As a dedicated cinephile, I must caution you about upcoming spoilers for the blockbuster film titled “Universal Language,” which hit the big screen on Valentine’s Day and became available for digital rentals starting April 8th.

In the film titled “Universal Language“, Winnipeg is portrayed as a parallel universe equivalent of Tehran. When director Matthew Rankin and his collaborators, Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati, showed their movie in these cities, both Iranians and Canadians believed it was specifically created for them. This is exactly what “Universal Language” aims to achieve, asserts Rankin, by “examining something commonplace from an unusual perspective and rediscovering it afresh.

In their own words, Winnipeggers expressed that they had never encountered a more genuine portrayal of their city than the one presented in the movie, which is surprisingly in Farsi. Similarly, residents of Tehran felt a strong connection, stating that the film was theirs and seemed tailor-made for them. This was particularly gratifying for Rankin, as these individuals were unaware of Tim Horton, yet they still resonated with the movie. The screenings in both locations left him feeling a sense of echo or shared experience.

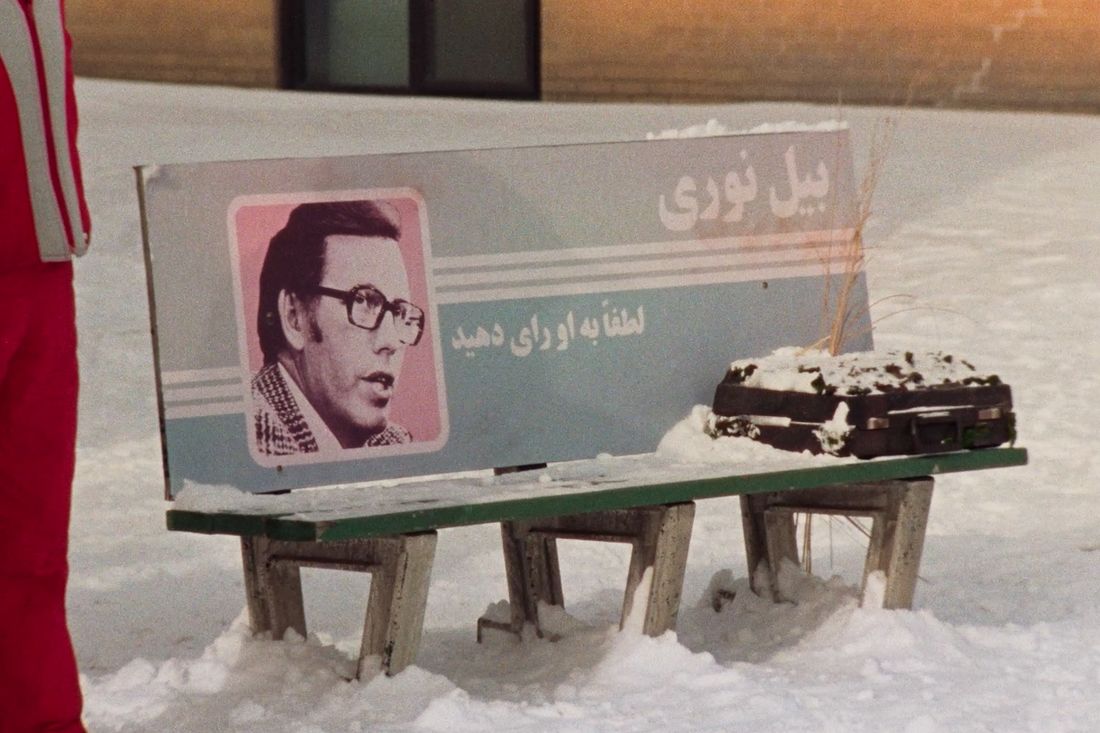

A significant aspect of the movie, titled “Universal Language,” blends humor and sadness, drawing from Winnipeg’s local culture and Iranian film traditions. Public spaces showcase posters of Canadian politicians, street vendors sell Iranian cuisine, and youngsters attempt to master French while speaking Farsi. Since its screening in Tehran last December, the movie has spread widely, almost virally, in Iran as a result of leaked screeners. As Rankin explains, “We aimed to establish a platform where Iranians could watch it for free. However, they outsmarted us, so now they’re just enjoying it.” The film’s set design, art direction, and cinematography collectively construct a vibrant, often surreal, and consistently multicultural visual backdrop.

According to Rankin, the objective was to create an environment where it’s hard to identify the city. You might be in one city, another, or even both simultaneously. Here, Rankin discusses five of the film’s most potent visual symbols and explains how they are shaped by the two dominant cultures found within Universal Language.

