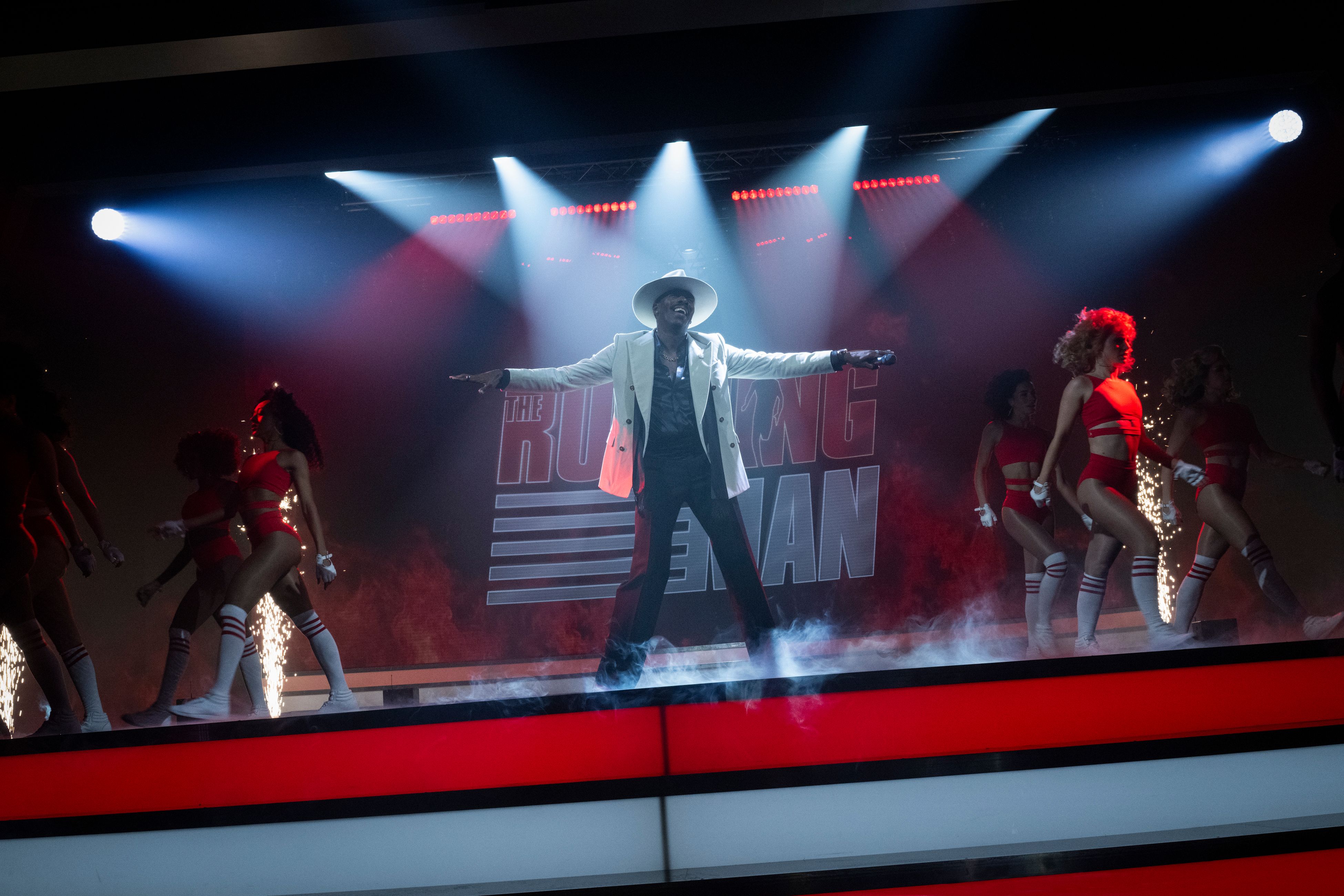

Edgar Wright’s The Running Man isn’t a remake of the 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger film; it’s actually based on Stephen King’s 1982 novel (originally published under the name Richard Bachman). While fans of the movie might care about this difference, it’s important because Wright’s version brilliantly combines King’s original story with his own energetic and inventive style. The result is a film that’s quick, unpredictable, sharply humorous, and constantly moving.

This is Edgar Wright’s largest film project so far—a true blockbuster produced by a major studio. He says the challenge was made easier because Paramount Pictures not only supported the idea but also gave him a lot of freedom creatively. As Wright explains to Ebaster, he was able to stay true to his vision. “We really got to make the movie we wanted to make,” he says.

