A scene in the 1975 thriller *Three Days of the Condor* perfectly illustrates Robert Redford’s star power. In the film, Redford plays Joe Turner, an intellectual CIA analyst who returns from lunch to find his entire office staff murdered. He’s forced to go into hiding and enlists the help of a photographer, Kathy Hale (Faye Dunaway), using her apartment as a temporary safe haven. The tension escalates when the doorbell rings – it’s a mail carrier with a package requiring her signature.

Kathy was showering when the doorbell rang. Joe, in the kitchen, saw the postman through the front window. He told the carrier Kathy wasn’t home and asked him to leave the package on the porch. When the postman asked for a signature, Joe went outside. The postman’s pen didn’t work, so Joe went back inside to find another one. A quick glance at the man’s shoes – tan suede with racing stripes, a style postmen didn’t wear in the 70s – saved Joe’s life. As the camera focuses on the man, we see Joe quickly realize something is terribly wrong. The scene cuts to the man pulling a machine gun from his bag, followed by Joe throwing a pot of hot coffee at him, starting a violent fight that destroys the kitchen. Despite the speed of the action, the actor conveys the shift in Joe’s understanding – from a vague unease to the realization that this isn’t a postman, and he’s in danger – in just three seconds and four steps.

Robert Redford, who passed away yesterday at age 89 at his home in Provo, Utah, was a remarkable figure known for many things. Beyond his acting career, he established the Sundance Institute and its famous festival to support independent filmmakers. He created Sundance because he remembered the difficulties he faced early in his career, while making his first film as a star and producer, the ski drama *Downhill Racer*. Redford went on to direct eight films, with his first, *Ordinary People* – a critically acclaimed drama about a family dealing with grief – winning multiple Oscars. He also directed two other notable films exploring similar themes of loss and repression: *A River Runs Through It*, featuring Brad Pitt, and *The Horse Whisperer*. He tackled ethical dilemmas in *Quiz Show*, a film about a 1950s game show scandal, a story that resonated with him as a young theater student in New York. As he told the Los Angeles Times, the film explores how much of life is, in itself, a performance.

Redford was more than just a pretty face. He was a true all-rounder – a book lover, a passionate activist who championed Native American rights and environmental causes, and a skilled athlete excelling in numerous sports. He drew on these diverse experiences to enrich his acting and guide his direction of other actors. While naturally handsome, his multifaceted personality allowed him to be a versatile performer, preventing him from being defined solely by his looks.

Robert Redford captivated audiences with his natural charisma and understated grace. He was incredibly believable in a wide range of roles, portraying everything from a thoughtful rancher and skilled skier to a determined mountain man, a decorated war veteran, and even a tech-savvy hacker. He convincingly played characters facing extreme challenges – surviving shipwrecks, seeking revenge, and navigating complex moral landscapes – as well as more playful roles like a cool thief and a powerful comic-book villain.

As a huge fan, I always loved how Robert Redford blossomed later in his career. William Goldman, who wrote some of his best films, pointed out that Redford, like Clint Eastwood, didn’t become a star right away – Redford was already in his thirties when he really hit it big. He’d done some good work early on, but it was *Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid* that truly made him a household name. That film, with Paul Newman, basically invented the modern buddy movie. Redford played the Kid, this incredibly skilled gunslinger with a bit of a temper, and it was a perfect role for him – a quiet, almost reluctant hero. There’s this one scene that still blows me away. The Kid is accused of cheating at poker, and the director, George Roy Hill, just *holds* the camera on Redford’s face for a full minute! It’s amazing because studios wouldn’t let that happen now, even then. Redford barely looks at the guy accusing him, instead focusing on his gun, like a coiled snake. You think the situation is defused when he starts to leave, but then he whirls around, shoots the gun right out of the man’s holster, and sends it skittering across the floor. It’s just brilliant.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=watch?v=77juS9kSOLI

