As someone who has spent decades immersed in the world of wildlife documentaries and conservation efforts, I find myself deeply moved by the stories of Eric Goode and his work, as portrayed in this article. It’s clear that he walks a delicate line between entertainment and education, often finding success where others might fail.

heads up: the story below might give away small surprises from episodes of HBO’s Chimp Crazy that haven’t been aired yet. If you want to watch the September 8 finale without knowing anything in advance, consider reading this at a later time instead.

Let’s see if we can get them to mate.”

Eric Goode, renowned conservationist and producer of the 2020 Netflix series “Tiger King,” is eager to provide me with a show. On a bright June day at the Turtle Conservancy in Ojai, California, a sanctuary for endangered turtles and tortoises that he manages close to his residence, we’re standing by a pen filled with plowshare tortoises, among the world’s rarest creatures. Goode instructs an employee to position a male next to one of the females. “He’ll keep circling her,” explains Goode, “and then he’ll use his gular scute, which is a bony plate located under his chin, to flip her over.” He describes it as a very aggressive mating ritual.

We gave it some time, but unfortunately, we didn’t observe any circling, flipping, or mating behaviors. It seems that the male plowshare is either not in the mood or taking his time to initiate activities, so he went back to his own habitat. “Let’s check out something else,” Goode suggests, and he escorts me into a greenhouse where Simon Rouot, the facility’s associate director from France, shows a Burmese star tortoise.

Upon our return to the outdoors, there’s an unexpected treat in store. In a neighboring enclosure, a sizable Madagascar radiated tortoise appears to be passionately courting another. “These are radiated tortoises from Madagascar,” Goode notes amidst the echo of their shells colliding, “and they have quite an insatiable desire for mating.”

“And they’re both males,” says Rouot.

“Well,” says Goode, “that’s what happens when you deprive them of females.”

I bring up the scene above for more reasons than just entertainment; it aligns perfectly with Goodes’ typical documentary themes. It features unusual animals, peculiar individuals, and an unexpected turn of events that enhances any initial plans Goodes might have had.

As a movie enthusiast, I’d say my documentary, “Tiger King,” initially started off as a light-hearted, Best in Show-esque comedy, following eccentric tiger owners, each more unique than their feline counterparts. But things took an unexpected turn when the film’s main subject, Joe Exotic, a zookeeper from Oklahoma, requested an undercover FBI agent to take out his arch-nemesis, Carole Baskin – a woman who, according to the series, might have had a darker past involving her former husband’s disappearance and tiger feedings. However, it’s crucial to note that the show never provides concrete evidence to support these allegations against Carole Baskin.

Goode’s recent project, Chimp Crazy, took an unexpected turn from its initial beginnings. This intriguing documentary, now airing on HBO, delves into the peculiarity of surrogate chimp mothers – human women who nurture chimpanzees as if they were their own children, a situation that more often than not leads to unfortunate outcomes. As they reach maturity, these primates can exhibit aggressive behavior, especially when kept in cramped spaces like homes and deprived of contact with other primates.

You might not recognize the name Goode, despite being among the multitude who watched Tiger King. He’s not very prominent in his work, often staying out of the camera or voice-over limelight. In another era, he was a hotel and nightclub tycoon in New York, an unexpected foray into filmmaking. Yet, with one captivating and unforeseeable animal documentary under his belt, followed by another potentially more shocking one, he appears to be on the path to becoming a well-known figure.

To become the current sensation in documentarian work, one that balances commercial success with an avant-garde spirit reminiscent of filmmakers like John Waters and Harmony Korine, you’ll need several key elements. First, you’ll require financial resources. Second, a unique vision is crucial. Third, you should have a strong aversion to the conventional content production of streaming-TV industries. Lastly, be prepared to bend or even break some journalistic norms.

It’s quite astonishing how Eric Goode seems to be always at the right place and time. After watching Tiger King, many viewers thought it was too unbelievable to be a genuine documentary. If I were a critic, I might question how it’s possible that this filmmaker began documenting Joe Exotic, then Joe attempted to kill Carole, and later the same filmmaker produced another documentary where the woman he filmed ended up kidnapping a chimpanzee. Such events seem too coincidental. However, there’s nothing in Tiger King or Chimp Crazy that was fabricated or staged. It’s understandable for people to be skeptical given the improbability of these occurrences happening consecutively.

Goode’s house, nestled at the foot of the Topatopa Mountains, approximately 90 minutes northwest from L.A., is camouflaged among the trees and can be hard to spot from the main road – a deliberate choice, it seems. The property houses various reptile species, some of which are believed to be extinct in their natural habitats, making them highly sought after on the black market. On my initial visit, he provided me with directions and the gate’s access code over the phone.

