Wes Anderson stands out as a prominent cinematic stylist currently active in the film industry. His visual style is instantly recognizable and serves as the defining characteristic of his work, a consensus that even his critics acknowledge. Although the aesthetic of his films has subtly changed throughout the years, there’s no mistaking a piece by Anderson.

The question at hand revolves around the extent to which his work matters. However, this isn’t about personal preferences – some people appreciate his artistic decisions, while others do not. Yet, each of his films spark a recurring debate on style versus content, with some questioning whether he excels only in style and not substance. Critics who disregard him often focus solely on his style, labeling his new work as an overemphasis of Wes Anderson’s style, and consider it without further analysis.

You could rephrase that statement as follows: “One might assume I’m all about style over substance, but I believe that Wes Anderson’s unique aesthetic is the essence of what he does. If someone believes they must peel back his cinematic layers to find the emotional depth, they are searching in the wrong place. The evidence of this can be seen throughout his filmography, from the tightly wound narratives of his early works, to his mid-career exploration of metatextuality in ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’, and even to his latest release, ‘The Phoenician Scheme’, which I believe pushes the boundaries in an intriguing way.

Wes Anderson’s Conspiratorial Style, Explained

Rethink The Traditional Relationship Between Style & Story

It’s typical for viewers to perceive a movie’s visual approach as something that has been imposed upon it, particularly in meticulously crafted films like those of Anderson. Directors are often depicted as strong-willed and precise individuals who use their movies to mold the world according to their vision, leading audiences to interpret aesthetic decisions as direct manifestations of their will. Elements such as character development and plotline are usually presented before the camera, while style is added afterwards; overdo it, and you risk overwhelming them.

I believe there’s an issue here that isn’t typically correct. This problem lies in an outdated perspective about the existence of a single, objective truth that can be captured through photography or film, without any personal bias. However, in this instance, it is incorrect in a unique manner. In Anderson’s body of work, the connection between style and narrative is almost harmonious. It’s not something he imposes on his characters, but rather something he cultivates for them. I like to refer to it as a collaborative style.

Wes Anderson’s typical main characters often find themselves at odds with the perception of reality in their lives. Somehow, society doesn’t fully appreciate or understand them as they perceive themselves. However, instead of contradicting them, Anderson portrays these characters according to their self-image – presenting them to us as they wish to be seen.

This can be traced back to “Bottle Rocket,” his first directorial feature film, and it includes the unexpected romance between Anthony and Inez, but more notably, the unsuccessful heist masterminded by Owen Wilson’s quirky character, Dignan. If the sequence that comes to mind most when looking ahead to his signature style is because Anderson started becoming more intrigued by characters like Dignan rather than Anthonys. However, I believe it’s a key characteristic of all his work.

