Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new Bayesian model combines the strengths of both approaches to deliver accurate and reliable predictions for complex physical systems.

This paper introduces the Bayesian Interpolating Neural Network (B-INN), a scalable and robust framework for uncertainty quantification in surrogate modeling and active learning.

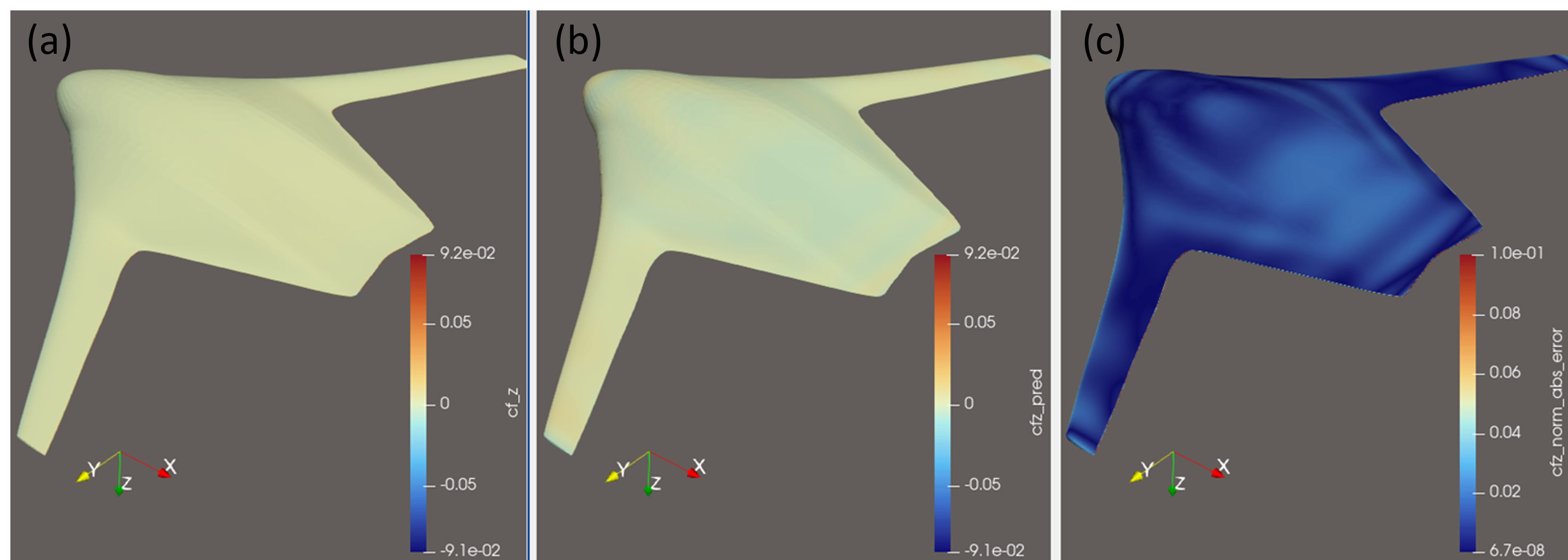

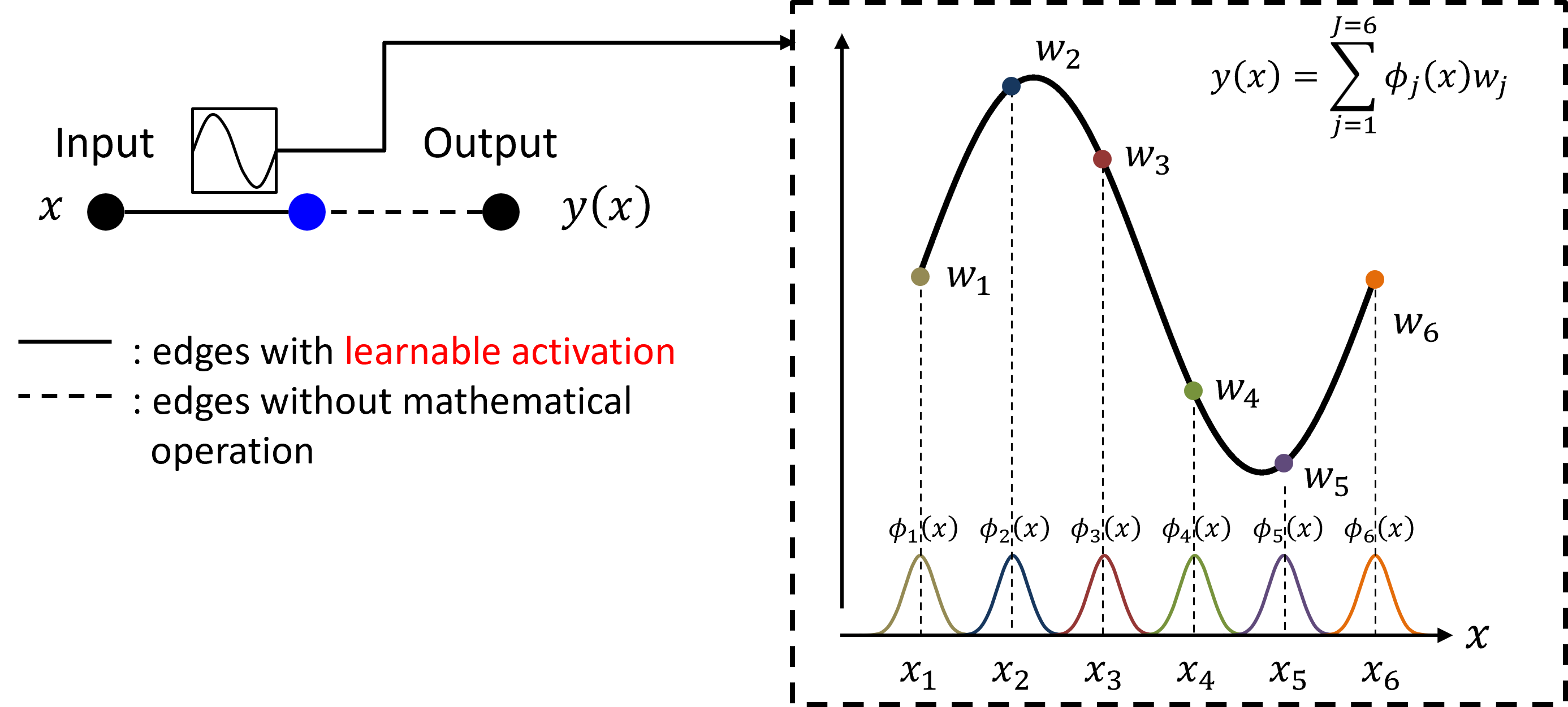

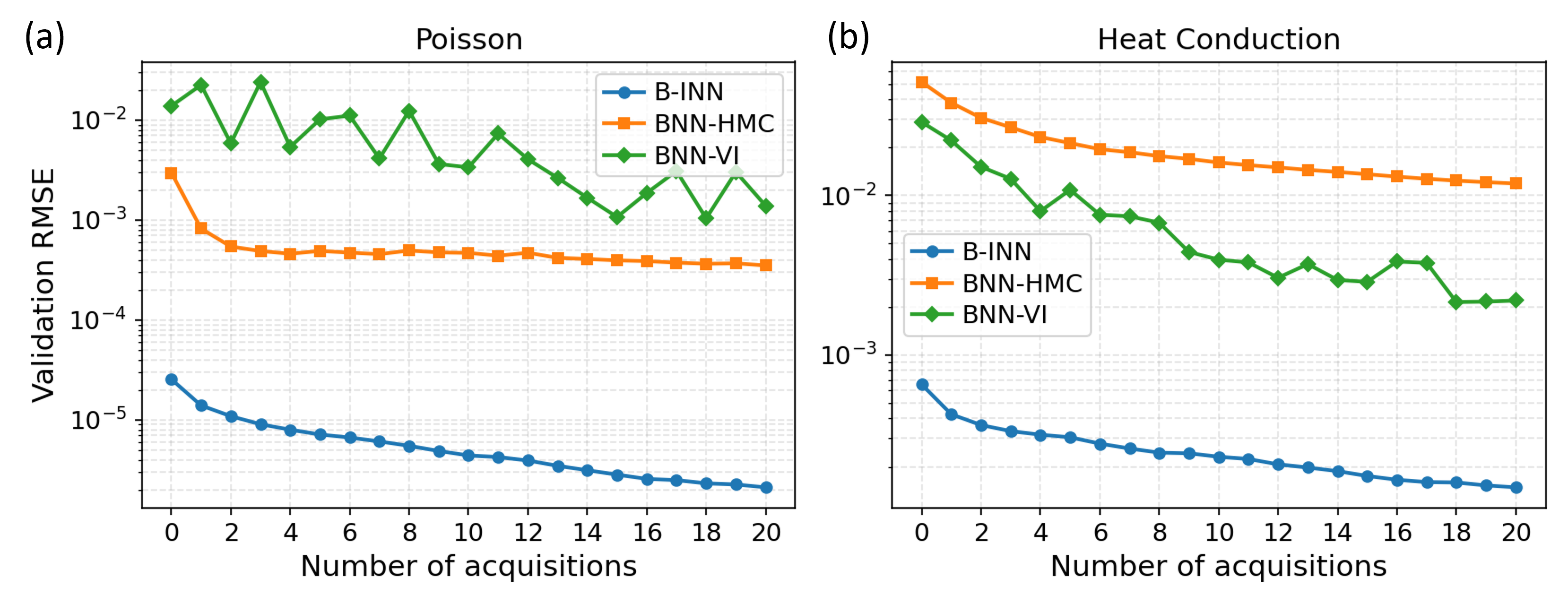

Despite advances in machine learning for uncertainty quantification, scalability and reliability remain significant challenges when applied to large-scale physical systems. This paper introduces the Bayesian Interpolating Neural Network (B-INN), a novel surrogate modeling approach designed to address these limitations. By integrating high-order interpolation with tensor decomposition and an alternating direction algorithm, the B-INN achieves linear complexity, \mathcal{O}(N), with respect to training samples while maintaining predictive accuracy comparable to Gaussian processes. Could this combination of efficiency and robustness unlock new possibilities for uncertainty-driven active learning in computationally intensive industrial simulations?

The Limits of Parametric Assumptions in Bayesian Inference