Upon my arrival, Goode is engaged in a conversation with his executive producer and close collaborator Jeremy McBride, who’s currently overseeing the final color adjustments for the documentary titled “Chimp Crazy” this week. The film’s title has recently been decided upon, but Goode expresses a mix of feelings about it. “HBO found ‘Chimp Crazy‘ appealing,” he notes, “but it wasn’t my top choice. I preferred ‘Humanzee‘, a name Tonia used to refer to Tonka because he was a chimp living in the human world, which is essentially the story’s theme. However, HBO had concerns about people understanding how to pronounce it. For a brief moment, I considered titling it ‘Apeshit‘, but they weren’t fond of that suggestion either.”

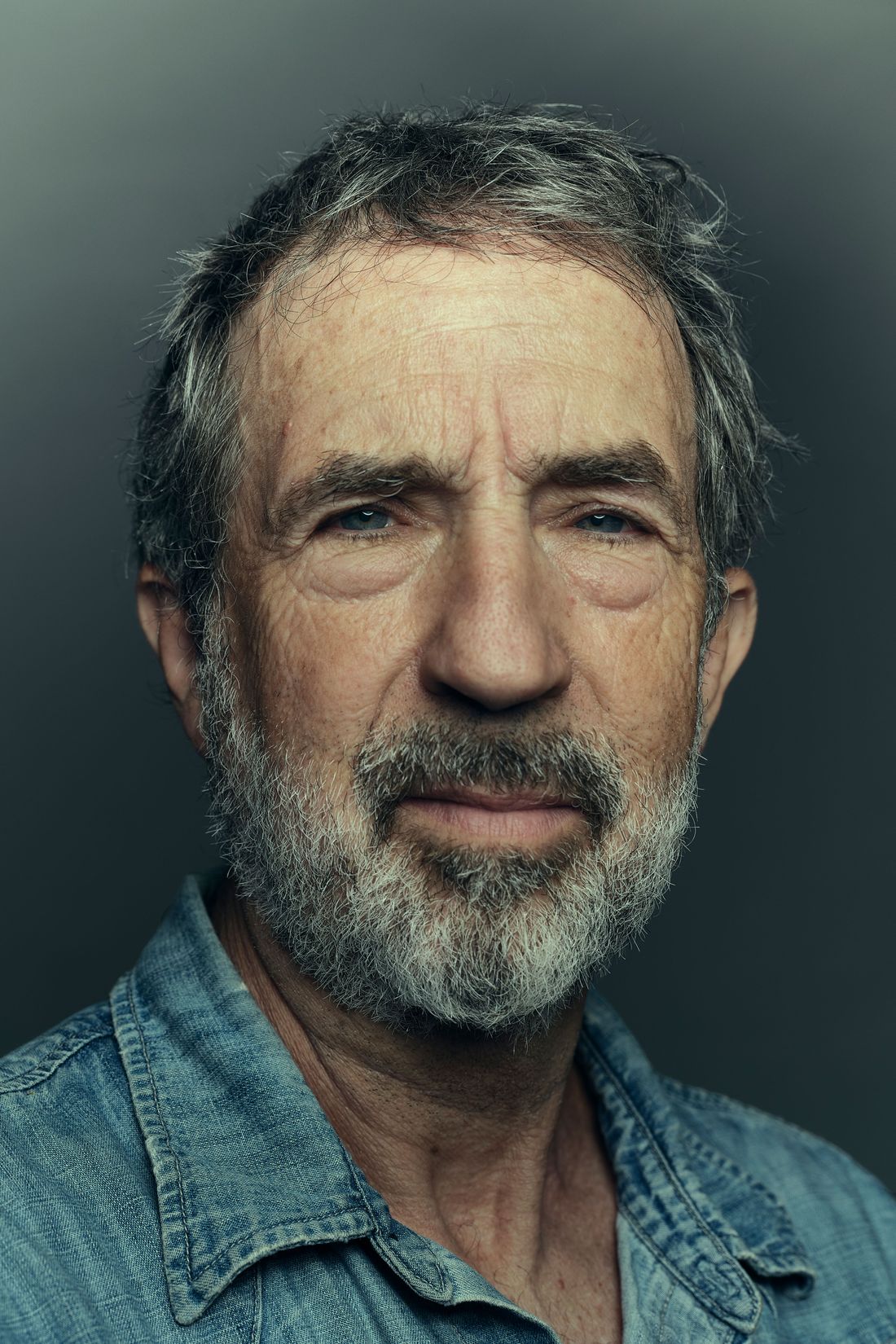

Goode, who’s wearing jeans, a blue T-shirt, and a face full of gray stubble, is moving slowly, still recovering from a left-hip replacement three weeks ago. (“I used to play a lot of street basketball,” he says.) He insists on giving a tour anyway. We climb into a Kawasaki utility vehicle, and he drives us around the property, which has been his primary residence since 2019. There’s the main house, guest bungalows, a tennis court, Japanese gardens, rock bridges, pools, and a giant mushroom sculpture by the German artist Carsten Höller. Goode first bought a vacation home here in 1989, and he’s been adding adjacent lots as they’ve become available. His compound now spans 100 acres.

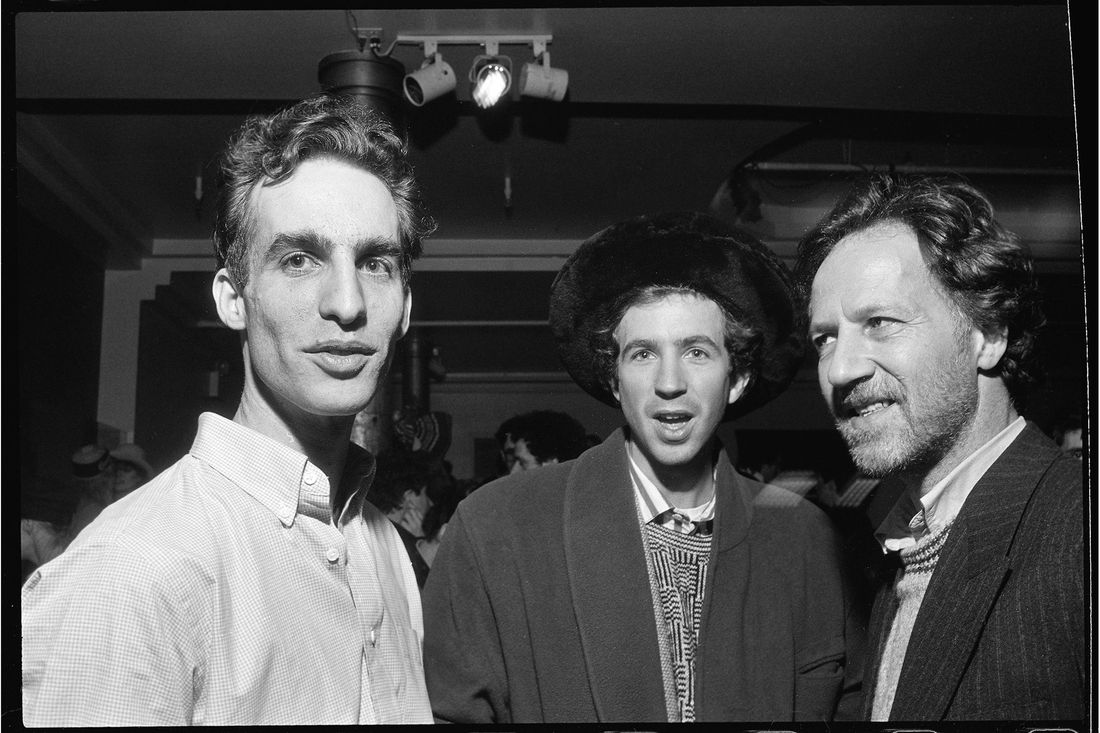