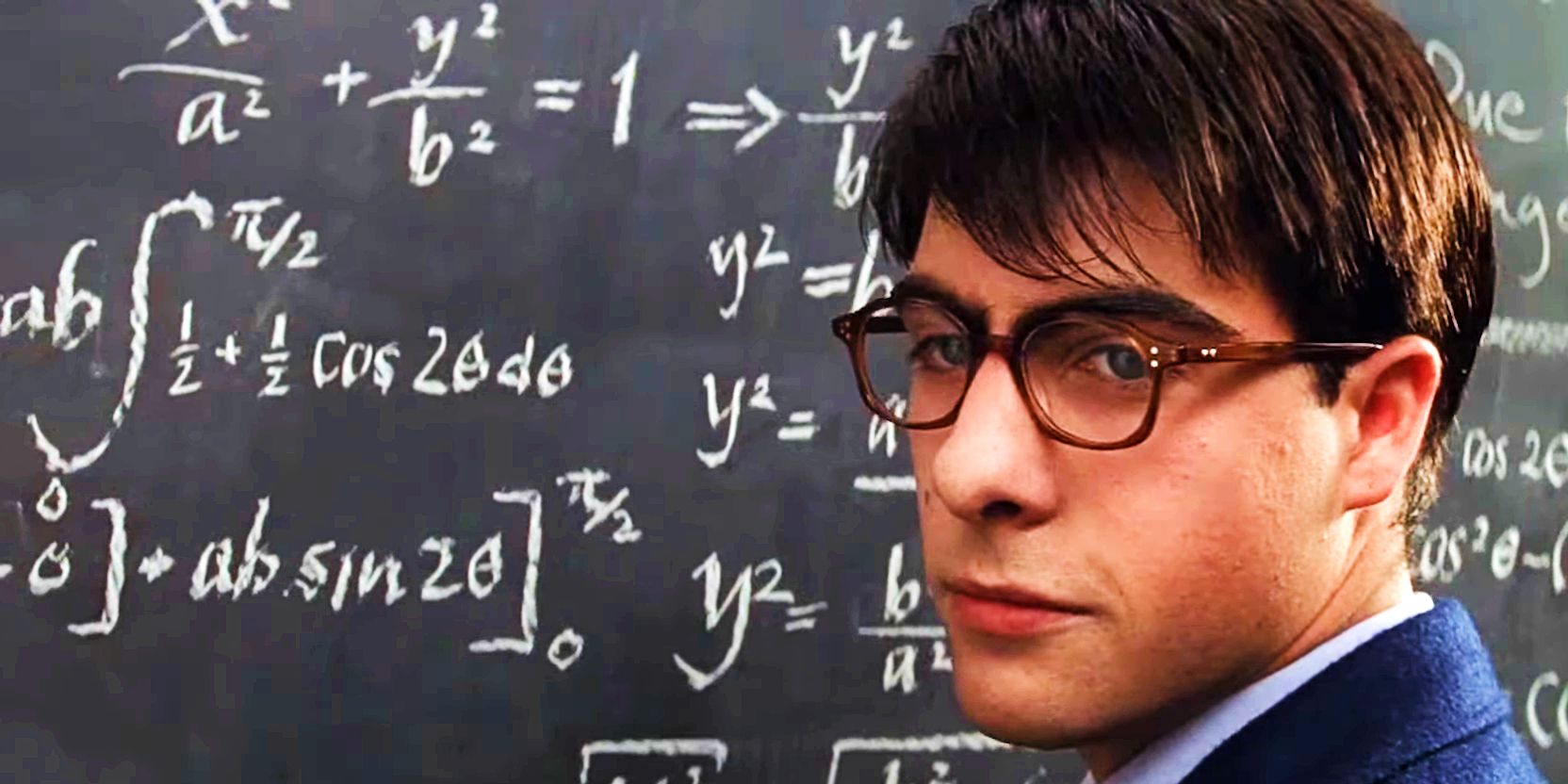

In each movie, Wes Anderson portrays his main characters as they see themselves – images that are quite different from the way others perceive them. Max Fischer of Rushmore is a misfit who thinks of himself as the school’s most esteemed citizen, while The Fantastic Mr. Fox’s title character is a self-proclaimed master thief dealing with midlife issues. In Moonrise Kingdom, Sam and Suzy are two lonely, misunderstood children who find in each other the wild escapades and fairy tale romance they were both yearning for.

Wes Anderson’s Movies Are Full Of Emotion

And His Style Helps Us Understand It

Specifically that element serves as a vessel for the substance in question. In none of his films is the obscurity so dense it can’t be penetrated, leading instead to narratives that revolve around the emotions Anderson helps the characters conceal. Emotions such as disillusionment, sorrow, solitude, purposelessness, frustration, self-contempt. If you approach these films with this insight from the outset, they seem overflowing with raw emotion.

More frequently than not, there are instances when the cup becomes too full. It’s less about the truth emerging from beneath the veil of artistic expression, but rather the character hidden under that veil deciding to reveal it. These moments could be as subtle as a poignant line of dialogue or an actor’s revealing close-up, and Anderson doesn’t linger on them, allowing the narrative to progress at its steady pace. However, if you notice these instances for what they truly are, they can pack quite a punch.

