As a film enthusiast who has spent countless hours immersed in the rich tapestry of American cinema, I find myself consistently astounded by Francis Ford Coppola‘s body of work. His films not only captivate audiences with their riveting narratives and technical prowess but also resonate deeply with the complexities of the human experience, particularly as it pertains to immigration and the pursuit of the American Dream.

This list was originally published on April 5, 2018. It has been updated to include Megalopolis.

Throughout the various stages of Francis Ford Coppola’s 50-year career – from the carefree ’60s, the grandiose visions of the ’70s, the tumultuous experiences in Hollywood during the ’80s and ’90s, the self-exploratory projects of the early 2000s – a recurring theme is an Italian-American interpreting America’s story from the perspective of outsiders. The Corleone family from the Godfather trilogy stands out as the most notable instance, but it also includes the hippies in Finian’s Rainbow, the displaced housewife in The Rain People, the Oklahoma teenagers in The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, the people affected by healthcare issues in The Rainmaker, and the soldiers in Apocalypse Now and Gardens of Stone, who didn’t have the luxury to avoid service due to bone-spur deferments. Moreover, Coppola himself, a recluse in many ways, was committed to creating art within the Hollywood system that frequently urged him toward concessions or even expulsion.

Ranking Francis Ford Coppola’s 23 films, excluding his soft-core film “Tonight for Sure,” the short feature “New York Stories,” and the Disney attraction “Captain EO,” was a challenging task. His peak during the ’70s mirrored that era’s brilliance, but arranging masterpieces like the first two “Godfather” movies, “The Conversation,” and “Apocalypse Now” in a specific order is agonizing, as they could be ranked differently on any given day. The remainder of his films fall into what we’ll call the “S.E. Hinton Conundrum,” named after “The Outsiders” and “Rumble Fish,” two distinct adaptations of S.E. Hinton’s works made by Coppola in the same year. We favored the experimental films, even though they were less appreciated by critics and audiences at the time. His latest (and potentially last) film, “Megalopolis,” certainly fits this pattern – it’s the kind of audacious disaster that only Coppola would dare to create.

Jack is the worst, though. On that point, we can surely agree.

23.

Jack (1996)

In Coppola’s career, Jack stands out as a film that is difficult to defend, serving as a stark reminder of how easily Big could have taken a turn for the worse. Unlike Tom Hanks’ character in the earlier film, Robin Williams portrays a man-child who is not striving to grow older but rather a lonely, awkward, and clumsy kid trapped in a 40-year-old’s body. What makes Jack unsettling is the frequent encounters this character has with adult sexuality: He has an attractive mother (Diane Lane), a seductive teacher (Jennifer Lopez), and a single parent (Fran Drescher) who persistently pursues him, and he forms friendships through buying Penthouse magazines. (This is all before the discomfort of Bill Cosby in a significant role.) There’s a hint of Coppola’s style in the depiction of childhood purity preserved in an adult form, but it requires a keen eye to discern it.

22.

Dementia 13 (1963)

Numerous renowned directors emerged from the filmmaking school led by Roger Corman, but Francis Ford Coppola’s initial directorial venture, disregarding his soft-core production “Tonight for Sure“, was quite an intense learning experience. With only leftover funds from another Corman project, Coppola was tasked to create a budgetless version of “Psycho>” within nine days in Ireland. The resulting film, “Dementia 13“, required extensive reshoots by Corman for its release due to its raw and unrefined nature. However, Coppola’s script presents a clever reinterpretation of “Psycho>”, featuring a widow (Luana Anders) who journeys to an Irish castle to claim her inheritance, only to uncover a host of family secrets shrouded in darkness instead. Additionally, Coppola successfully executes a few captivating sequences, such as the husband’s demise while a radio plays rockabilly music on his descent into the lake or the reappearance of a deceased girl’s toys, triggering a psychological meltdown.

21.

