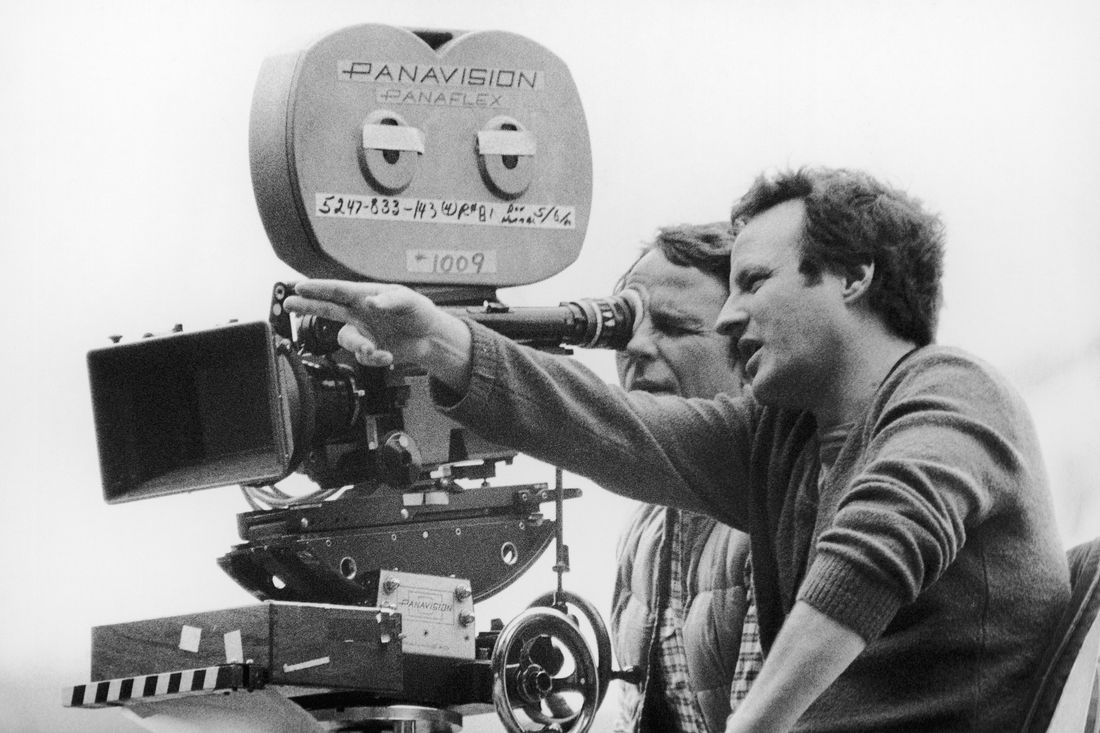

1981 saw Michael Mann’s film “Thief” receive mixed reviews and moderate box-office performance, but it has since gained recognition as a classic. This is typical for Mann, whose movies often find their audience over extended periods, even decades. The impact of “Thief”, which was recently released in 4K by the Criterion Collection and can currently be streamed on the Criterion Channel, was noticeable soon after its premiere. With its electronic soundtrack, emphasis on visual style, and oscillation between romanticism and isolation, the film anticipated what many identified as the MTV aesthetic.

Beyond just recognizing Thief‘s accomplishment, it’s crucial to understand the political undertones in Michael Mann’s perspective. The film portrays Frank (James Caan), a skilled and autonomous thief, as being manipulated and profited from by the infamous Chicago Outfit. At first, Frank is reluctant to collaborate with these mobsters. However, he has aspirations for his life, including marrying Jessie (Tuesday Weld) and starting a family, which necessitates more financial resources. Consequently, he aligns himself with the Outfit to accomplish larger heists. In return, they attempt to manage his life and retain most of the profits, intending to reinvest it in shopping mall ventures. Mann has often emphasized that the central theme of labor exploitation in Thief can be applied to various workplaces. Frank articulates this concept when he tells Leo (Robert Prosky), a complex Outfit boss, “I can see my money is still in your pocket, which is from the yield of my labor.” This dialogue was cited during the 2023 WGA-SAG strike pickets, demonstrating its enduring relevance.