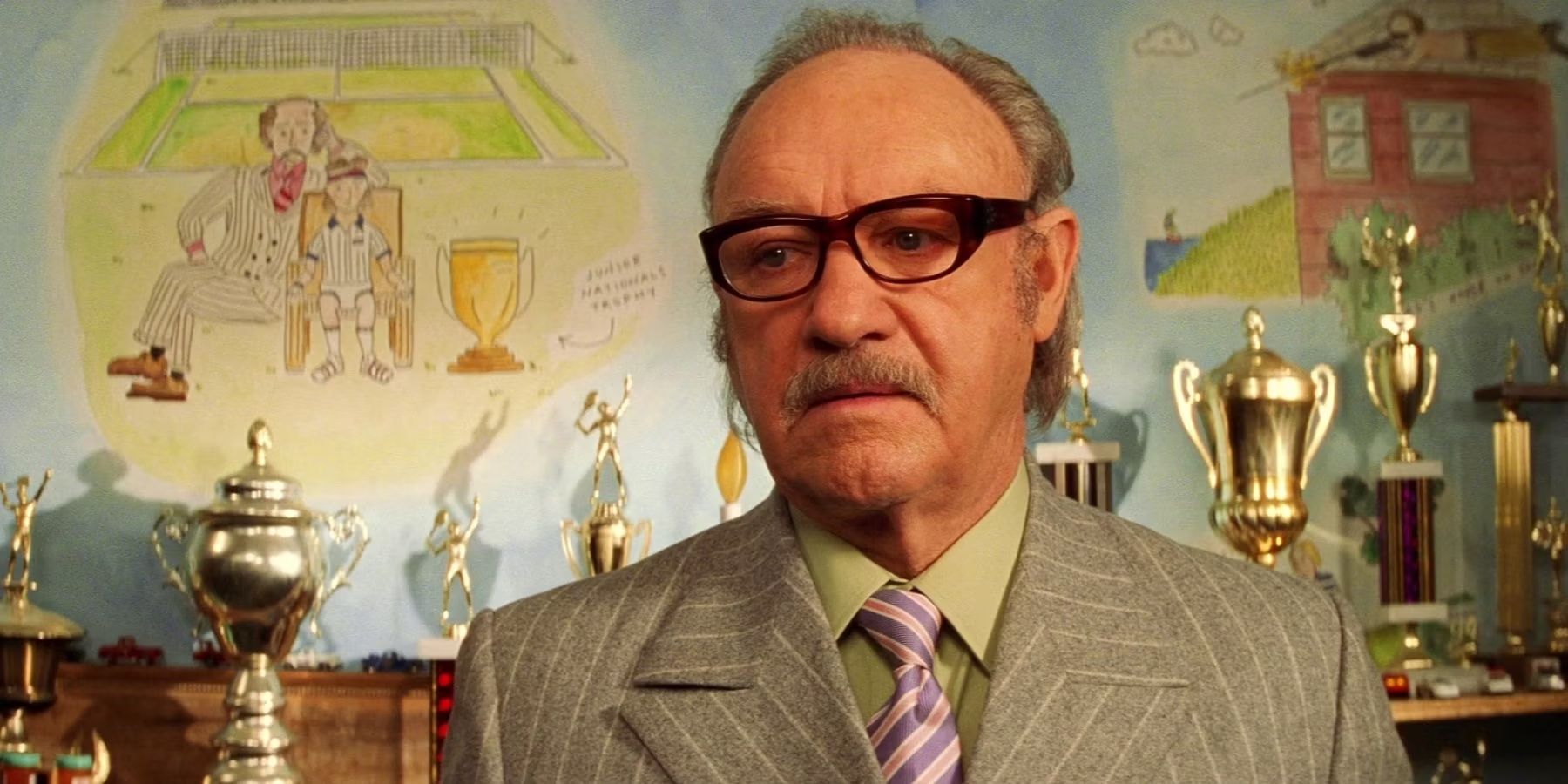

In the eyes of many viewers, Wes Anderson’s film “The Royal Tenenbaums” stands out as his most emotionally relatable work. This is due to the fact that the movie’s unique style starkly contrasts with everyday life from the very beginning. The Tenenbaum family clings fiercely to an image from their past, a past where their emotional struggles were skillfully hidden beneath their ‘child prodigy’ personas. Now, however, these struggles are not so well concealed. They are palpable, simmering just below the surface. Thus, when Chas says, “I’ve had a tough year, Dad,” it feels as though all their collective pain is encapsulated in that single, poignant moment.

In Moonrise Kingdom, a film I particularly admire, the characters of Suzy and Sam, and their poignant love story, hold significant importance. However, the adults in this narrative are often portrayed from the perspective of these young protagonists, falling somewhat outside Anderson’s distinctive aesthetic. With the exception of Sam’s Scout Master, who holds a certain respect, they are predominantly depicted as frustrated, disheveled, and melancholic – a recurring theme in every Wes Anderson production, though it may not always appear so.

With The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson Went Meta

And His Stories Have Become About His Storytelling

In one of Wes Anderson’s most celebrated films to date, The Grand Budapest Hotel, we see a significant shift in his narrative style. Prior works had relied on voiceover narrators or storybook-like framing devices. However, this movie employs a matryoshka doll structure: a woman reading a book by an author who recounts a conversation with the hotel owner, who in turn shares tales of the past and the hotel’s golden era. Starting a film by traversing multiple layers of narration draws immediate attention to these elements.

Through self-examination, Anderson scrutinizes his own storytelling abilities. It’s evident that the method a story is conveyed reveals its creator; just as Zero’s viewpoint permeates the narrative of Gustav H., so too does Anderson’s perspective suffuse his films. However, it goes deeper than that – style mirrors the bond between the narrator and the tale. The movie’s setting, predominantly in the past, is made captivating like one of Mendl’s pastries because, for Zero, this narrative is an expression of affection. The film delves into the emotional essence of style.