Goode, at 66 years old, entered filmmaking relatively late in life, having already found success in other professions. In the 1980s, he established a series of iconic nightclubs in New York City, with Area being perhaps the most famous due to its frequent redesigns every six weeks to suit various themes. For example, for “Suburbia,” Goode and his partners adorned the club’s entrance with a ranch house facade, while for “Science Fiction,” they constructed dioramas of alien landscapes and suspended a rocket ship above the dance floor, with artistic friends like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, David Hockney, and Jean-Michel Basquiat often contributing to the decor. Later, in the ’90s and 2000s, Goode expanded into opening upscale restaurants and boutique hotels across lower Manhattan, including Time Café, BBar, the Park, the Waverly Inn, and establishments like the Maritime, the Bowery, the Jane, and the Ludlow. These venues greatly influenced downtown culture during those decades, and some of them continue to attract celebrities and TikTokers today.

In a time when many in New York boasted the title, Goode was already a versatile creative director, specializing in multiple fields. His unique approach to hospitality, characterized by an auteur’s touch, transformed his venues into reflections of his artistic vision, even extending to the subtlest ambient elements. This approach not only made him financially successful but also gained him a modicum of fame. His romantic pursuits were diverse, spanning supermodels (Naomi Campbell, Rachel Williams), actresses (Julianne Nicholson), and many others. In his youth, he admits to harboring grand ambitions, believing himself to be a rock star.