Gardens of Stone (1987)

Coppola designed Gardens of Stone as a counterpart to Apocalypse Now, a poignant military tale that chronicles the aftermath of the Vietnam War, portraying the lifeless and broken spirits returning home or being laid to rest in the serene Arlington National Cemetery. James Caan delivers an exceptional performance as a career soldier who questions the war’s morality, while sharing a genuine camaraderie with James Earl Jones, his old Korean War comrade and superior officer. However, the raw energy and unpredictability that made Apocalypse Now so captivating is lost in the film’s excessive focus on military protocol. Coppola effectively captures the internal conflict of officers honoring their fallen comrades during an unnecessary and unwinnable war, but the narrative feels rigid and conventional.

20.

Finian’s Rainbow (1968)

In the late 1960s, many Hollywood movies were attempting to blend the dreamlike appeal of conventional studio productions with the emerging wave of societal and political upheaval. However, few films displayed this conflict as awkwardly as “Finian’s Rainbow,” a musical that takes mid-century Broadway shows and gives them a hippie facelift. Coppola persuaded Fred Astaire to come out of retirement to portray a carefree Irishman who hides a pot of gold in a valley near Fort Knox, believing it will increase in the fertile soil. Despite the bright atmosphere and musical performances, the setting and storyline hide a very modern clash between an idealistic commune composed of various characters and the corrupt police and politicians determined to suppress them. In essence, “Finian’s Rainbow” envisions drastic transformation, but its cinematic portrayal is far from revolutionary.

19.

Twixt (2011)

In simpler terms, “Twixt,” one of Coppola’s more recent ventures into independent, semi-experimental cinema, while not his best work, offers an intriguing exploration of his personal and cinematic history. It recalls the gritty genre style of “Dementia 13” and the tragic loss of his son Gian-Carlo in a boating accident. The film uses 3-D for some sequences and a dim, digitally muted aesthetic for others. Val Kilmer plays a budget Stephen King character who transforms a dull book signing into an investigation of an unsolved local murder mystery. “Twixt” is an unusual, partially developed film, but it’s a small delight for Coppola enthusiasts, who can spot references to Corman, Edgar Allan Poe, William Castle, and “Nosferatu,” and view the project as a collection of notes adding depth to his career.

18.

Megalopolis (2024)

Over four decades in development, Coppola’s ambitious project, the reconstruction of a significant American city following a catastrophic event, appears to be the swan song of a daring filmmaker who has never shied away from pouring his own $120 million and personal investment into his grand, impractical artistic visions. However, there’s a thin border between the exhilarating audacity and madness of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and the disjointed, erratic science fiction of Megalopolis, which aspires to the optimistic idea that humanity can construct a utopia from the fall of New Rome but often falters in its execution. Apart from Adam Driver’s passionate portrayal of an architect who is both mercurial and magical, Coppola has limited control over performances that tend towards the exaggerated, and the digital effects have a cheap, generic quality lacking the richness of his best work. Despite this, Megalopolis is overflowing with inspiration and unbridled energy, making its remarkable scenes and less successful ones equally captivating – and it’s challenging to find agreement on which ones are which.

17.

Youth Without Youth (2007)

In simpler terms, after a ten-year hiatus from movie production, Coppola came back with his toughest and most self-reliant work yet – a fantasy about eternal youth and rekindled love that eventually turns into a nightmare. Essentially, it’s like an art-damaged version of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. The story revolves around an old Romanian linguistics professor (Tim Roth) in 1938 who is struck by lightning and starts to grow younger. This confuses his doctor (Bruno Ganz), intrigues the invading Nazis, and initially makes the film seem like a celebration of deadline extensions. However, Youth Without Youth evolves into a profound exploration of aging, consciousness, spirituality, and 20th-century evil. While there are many ideas at work here, Coppola injected a much-needed burst of energy into American independent cinema, which was struggling to move out of its Brooklyn apartment.

16.

You’re a Big Boy Now (1966)

In a similar vein to how “Who’s That Knocking at My Door?” marked the start of Martin Scorsese’s career, and “Greetings” and “Hi, Mom!” did for Brian De Palma, “You’re a Big Boy Now,” an MFA project from UCLA by Coppola, serves as a raw precursor to his future brilliance. Adapted from David Benedictus’s book, the film mirrors the mischievous tone of early De Palma works or offers a low-budget American take on the hipster comedy seen in “The Knack… and How to Get It.

