Spoilers ahead for the end of A House of Dynamite, which is now streaming on Netflix.

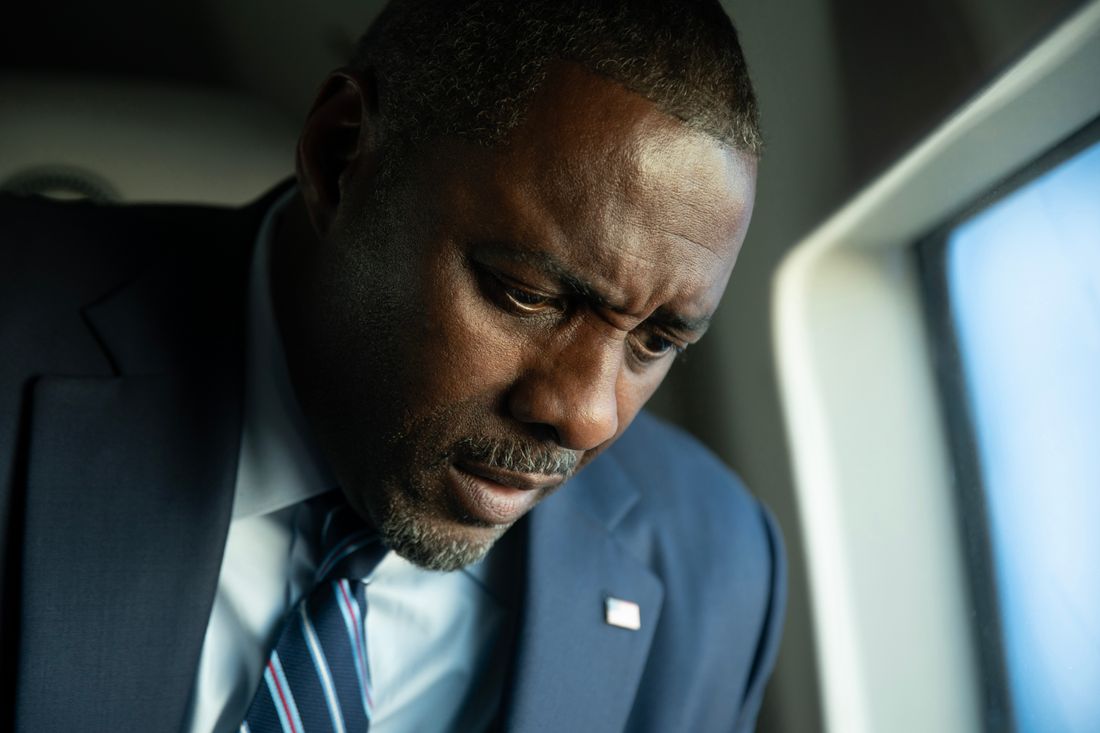

Okay, so the ending of A House of Dynamite is… something else. Basically, the movie keeps revisiting this same 20-minute crisis from different angles within the government, and just when you’re waiting to see what the President – Idris Elba, by the way – is going to do about this rogue nuclear missile headed for Chicago, it cuts away! We don’t see the missile hit, we don’t see the US respond, and honestly, we have no idea if this thing escalates into a full-blown nuclear war or if things somehow calm down. Instead, the movie ends with a bunch of ‘designated survivors’ – people who are supposed to rebuild society – heading into a bunker in Pennsylvania, just waiting to see what happens. It’s a really unsettling and open-ended finish, let me tell you.

Kathryn Bigelow’s latest film, A House of Dynamite, is likely to divide viewers, much like her recent work. It received enthusiastic praise and a long standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival, but reactions became more mixed as it screened at other festivals. The ending will probably have a similar effect, either resonating deeply with some or frustrating others – and that’s understandable! However, the ending feels consistent with the film’s overall message. Bigelow, known for exploring fragile systems and the people within them, focuses here on the hidden structures designed to protect the U.S. – and the world – from nuclear disaster. She isn’t trying to depict a specific conflict, but rather to remind us of a risk Americans have largely forgotten: the constant threat of nuclear annihilation. This sense of dread, once dismissed after the Cold War, feels increasingly relevant given the current political climate and the unsettling possibility that nuclear peace won’t last.

The film immediately addresses this unsettling idea, starting with a direct explanation: text appears on screen stating that after the Cold War, world powers agreed fewer nuclear weapons would be better. It continues, “That time is now finished.” This is followed by a massive explosion on screen – the only actual depiction of nuclear terror in the entire 100-minute film, which mostly focuses on the anticipation of it.

