2001: A Space Odyssey, the 1968 sci-fi classic directed by Stanley Kubrick, remains an iconic piece in the annals of cinema. Kubrick’s filmography boasts masterpieces like Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket, and more, but 2001 stands above the rest. It is frequently hailed as Kubrick’s grandest work. Known for his grandiose approach to filmmaking and penchant for tackling provocative themes, Kubrick delved into stories that defy time and explore the essence of humanity on a cosmic scale with 2001: A Space Odyssey in particular.

This film, undeniably, left a lasting impression on numerous filmmakers who emerged in the subsequent decades. For instance, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Christopher Nolan are among its admirers. Spielberg himself referred to it as the “Big Bang” for his generation of filmmakers. However, it wasn’t universally appreciated; some found its portrayal of humanity’s past, present, and future disquieting. Andrei Tarkovsky, a director renowned for his masterful science fiction works, was one of its detractors. Regardless, there’s no denying that the film elicits intense reactions from those who watch it.

2001 Exposes Violence in the Evolution of Humankind

Kubrick Connects the Dawn of Humans With Artificial Intelligence

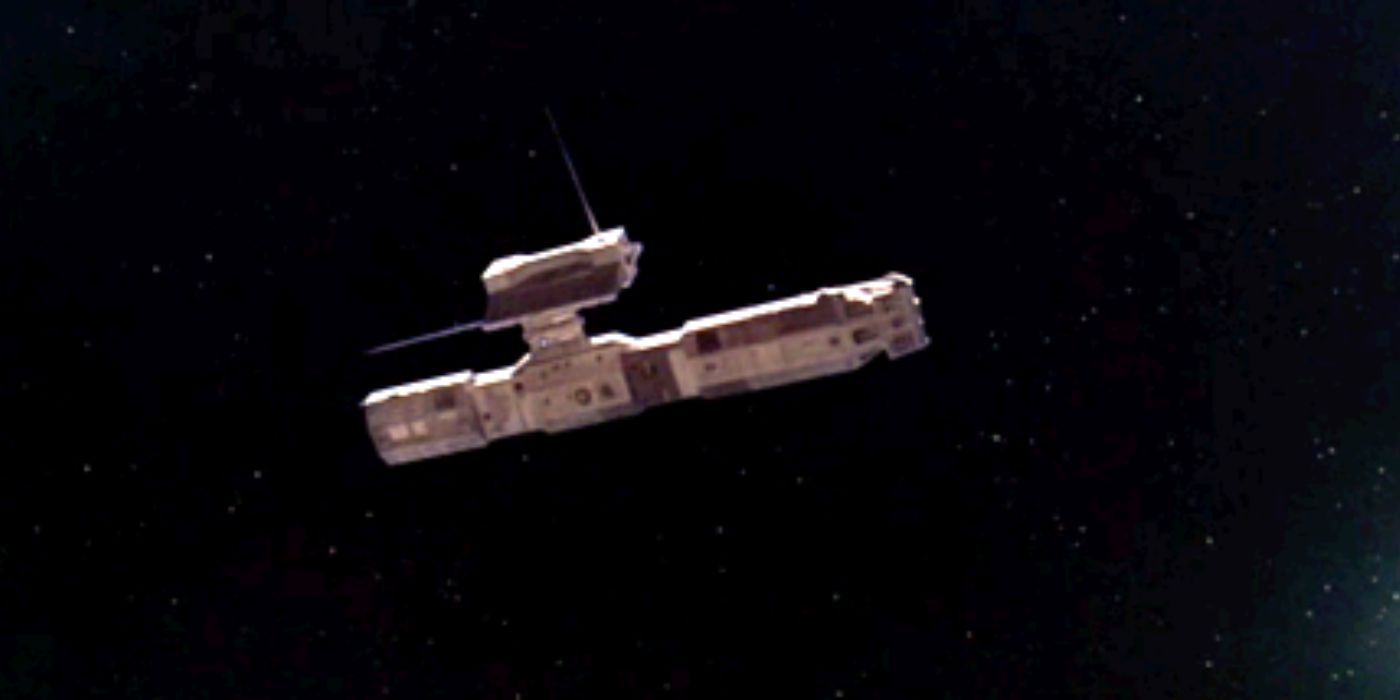

1968 marked the release of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” a film that remains intriguing as its meanings evolve with time. Co-written by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick, the movie aims to narrate a story transcending temporal boundaries, delving into the poignant theme of progress’s tragedy. The Space Race was nearing its climax when the film debuted, only months before the Apollo 11 mission touched down on the Moon. Unlike many American filmmakers during that era, Kubrick chose not to portray space exploration as an optimistic or jingoistic theme in his work. Instead, Kubrick’s sci-fi leans more towards Soviet ideas of form and content compared to conventional Hollywood narratives.