15.

The Godfather Part III (1990)

In “The Godfather” trilogy, the theme of authenticity as an American versus an immigrant has been a lingering concern since its inception, and “The Godfather Part III” offers a poignant observation on how wealth can mask even the most heinous crimes. The narrative begins with the audacity of Michael Corleone being honored by the Vatican for a large donation, followed by his descent into a self-inflicted catastrophe. While Coppola manages to give the Corleone saga a fitting and conclusive Shakespearean structure, the film seems to lack the inventive spirit and intensity of its predecessors. Moreover, Sofia Coppola’s portrayal in a pivotal role is criticized as detrimental to the movie; she serves as the cornerstone of the storyline – representing Michael Corleone’s potential redemption and eventual downfall – but her performance weakens the overall narrative.

14.

The Cotton Club (1984)

In an attempt to get out from under the mountain of debt he owed Zoetrope Studios and perhaps regain his tarnished reputation, Coppola entered into a questionable agreement by collaborating once more with Robert Evans, producer on his Godfather series, and Mario Puzo, the screenwriter. Together they crafted another visually striking story about organized crime, entitled The Cotton Club. Similar to many of his 80s productions, Coppola’s focus on creating a captivating atmosphere for the film surpassed his attention to the plot itself, which is rather uneventful, especially when trying to intertwine the tale of an aspiring jazz musician (Richard Gene) with the conflicts among gangs and racial tensions. However, Coppola and his team have recreated the renowned Harlem nightclub so lavishly that it often overshadows the lackluster storyline, particularly when the camera pans to the stage and the musical performances take center stage, featuring the tap-dancing duo of Gregory and Maurice Hines, as well as Lonette McKee’s rendition of a Lena Horne-inspired performance. Ultimately, Coppola cannot conceal where his genuine passions reside.

13.

The Rainmaker (1997)

In the ’90s, numerous renowned directors found themselves spinning different takes on the same theme inspired by John Grisham’s idealistic young lawyer battling the system – even esteemed Robert Altman joined the fray with “The Gingerbread Man” – but “The Rainmaker” surpasses its mediocre reputation. Originating from the ruins of the Clinton healthcare initiative, this film transforms a lawsuit against an unscrupulous insurance company into a passionate plea against a system that often neglects and even endangers the most vulnerable among us. Coppola creates a David versus Goliath scenario between Matt Damon’s green law-school graduate and a horde of corporate lawyers (headed by Jon Voight), which mirrors the challenges faced during health-care reform at that time, making it both highly engaging and reflective of reality. A romantic storyline involving Damon and a battered wife (Claire Danes) could have been omitted without much notice or concern, but Coppola, who is no stranger to challenging the status quo, uses this film effectively to criticize an injustice prevalent at that time.

12.

The Outsiders (1983)

1983 saw Coppola bring to life two novels by S.E. Hinton for the cost of two, commencing with “The Outsiders”. This film can be seen as Coppola’s nostalgic reinterpretation of a James Dean drama, featuring sensitive bad boys who represent a generation of lost and marginalized youth. The story is set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during 1965, where two “Greasers” (portrayed by C. Thomas Howell and Ralph Macchio) flee after fatally attacking a member of the wealthy rival gang, the Socs. Much like “West Side Story”, the film’s tale of street toughs is questionably credible, and it hinges on an implausibly absurd plot device. However, it stands alone as a star-studded lineup (including Matt Dillon, Patrick Swayze, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, and Diane Lane). Coppola’s empathy is evident in the stunning portrayal of a Tulsa frozen in time, shrouded by dust and twilight. A scene outside a rural church at dusk, where Howell and Macchio contemplate their uncertain future, is as moving as any ’80s cinema has to offer.

11.