The film unfolds in three parts, each showing the same events from a different perspective within the government. It deliberately portrays how a potential global catastrophe would begin—with ordinary, everyday moments. Olivia Walker (played by Rebecca Ferguson, who delivers a compelling performance) cares for her ill son before going to the White House to manage the crisis from the Situation Room. Meanwhile, at the military command center responsible for nuclear strategy, General Brady (Tracy Letts) casually chats about baseball and orders coffee. Even the President is preoccupied with minor inconveniences, like a broken shoe, before attending a basketball game. Soon, however, radar detects an incoming missile. Initially dismissed as a routine test, it quickly becomes clear that this is a real, threatening ICBM aimed at the United States.

The story unfolds as characters react to a shocking discovery, their fear amplified by the technology surrounding them. Attempts to defend against the threat fail. As they realize how vulnerable their systems are, a sense of quiet dread sets in, even as they continue working with the world facing imminent danger. It quickly becomes clear that Chicago is the target, and millions of lives are at risk. The origin of the attack remains unknown, with suspicion falling on countries like North Korea or Russia. Jake Baerington, a key advisor, desperately tries to get information from Russia, but time is running out. The uncertainty is heightened by the possibility the missile might not even work, creating more fear and confusion. With no time to confirm the threat, standard procedures kick in. Some people are moved to safety while the information reaches the president, who must make an impossible choice: retaliate and risk a larger conflict, or wait and risk being attacked. This highlights the flawed logic of nuclear warfare, where deterrence can quickly turn into a dangerous trap.

Noah Oppenheim, the writer behind films like Jackie and Zero Day, directs A House of Dynamite, a film with solid direction hampered by a script that often feels awkward and overly explanatory. Dialogue sometimes feels forced, like when the Secretary of Defense (Jared Harris) randomly mentions his daughter in Chicago – a detail seemingly included just to set up a later plot point. When he ultimately takes his own life after failing to save her, it feels surprisingly predictable compared to the rest of the film’s underdeveloped characters. The script relies on clumsy shortcuts to establish character traits, as when a Secret Service agent points out that the President (Idris Elba) at least reads the newspaper, implying his virtue. Attempts to create emotional stakes also feel heavy-handed, with supporting characters revealing personal details like an impending pregnancy or marriage proposal. However, the script isn’t entirely without merit. Like other films by director Kathryn Bigelow, it possesses a directness that grounds the story in procedural realism. The film opens with a North Korean intelligence expert (Greta Lee) at a Gettysburg reenactment, a somewhat obvious but effective metaphor for a country obsessed with war games that may not be prepared for actual conflict.

The film’s straightforward portrayal of dedicated professionals working within the American defense system might strike some viewers as predictable or even supportive of traditional values—a simple ‘good ol’ boy’ depiction. This sympathetic approach could be misinterpreted as an endorsement of increased military spending. Furthermore, the film avoids political commentary and doesn’t clearly identify who launched the missile – while North Korea is heavily implied – which could lead to accusations of nationalism or an uncritical celebration of American superiority, similar to the criticisms leveled at Top Gun: Maverick. However, a more nuanced message lies beneath the surface. The failure of the defense system to prevent disaster immediately undermines the idea that a lack of funding was to blame. Baker’s frustrated question – “Is that all we get for $50 billion?” – highlights the film’s true concern: not external threats, but the inherent vulnerability of even our most elaborate safety measures. By deliberately avoiding a clear enemy, the film forces viewers to confront a deeper, more unsettling fear – a fear that can’t be easily dismissed by arguing about who is at fault.

The film A House of Dynamite is most effective when understood as a cautionary tale, one that moves beyond specific events to explore a deeper truth. Its abstract nature doesn’t hide from the central fear, but instead forces us to confront it directly, removing the possibility of blaming an external ‘other,’ like a particular government or individual. The film doesn’t offer solutions for nuclear disarmament, and that’s not its purpose. Instead, it focuses on the terrifying reality that we even arrived at a point where such a threat exists. By ending before a final outcome, the director avoids a simple explanation of cause and effect. While this ending might feel incomplete, it’s a fitting extension of the film’s initial message: this isn’t a story about the world ending, but about how easily we can forget that it could.

Read More

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- Gold Rate Forecast

- A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Season 1 Finale Song: ‘Sixteen Tons’ Explained

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- Every Death In The Night Agent Season 3 Explained

- 4. The Gamer’s Guide to AI Summarizer Tools

- Beyond Linear Predictions: A New Simulator for Dynamic Networks

- All Songs in Helluva Boss Season 2 Soundtrack Listed

2025-10-24 21:55