The groundbreaking Soviet Montage Theory, devised by filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein during the 1920s, significantly transformed global cinema as we know it today. Although Stanley Kubrick was usually secretive about his inspirations, he openly acknowledged Eisenstein’s impact on his creative process. This influence is particularly noticeable in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film where editing plays a pivotal role in shaping the narrative. The film’s central theme revolves around the exploration of violence and its impact on human evolution, with the storyline often de-emphasizing human agency, marking a stark contrast to the heroic narratives and technological optimism commonly seen in American mainstream cinema. However, Kubrick’s interpretation of this genre doesn’t entirely align with Soviet cinema, especially politically. Instead, it finds itself in a neutral political space, a characteristic that remains common in contemporary arthouse American cinema.

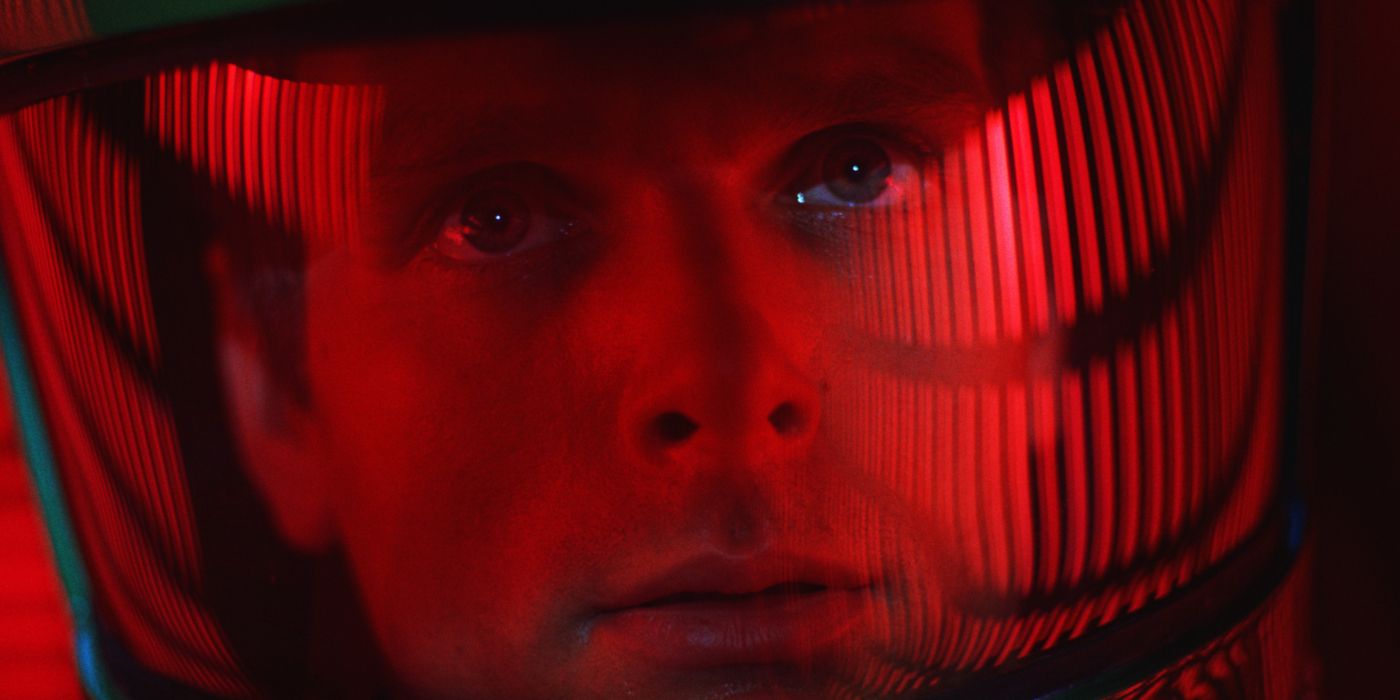

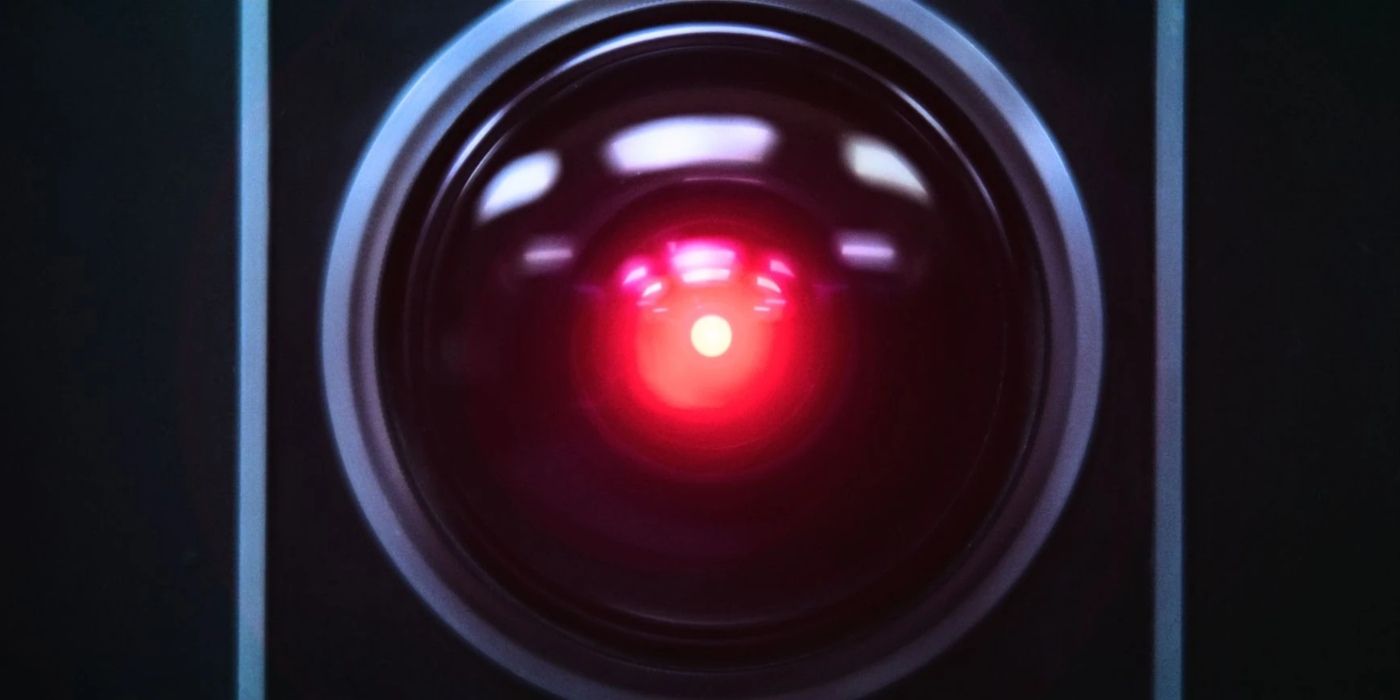

As I delve into the timeless masterpiece that is Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, I find myself marveling at how its narrative of life’s cycle mirrors my own evolving understanding of the film. The rapid advancements in technology have transformed our world so profoundly that revisiting HAL 9000 today offers a fresh perspective.

Geoffrey Hinton’s stance on AI today underscores Kubrick’s vision as more prescient than we initially thought, hinting at a reality where the line between man and machine blurs even further. Intriguingly, some speculate that the mysterious monolith in 2001 may have seeded our Collective Unconscious, leading to the creation of modern devices like iPhones and other “black monoliths.” This theory ties 2001 to the darker side of technology explored in shows like Black Mirror.