Conventional Bayesian modeling frequently necessitates the specification of a precise probability distribution – a parametric assumption – to represent the underlying processes within a system. This reliance, while simplifying calculations, introduces a potential for inaccuracy when applied to complex real-world phenomena that deviate from these pre-defined forms. For instance, assuming a normal distribution for data exhibiting heavy tails or multi-modal characteristics can lead to biased inferences and poor predictive performance. The strength of Bayesian inference lies in its ability to update beliefs with data, but this process is compromised if the initial, parametric assumptions are misspecified, ultimately limiting the model’s flexibility and hindering its capacity to accurately capture the nuances of intricate systems. Consequently, researchers are increasingly exploring non-parametric Bayesian methods that relax these rigid assumptions, allowing the data to inform the model structure itself, though at a considerable computational cost.

The inherent complexity of many real-world phenomena often necessitates the use of non-parametric Bayesian methods, which, unlike their parametric counterparts, do not impose rigid assumptions about the underlying data distribution. This flexibility allows these models to accurately capture intricate relationships and adapt to previously unseen data patterns, proving invaluable in fields like image recognition and financial modeling. However, this adaptability comes at a significant computational cost; non-parametric models typically require estimating an infinite number of parameters, leading to drastically increased memory usage and processing time. Consequently, tasks that are readily achievable with simpler, parametric models can become intractable for large datasets, demanding innovative algorithmic strategies and powerful computational resources to effectively harness the benefits of non-parametric Bayesian inference.

The practical application of Bayesian modeling faces a significant hurdle: computational scalability. While Bayesian methods offer a powerful framework for statistical inference, their effectiveness diminishes considerably when confronted with large datasets. Traditional algorithms, often reliant on matrix operations that scale poorly, frequently struggle with datasets exceeding just 10,000 data points, rendering them impractical for many modern applications. This limitation isn’t merely a matter of processing time; it impacts the feasibility of modeling increasingly complex systems in fields like genomics, finance, and climate science, where data volumes are continuously expanding. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring methods – including stochastic variational inference and distributed computing – to overcome these bottlenecks and unlock the full potential of Bayesian statistics for big data challenges.