Rumble Fish (1983)

In a sense where Coppola’s Hinton adaptations were seen as a “something for them, something for me” approach, it can be said that Rumble Fish is undeniably the “something for me,” given the director’s apparent departure from traditional storytelling methods. The script, pieced together, leans more towards atmosphere rather than a conventional narrative, featuring Matt Dillon as a sensitive street tough and Mickey Rourke as his troubled older brother, whose vow to abstain from gang fights doesn’t lessen his capacity for violence or the conflicts that built up during his rule of the streets. Filmed in radiant black and white with an experimental score by Stewart Copeland, Rumble Fish distills the conflict into pure abstraction, allowing visuals and sound to fill in the gaps. The only splash of color appears in the Siamese fish at a pet store, each confined to their own space in the tank or they’d fight each other – a striking visual metaphor for fragile, self-destructive youth. The film is largely supported by this poetic visual symbol.

10.

Tetro (2009)

In composing his first original screenplay since “The Conversation”, Coppola delved into his family history to create this melodramatic trinket that portrays the tense rivalry between two brothers, influenced by their formidable father. While the setting is modern-day Buenos Aires, Argentina, the story appears to be set decades ago, owing to the captivating black-and-white cinematography which lends an enchanting Old World charm to the city. The relationship between Alden Ehrenreich and Vincent Gallo mirrors that of Matt Dillon and Mickey Rourke in “Rumble Fish”, but the narrative’s foundation in musical and theatrical aspirations aligns it more closely with Coppola’s personal interests, leading him to emphasize Buenos Aires’ cosmopolitan allure. Although his emotional investment in the plot might be minimal, Buenos Aires hasn’t radiated such an enchanting glow since Wong Kar-wai’s “Happy Together”.

9.

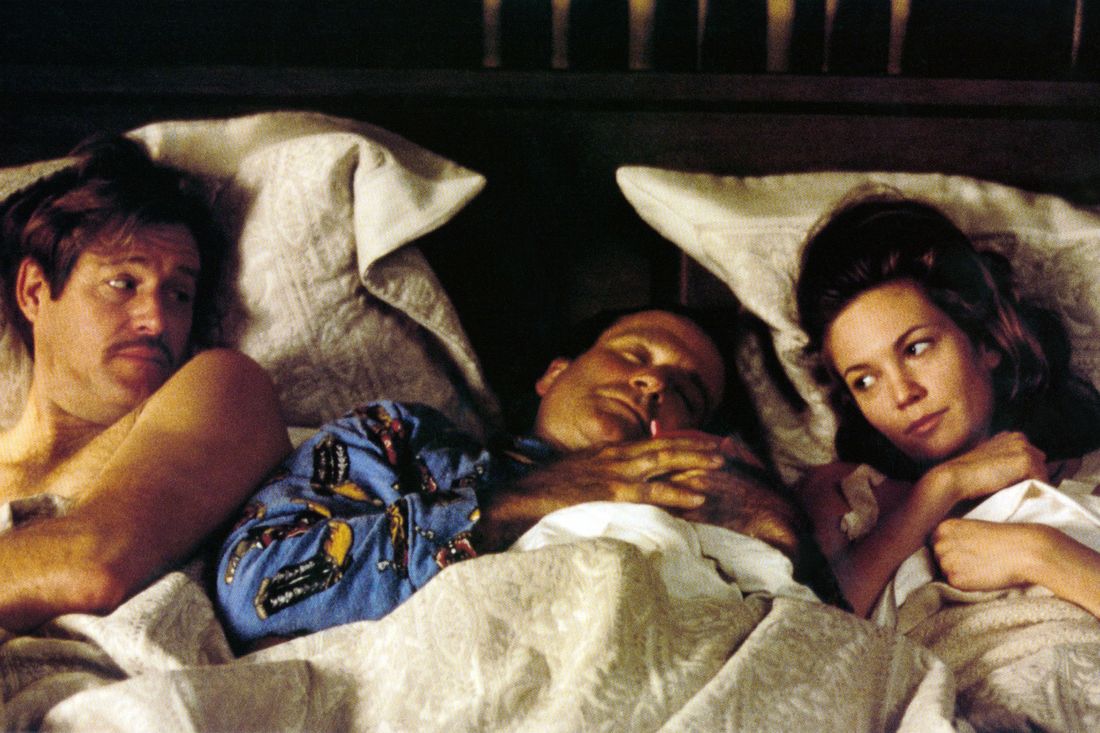

One From the Heart (1982)