The monument, often perceived as the mystical embodiment of advancement during periods of power, might symbolize the enigmatic human instinct to resolve issues through violence. In the Dawn of Men series, it may appear as a symbol of human curiosity: the alluring and intimidating void of the unknown. However, its meaning deepens significantly when an ape’s bone transforms into a spaceship in what is considered one of cinema’s most memorable transitions. Whenever the monument reappears, it underscores the notion that our evolution is deeply rooted in violent dominance, and that every tool we create is designed for harm or destruction. In this context, our progress can be seen as a constant cycle back to nature.

2001 May Be the Movie That Aged the Best in History

The Story and Themes Remain as Timeless as the Music and Visuals

The monolith’s influence draws a comparison to the addition of “Space Odyssey” in the title, as Kubrick portrays the Space Race as similar to Odysseus’ journey after the Trojan War in Homer’s Odyssey. Just like Odysseus’ voyage, an odyssey is not just a long journey home; it’s also a profound spiritual and existential exploration that occurs alongside physical travel. In this journey, monsters symbolize the ongoing struggle for peace. Interestingly, both the Odyssey and 2001 present a paradox: humans yearn for peace, yet they often seek it through violence and deceit. This parallel becomes evident when considering the atomic bombs dropped by the United States on civilians towards the end of WWII and during the Cold War, events that Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke perceived as reflecting the Western mindset akin to the Odyssey.

The controversial ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey reinforces Stanley Kubrick’s theme of technological pessimism – just as dinosaurs once roamed the earth before apes, something else will come after us. The scene where the monolith is seen from the ground in The Dawn of Man suggests a new chapter for humanity. This new beginning, however, is an illusion created by our relentless chase for the unobtainable through technological advancements and displays of power.