Throughout his career, Edgar Wright has consistently demonstrated a unique ability to blend creative vision with the specific demands of each film. From his early comedies like Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, to his adaptation of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, he’s always felt like a director with a distinct style. Films like The World’s End, Baby Driver, and Last Night in Soho stand out as personal projects, feeling crafted with care rather than dictated by studio expectations. Even with a larger-scale film like The Running Man, that same artistic sensibility shines through, showing he’s a filmmaker who both has a strong vision and knows how to tailor it to each story.

Before the release of his new film on November 14th, Edgar Wright spoke with Ebaster about his career as a director. They didn’t just discuss how he got to making The Running Man, but also what he’s learned and how he’s grown creatively, from his early work on shows like Spaced and movies like Shaun of the Dead to his current projects.

As I understand it, the project began in 2017 when you publicly announced your intention to turn this book into a film on social media.

Someone asked me on Twitter which movie I’d remake, and I just gave an answer – it wasn’t a formal announcement about a project I’m working on.

When I first heard about this film, I was really curious about how much the initial ideas connected with what was happening in politics at the time. It was fascinating to learn how those original concepts either stayed true to that connection, or actually grew to reflect current political events as the project developed. I was interested to see how much the film’s vision changed – or didn’t – as it took shape.

I believe the connection lies in how ideas develop over time. Stephen King wrote his book in 1972, but it wasn’t published until 1982. He chose the year 2025 as the setting simply because it sounded good—he didn’t anticipate we’d be discussing the book in 2025.

When did you first discover the book?

I first read Stephen King’s The Running Man when I was around 14, back in the late 1980s, and it stayed with me. When I saw the 1987 film starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, I immediately noticed how different it was from the book – it only used a small part of the game show concept. As a Stephen King fan and someone starting out as a filmmaker, I always thought there was a much better movie to be made from the book. I even looked into getting the rights to adapt it about 15 years ago, but they were too complicated and weren’t available, so I eventually put the idea aside.

What changed?

I often get asked in interviews which film I’d remake, and I always say The Running Man. It was a coincidence that, shortly after, producer Simon Kinberg contacted me to say they’d just acquired the rights to the story. My co-screenwriter, Michael Bacall, and I started working on a script in early 2022. Then, the writers and actors strikes hit in 2023. Interestingly, Mike Ireland from Paramount suggested in early 2024 that we should actually make the film this year. It wasn’t because the story is set in 2025, but it’s a remarkable coincidence that we’re now six weeks away from the end of 2025, releasing a movie set in that same year.

I was really curious about how the filmmakers approached the book’s 2025 setting. Considering it’s a dystopian story, I wondered what choices they made to build that future world and how they envisioned things unfolding from that starting point. It felt important to understand how they translated the book’s timeframe into the visual and thematic reality of the movie.

The film deliberately avoids stating a specific year. Director Wright explains that many sci-fi movies don’t project far enough into the future, leading to a sense of letdown when the predicted year arrives – like with 2001 or Escape from New York. Instead, they aimed for a ‘different tomorrow,’ a retro-futuristic aesthetic similar to Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, which blends 80s filmmaking with 40s design. The production design, led by Marcus Rowland, was based on the idea of what Stephen King envisioned in 1982 as the year 2025. This approach allows for both advanced and regressed technologies, creating a unique and believable future.

This film’s humor feels very similar to your previous work, but it seems to be reaching a wider audience. Could you talk about how your usual creative approach met the expectations of making a more popular, big-budget movie?

I’m really glad this film is being made by a major studio because I never felt pressured to change my artistic vision. We were just able to create the movie we set out to make.

Considering your work on films like Ant-Man, and perhaps even Tintin, have you gained any insights into managing the demanding and critical nature of big-budget Hollywood filmmaking?

The Marvel process was unique because I wrote the first draft before the first Iron Man even came out. By the time they started making it, the franchise had an established brand, continuity, and a specific style, which was different from my original vision. Luckily, the people who hired me also wanted my take on the story. We also needed Stephen King’s approval, which was nerve-wracking – waiting to see what he thought of our adaptation. Thankfully, he loved it! But that created a new pressure – not only did I want to create the movie I envisioned, but also the movie he envisioned. Throughout production, my main goal was to make sure Stephen King was happy, and thankfully, he is – and that’s all that really matters to me.

Before we got the green light, Michael and I really wrestled with how to bring Stephen King’s vision to life while still making it our film. It was a challenge finding that sweet spot where we honored his source material but also injected our own style and interpretation. We spent a lot of time figuring out how to balance those two things!

A lot of what goes into filmmaking happens instinctively, not through careful calculation. I don’t deliberately break down how much of a film is influenced by the studio, the source material, or my own style. It just evolves naturally into the movie I envision. I’m really happy that the film audiences will see is the one I set out to create.