1969 was a breakthrough year for Robert Redford. In addition to the success of *Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid*, he appeared in the historical film *Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here*. He also proved his talent behind the camera with *Downhill Racer*, a film he helped produce, bringing together director Michael Ritchie and writer James Salter. He even did much of the skiing himself, filming on location with the U.S. Olympic ski team. While *Downhill Racer* appealed mostly to fans of art films, it demonstrated Redford’s ability to lead a movie and his dedication to filmmaking. *Butch Cassidy* instantly made him a bankable star – a simple “yes” from him could get a film greenlit. However, getting that “yes” wasn’t always easy. He gained a reputation for being demanding, often requiring years of rewrites and recasting from directors and writers. Despite this, people were eager to work with him because he understood what audiences wanted to see, and he consistently delivered while also adding unexpected depth to his roles. He began carefully crafting his on-screen image early on, avoiding the roles of tragic figures and losers that were popular with other actors of the time. The 1970 comedy *Little Fauss and Big Halsy* was the last time he played a flawed character – a womanizing dirt bike racer who gets disqualified for drinking. He took the role to fulfill a contractual obligation with Paramount, after they sued him for trying to break a three-picture deal.

Robert Redford often portrayed characters who were driven, proud, stubborn, or emotionally distant – but rarely someone simply inept. This tendency was evident throughout his career. A well-known story involves director Mike Nichols interviewing Redford around 1966 for the role of Ben Braddock in *The Graduate*, a disheartened and somewhat pathetic character having an affair with a neighbor’s mother. After a short time with Redford, Nichols confessed he couldn’t imagine him convincingly portraying a “loser.” Redford protested that he could, but Nichols pressed further, asking if he’d ever been rejected by a girl. Redford seemed genuinely confused by the question, asking for clarification.

Robert Redford reunited with Paul Newman for the 1973 film *The Sting*, a clever caper set during the Great Depression. It was the second highest-grossing film of the year, winning seven Academy Awards and earning Redford his only Best Actor nomination for his portrayal of the quick-witted con man, Johnny Hooker. Though he didn’t win – the award went to Jack Lemmon for *Save the Tiger* – it was a significant honor, especially considering he was up against strong competition like Al Pacino (*Serpico*), Marlon Brando (*Last Tango in Paris*), and Jack Nicholson (*The Last Detail*). Interestingly, Lemmon, known for comedy, delivered a surprisingly dark performance, while Redford’s earlier roles in romantic comedies had led some to compare him to Lemmon.

*The Sting* showcased Redford’s action hero persona with a stylish period makeover, thanks to costume designer Edith Head. His dazzling clothes, including a striking plum suit and loud two-tone shoes, even added a musical quality to the film. The movie cleverly presented the con as a complex performance, complete with scripted lines and detailed preparation, making it a film about both watching and being watched – a common theme in Redford’s work.

It also marked a shift in their partnership, with Redford taking the lead. Newman’s role as the alcoholic con man Henry Gondorff was more of a supporting one, given to him as a favor after he helped launch Redford’s career. Ultimately, *The Sting* was a timeless and highly enjoyable film that solidified Redford’s status as a major movie star.

Robert Redford first demonstrated his acting range in the 1972 film *Jeremiah Johnson*, which was far more gritty and complex than the popular image of him as a bearded, approving figure suggests. The film was directed by Sydney Pollack, who collaborated with Redford on seven films over two decades, beginning with *This Property Is Condemned* and ending with the 1990 film *Havana*, a take on *Casablanca* with Redford playing a role similar to Humphrey Bogart’s. The Redford-Pollack partnership was remarkably consistent, rivaled only by the actor-director duo of Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese, whose *Raging Bull* narrowly lost the Best Picture and Director Oscars to *Ordinary People* in 1980. (Many consider this a major upset, but Scorsese has always praised Redford’s filmmaking.) Redford even directed Scorsese in what is considered one of his finest performances, as the subtly threatening face of Geritol in *Quiz Show*. Both Redford and Pollack transitioned to producing and directing after starting as actors, and they possessed a stronger visual sense than many others who made the same switch. Redford, in particular, had studied painting earlier in his life, which likely contributed to his eye for composition.