In person, Goode is friendly but reserved. He listens as much as he talks — his resting facial expression is one of compassionate curiosity — which might explain how he gets so many of his documentary subjects to hang themselves. Friends describe him as shy, but then again, everybody I run into claims to be his friend, so he can’t possibly be that shy. In the two days I’m with him, he makes and receives phone calls constantly, usually on speaker, with everyone from the artist Tom Sachs to the primatologist Russell Mittermeier. “It’s a light shyness,” says the stylist Elizabeth Saltzman, whom Goode dated in the mid-1980s. (Now single and never married, he’s on remarkably good terms with many of his ex-girlfriends.) “He’s not scary or unapproachable. You can see it in his body language. He’s the ‘Oh, golly, me?’ guy.”

Essentially, Goode wouldn’t want to be perceived as a shark, despite his appearance occasionally resembling one. Back in 2019, mere months before the COVID-19 outbreak, he struck a deal with developers to demolish BBar and build a 22-story office building on its site instead. This deal, which includes a 99-year ground lease, starts him off with $125,000 per month. The building, named 360 Bowery, has recently been completed. Goode himself admits, “I’ve gentrified the once impoverished neighborhood.”

Currently, he’s producing films. Occasionally, these films turn out to be the most unexpectedly popular documentaries globally, while other times they remain personal projects with limited viewership. He recently showed me clips from three unfinished documentaries he is working on, one of which has already been bought by HBO, as well as a completed one titled “Wildflower“, which delves into his parents’ life and childhood in Sonoma, California. “I made that for my mom” – the environmentalist Marilyn Goode who passed away at 92 in 2022 – “as a way to make her feel appreciated during her later years, though I’m unsure if it will ever be widely distributed,” he explains.

Goode’s main interest, which seems to encompass all others, revolves around reptiles. This passion was ignited at the age of six with a pet tortoise and has grown since then. As he puts it, “I led two distinct lives. I could discuss contemporary art, business, fashion, and all the topics that are talked about in New York with people. But I could also converse about animals.” On his vacations, he would always seek out destinations with reptiles. Saltzman corroborates this: “He took me to Negril, and only later did I learn that it was because he wanted to search for Jamaican iguanas. He was certain he’d find one, even though they had been extinct since the 1940s. They were rediscovered later, in 1990, so he wasn’t entirely off the mark.”

Back in 2005, I founded the Turtle Conservancy, a sanctuary that took in over 250 rare tortoises displaced due to the closure of one research station at the Bronx Zoo. Since then, our numbers have grown significantly. Unlike Joe Exotic with his tigers, my focus here is different. The Turtle Conservancy isn’t open for public gawkers as you might expect from sensationalized roadside zoos like those depicted in ‘Tiger King.’ Instead, many of our residents were confiscated from illegal wildlife traffickers. Our ultimate goal is to reintroduce as many of these animals back into their natural habitats whenever possible. We’ve acquired approximately 100,000 acres of protected land globally for this purpose. I’m hopeful that the profits from the BBar land deal will ensure the continuation of my conservation efforts even after I’m gone.

Still, anybody who thinks this much about turtles must be at least a little touched. “It takes one to know one, and I do share some pathology with the crazier people in this world,” Goode says. “I can understand the feeling of wanting the animal that you can’t get.” Most of the Turtle Conservancy’s plowshare tortoises came from confiscations in China and Taiwan, but Goode tried without success to get some from Madagascar, too: “I gave the minister of the environment at that time a blank check that he could fill in, and he just wouldn’t do it. He could’ve written a million dollars in there if he wanted to.”

Goode’s reptile interests were his doorway into documentaries. He made nature shorts — The Argentine Tortoise, In Search of the Okinawa Leaf Turtle — and PSAs for the Turtle Conservancy to raise awareness of animal trafficking. Then he realized that some of those traffickers made pretty interesting subjects. Goode had once thought of his nightclubs, which attracted weirdos and squares alike, as venues for sneaking outsider culture into polite society. It occurred to him that docs might let him do something similar. “I’ve always been interested in the eccentric and looking under the rocks in places that don’t seem overtly interesting, beyond New York and L.A. That’s where you discover the Tonia Haddixes of the world,” he says. “Joe Exotic and chimpanzees could very well have been themes at Area.”

