Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis demonstrates the power of automated machine learning in predicting mortgage defaults, revealing key strategies for building robust and reliable models.

Careful attention to class imbalance, information leakage, and temporal partitioning is critical for accurate evaluation of machine learning models in mortgage default prediction using Fannie Mae data.

Accurate prediction of mortgage default remains a challenge despite advances in machine learning, often due to subtle data pitfalls. This paper, ‘Predicting Mortgage Default with Machine Learning: AutoML, Class Imbalance, and Leakage Control’, addresses critical issues in real-world mortgage datasets – ambiguous labeling, severe class imbalance, and temporal information leakage – to build more reliable predictive models. Results demonstrate that an AutoML approach-specifically AutoGluon-achieves state-of-the-art performance when combined with rigorous leakage control and downsampling techniques. Can these methods be generalized to other financial risk assessments where temporal data and imbalanced classes are prevalent?

The Inherent Instability of Imbalanced Prediction

The stability of the financial system is deeply intertwined with the ability to foresee mortgage defaults, as widespread defaults can trigger systemic crises. However, conventional predictive modeling techniques often falter when applied to this task due to a fundamental data imbalance. Mortgage datasets typically exhibit a disproportionately high number of borrowers who consistently meet their obligations, vastly outnumbering those who ultimately default. This skewed distribution presents a significant challenge, as algorithms tend to optimize for overall accuracy, inadvertently prioritizing the identification of non-default cases at the expense of correctly flagging genuine defaults – a critical oversight with substantial economic consequences. Consequently, models built on these imbalanced datasets may appear highly accurate but prove unreliable in identifying the very instances that pose the greatest risk to financial health.

The task of predicting mortgage defaults is fundamentally complicated by a significant imbalance in the data itself. Typically, datasets used to train predictive models contain a far greater number of instances where borrowers successfully maintain their payments than instances of actual default. This disparity creates a biased training landscape where algorithms naturally gravitate towards predicting the majority class – non-default – simply because it represents the overwhelming majority of examples. Consequently, models may exhibit high overall accuracy but perform poorly at identifying the relatively rare, yet critically important, cases of borrowers likely to default, hindering their effectiveness in risk management and potentially contributing to financial instability. Addressing this imbalance requires specialized techniques to ensure the model learns to accurately recognize patterns indicative of default, rather than simply reinforcing the prevalence of successful repayment.

Predictive models for mortgage defaults often grapple with a significant statistical challenge: the overwhelming prevalence of borrowers who consistently meet their obligations. This inherent class imbalance-where non-default cases vastly outnumber defaults-can inadvertently skew model training, causing algorithms to prioritize accurately predicting the majority class – on-time payments – at the expense of identifying genuine defaults. Consequently, models may exhibit high overall accuracy, but demonstrate poor performance in flagging actual risks, leading to an underestimation of potential losses and undermining the very purpose of default prediction. The result is a system that appears effective but fails to protect lenders and investors from substantial financial harm, highlighting the need for specialized techniques to address this critical imbalance.

The Peril of Superficial Accuracy

Downsampling is a technique used to address class imbalance in datasets by randomly removing instances from the majority class. This process aims to balance the class distribution, preventing machine learning models from being biased towards the prevalent class. While conceptually simple, downsampling can lead to information loss as potentially valuable data is discarded. The effectiveness of downsampling depends heavily on the specific dataset and algorithm used; careful consideration should be given to ensure that the reduction in majority class samples does not negatively impact the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Various downsampling strategies exist, ranging from random undersampling to more informed methods that prioritize retaining representative samples from the majority class.

Standard performance metrics, such as accuracy, precision, and recall, can provide a falsely optimistic assessment of model generalization if the evaluation data contains information leakage. This occurs when features used during training inadvertently incorporate information from the test set, leading to unrealistically high scores. Common sources of leakage include using future data to predict past events, including data from the target variable itself as a feature, or failing to properly separate training and testing sets based on a temporal or relational structure. Consequently, models appearing highly accurate during evaluation may perform poorly on genuinely unseen data, necessitating careful data preprocessing and validation strategies to detect and mitigate information leakage.

Information leakage in machine learning occurs when data used in the training process contains information that would not be available at the time of prediction. This can manifest in several ways, such as including future values of a time series as predictors, using data from the test set during cross-validation, or incorporating data created after the event being predicted. The result is an artificially inflated evaluation of model performance – metrics like accuracy or R^2 will appear higher than they would be on genuinely unseen data. Consequently, models trained with leaked information will perform poorly in production, as the predictive features available during real-world application will differ from those used during training, leading to an inaccurate assessment of its true generalization capability.