The Kleenex

In Winnipeg, the most vibrant interior can be found in the Kleenex Emporium, adorned with countless boxes of Kleenex featuring a unique gold-and-blue dot pattern. This Iranian community, as portrayed in the film, finds solace in using tissues during emotional moments: A specialist focusing on tears (a lacrimologist) distributes Kleenex at funeral services, and a year’s worth of Kleenex is given as a prize for the town’s Bingo night.

In Ila’s perspective, finding Kleenex in Iranian households has always been amusing, as demonstrated during a dinner party when Negin Abbasi, our friend, carried a box of Kleenex, jokingly asking guests if they wanted to cry or needed tissues. This character inspired by Negin and my late friend Louis Negin was incorporated into the film, but unfortunately, Louis didn’t make it. The improvised plot revolved around this character having a unique job – comforting people in a cemetery by distributing Kleenex. There’s an underlying sadness yet humor in this concept, which aligns with the movie’s preferred tone. Remarkably, the cemetery setting was inspired by my personal experience visiting my great-grandparents’ gravesite outside Winnipeg, where a peaceful field once stood before a massive highway was constructed adjacent to it in the 1960s.

The funeral scene was captured in a series of miniature green areas nestled amidst the underbelly of a bustling freeway in Montreal. These pockets of greenery, often overlooked due to their proximity to busy highways, were used as filming locations. Humans rarely venture into these places. The movie explores poetry within such seemingly insignificant spots, which is a key aspect of its absurdism. It’s about the juxtaposition of the sacred and mundane, the divine and profane, the sublime and the ludicrous. Interestingly, filming in these locations proved less challenging compared to finding clearances for shooting against beige walls. Permission was granted swiftly, perhaps because such requests were unprecedented. The city, it seems, readily agreed as no one had ever asked to shoot there before.

In an effort to create a Kleenex room reminiscent of a shoe store overflowing with Kleenex, the design concept was influenced by the vintage Windsor salt logo. Louisa Schabas’ son meticulously added the dots on the box, a task that took him several days, though he wasn’t entirely alone in this endeavor. The majority of the work was done by him. In the store, Negar Nemati, our costume designer, drew inspiration from old images of Anoushiravan Rohani. He penned “Tavalodet Mobarak,” the Iranian birthday song, and often dressed in a white tuxedo adorned with frills and a tie. We felt that this tuxedo had a certain similarity to Kleenex. Our friend Aonan Yang was styled to resemble Anoushiravan Rohani. Essentially, every element serves to emphasize and enhance the concept of a unique Kleenex store.

The flower shop

The movie centers around two siblings, Nazgol and Negin, on their quest to locate a pair of lost glasses owned by Negin’s friend Omid. Nazgol frequently visits the town’s flower shop, where the florist advises patrons to whisper due to the flowers’ delicate nature. As per Schabas, the florist primarily creates unique blooms by rearranging pre-existing artificial flowers. Eventually, a potted crocus (Manitoba’s national flower) that Nazgol buys ends up in Matthew’s possession as he visits his father’s grave.

One aspect of the films we’re discussing that I find captivating is how they portray actions. Instead of always focusing on an active protagonist and following the action, as is common in Western cinema, these films often emphasize the listener rather than the speaker. The camera may even move away from the action to focus on something near it. This means you don’t always see the most dramatic events unfold – they are left to your imagination. This approach encourages viewers to develop their own connection with what they’re watching.

Instead of revealing Hamid Shafii (the flower man), we opted to maintain an atmosphere suitable for children throughout the film. This decision was a collective thought between me and cinematographer Isabelle Stachtchenko. By omitting the character’s face, we intended to create intrigue about the hidden figure, concealing their facial expressions from the audience. This uncommon choice in western cinema sparks questions that are usually not considered while watching a film.

In addition, we aimed to vividly depict the room. Louisa Schabas adorned that space with an abundance of chrysanthemums. As a matter of fact, we drew inspiration from Close-Up for this scene. Towards the end of that film, Hossain Sabzian presents the Ahankhah family with a towering bouquet of flowers, and it’s a truly memorable scene. He plucks one flower, only to replace it with another, then hops back on his bike. The act is far from graceful. The type of flower featured in the movie is indeed chrysanthemum.

The Christmas-tree man

The color scheme used in Universal Language’s exterior is intentionally muted, filled with shades of gray, beige, and brown that mirror the city of Winnipeg’s brutalist architecture in the movie. (Many areas within Winnipeg are named after these colors.) However, one character stands out as a striking, radiant sight: the Christmas-tree man, whose form is an enchanting blend of ornaments, tinsel, and lights. Nazgol and Negin treat him with the same politeness as they do every other adult in the film.