The film 2001: A Space Odyssey presents an intriguing paradox – it shows a pattern in the cosmos while depicting life as chaotic. To emphasize this paradox, Kubrick uses perfectly symmetrical visuals alongside deeply moving music. This paradox, which appears to be a contradiction, is actually just a question of perspective.

The film’s visual elements often receive attention, but its significant use of music is frequently overlooked in discussions. Music plays a crucial role in Stanley Kubrick’s films, serving diverse purposes in each movie. The song “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” composed by Richard Strauss in 1896, is recurrently used in Kubrick’s works, including 2001. This piece serves as a bold nod to Friedrich Nietzsche, whose book Thus Spoke Zarathustra influenced key concepts like Übermensch, nihilism, and eternal recurrence, which are all evident in the narrative of 2001. Even for those who may not recognize this reference during viewing, the powerful and timeless nature of such music effectively conveys the wide-ranging emotions essential for telling a profound story.

1960s-made science fiction remains strikingly futuristic due to its aesthetics, thematic elements, and thought-provoking references that continue to be relevant in discussions about how ideologies develop within artistic contexts.

2001 Had an Impact on Christopher Nolan and Other Creatives

Movies Like Inception and Interstellar Reflect Kubrick’s Influence

In our previous conversation, it was mentioned that the impact of “2001” goes beyond just art, influencing various fields and sparking creativity in many generations. However, this influence wasn’t always positive; it even motivated Andrei Tarkovsky to create an antithesis to “2001”. His disdain for Stanley Kubrick’s interpretation of the genre was so intense that he felt compelled to produce “Solaris” in 1972. Even if Tarkovsky hadn’t openly criticized Kubrick’s film, it would have been evident that “Solaris” was a counterargument to “2001”. Tarkovsky despised how Kubrick simplified human nature into technological advancement. Kubrick’s preoccupation with cosmic truth, as if life were a monolith, overlooked the importance of identity, trauma, and memory, themes that are prevalent in Tarkovsky’s work.

Most science fiction filmmakers globally consider 2001 as one of the genre’s finest, and so does he. Just as seeing Solaris without its historical background alters the experience, Nolan’s films share a similar quality. In both cases, Nolan delves into the idea that reality is multilayered, with the innermost layers only accessible to select characters. His method of crafting grand sci-fi tales can be likened to reimagining 2001 as a potent narrative blueprint.

In an article for Indie Wire, Nolan ranked his top films, placing “2001: A Space Odyssey” at the first position. The runner-up is “12 Angry Men”, while “Alien” comes in third. Interestingly, Ridley Scott, director of “Alien”, also appreciates “2001”. However, it seems Nolan might be the film’s most ardent fan. Notably, Nolan played a significant part in the re-release of the original 1968 version of “2001: A Space Odyssey” in theaters in 2018, which he was too young to see when it initially premiered, but caught during a re-release in 1977. This cinematic experience on a 70mm screen left an indelible impression on him and served as inspiration for his future work. He expressed this sentiment in an interview with Entertainment Weekly in 2018, stating that the film stayed with him as a reminder of what movies could achieve, and that he wished to share this impactful experience with newer generations.

In the very same interview, Nolan emphasized his opinion that “2001” stands out as remarkably authoritative within the realm of science fiction. It’s indisputable that it holds immense influence over American sci-fi, especially. This groundbreaking film forever transformed cinema, serving as a template. As Nolan further explained, Kubrick possessed an extraordinary knack for storytelling with an understated yet powerful style – every element served a purpose, there were no unnecessary shots, lines, or words. This brings us to another fascinating paradox that “2001: A Space Odyssey” embodies: it manages to be both minimalist and maximalist at once. The sweeping narrative spanning millennia, the grandiose music, and meticulous cinematography coexist with a thought-provoking montage of scenes that feature minimal dialogue, no subplots, and individual images capable of conveying countless meanings.

Read More

- Who Is Harley Wallace? The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Bring Her Back’s Dedication

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- KPop Demon Hunters: Real Ages Revealed?!

- 100 Most-Watched TV Series of 2024-25 Across Streaming, Broadcast and Cable: ‘Squid Game’ Leads This Season’s Rankers

- Elden Ring Nightreign Enhanced Boss Arrives in Surprise Update

- Ultimate AI Limit Beginner’s Guide [Best Stats, Gear, Weapons & More]

- Umamusume: Pretty Derby Support Card Tier List [Release]

- Mirren Star Legends Tier List [Global Release] (May 2025)

- Lottery apologizes after thousands mistakenly told they won millions

2025-07-07 04:24