As a child in Sonoma, Goode dabbled in filmmaking by shooting Super 8 movies with his brother. Upon moving to New York, he took on various film-related jobs such as working behind the scenes for ‘Saturday Night Fever’, though he found these positions unsatisfying. He expresses this frustration saying, “I didn’t learn much about making films other than I didn’t enjoy it because I was mostly just sitting around.” Later in his career, he collaborated on music videos with Nine Inch Nails and Robbie Robertson. Despite having minimal experience in features, Goode felt no apprehension as he embarked on this new venture: “I never went to film school, but I didn’t go to culinary school either. Whenever I take on a project, I gather a team of like-minded individuals and we figure it out together.”

As a fervent admirer, allow me to highlight an exceptional individual named Goode. His skill in identifying talent is remarkable, often unearthing potential that isn’t immediately apparent from a candidate’s resume. The team working on his projects are versatile individuals hailing from diverse, non-traditional backgrounds.

In documentaries, having the knack to converse knowledgeably about exotic animals can provide unique access to otherwise inaccessible circles, according to Goode. He explains, “Navigating closed-off worlds is crucial in documentary making. The people who keep exotic pets are generally secretive and wary of three things: authorities, thieves who might steal their valuable creatures, and the media due to potential negative publicity.” Goode adds, “I’ve studied animals enough to establish a connection with them, which sets me apart.” Director Josh Safdie, who worked with Goode in the past, describes him as an expert herpetologist who is deeply passionate about his field. Safdie notes, “Goode’s knowledge and dedication made it possible for him to gain entry into that specific world. No one else could have done it.”

Goode has two additional advantages over most documentarians: time and money.

Over the last decade, the influx of investment from streaming services has significantly reshaped the documentary landscape. Numerous new players have emerged to cater to the escalating appetite for documentaries, leading to a focus on speed and quantity over quality. Consequently, many contemporary documentaries are hastily produced with minimal resources, frequently consisting of stock footage, brief introductory shots, and interviews that narrate events that have already transpired. There has been a decline in long-term projects that led to groundbreaking masterpieces like Hoop Dreams, American Movie, and Paris Is Burning. In their place, we see more celebrity memoirs (Beckham, Taylor Swift’s Miss Americana), reminiscent glimpses into the past (The Greatest Night in Pop, Brats), repeated examinations of crime cases (Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal, Conversations With a Killer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes), and recaps of events such as the Fyre Festival (Fyre, Fyre Fraud). As Goodes explains, “In essence, they’re pre-scripted because the makers already know the final destination before starting the production.”

2017 saw Goode being employed by CNN to develop and host a pilot for an animal-themed show. Since he had no experience in TV series production, they paired him with Left/Right, the company behind Showtime’s The Circus. However, Goode found their suggestions to be impractical and unhelpful. For instance, they suggested a segment about an animal attack and proposed interviewing a child who had been bitten by a pet iguana. Ultimately, they ignored this advice and found a man who had lost his leg to a tiger instead. Unfortunately, the pilot was not selected for further production. The challenging part was that CNN owned all footage shot, preventing its reuse. Fortunately, Goode knew he didn’t want to hand over any material related to Joe Exotic to them (Left/Right did not comment on this matter).

Currently, Goode’s method tends to be more conventional and significantly self-financed. He spends extensive periods shooting, focusing on subjects that pique his curiosity, and waiting patiently for a storyline to unfold. If something more captivating arises, he isn’t hesitant to adjust his plans accordingly. Approximately in 2014, while working on a documentary about reptile smuggling, he encountered a man from Florida transporting a snow leopard in a sweltering car. This encounter prompted him to shift his focus towards big-cat owners, and six years later, he released the critically acclaimed series “Tiger King” to the public.

According to Goode, he broadens his scope and focuses on the standout individuals in various investigations related to animal cultures over the past ten years. Some of these people include Ojai taxidermist Chuck Testa, deep-sea fisher Mark “the Shark” Quartiano from Miami, South African rhino breeder John Hume, and Heidi Fleiss, a former Hollywood madam who currently manages a parrot sanctuary in Nevada. While it’s uncertain whether these interviews will lead to something substantial, there’s usually a lot of unused footage in the process. Goode emphasizes that this isn’t a shortcut to wealth or a formula for success if you aim to establish a thriving production company.

Indeed, Goode’s own production company has thrived significantly. He admitted, “I knew Tiger King would perform well, but not to this extent.” The series was launched in March 2020, a time when many were confined to their homes due to COVID-19 restrictions. Netflix reported that a staggering 64 million households watched at least a part of Tiger King within its first month. This seemingly absurd figure is believable given the wave of memes, imitations, and Halloween costumes the show triggered. During a trip back from filming season two, Goode was stopped in Texas for speeding. The officer checked his details and then inquired, “Was it Carole who did it?”

