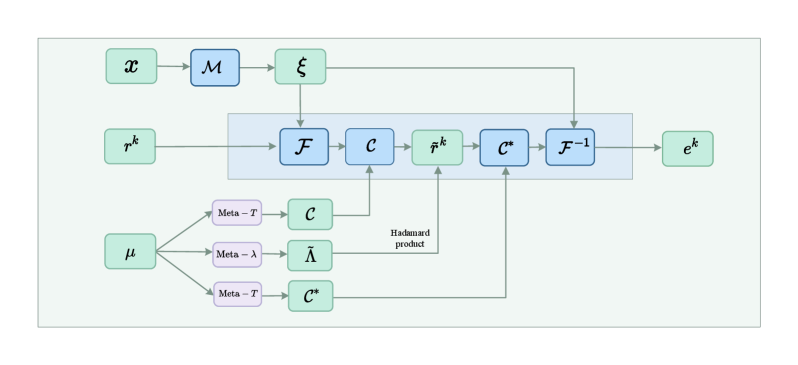

A novel computational strategy combines the established rigor of traditional numerical methods with the adaptive learning capabilities of neural networks, resulting in a powerful approach to complex simulations. The Multilevel Adaptive Graph Fourier Neural Solver (ML-AG-FNS) presented achieves superior performance compared to Smoothed Aggregation Algebraic Multigrid (SA-AMG) solvers, especially when applied to materials exhibiting anisotropy – direction-dependent properties. Benchmarking demonstrates the ML-AG-FNS’s effectiveness on problems scaled up to 11,055 degrees of freedom, suggesting its potential for tackling increasingly intricate simulations previously limited by computational cost or convergence issues. This synergistic combination allows for both the accuracy of physics-based modeling and the efficiency gained through machine learning’s ability to generalize and accelerate calculations.

The pursuit of efficient solvers for complex systems, as demonstrated by this work on the Multilevel Adaptive Graph Fourier Neural Solver, echoes a fundamental principle of enduring structures. The presented method, blending graph neural networks with frequency-domain correction, represents an attempt to refine existing approaches rather than discard them entirely. As Isaac Newton observed, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” This ML-AG-FNS builds upon established numerical techniques, iteratively improving performance for large-scale linear elasticity problems. Each refinement, each version of the solver, is a testament to the ongoing effort to mitigate decay and extend the lifespan of these critical computational tools, much like preserving the integrity of any system over time.

What Lies Ahead?

The presented Multilevel Adaptive Graph Fourier Neural Solver, while demonstrating a reprieve from the computational demands of variable-coefficient linear elasticity, merely shifts the locus of decay. Traditional iterative methods succumb to the accumulation of error with each cycle; this neural approach introduces a different form of technical debt – the fragility inherent in learned representations. The solver functions as a temporary stabilization against entropy, a rare phase of temporal harmony before the inevitable drift toward generalization error.

Future work will likely grapple not with speed alone, but with resilience. The performance gains are predicated on the quality of training data; a shift in material properties, or a move to genuinely chaotic boundary conditions, will test the limits of its adaptability. The field must consider methods for continual learning, allowing the network to gracefully accommodate the unforeseen, rather than requiring complete retraining.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether this approach solves the equations, but how elegantly it postpones the inevitable degradation of accuracy. The true metric isn’t uptime, but the rate of decay, and the cost of intervention when the learned structure can no longer withstand the pressures of the system it models. The pursuit of efficiency is, after all, simply a negotiation with time itself.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.21491.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- EUR INR PREDICTION

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- Heated Rivalry Adapts the Book’s Sex Scenes Beat by Beat

2025-11-29 23:07