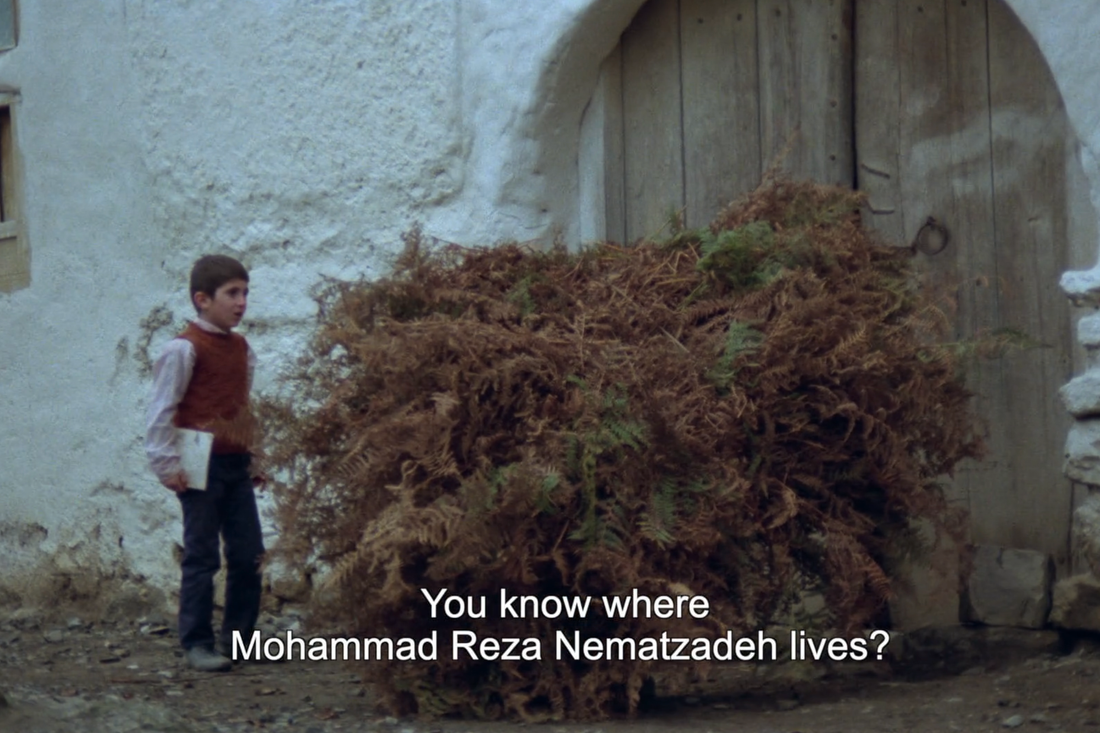

In the captivating scene from the film “Where Is the Friend’s House?“, a child is on a quest to find his friend’s house. As he runs from Koker to Poshteh, he encounters a man laden with wood, resembling a character straight out of a Jim Henson production. This scene pays homage not only to the film’s director Abbas Kiarostami but also to John Paskievich, a Winnipeg street photographer whose work in the 1970s and 1980s captured the heart and peculiarities of his city. One of Paskievich’s images features a man walking down the street with an enormous pile of rugs on his back, mirroring the character in the film. However, this man wears striking striped pants that our costume designer, Negar Nemati, managed to find near-identical replicas for the Christmas tree character. Both Paskievich and Abbas Kiarostami’s son, Ahmad, were thrilled by this nod to their work when they saw it.

Growing up on my street, there was an extraordinary woman who embodied the Christmas spirit year-round. She’d adorn herself in tinsel, don a star or angel headpiece, and sport a cedar boa around her neck. This lady, utterly enamored with Yuletide, wouldn’t hesitate to wish “Merry Christmas” even during August. As children, we cherished her unique fashion sense, and our interactions with her were always an exciting spectacle. Although she disappeared from our neighborhood when I was young, I can only assume that the adults may have viewed her in a more ironic light. But for us kids, she was simply a vibrant character whose style we admired without a second thought. Just as children would ask directions from a person dressed as a tree, we found nothing odd about encountering this festive figure on our street. [Laughs] That’s my humble tribute to that remarkable woman and the city of Winnipeg.

The suitcase

In my perspective as a movie reviewer, the story unfolds with the protagonist, Matthew, meandering through Winnipeg’s streets. He comes across a tour group, guided by Massoud (Pirouz Nemati). They pause at an abandoned suitcase on a bus bench, a relic from years past that has remained untouched. According to Massoud, this forgotten item is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site because it symbolizes “an enduring monument to the most profound human solidarity, even in its simplest and mundane forms.”

This scene resonates with an earlier moment in the film where Matthew himself abandons his suitcase on the external staircase of his office building in Montreal.

In Iran, during my journey, I experienced an unusual incident. I boarded a train from Tehran heading towards Kashan, only to realize upon arrival at the station that I had left a bag on the platform. Inside were personal items like a journal and a book, things I deeply cared for. After returning to Tehran on another train, approximately eight hours had passed. Miraculously, when I returned to the platform, my bag was still in the same spot, untouched on the bench. This act of kindness resonated with me profoundly – nobody had disturbed it. This heartwarming story has stayed with me and eventually became a part of the film’s narrative.