This movie, “One From the Heart,” was a costly disaster for director Francis Ford Coppola, both spiritually and financially. Despite being funded heavily through Zoetrope Studios, it barely managed to recover its production costs. Some might argue that the blend of domestic melodrama and Hollywood glamour in this musical was groundbreaking. However, the film falls short: Teri Garr and Frederic Forrest struggle to convincingly portray their stormy marriage and navigate the Las Vegas night, while Tom Waits’s bluesy songs, sung in non-diegetic duet with Crystal Gayle, seem disconnected from the action. Yet, only a true artist could fail as magnificently as Coppola does here. With Vittorio Storaro as his cinematographer and Dean Tavoularis on production design, Coppola’s Las Vegas is a visual spectacle that brims with vibrant colors and romantic potential. It’s a shame that more mainstream successful films don’t aspire to such grandeur.

8.

Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

A year following “Back to the Future,” Coppola found himself still paying off debts from Zoetrope by creating another tale involving time travel, this time focusing on going back to the past and straightening out the present. This studio role suited Coppola well, as he infused a charming sense of nostalgia into the 1960s small-town setting and primarily handed the film over to Kathleen Turner. Turner, in her role as Peggy Sue, is transported back in time during her high school reunion and finds herself contemplating the significant question of whether she’ll pursue a relationship with a young man (Nicolas Cage) who may disappoint her in marriage, but first, she enjoys reuniting with her family and friends, and revisiting her lost youth. Coppola began to explore the concept of eternal youth in this film, a theme he would revisit in “Jack,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” and “Youth Without Youth,” but its pleasures transform into a more contemplative blend of comedy and drama about living with the decisions we’ve made.

7.

The Rain People (1969)

In a less frequently recognized work from Coppola’s filmography, this road journey might be seen as a feminist counterpart to “Easy Rider,” albeit more rooted in the widespread unease and desire for adventure that swept across America during the late ’60s. The protagonist, Shirley Knight, portrays a housewife who unexpectedly discovers she’s pregnant and embarks on a journey without a set destination, embodying women who felt trapped by traditional gender norms. Yet, her quest for freedom is uncertain—she’s unsure if or where this liberation lies. James Caan delivers a poignant performance as an ex-football player struggling with head injuries, and Robert Duvall portrays a controlling state trooper vying for her sympathies. The conclusion is chaotic, but “The Rain People” reaches it through an unforeseen and dreamlike exploration of America’s emerging landscapes, as well as one woman’s courageous quest to find her place within it.

6.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Indeed, Keanu Reeves might not be the ideal choice for a 19th-century nobleman, and Anthony Hopkins’ portrayal of Van Helsing is so over-the-top it could double as holiday fare. The movie’s dialogue and atmosphere veer towards excessive flamboyance, teetering on the brink of camp. However, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a visual treat, boasting Michael Ballhaus’ vibrant colors, traditional in-camera effects, Eiko Ishioka’s intricate costumes, and Wojciech Kilar’s score that elicits the deepest tones from the orchestra and choir. Francis Ford Coppola has previously been salvaged by technical achievements, but here he chose to emphasize the romantic aspects of the Dracula legend boldly and dramatically, resulting in a horror film that pulsates with emotion. Notably, Gary Oldman’s Count stands out among the diverse performances: He presents a stark contrast to Max Schreck’s Nosferatu, portraying a sorrowful figure who has borne a curse for centuries.

5.

Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988)

In a career spanning over a decade marked by creative restraints, Coppola used the tale of Preston Tucker and his revolutionary 1948 Tucker Torpedo as a poignant symbol reflecting his own struggle as an aspiring innovator. By portraying Jeff Bridges as a radiant visionary striving to build the future car, yet facing betrayal from his board and legal troubles with the SEC for alleged stock fraud, Coppola allegorically depicts the Big Three automakers as a metaphor for the Hollywood studio system. Tucker: The Man and His Dream underscores how American capitalism prioritizes established power and mass-produced mediocrity at the expense of the underdog. This compelling film, much like the Tucker sedan, gleams with production quality and smoothness, but it also serves as a powerful personal testament from Coppola, expressing his disillusionment with Hollywood in the ’80s. Just as only 50 Tuckers managed to be produced, so too did Coppola’s dream for his own studio falter, yet he clings to the hope that its vision will endure.

4.

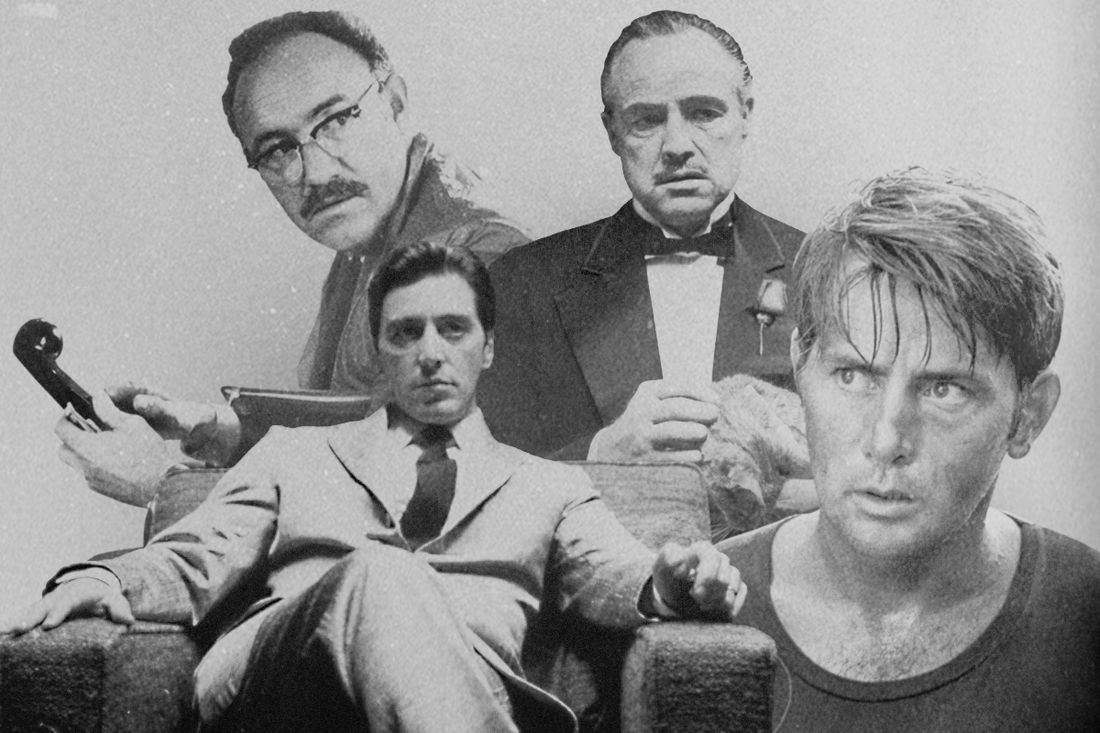

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Transforming Joseph Conrad’s novel “Heart of Darkness” into a powerful symbol of the chaos and insanity of the Vietnam War, Coppola found himself mirroring the same perilous voyage downstream, transforming his filmmaking process into a 16-month ordeal in the Philippines. Coppola’s statement about the completed movie (“Apocalypse Now is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.”) invited ridicule, but in his relentless pursuit to pour money and resources into an ambiguous and essentially unfinishable project, Coppola provided a more raw and authentic portrayal of the war than a more organized production could have achieved. The film “Apocalypse Now” operates like a waterborne road trip: As Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) and his crew navigate the river to find the renegade Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), Coppola is given the freedom to confront them with all the surrealistic diversions he can imagine, from spectacular scenes such as helicopters attacking to the sound of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” to grotesque characters like Robert Duvall’s surf-obsessed Kilgore and Dennis Hopper’s drug-addled photographer. Coppola is more concerned with the psychological aspect of the war rather than its historical reality, and the film effectively brings a terrifying dreamscape to life.