Gaussian Processes: Elegance Constrained by Computational Cost

Gaussian Processes (GPs) represent a non-parametric Bayesian approach to regression and uncertainty estimation. Unlike parametric methods which assume a specific functional form and estimate a fixed number of parameters, GPs define a probability distribution over functions directly. This is achieved by defining a mean function and a kernel function – also known as a covariance function – which specify the relationships between data points. Predictions are made by conditioning on observed data, resulting in not only a point estimate but also a predictive distribution, allowing for the quantification of uncertainty in the form of a variance or standard deviation. The flexibility of GPs stems from the ability to choose different kernel functions, enabling the model to adapt to various data characteristics and complexities without being constrained by predefined functional forms. f \sim GP(m(x), k(x, x')) represents the core concept, where f is a realization from the Gaussian Process, m(x) is the mean function, and k(x, x') is the kernel function defining the covariance between points x and x’.

Gaussian Processes (GPs) facilitate efficient prediction and reliable uncertainty quantification when closed-form Bayesian inference is achievable. This means that, given a kernel function and observed data, the posterior distribution over functions can be expressed analytically, avoiding computationally expensive approximation methods like Markov Chain Monte Carlo. The posterior mean serves as the predictive mean, while the posterior covariance provides a direct measure of predictive uncertainty. This analytical tractability enables GPs to produce well-calibrated confidence intervals and probability estimates, crucial for decision-making in applications where quantifying prediction reliability is paramount. The predictive variance, derived from the posterior covariance, scales directly with the distance from observed data points, inherently capturing the concept of epistemic uncertainty – the uncertainty due to lack of data.

The computational complexity of Gaussian Processes (GPs) is a significant limitation, stemming primarily from the matrix inversion required during inference. Specifically, the time and space complexity scale as O(n^3) and O(n^2) respectively, where n represents the number of data points. This means that as the dataset size increases, the computational demands grow rapidly, making GPs impractical for large-scale problems. While approximations exist to mitigate this, they often introduce trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency. Consequently, GPs are generally restricted to datasets containing fewer than 1,000 data points; beyond this threshold, the computational cost can become prohibitive, even with optimized implementations and hardware.

Escaping Random Walks: Advanced MCMC for High-Dimensional Inference

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) addresses limitations of traditional Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods by leveraging concepts from Hamiltonian dynamics. Standard MCMC relies on local moves, leading to high autocorrelation and slow convergence, particularly in high-dimensional spaces. HMC reformulates the sampling problem as a physical system, introducing auxiliary momentum variables and using Hamiltonian dynamics to propose moves. This allows the sampler to explore the target distribution more efficiently by taking larger steps and traversing regions of low probability without being immediately rejected. The algorithm uses the gradient of the log probability density to guide the exploration, resulting in substantially reduced autocorrelation and improved mixing, thus offering a significant performance gain over methods like Metropolis-Hastings or Gibbs sampling when applied to complex, multi-dimensional distributions.

The No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) improves upon Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) by dynamically adjusting the step size during the trajectory, eliminating the need for manual tuning of this critical parameter. Standard HMC requires a user-defined step size; a value too small leads to slow exploration, while a large value risks overshooting the target distribution. NUTS automatically determines an optimal step size by monitoring trajectory behavior; specifically, it assesses when a U-turn occurs, indicating potential overshooting. By adapting the step size during each leapfrog iteration, NUTS increases sampling efficiency and achieves greater robustness across a wider range of posterior distributions without requiring extensive user intervention or pre-tuning.

Advanced Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, such as Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) and No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS), facilitate efficient exploration of the posterior probability distribution in Bayesian inference, particularly in high-dimensional parameter spaces. This efficiency stems from their ability to reduce random walk behavior and propose moves that are more likely to be accepted, enabling effective sampling from complex distributions. While these methods represent a significant improvement over traditional MCMC, computational demands still increase substantially with dimensionality and dataset size. Consequently, scaling to datasets containing millions or billions of data points remains a challenge, often requiring approximations, parallelization, or specialized hardware to achieve reasonable computation times. Current research focuses on addressing these limitations to extend the applicability of these methods to truly massive datasets.

Strategic Data Acquisition: The Power of Active Learning

Active Learning represents a paradigm shift in data acquisition, moving beyond random sampling towards intelligent selection of instances for labeling. Rather than passively accepting all available data, this approach proactively identifies the data points that will yield the greatest improvement in model performance. By focusing on instances where the model is most uncertain or where disagreement among models is highest, Active Learning strategically reduces the labeling effort required to achieve a desired level of accuracy. This prioritization is particularly valuable when labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain, offering a cost-effective route to building high-performing machine learning models and maximizing the information gained from each labeled example.