During the tour, someone asked about the contents of the briefcase, to which Pirouz replied that no one has ever looked inside. In my memory, there was something in it, but for some reason, neither Pirouz nor I were privy to its contents. It appears Louisa Schabas may have placed something in it. I seem to recall asking her about the contents, and she responded cryptically by saying, “I’ll never tell you.” By the way, I’m quite fond of benches – so much so that I made a film about their placement, titled Municipal Relaxation Module.

The turkeys

As a movie enthusiast, allow me to share my thoughts on “Universal Language.” This film cleverly references Kanoon, the esteemed Iranian Institute for Children’s Literature, with a nod in its design. The institute’s goose logo is reimagined as a turkey, skillfully crafted by Iranian graphic designer Mohammad Jalali. Two of the characters, older butcher brothers, are specialists in raising turkeys and form an unlikely bond with a special turkey over the internet. This feathered friend embarks on a journey from its digital world to Winnipeg, causing a bit of inconvenience for a disgruntled fellow bus passenger, and eventually stealing a young boy’s glasses. The climax of the film sees this turkey evading its intended fate and joining a flock of wild turkeys roaming freely around Winnipeg, living life on their own terms.

In the film Close-Up, there’s an intriguing scene at the start where a group is searching for the Ahankhah house. They ask a man with several turkers under his arm for directions, and he offers them one of his turkeys. However, they decline and move on. This image of the man carrying a large number of turkeys was something that caught our attention, leaving us curious. We pondered whether this was simply a coincidence – perhaps this man just happened to be passing with turkeys at that moment – or if the director intentionally placed him there and decided he should carry turkeys. Alternatively, did he encounter someone who naturally carried turkeys and then stage this encounter? This small detail in the movie left us puzzled yet captivated. The film also has a few other subtle references to turkeys.

A while back, I had the good fortune of attending the MacDowell Residency where I crossed paths with one of my most admired American poets, CAConrad. Originally hailing from Philadelphia, this artist shared an interesting tidbit about our nation’s symbol – the bald eagle. It turns out that Benjamin Franklin, in his wisdom, proposed the wild turkey as a potential national bird, considering the bald eagle as a bird of questionable character due to its tendency to plunder nests of other birds. In Franklin’s view, turkeys represented unity and community – they travel in flocks, after all.

The film we watched featured a solitary turkey embarking on an uncertain journey, which in many ways mirrored the movie’s hopeful message. As the story unfolded, this turkey found itself intertwined with a group of peculiar children and their captivating tale. By the end of the film, our feathered friend had discovered its own community amidst the streets of Winnipeg, strutting off together on an impromptu adventure they shared.

What ultimately convinced us was the term “turkey.” In numerous languages, it symbolizes a bird native to different regions. However, in English, it signifies the nation of Turkey. Interestingly, in Turkish, it’s called “hindi,” which actually means India. Similarly, in French, we say “dinde,” which translates to “from India.” In Portuguese, the bird originated from the Netherlands. It’s a bird that defies geographical boundaries and is indigenous to North America. This aspect was intriguing to us as well. Moreover, Persian is one of the rare languages that has its own term for “turkey,” which is “buqalamun.” The film’s title in Farsi is “Avaz e’Buqalamun,” which means “Song of the Turkey.

During filming, our acquaintance Faraz Anoushahpour served as our on-set cinematographer and frequently collaborated with the turkey wrangler Michel Fournier. The solitary turkey you see in the movie is always the same one. When we filmed scenes on the bus featuring our friend Hemela Pourafzal, who shares screen space with the turkey, it was springtime. Michel mentioned that due to the season, there was a possibility the turkey might attempt to court Hemela, although this isn’t evident in the final cut. To prevent any unwanted advances, there’s plexiglass separating them. Despite the humor, I must admit that the turkey provided a deeply moving and complex performance, which we thoroughly enjoyed working on. We asked Michel about the turkey’s moniker, and he revealed it didn’t have one – it was a wild turkey. In our creative liberty, we decided to name him Hormuz.

Read More

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- Quarantine Zone: The Last Check Beginner’s Guide

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- Ultimate Myth Idle RPG Tier List & Reroll Guide

- Lucky Offense Tier List & Reroll Guide

- Mirren Star Legends Tier List [Global Release] (May 2025)

- Every House Available In Tainted Grail: The Fall Of Avalon

- How to use a Modifier in Wuthering Waves

- Basketball Zero Boombox & Music ID Codes – Roblox

- Enshrouded Hemotoxin Crisis: How to Disable the Curse and Save Your Sanity!

2025-04-16 15:55