Rigorous Validation and Robust Algorithms

Temporal partitioning is a critical validation strategy in time-series modeling to mitigate information leakage. This technique involves dividing the dataset into training and testing segments based on time; training data consists of earlier time periods, while the testing data comprises later, unseen periods. By strictly adhering to this temporal split, the model is evaluated on its ability to predict future outcomes, rather than simply memorizing patterns from the entire dataset. Failure to implement temporal partitioning can lead to artificially inflated performance metrics, as the model may have access to information during training that would not be available in a real-world predictive scenario, thus providing an unrealistic assessment of its generalization capability.

Several machine learning algorithms demonstrate efficacy in predicting mortgage default. Logistic Regression provides a statistically interpretable baseline model, while tree-based methods like Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM generally achieve higher predictive accuracy. Random Forest leverages ensemble learning to reduce overfitting and improve generalization. XGBoost and LightGBM, gradient boosting frameworks, further optimize performance through techniques like regularization and efficient tree construction. The suitability of each algorithm depends on factors such as dataset size, feature importance, and the need for model interpretability, though all four have proven capable of generating reliable default predictions.

The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) is a key performance metric used to assess the ability of a model to discriminate between classes. Its robustness is particularly valuable when dealing with imbalanced datasets, where the number of instances in each class differs significantly. In mortgage default prediction modeling, AutoGluon demonstrated strong performance, achieving a peak AUROC of 0.8230 when evaluating a 1:2 ratio of positive to negative examples; this indicates a higher capacity to correctly identify defaults relative to non-defaults under these conditions, and surpasses the performance of other tested models at the same ratio.

XGBoost, when applied to the mortgage default prediction task at a 1:2 positive-to-negative ratio, demonstrated a training Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.8902. However, performance on unseen data, as measured by the test AUROC, was 0.8112. This difference of 0.0788 between training and test AUROC indicates a degree of overfitting, where the model performed well on the data it was trained on but generalized less effectively to new, unseen data. While still a strong result, the discrepancy highlights the importance of techniques like temporal partitioning to assess true predictive power and prevent artificially inflated performance metrics.