Active Learning presents a powerful alternative to traditional data acquisition methods by strategically selecting which data points require labeling. Rather than passively accepting a large, often redundant, dataset, this approach iteratively queries an oracle – a human annotator or reliable source – for labels on only the most informative instances. This targeted labeling process allows machine learning models to achieve performance levels comparable to those trained on much larger, randomly selected datasets, but with a fraction of the labeling effort. The efficiency stems from focusing on data points where the model is most uncertain, thereby maximizing the information gained from each new label and accelerating the learning process. Consequently, Active Learning proves particularly valuable in scenarios where obtaining labeled data is expensive or time-consuming, offering a practical pathway to building accurate models with limited resources.

The synergy between Active Learning and Gaussian Processes unlocks a powerful approach to Bayesian inference, particularly when dealing with extensive datasets. This combination doesn’t simply scale existing methods; it fundamentally optimizes the process of model training by strategically selecting data points that maximize information gain. Research indicates consistent performance improvements over traditional baselines throughout an active learning cycle – specifically, across 20 iterative rounds of data acquisition and model refinement. This efficiency stems from the Gaussian Process’s ability to quantify uncertainty, allowing the Active Learning algorithm to intelligently query labels for instances where the model is most unsure, thereby minimizing labeling costs while simultaneously boosting predictive accuracy. The result is a computationally efficient system capable of achieving high performance with significantly fewer labeled examples than conventional methods require.

The pursuit of robust surrogate modeling, as demonstrated by the Bayesian Interpolating Neural Network, echoes a fundamental tenet of mathematical rigor. The B-INN’s capacity for scalable uncertainty quantification, combining Gaussian Processes with neural networks, aligns with the notion that a solution’s validity isn’t merely empirical but inherently provable. As Pyotr Kapitsa observed, “It is better to be a little bit wrong than perfectly vague.” This resonates with the B-INN’s approach; by explicitly quantifying uncertainty, it avoids the ‘vagueness’ of point estimates, offering a more reliable and mathematically grounded approximation for complex physical systems, even if not perfectly precise. The network’s architecture prioritizes a demonstrable understanding of prediction ranges over simply achieving a low error on training data.

What Remains to be Proven?

The presented Bayesian Interpolating Neural Network, while demonstrating a pragmatic synthesis of Gaussian Processes and Neural Networks, merely shifts the locus of difficulty rather than eliminating it. The claim of scalable uncertainty quantification rests, fundamentally, on the validity of the interpolating kernel – a function whose properties demand far more rigorous examination. Current evaluations, while encouraging, are insufficient to establish the kernel’s behaviour in truly high-dimensional spaces, or with datasets exhibiting significant non-stationarity. A proof of convergence, demonstrating that the posterior distribution genuinely reflects the underlying physical reality, remains conspicuously absent.

The application to active learning, while intuitively appealing, is predicated on the assumption that the B-INN’s uncertainty estimates are calibrated. In other words, a predicted confidence of 90% should, in reality, encompass the true value 90% of the time. Establishing this calibration, particularly in scenarios where data is sparse and extrapolation is necessary, will require not just empirical validation, but a formal, mathematically-grounded analysis of the posterior’s statistical properties. Simplicity, it must be remembered, does not equate to brevity; it resides in the absence of internal contradiction.

Future work should therefore prioritize theoretical investigations into the kernel’s properties and the calibration of uncertainty estimates. Only through such rigorous analysis can this approach transcend the realm of ‘works on tests’ and approach a genuinely elegant, provable solution for surrogate modeling. The pursuit of practical performance, without a corresponding commitment to mathematical purity, is, ultimately, a fool’s errand.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.22860.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- BREAKING: Paramount Counters Netflix With $108B Hostile Takeover Bid for Warner Bros. Discovery

- Elder Scrolls 6 Has to Overcome an RPG Problem That Bethesda Has Made With Recent Games

- Heated Rivalry Adapts the Book’s Sex Scenes Beat by Beat

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- Gold Rate Forecast

2026-02-03 06:30