I’ve always been really impressed by the careful detail in your earlier work. Could you talk about how your approach to design and creativity has changed over time?

For me, designing a film often feels like a necessity – you have to be resourceful. Shaun of the Dead is a great example; it was made on a tight budget, but we aimed high. The only way to achieve something ambitious with limited time and money is to over-prepare. I always try to be open with my crew and share as much information as possible, because I believe a fully invested team produces the best work. This project was the same. Plus, we had a fantastic source material – the book was incredibly detailed, and we built upon that foundation.

Someone brought up Shaun of the Dead earlier, and it got me thinking. Because Simon and I have had so much success together, people seem to see our partnership like the one between Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson – a really consistent, fruitful creative connection. Now I’m working with Michael, and it’s fantastic. It makes me wonder, though, how hard it is to actually find those people – the ones who just get what I’m trying to do and can collaborate on that level. It’s not always easy, is it?

I’ve been fortunate to work with great collaborators throughout my career. When you enjoy working with someone, you naturally want to continue that partnership – Simon and Nick are perfect examples. People like Nira Park, Marcus Rowland, and Paul Matchless – who I’ve worked with since Spaced – are relationships built over many years. When Simon Kinberg approached me about the book, Michael Bacall was the first person I called. Despite being known for comedy, I felt his skills were a perfect fit for this project, given its sci-fi, satirical, and political themes. Making a complex film with a tight deadline would be much more difficult if I had to work with an entirely new team. I don’t believe in doing everything myself; I thrive on collaboration. It’s wonderful to repeatedly work with people I trust and admire.

In what ways have your professional relationships helped you develop as a filmmaker or simply allowed you to keep working in the industry?

Edgar Wright emphasizes how essential Nira is to his work, calling her his closest collaborator since they first worked together on Spaced. He believes it’s crucial to bring trusted colleagues from your beginnings when moving to a new environment like Hollywood. He’s noticed directors who come to Hollywood without their original team often struggle because they lack support and can be easily overwhelmed. It’s not just about loyalty, Wright explains, but about consistently working with people you have a strong, successful creative partnership with.

You know, it’s funny, people used to introduce me as an English director working in Hollywood, almost like an outsider. But honestly, after years of being here, working with so many incredible people, I really feel like I’m part of the Hollywood community now. It doesn’t feel like ‘coming to Hollywood’ anymore – it just feels like home, and I’m one of the folks who makes movies here.

That’s a tough question. It’s interesting that since Shaun of the Dead came out 21 years ago, the idea of making movies in Hollywood feels a bit outdated, because very little is actually filmed there anymore. Plus, I think filmmaking has become more global in the 21st century for various reasons.

I remember how personal The World’s End was for both you and for Simon.

We couldn’t reveal it then, but I was genuinely impressed with how Simon spoke about it.

It’s beautiful that you guys were able to exorcise and explore those personal experiences.

You know, as a lifelong moviegoer, I’ve always felt there’s something very British about avoiding direct emotional expression. It’s like we’d rather explore those feelings through a film – create a story about it – than actually have a raw, honest conversation with each other, especially between men.

Throughout your career, to what extent have your own life experiences and interactions with the world fueled your creativity, compared to simply aiming to entertain or provide an escape for people?

It’s a combination of things. People often assume there’s a deliberate, overarching message or theme in my films, which is amusing. I recall Simon once mentioning the ‘Cornetto trilogy’ and suggesting they were all about the individual versus society. It struck me because he’d never expressed that idea before! He was right, but it wasn’t a planned theme, and it definitely wasn’t intended as a trilogy. Sometimes, it takes an outside perspective to define what a film is about. I often feel like I make movies so the audience can explain them to me. For example, someone tweeted a brilliant interpretation of ‘Last Night in Soho’ – they said it was a horror film about the disappointment of meeting your heroes. It perfectly captured the film’s essence, and I immediately started using that description in interviews!

To help encourage deeper self-reflection, do you ever consciously think about what people expect from you, and then decide whether to meet those expectations or go in a different direction?

I believe in giving audiences what they truly need from a film, not just what they think they want. It’s a delicate balance – often what people expect from a movie differs from what the filmmaker intends. I’ve seen projects where fans desperately ask for something, only to be disappointed when they finally get it. It’s a constant challenge. My approach is to create the kind of movie I, as a viewer, would absolutely love. Of course, test screenings are crucial – you need to see the film through the eyes of a general audience. Those screenings can be hit or miss, but I haven’t reached a point in my career where I can simply create a film and not worry about how it’s received.

Has your approach to directing evolved over time? In your earlier films, you had a very distinct style. Are there any elements of that style you’ve moved away from, or that you no longer enjoy using?