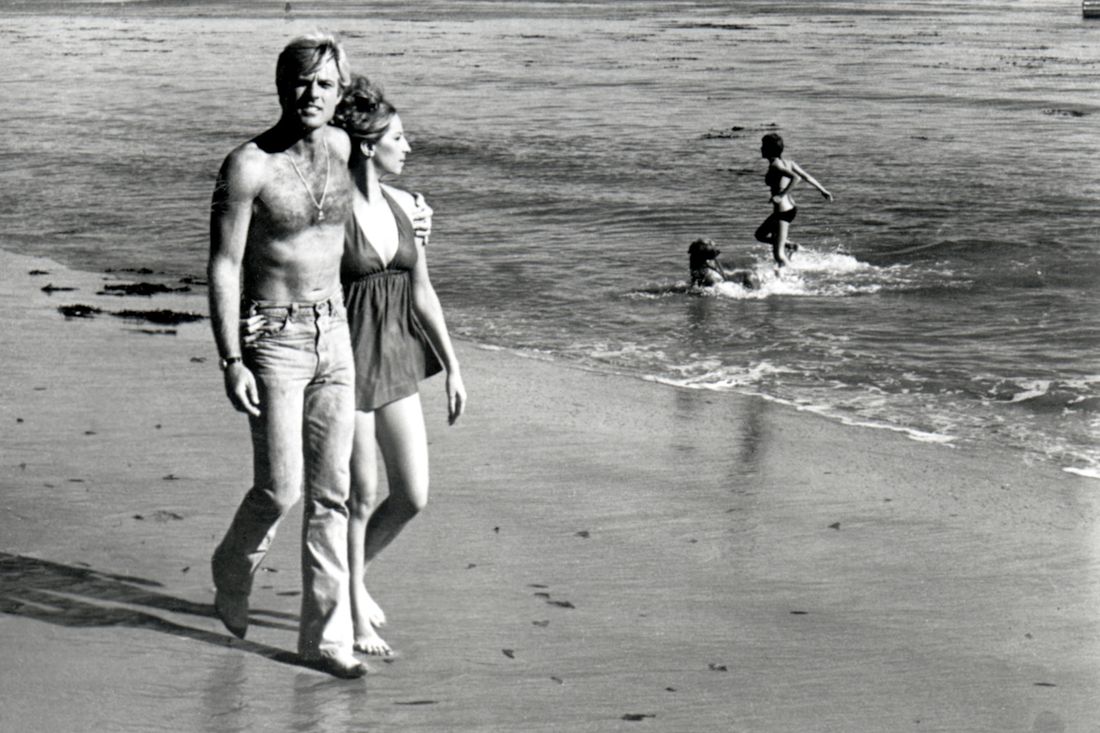

Sydney Pollack’s 1973 film, *The Way We Were*, was a massive hit, a romantic story set against a historical backdrop. Barbra Streisand played Katie Morosky, a fiery and politically engaged woman, while Robert Redford portrayed Hubbell Gardiner, a more reserved and traditional man. Their love story was ultimately torn apart by their differing political views. Like many of Redford’s romances, the film centers on the female lead. Redford’s role was largely to match Streisand’s charisma, show adoration for her character, and remain sympathetic despite his character’s conservative stance – and he achieved all of this effortlessly. He elevates the entire film by genuinely listening to his fellow actors instead of simply waiting for his turn to speak. Epic, often tragic, love stories became a signature of Redford’s work, continuing even in one of his final roles, 2017’s *Old Souls at Night*.

Robert Redford’s biggest flop of the 1970s was also the last time he played a character allowed to completely fail. The 1975 film, *The Great Waldo Pepper*, a collaboration with Goldman and Hill, featured Redford as a World War I veteran turned stunt pilot who claimed to be second only to the best. Redford believed the film’s poor reception stemmed from a shocking scene where his character convinces a woman (Susan Sarandon) to perform a wing-walking stunt, only to watch her fall to her death. Even Goldman admitted this scene, while a bold move, lost the audience who expected Redford to succeed. *Waldo Pepper* marked the final project Redford would do with Hill and Goldman. The film’s failure deeply affected Redford, making him hesitant to risk alienating audiences by portraying a character who might lose their support.