3.

The Godfather (1972)

The classic movie “The Godfather,” written by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola, is filled with unforgettable scenes such as a valuable horse’s head appearing in a studio executive’s bed, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) committing a double murder at a Bronx eatery, Sonny (James Caan) being killed in a tollbooth ambush, Don Vito (Marlon Brando) collapsing with a heart attack while chasing his grandson around the garden, and coordinated attacks on four rival families during a baptism. However, what truly sets “The Godfather” apart is Coppola’s deep insight into Italian-American culture, portraying the Corleones as an extreme depiction of an immigrant family that straddles both their native roots and their adopted homeland. The film begins with the statement “I believe in America,” only to expose the vast disparity between the romanticized American Dream and the ruthless methods the Corleone family employs, operating outside the law as they strive for legitimacy, ultimately finding corruption instead.

2.

The Godfather Part II (1974)

Instead of merely capitalizing on Puzo’s violent gangster tales in The Godfather‘s sequel for financial gain, The Godfather Part II transcends this by being one of the greatest American films depicting the immigrant experience. The poignant shot of a weak, sickly young Don Vito on Ellis Island gazing at the Statue of Liberty sets the stage for a multi-decade exploration of a nation where opportunities are seized rather than handed out, often through violence and underhanded dealings. Coppola skillfully interweaves scenes of Vito as a young man, portrayed by Robert De Niro, with the ongoing saga of Michael Corleone, the family’s head, capturing the poisonous legacy passed down from one generation to the next and the full, tragic narrative of their lives. Not content to leave any studio money behind, Coppola broadens the scope of The Godfather Part II to encompass turn-of-the-century New York City, the dissolute end of Batista’s Cuba, and even a glimpse of Sicily itself, where Vito returns to settle an old score. However, the film fundamentally delves into what true social mobility in America means for the Corleones and the heavy toll it takes on their souls.

1.

The Conversation (1973)

45 years since the release of “The Conversation”, it’s striking to consider how deeply its themes of surveillance and government intrusion have permeated American culture, to the extent that we willingly share personal information that once was meticulously guarded by characters like Harry Caul (Gene Hackman). Coppola creatively transfers the visual deception of Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blowup” into a sound-based narrative, following Hackman’s surveillance expert as he unravels a conversation in San Francisco’s Union Square and becomes convinced of an impending dangerous event. Pioneering a wave of post-Watergate thrillers including “The Parallax View” and “All the President’s Men”, “The Conversation” capitalizes on the uneasy climate of a nation where trust in official information was eroding, and where conspiracies began to proliferate. Simultaneously, it serves as an astute commentary on the filmmaking process itself and the deceptive nature of blending sound and visuals. The film’s relevance continues to grow year after year due to Coppola’s insight into the direction the country was taking. We find ourselves all living as Harry Caul and his saxophone, expressing dismay in a world where true privacy is increasingly elusive.

Read More

- ACT PREDICTION. ACT cryptocurrency

- W PREDICTION. W cryptocurrency

- Hades Tier List: Fans Weigh In on the Best Characters and Their Unconventional Love Lives

- Smash or Pass: Analyzing the Hades Character Tier List Fun

- PENDLE PREDICTION. PENDLE cryptocurrency

- Why Destiny 2 Players Find the Pale Heart Lost Sectors Unenjoyable: A Deep Dive

- Sim Racing Setup Showcase: Community Reactions and Insights

- Understanding Movement Speed in Valorant: Knife vs. Abilities

- How to Handle Smurfs in Valorant: A Guide from the Community

- NBA 2K25 Review: NBA 2K25 review: A small step forward but not a slam dunk

2024-09-27 21:55