The docuseries “Tiger King” had a profound impact on its subjects as well. Initially, many were thrilled by the attention and discovered methods to capitalize on it. However, over time, the chances dwindled, and resentment emerged among some cast members. They felt that the series depicted them as cruel animal abusers living in a polygamous, rural area. “Let me show you something pleasant,” says Goode. He shows me his phone, displaying a lengthy one-sided text conversation with James Garretson, the Florida Jet Ski entrepreneur who tipped off Exotic to the FBI. Garretson has repeatedly sent Goode the same image of a cartoon middle finger.

All of this animus made shooting Chimp Crazy more complicated. The community of private exotic-animal owners is small and tight-knit, and after Tiger King, Goode’s name was mud. So he came up with a workaround: He lied. Be warned: What follows is an account full of spoilers for Chimp Crazy.

For quite some time, Goode has been capturing footage of motherly monkeys, long before the popular series Tiger King. His fascination lies in their psychology. As Goode explains, “It’s largely about the self-centered desire for attention they receive when accompanied by a chimpanzee.” He notes that walking down the street with a human baby in a stroller wouldn’t garner as much attention as a chimp would. Yet, it also caters to their maternal instincts. Travis’s owner, Sandy Herold, acquired her chimp following the passing of her human daughter.

In 2021, the production of Chimp Crazy commenced with a trip to Pam Rosaire’s zoo in Sarasota, Florida. Rosaire, along with her sister Kay, manages Big Cat Habitat, a facility that has faced accusations of animal cruelty from PETA. Interestingly, they named their establishment to antagonize Carole Baskin, whose facility is called Big Cat Rescue and is located just under two hours away. Goode’s team was strategic in securing access to Rosaire, concealing their association with the creator of Tiger King. As they filmed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Goode wore a mask and hat, pretending to be part of the crew to avoid recognition. The filming session with Rosaire was successful, with her even revealing to the cameras that she once nursed one of her chimps. Impressed by this encounter, Goode decided to primarily focus on the culture of chimp mothers for his documentary.

Following my pursuit, the next subject of interest was Connie Casey, a breeder stationed in Festus, Missouri, who ran the Missouri Primate Foundation – once the leading provider of privately-owned chimpanzees across the United States. Her animals had a history of aggression; Travis was one I acquired from her in 1995, while another, Bo, infamously bit off her ex-husband’s nose. Casey was embroiled in a legal battle with PETA, who asserted that her apes were confined to tiny cages filled with their waste, living in inhumane conditions. In 2018, she attempted to quash this lawsuit by transferring the animals’ legal ownership to Tonia Haddix; however, PETA argued that this action made no substantial difference and merely added Haddix to the ongoing litigation.

55-year-old Haddix, with a blonde wig, is an animal trafficker, lacking formal training in husbandry. She refers to herself as the “Dolly Parton of chimps.” On Facebook, she markets her services and claims annual earnings of up to $350,000 by selling primates, marsupials, and various other creatures as pets. Liu comments that procuring these animals is complex and illegal. Haddix often sells to celebrities who, upon realizing the maintenance requirements, tend to discard their animals after a year or two.

Back in the 90s, Tonka, my beloved chimpanzee whom I cherish more than any human child, was a renowned actor, gracing the silver screen in movies like “George of the Jungle” and “Buddy” alongside Alan Cumming. By the time I adopted him around 2017, he had hung up his acting shoes and was no longer suited for domestic life. As I first met Tonka in 1996 when he was five years old, he was a sweet and gentle soul. However, during the press tour for “Buddy”, we were supposed to reunite on a morning talk show, but unfortunately, the trainer had to cancel his appearance. He warned me, “Tonka is now six, so he’s become sexually aggressive. There’s a high chance he would try to court you live on television.”

Goode thought it unlikely that Casey and Haddix would talk to him directly, so he resorted to using another strategy: He decided to hire someone else to approach them, pretending to be making the film. In his book “Chimp Crazy,” Goode refers to this position as a “proxy director,” but in essence, it was similar to being a spy.

In this scenario, Goode found the ideal person for the task at hand – Dwayne Cunningham, a friendly ex-circus clown from Ringling Bros., who had collaborated with the Rosaires at the Big Cat Habitat and served time for smuggling reptiles. Although they don’t share the same perspective on owning exotic pets (Cunningham advocates for it, especially chimpanzees, under the condition that animals are treated kindly and housed with other primates), Goode sought out Cunningham due to his relevant background. However, it is important to note that while Cunningham has experience in entertainment, he lacks formal filmmaking expertise – his closest connection to journalism being his father’s profession as a newspaper printer.