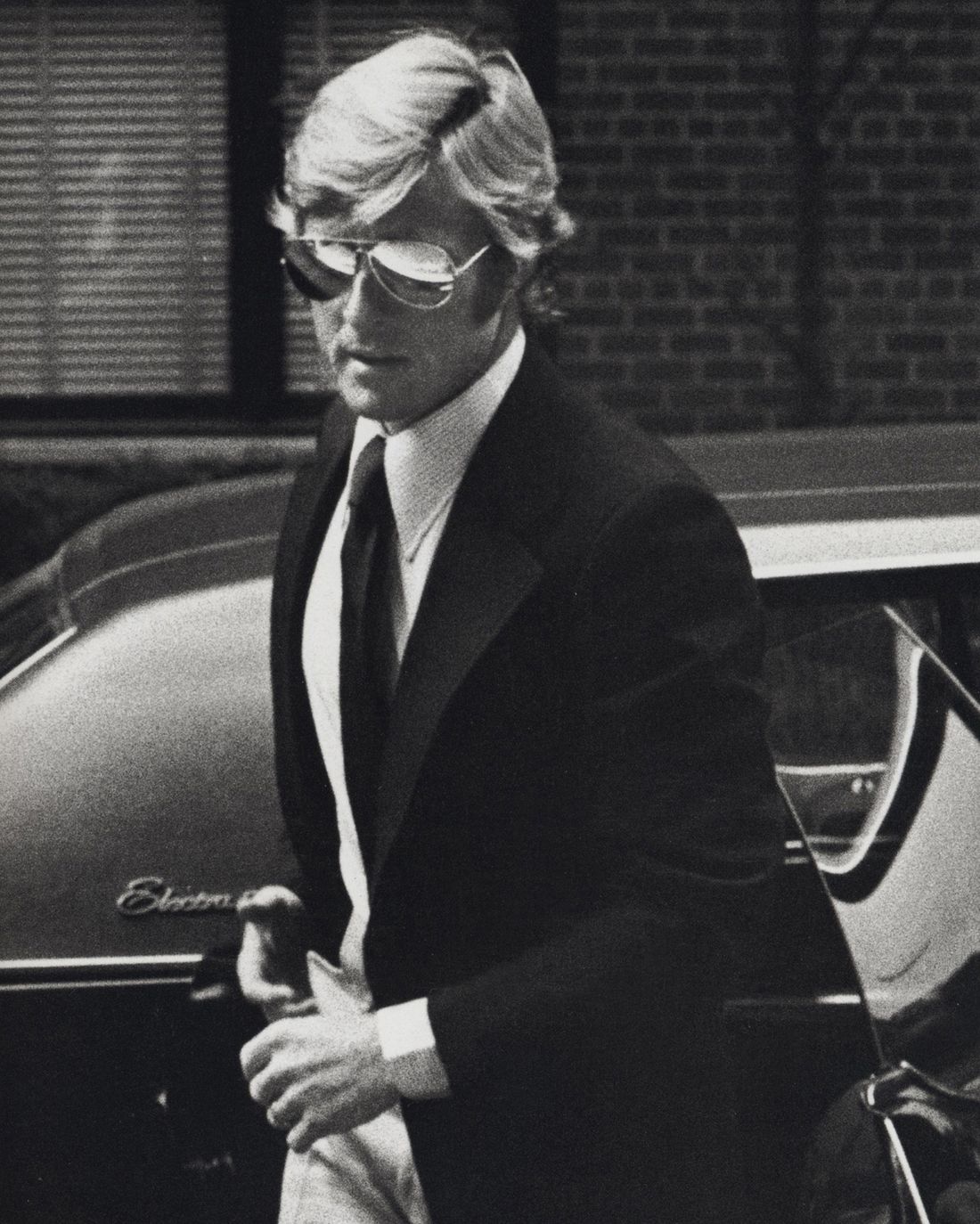

Redford followed up his directorial debut with the critically acclaimed 1976 thriller, *All the President’s Men*. He starred alongside Dustin Hoffman, playing Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward in the film about the Watergate scandal. Redford secured the rights to the reporters’ unfinished manuscript and guided the script’s development, encouraging a focus on the investigative process and the dynamic between Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The film wouldn’t have been made without Redford using his star power to get it financed – it was a story about reporters working the phones, unfolding against the backdrop of a major political event. Redford brought nuance, suspense, and wit to the scenes, and his portrayal of Woodward served as a guiding force for the entire production.

