As a lifelong admirer and student of Hayao Miyazaki’s enchanting world of animation, I find myself utterly captivated by his latest masterpiece, “The Boy and the Heron.” Much like the boy in the story who dives into the river to reconnect with his mother, I too feel compelled to immerse myself in this heartfelt parable on grief and mortality.

Originally released on December 8, 2023, “The Boy and the Heron” can now be streamed on Max.

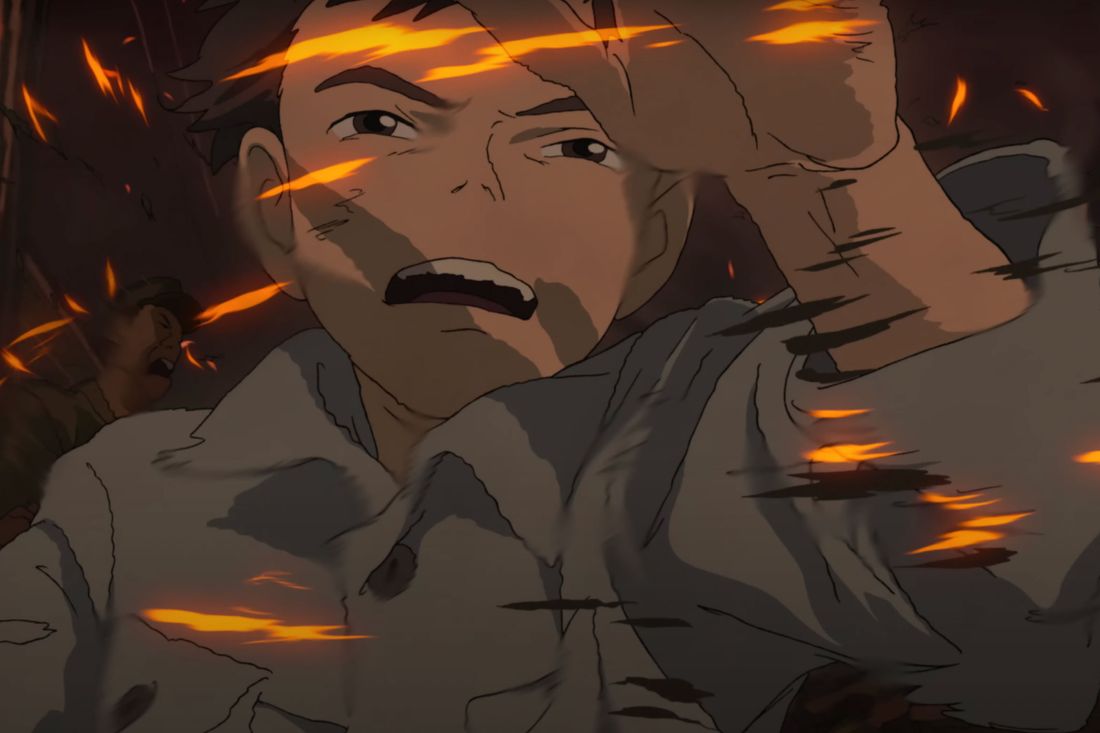

Titled “The Boy and the Heron“, the latest work by Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki, begins with a hauntingly memorable sequence of war and chaos, more somber and ominous than any previous in his filmography. The story unfolds in 1943, and our young protagonist, Mahito, hastily dons his clothes and dashes through a burning Tokyo in search of his mother. Miyazaki called upon frequent collaborator, artist Shinya Ohira, to animate Mahito’s journey through the flames. As Mahito pushes through crowds and devastated streets, both he and the bystanders around him elongate, contort, and fracture – these intentionally distorted character designs mirroring Mahito’s growing panic and disorientation amidst the smoke.

In the movie “The Boy and the Heron,” one of the most personal aspects appears to be deeply rooted in director Hayao Miyazaki’s life. Many parts of the film were influenced by his own experiences, as he explains in his book “Starting Point.” Born in 1941, Miyazaki recalls his earliest memories as scenes of destroyed cities. Like Mahito in the movie, Miyazaki was given a copy of Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel “How Do You Live?” by his mother. This book serves as both a philosophical question and the film’s title in Japan. The fear for Miyazaki’s mother, who suffered from tuberculosis during his childhood, mirrors Mahito’s anxiety about his own sickly mother. However, it’s important to note that while “The Boy and the Heron” draws on Miyazaki’s life, there are significant differences: in the movie, Mahito’s mother dies in a fire before he can reach her, whereas Miyazaki’s mother lived until 1983, outliving her son’s rise to fame in animation.