In the vibrant spring of 2021, I found myself sharing a breakfast table with Haddix, Cunningham, and Liu at a cozy Holiday Inn Express. At that time, Haddix was residing in a hotel, and her room was a bustling zoo of sorts, filled with visiting spider monkeys, kangaroos, and an array of other extraordinary creatures. As Liu recalls, “Her room was a revolving door for animals.”

In the film “Chimp Crazy”, Goode openly addresses and struggles with many of these deceitful situations, and a significant part of its tension arises as the deception slips from his grasp. As Goode puts it, “We used Dwayne to initiate conversations with Tonia, but we never anticipated he would take over the discussion as much as he did.”

Back in June 2021, PETA secured an order to have seven chimpanzees housed at Casey’s facility, including Tonka, taken away by federal marshals and transported to a Florida wildlife sanctuary. Haddix informed the media that her chimp wouldn’t be making the journey – he had passed away from heart failure the preceding month, and she had cremated his remains in her backyard fire pit. However, people didn’t believe her account. “We knew she was lying,” states McBride. “It was just difficult to provide evidence at the time.” In February 2022, PETA put forth a $10,000 reward for any information leading to Tonka’s recovery.

Indeed, Tonka was very much alive, but in a state of confinement in Haddix’s basement in the Ozarks. In January 2022, Haddix had invited Cunningham and her film crew to her home for a Zoom court appearance. On oath, she emotionally recounted discovering Tonka deceased. Later, she guided Cunningham to her basement where the chimpanzee had been housed in a compact enclosure. McBride recalled, “We asked, ‘So where’s Tonka?’ She replied, ‘Oh, he’s here. He’s been right below where we’ve been for the past five hours.'”

Haddix claimed Tonka was happy. In the doc we see him eat McDonald’s, drink soda, and play with a tablet computer. Goode consulted with experts, showing them footage of the chimp and asking them to analyze his body language. “When we saw Tonka in that cage, he was rocking back and forth,” says Goode. “That tic is what happens when chimps are held in captivity. It’s what they do when they’re bored out of their minds, and it was an indication to us that he shouldn’t be there.” Craig Stanford, a USC primatologist who worked with Jane Goodall, concurs: “We don’t see this in the wild, but in zoos, chimpanzees do all this neurotic stuff, including rocking. We might call it clinical depression.”

At approximately the same period, Goode observed some unusual behavior from his proxy director. Was it possible that Cunningham had become a double agent? “He and Tonia grew exceptionally close,” Goode explains. “They were constantly in contact outside of our view. She confided in him things she didn’t share with anyone else, and he would tell her secrets we weren’t privy to. Dwayne and I had some heated exchanges because his allegiance seemed to favor Tonia, and he was essentially deceiving us. I would wager that Dwayne knew about Tonka’s survival before we did.” (Cunningham disputes this: “I found out after the video call with the judge.”)

Ultimately, Goode, along with his team, and even Cunningham, made the choice to intervene on behalf of Tonka. “There’s a recurring dilemma when people unlawfully keep animals,” Goode explains. “When you have a chimpanzee, there are limited choices. You can attempt to pass it off – give it to someone else who owns chimps and hope nobody discovers it’s that particular chimp – or you can euthanize it.” They reported their findings to PETA, and in June 2022, Tonka was rescued from Haddix’s basement.

Despite the documentary team apparently exposing her, Haddix seemed unaware of this initially. During Tonka’s removal weekend, she invited Cunningham to her home. According to Goode, Jeremy warned, “Under no circumstances should Dwayne enter that house. There’s no way we can risk him walking into a trap.” Yet, Dwayne felt at ease, so they decided to trust his intuition. Cunningham concealed a camera and, in a twist reminiscent of the film Serpico, visited Haddix. McBride finds it surprising that this footage shows everyone else in the house is aware Dwayne was the informant, yet Tonia refused to accept it.

A few days passed, and Haddix received a call from a reporter from Rolling Stone. The journalist had found out through court records that Cunningham was the informant, and he was working for Goode. Haddix informed the magazine that she would never have collaborated on the documentary if she’d known Goode was involved, and she vowed to prevent its release. “I’m going to halt that production,” she declared.

Initially, Haddix continued conversing, initially with Cunningham, later shifting to Goode. In the end, it was Goode who interviewed Haddix numerous times over a period of one and a half years. “Tonia and I actually developed a friendship,” shares Goode. However, he is quick to add, “I shouldn’t boast too much about this. It turned out that she is open to discussing her case with anyone.”