Robert Redford reached the peak of his career in 1979 with three major accomplishments: directing *Ordinary People*, founding the Sundance Institute, and starring alongside Jane Fonda again in *The Electric Horseman*, a film he co-produced with Sydney Pollack. In *The Electric Horseman*, Redford played a former rodeo star turned advertising spokesperson who goes on the run to protect an abused horse. During the 1980s, Redford shifted his focus, prioritizing activism – particularly for Native American rights and environmental causes – and his leadership of Sundance, even though he continued to act and direct. He later expressed to friends and film historian Peter Biskind that he felt his celebrity status sometimes overshadowed Sundance and became a hindrance. He also wanted to make more films, noting he’d been very productive in the 1970s but less so in the 1980s. Despite making fewer films, Redford had successes in the 80s, most notably *Out of Africa*, a sweeping romantic drama set in Kenya co-starring Meryl Streep. The film, also directed by Pollack, was a critical and commercial hit, winning seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, even with its lengthy three-hour runtime.

Robert Redford’s performance in *Out of Africa* was critically panned, and rightly so. The role didn’t suit his intelligent presence, and he began a period of taking parts that relied on his fame rather than showcasing his acting ability. He seemed hesitant to portray vulnerability or acknowledge the effects of aging. This is particularly evident in *The Natural* (1984), where his character’s comeback story feels genuine in everyday scenes, but the film avoids the darker themes of the original novel in favor of a feel-good ending, and relies heavily on flattering lighting to mask Redford’s age. The more complex or unusual the character, the less well-suited Redford seemed to be. A low point was likely *Indecent Proposal*, where he played a wealthy man who offers Demi Moore’s husband a million dollars to allow her to spend a night with him, and continues to interfere with their lives. While the film’s premise was shallow, Redford’s established image as a man of integrity made the role particularly jarring and difficult to accept.

Redford found a new footing in the 1990s, with one of his most memorable roles being surprisingly different from his usual characters. In the film *Sneakers*, he played Martin Bishop, a cybersecurity expert-essentially a high-tech James Bond. This clever caper featured a strong cast including Sidney Poitier, Ben Kingsley, and River Phoenix, and allowed Redford to bounce off the witty dialogue. The movie cleverly played against his established image by casting him as a brilliant, daring character who struggled with emotions and cracked under pressure. One standout scene has Martin bluffing his way through a situation, repeating information fed to him through an earpiece – a nod to *Cyrano de Bergerac* that showcased Redford’s unexpected ability to play nervous and self-deprecating. Even better is a satisfying moment near the end where Martin finally gets the upper hand on an attacker who’s repeatedly tried to kill him. He hesitates, seemingly realizing this is where a typical hero would deliver a cool one-liner, but he can’t think of anything to say, so he simply grunts in frustration and incapacitates the attacker with his gun.

In many of Redford’s later films, he seemed to play variations of the same character: a supremely capable, attractive, and morally upright man. A prime example is *The Last Castle*, where he’s portrayed as a blend of Rambo, the idealistic architect Howard Roark, and a Kennedy figure, all rolled into one. There’s a memorable scene where the prison warden, played by James Gandolfini, tries to break Redford’s character by making him carry heavy stones, but Redford perseveres and earns the admiration of his fellow inmates. The scene feels more like a display of Redford’s still-impressive physique at age 64 than a meaningful moment of character development. Similarly, the thriller *Spy Game*, which reunited him with Brad Pitt (who, like many young actors, had been labeled “the next Redford”), cast him in a predictable mentor role and failed to utilize his talent for portraying a world-weary but still formidable character.

Redford truly showcased his charismatic side playing a charming outlaw opposite Sissy Spacek in the 2018 film, *The Old Man & the Gun*. He did so even more powerfully in *All Is Lost*, a minimalist disaster movie where he plays a lone sailor whose yacht is destroyed in a storm. The film, reminiscent of *Jeremiah Johnson*, is a gripping survival story and arguably one of Redford’s finest performances. With only 51 lines of dialogue, the movie relies on Redford’s physical prowess and expressive acting to convey his character’s fear, resolve, and remorse. *All Is Lost* uniquely highlights his athleticism while exploring a profound theme: that life’s journey is defined by the struggle itself, a journey with the same inevitable end for everyone. In a 2013 interview with *The New York Times*, Redford perfectly captured his character’s – and perhaps his own – driving force: “You just continue. Because that’s all there is to do.”

Read More

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- He Had One Night to Write the Music for Shane and Ilya’s First Time

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- Heated Rivalry Adapts the Book’s Sex Scenes Beat by Beat

2025-09-18 00:59