The term “semi-autobiographical” suggests a level of personal involvement in the movie that might intrigue viewers, and this description is certainly applicable to Miyazaki’s latest film, which has generated significant excitement. However, if you have closely followed Miyazaki’s work, you may notice similarities between his life and his films throughout his career. For instance, the mother of the two young girls in “My Neighbor Totoro” is hospitalized, as was Miyazaki’s own mother. In “The Castle of Cagliostro,” he animated Arsène Lupin III driving a Citroen, a car that Miyazaki himself drove for decades. Characters and themes in films like “The Wind Rises,” “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” and others can also be seen as reflections of Miyazaki’s own life experiences. Yet, it seems almost unnecessary to label these movies as “semi-autobiographical” because, like many artists, Miyazaki tends to incorporate aspects of his personal life into his work.

Mahito’s acceptance of the Heron’s character mirrors one of Miyazaki’s long-standing ideas about creative process, dating back to the 1970s. Similar to the Heron, he doesn’t view falsehoods as inherently negative. In his words, “The animator must create a lie that appears so real, viewers will believe the world depicted could be true.” This principle is evident in his works, such as the careful depiction of Prince Ashitaka straining to restring his bow in Princess Mononoke and Chihiro tapping her shoes in place in Spirited Away. These seemingly minor actions add depth and history to his characters, even though they might seem unnecessary or costly in animation. Miyazaki’s storyboards are clear, and his character designs share similarities across movies. This approach serves the production while allowing for unique details that make his characters feel lifelike. Miyazaki doesn’t replicate reality but constantly references it to tell a fantastical story that resonates with audiences. The way Mahito moves feels realistic, whether he’s attempting to cut through a fish or carving wood. However, Miyazaki also delivers surreal scenes like Ohira’s dreamlike opening, using abstract imagery to ground the fantastic in reality. Characters like the Heron and parakeet hordes may have supernatural abilities, but they still behave like real animals, adding a touch of authenticity to his work. Understanding the symbolism behind each scene and its connection to Miyazaki is part of what makes The Boy and the Heron captivating. Similarly, the film’s autobiographical elements, such as references to his relationship with his son Goro, add layers of meaning that deepen our appreciation for the work. Ultimately, Miyazaki invites his audience to bring their own experiences to his works by creatively manipulating his imagery and characters. Even in the twilight of his career, his films continue to form meaningful connections with viewers.

At the conclusion of “The Boy and the Heron”, Mahito faces a decision: either ruling over this enchanted alternate reality or returning to his own Japan – a land that Mahito and Miyazaki recognize as riddled with sorrow, paradoxes, and unattractiveness. Opting for the real world, Mahito accepts its potential hardships while simultaneously cherishing its sincerity and compassion. In a sense, Miyazaki mirrored Mahito’s existential choice by transforming the raw elements of his life to create this film. By revisiting and redrawing, time and again, the most personal and terrifying images from his early life in storyboards, Miyazaki conveyed an ultimate message of hope.

Read More

- W PREDICTION. W cryptocurrency

- Hades Tier List: Fans Weigh In on the Best Characters and Their Unconventional Love Lives

- Smash or Pass: Analyzing the Hades Character Tier List Fun

- Why Final Fantasy Fans Crave the Return of Overworlds: A Dive into Nostalgia

- Sim Racing Setup Showcase: Community Reactions and Insights

- Understanding Movement Speed in Valorant: Knife vs. Abilities

- Why Destiny 2 Players Find the Pale Heart Lost Sectors Unenjoyable: A Deep Dive

- PENDLE PREDICTION. PENDLE cryptocurrency

- How to Handle Smurfs in Valorant: A Guide from the Community

- Brawl Stars: Exploring the Chaos of Infinite Respawn Glitches

2024-09-06 22:55