Director Edgar Wright believes it’s easy to fall into repeating yourself creatively, like doing a cover of your own work. He points out that even in his films like the Cornetto trilogy and Scott Pilgrim, stylistic choices like fast cuts and montages can become stale after a while. What he appreciated about adapting The Running Man was the opportunity to create a truly immersive experience. The original novel kept the story entirely from the protagonist’s perspective, making the reader feel like they were in the game show alongside him, and Wright wanted to recreate that feeling in the film through the action and visuals. He emphasizes the importance of challenging yourself as a director, arguing that becoming complacent is creatively fatal. A director should always feel a bit scared or uncertain about a scene. With a project as ambitious as The Running Man, Wright says he felt that nervous energy every single day on set.

Early in your career, you were known for playfully referencing other films and art in your work – viewers enjoyed spotting those connections. Has your creative process evolved to the point where you feel less need to explicitly showcase those influences?

Wright feels it’s important not to make audiences feel like they need to prepare before seeing a film. He recalls getting interview requests asking what films people should watch before seeing ‘Last Night in Soho,’ and his reaction was that ideally, none are needed. He doesn’t want viewers to feel like they have to do ‘homework’ – like watching a previous adaptation or reading source material – to enjoy the movie.

Some are calling this a remake, but it’s more like another adaptation of the original story – perhaps the second or third, following ‘The Adventures of Tintin’. Has this success made you more interested in adapting other books rather than coming up with completely new ideas?

I approach each project individually. When I first received the script for Scott Pilgrim, I hadn’t read the book before – it had only recently been published, as I recall. It’s a story that really stuck with me from my youth. It’s unusual to be offered a project you genuinely wanted to work on, but that happened with Scott Pilgrim. I enjoy the variety of working on both original stories and adaptations. A great thing about Scott Pilgrim was having Bryan Lee O’Malley on set, and thankfully, both authors were still around to talk to. Stephen King was pretty hands-off during filming, but we honored him by naming a diner in the movie after his wife, Tabby’s Diner. I sent him a photo of it at 5 a.m., and he loved it – that was probably the only email I sent him during the shoot. Sometimes, having a particularly good experience can be a bit of a double-edged sword. That’s how I feel about making The Sparks Brothers – I’d love to do another music documentary, but Ron and Russell Mael were so fantastic to work with, they might have spoiled me for any other musical subject.

I’ve been thinking about your career lately, and I’m really curious – when you first started directing, did you imagine it would unfold like this? Not just the sheer number of films you’ve made, but also the kinds of stories you’ve chosen to tell? It’s amazing to see everything you’ve accomplished, and I wonder if it aligns with your original vision.

I’m truly thankful to be working, especially in this challenging industry. So many talented people are struggling to find projects, and I don’t want to take my opportunities for granted. It’s incredibly rewarding to have made this film, and even more so to have provided work for artists, both as a director and a producer, particularly after the recent strikes. I never want to take that for granted. I approach every film as if it could be my last, so I always put in my best effort and take pride in the work, because you never know what the future holds.

Considering your involvement in several projects like ‘Barbarella’ recently, how dedicated are you to a single project at a time when you’re working?

As a film enthusiast and someone who’s been deeply involved in making movies, I can tell you that once you’re actually in production, everything else fades away. It completely consumes you. This last project was intense – seriously, a year of working six or seven days a week, often sixteen hours a day! So when people ask me what I’m doing next, my honest answer is usually just, ‘sleeping!’ But honestly, choosing the next film isn’t always about what I want to do first. It’s about timing – finding the perfect actor, getting the budget right, and even things like tax incentives. It’s a whole puzzle. Right now, I’m just focusing on recovering, and then I’ll start thinking about what story I want to tell next.

Considering movies have been released every four to five years recently, are you happy with that schedule?

I’m always eager to work on more projects, but a lot of things can affect whether a movie actually gets made. There’s the script, the development process, and even things like strikes. I once started working on a film that fell through – it just wasn’t the right moment, the right cast, or the right budget. I have to give credit to Mike Ireland, who was head of Paramount at the time, for really pushing to get The Running Man made. It’s rare for a project to get a quick start, so it was great when someone finally gave the go-ahead. It’s funny, because after finishing a film, you always think you’ve assembled the perfect team and can jump right into the next one, but it never happens that smoothly. People move on to other things, or you have to start writing a new script. I admire filmmakers like the Coen Brothers, who managed to make a movie every year, but then I remember there were two of them!

Read More

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- Gold Rate Forecast

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- The Abandons: Netflix Western Series Disappoints With Low Rotten Tomatoes Score

- EUR INR PREDICTION

- 2026 Upcoming Games Release Schedule

- Train Dreams Is an Argument Against Complicity

2025-11-11 22:26