I’ve delved deeper into the concept presented in this film, not just understanding its application within my own creative process, but also exploring how it mirrors a renowned magazine like The New Yorker. In reality, Wes Anderson has cleverly adapted an offshoot of a Kansas newspaper set in a quaint French village to emulate the essence of The New Yorker. Just as institutions often strive to project a desired image, this film subtly portrays The French Dispatch as more than just a small-town publication.

One reason why I adore The French Dispatch among Wes Anderson’s works is its unique approach to depicting what exceptional writers can bring to their subjects. Each segment in this collection has its own distinct flavor, mirroring not only the character behind the story but also their perspective on the topic they’re presenting. He allows us a glimpse into their shaping of the truth, and it’s thrilling – it is through these writers that we witness an unstable inmate transform into an eccentric genius, a stubborn boy blossom into an inspiring revolutionary, and a police chef evolve into a profound artist.

Just like how Asteroid City shares some similarities, it’s not straightforward to decipher the events (and that’s not the main focus anyway). However, Anderson masterfully creates an illusion by portraying a play as if it were a real movie, as if the collective imagination of the actors makes it come alive. The film also mirrors how The French Dispatch reflects on writing; performances in this movie are characterized by their unique style and the actors embody their characters with great reverence, much like a director would.

In The Phoenician Scheme, Wes Anderson Tries Something A Little Different

And It Hints At His Next Career Chapter

Without much surprise, the debut of “The Phoenician Scheme” at Cannes sparked responses labeling it as another typical Wes Anderson film. However, if you’re similar to me, this movie will seem quite distinct. It carries a witty darkness, but lacks the characteristic lively tone that typically graces his works. Despite the weighty emotions in his narratives, they often appear less intense after he collaborates with his characters to reframe them, making them feel lighter than they are.

This newest feature is arguably Anderson’s most challenging, and I found myself pondering why for a while. However, I’ve come to understand that it’s due to the fact that this time, he isn’t collaborating with his characters. Instead, he seems to be working against them.

Sort of.

In a different phrasing,

Benicio del Toro’s character Zsa-Zsa Korda, portrayed by Anderson, isn’t your typical hero on the surface. He appears as an affluent, ruthless tycoon in the world of industry, showing little remorse when employing slave labor for his significant construction project. Throughout the film, he seems puzzled when people don’t blindly obey his commands. The eulogy heard at the start, mistakenly played under the assumption that he perished in a plane crash, is far from flattering.

However, the individual portrayed in stories isn’t truly the person we perceive on screen. In a shift from Alexander Korda’s previous cinematic presentations, this persona appears to be a mask he adorns – and the style of “The Phoenician Scheme” is peeling it off. The camera angles that bolster his self-portrayal are overly dramatic, bordering on mockery, and his visage is consistently scarred by untidy wounds. Scene after scene, his supposed toughness and business acumen are undermined, as each (frequently pitiful) effort to dupe his business partners into funding The Gap falls flat.

Not only Korda, but Liesl and Bjørn also employ disguised emotions, and The Phoenician Scheme gradually peels back their layers until their genuine feelings are exposed. Unlike The French Dispatch or Grand Budapest, the scheme itself is not glamorized; instead, it appears childish and insignificant. Over the course of the story, viewers may begin to question the significance of what they’re watching: What makes us invest so much emotion in this narrative?

In essence, Anderson crafts plots where his characters are deceived, yet it’s for their ultimate benefit. Through the examination of the falsehoods people use in self-portrayal and the extent they cling to these facades that they lose sight of their identities, he leads Korda, Liesl, and Bjorn towards authentic living. By the conclusion, where the father and daughter are struggling financially while operating a restaurant, “The Phoenician Scheme” ultimately resonates as a typical Wes Anderson production.

Following the distinctive four short films based on Roald Dahl, this movie seems to signify a fresh phase in Wes Anderson’s cinematic journey. The intriguing bond between him and his main characters could evolve into unexplored relationships. Regardless of what’s next, I am confident it will continue to exude his signature style with depth.

Read More

- Who Is Harley Wallace? The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Bring Her Back’s Dedication

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- Elden Ring Nightreign Enhanced Boss Arrives in Surprise Update

- KPop Demon Hunters: Real Ages Revealed?!

- 100 Most-Watched TV Series of 2024-25 Across Streaming, Broadcast and Cable: ‘Squid Game’ Leads This Season’s Rankers

- How to play Delta Force Black Hawk Down campaign solo. Single player Explained

- Here’s Why Your Nintendo Switch 2 Display Looks So Blurry

- MrBeast removes controversial AI thumbnail tool after wave of backlash

- Basketball Zero Boombox & Music ID Codes – Roblox

2025-05-31 16:10