In a different way, Haddix describes her connection with Goode as something beyond friendship, stating, “We’re not friends, and he’s aware I don’t care for him.” She shares that she has mostly come to terms with the past events and acknowledges some fault. (In her own words, “Yes, I lied under oath to a federal judge, and it’s something I’m not particularly proud of.”) However, during our conversation, Haddix mentioned that she had recently watched an interview with Goode on the Today show and felt disrespected. “I was only going to give a neutral review, but then he spoke negatively about me on live television.”

Haddix reveals that upon discovering Goode was making the documentary, she sought legal advice regarding an injunction. However, no one was willing to take on the case due to PETA’s involvement and Carole Baskin’s lawsuit to halt Tiger King’s second season. Baskin sued Netflix in 2021 over footage of them appearing in the second season, arguing they had only agreed to be part of the first season. The lawsuit was later withdrawn. Haddix explains that despite her hopes, speaking with the production team didn’t result in her seeing Tonka again.

Currently, Tonka resides at the Save the Chimps sanctuary located in Fort Pierce, Florida, which spans over 150 acres. This haven is home to more than 200 chimpanzees who coexist in various groups on a dozen individual islands. Not long after Tonka’s arrival, Cumming paid a visit and shared his impression: “There’s an enchanting quality about their having their own islands and living together in tribes.” He continued, “The chimps at this sanctuary are cared for and cherished, yet they have the freedom to roam freely and behave as wild animals. Tonka appeared to be thriving, healthy, energetic, and content.”

As a devoted admirer, I can share that Goode yearned to conclude “Chimp Crazy” with Haddix and Tonka reunited, but PETA and Save the Chimps refused. He expresses, “They view her as the devil.” In my opinion, she’s likely never witnessed a primate in the wild, and it would be incredibly beneficial for her. One could hope that she might grasp the atrocity of her actions. However, it’s simple to condemn Tonia from a distance. If you spend time with her, it becomes challenging not to like her, and we found it difficult to turn against her. I fervently pray that she gains something positive from this experience, and that the outcome justifies our actions.

Previously criticized for being too entertaining, the series “Tiger King” managed to create a significant impact on its core issue, animal welfare. Some critics found it exploitative and sensationalist, while animal-welfare groups felt that its message about conservation was lost amidst its unexpected plot twists. Despite these concerns, the show’s immense popularity, including being instrumental in bringing the Big Cat Public Safety Act to the Senate floor, led to real change. The bill, which effectively banned unlicensed roadside zoos like Joe Exotic’s, was passed in 2022. As the creator of the series, Goode acknowledges that it received a lot of criticism for not focusing enough on the cats, but he believes that ultimately, it made a substantial contribution to improving animal welfare conditions.

The lesson from the show “Chimp Crazy” becomes more understandable, but here’s a reminder just in case: THE FEDERAL LAW STILL DOESN’T PROHIBIT PRIVATELY OWNING CHIMPANZEES. Goode expresses that he isn’t advocating for animal policing or being like PETA, but he believes children in America could enjoy a pet bearded dragon or rosy boa. However, regarding chimpanzees as pets, his stance is clear: they are not suitable pets due to their problematic nature.

Currently, there’s a popular trend of heartwarming nature documentaries that tug at your emotions, as he points out, using the example of the Oscar-winning 2020 documentary “My Octopus Teacher” and the 2022 film “Wildcat,” which focuses on a British war veteran’s bond with an ocelot. However, this may not appeal to someone like him who resides in New York City, as he seems uninterested. He prefers documentaries that cater to a wider audience rather than those that only resonate with people already knowledgeable about the subject matter. In his opinion, talking exclusively to individuals who are already familiar with an issue doesn’t have much impact.

Read More

- Hades Tier List: Fans Weigh In on the Best Characters and Their Unconventional Love Lives

- Smash or Pass: Analyzing the Hades Character Tier List Fun

- Understanding Movement Speed in Valorant: Knife vs. Abilities

- Why Destiny 2 Players Find the Pale Heart Lost Sectors Unenjoyable: A Deep Dive

- W PREDICTION. W cryptocurrency

- Why Final Fantasy Fans Crave the Return of Overworlds: A Dive into Nostalgia

- Sim Racing Setup Showcase: Community Reactions and Insights

- How to Handle Smurfs in Valorant: A Guide from the Community

- PENDLE PREDICTION. PENDLE cryptocurrency

- Brawl Stars: Exploring the Chaos of Infinite Respawn Glitches

2024-08-26 16:57