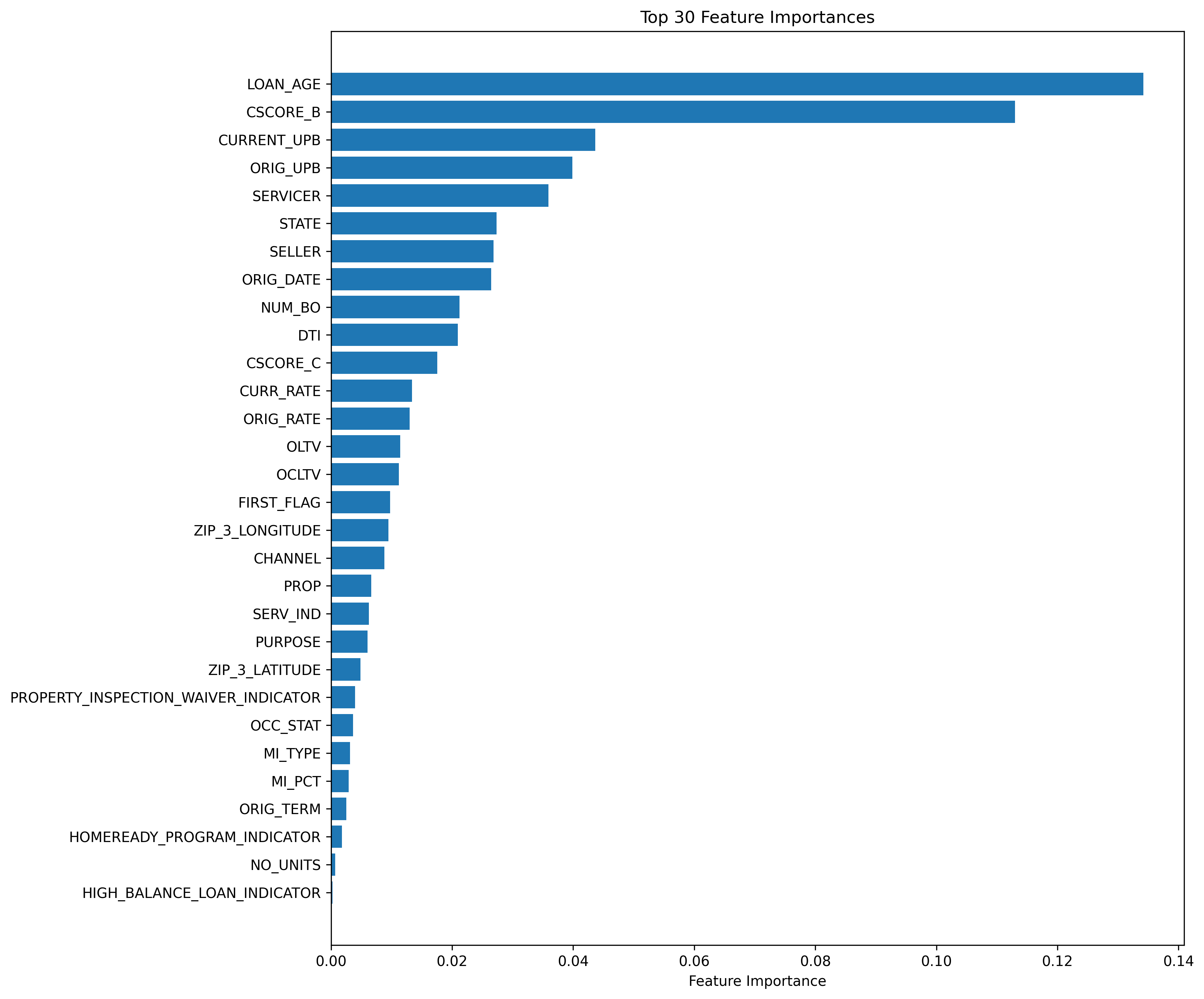

The Significance of Predictive Features

Feature importance analysis serves as a critical component in understanding the drivers of mortgage default risk. By systematically evaluating the predictive power of various borrower and loan characteristics, researchers and lenders can pinpoint the variables that most strongly correlate with repayment difficulties. Analyses consistently reveal that factors like credit score, loan-to-value ratio, and debt-to-income ratio are consistently among the most influential predictors. However, the specific weight assigned to each feature can shift based on the economic climate and the composition of the loan portfolio, necessitating ongoing monitoring and recalibration of predictive models. Beyond simply improving accuracy, identifying key features provides valuable insight into why defaults occur, enabling more targeted risk mitigation strategies and potentially informing policies designed to support responsible lending practices.

The widely utilized Fannie Mae Single-Family Loan Performance Data presents unique challenges regarding information leakage, a critical concern in predictive modeling. This dataset, detailing the life cycle of mortgage loans, contains variables reflecting events after a loan’s origination that could inadvertently signal future default if improperly used. For instance, including variables that capture post-default servicing costs or foreclosure timelines introduces information about the outcome being predicted, creating an unrealistically optimistic model performance. Rigorous data preprocessing, therefore, is paramount; analysts must meticulously identify and exclude ‘look-ahead’ variables to ensure the model accurately reflects predictive power based on information genuinely available at the time of loan origination, rather than relying on knowledge of subsequent events. Failure to address this can lead to models that perform well on historical data but fail catastrophically when applied to new, unseen loans.

Automated machine learning, or AutoML, presents a significant opportunity to accelerate the development of predictive models for complex financial challenges like mortgage default prediction. These systems automate many steps of the modeling pipeline, from feature engineering to model selection and hyperparameter tuning, greatly reducing the time and expertise traditionally required. Recent evaluations utilizing the Fannie Mae Single-Family Loan Performance Data demonstrate this potential; the AutoGluon framework, for example, achieved a training Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.9567 at a 1:2 training-to-validation data ratio. However, successful implementation necessitates careful attention to potential data pitfalls, such as information leakage, which can lead to overly optimistic performance estimates and flawed models deployed in real-world scenarios.

The pursuit of accurate mortgage default prediction, as demonstrated by this work with AutoGluon, echoes a fundamental principle of mathematical rigor. Every feature selected, every parameter tuned, must contribute to a demonstrably correct model – not merely one that performs well on a limited test set. As Blaise Pascal observed, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” This seemingly unrelated insight speaks to the need for disciplined model building; resisting the temptation to overcomplicate, and instead focusing on a minimalist, provably sound solution. The careful attention to temporal partitioning and leakage control isn’t simply about avoiding bias; it’s about ensuring the underlying logic remains unassailable, a pursuit of mathematical purity in a practical application.

Beyond Prediction: The Rigor Yet to Come

The demonstrated efficacy of automated machine learning-specifically, AutoGluon’s performance-should not be misconstrued as a resolution. Rather, it highlights the persistent inadequacies in defining ‘good’ prediction within this domain. A high area under the curve is a number, not a guarantee of robustness, and a formally proven algorithm remains the gold standard. The observed gains from temporal partitioning and judicious feature selection are, in essence, damage control-attempts to mitigate the inevitable noise introduced by poorly defined data and the inherent instability of empirical relationships.

Future work must shift focus from merely achieving incremental gains in predictive power to establishing mathematically sound foundations. The concept of ‘default’ itself requires precise axiomatic definition, divorced from the vagaries of observed behavior. Furthermore, the problem of class imbalance is not solved by algorithmic tricks, but by a deeper understanding of the underlying generative process-a process currently treated as a black box.

Until predictive models are constructed not through empirical optimization, but through deductive reasoning from first principles, they will remain sophisticated approximations-elegant, perhaps, but ultimately unsatisfying. The pursuit of true understanding demands a commitment to formal verification, not merely to the appearance of success on held-out test sets.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.00120.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- Heated Rivalry Adapts the Book’s Sex Scenes Beat by Beat

- EUR INR PREDICTION

- He Had One Night to Write the Music for Shane and Ilya’s First Time

2026-02-03 09:50