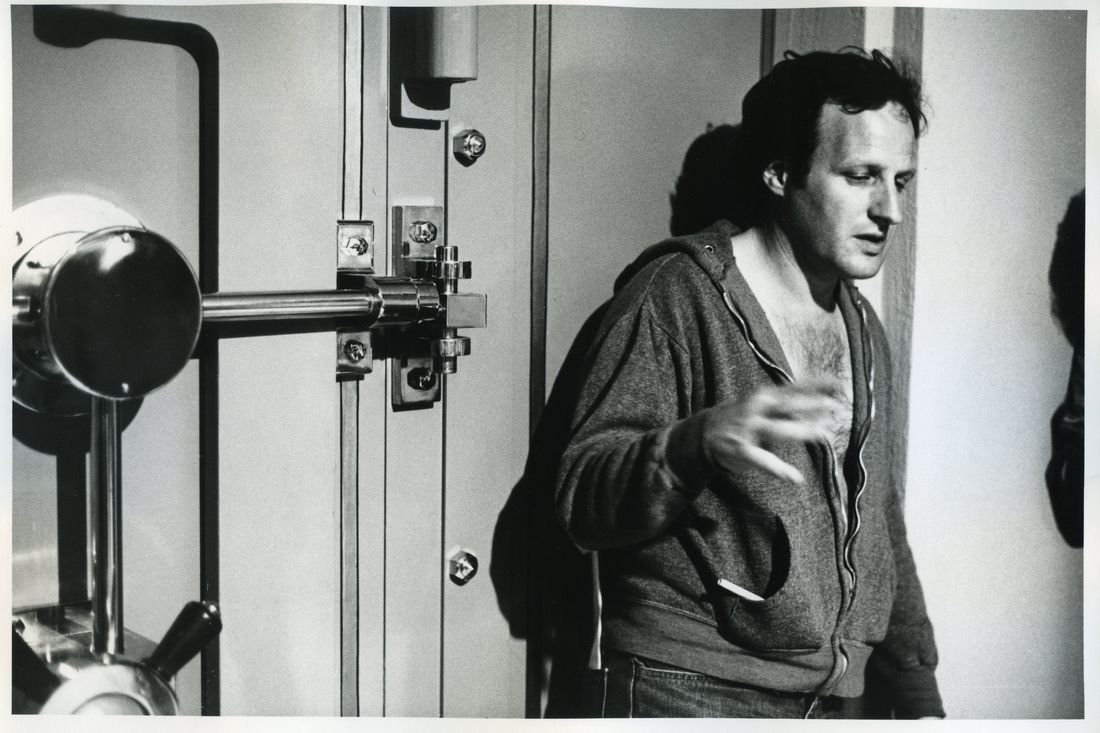

The contemporary criticism of the movie as more style than substance seems rather unfounded today. In watching Thief, it’s undeniable that we’re captivated by its nighttime compositions, its poignant melancholy, and the almost abstract robbery sequences filled with sparks and flames from steel vaults. However, there are deeper emotional, political, and narrative undertones at play. Frank expresses his feelings of exploitation to Leo, saying, “You’re making big profits from my work, my risk, my sweat.” The film vividly portrays these aspects, spending an uncommon amount of screen time on depicting how Frank and his partners prepare for their heists, gather and construct the necessary equipment, evade security systems and law enforcement; it then delves even deeper into showing the jobs themselves, as these men transport massive tools (authentic equipment used by professional thieves consulted for the film) into bank vaults and visibly tire themselves drilling holes in safes. Mann focuses on these scenes not only because they’re spectacle and hypnotic to watch but also to emphasize that this is genuine labor. By the time Frank takes a seat to survey his handiwork, we can feel his exhaustion, relief, and satisfaction of a job well done. And, inevitably, we share his anger when the fruits of his labor are taken from him.

On several occasions throughout the years, I’ve chatted with Mann regarding his projects. However, we hadn’t delved deeply into the specifics of Thief. With the arrival of this 4K version, it felt like the perfect moment to explore that topic more thoroughly. (Of course, I also inquired about Heat 2.)

The movie “Thief” was incredibly captivating for its time. When working on the visuals, I didn’t focus on replicating reality but rather on evoking specific feelings about Frank and his environment. I wanted viewers to experience Chicago not just as a two-dimensional city but as a complex, three-dimensional labyrinth that Frank navigates, decodes, and pursues within. To achieve this, I made use of the unique visuals that rainy Chicago offers. The wet streets at night, with their reflective surfaces and lights bouncing off them, gave the sensation of driving through a tunnel rather than on top of a surface. Consequently, we deliberately made the streets slick and shiny to enhance this perspective, and Frank’s black ’71 Eldorado added to this effect by reflecting the city lights as he moved through it.

The imagery of him navigating through a tunnel signifies his solitude, a key factor in his subsequent development of romantic feelings. To me, he embodies the literary archetype of the wild child; an individual shaped by unconventional circumstances, having spent most of his life confined within prison walls. From 18 years old until his late 30s, Frank was deprived of television and thus, found himself thrust into society in the 1980s, a culture he was unfamiliar with. He grappled with questions of identity, manners, values, and lifestyle, attempting to fit into this new world. To help him adapt, he gathered information from magazines and newspapers, trying to piece together the puzzle of what kind of person he should be, how he should behave, and what his life should look like. This included contemplating whether he needed a car, a house, or even a wife.

Similar to many prisoners I encountered, he utilized his prison time for reading, often delving into literature for a very practical reason: “Why shouldn’t I take my own life and put an end to this?” This question stemmed from encounters I had with inmates at Folsom while casting The Jericho Mile. Some of these prisoners would quote philosophers like Immanuel Kant, others espoused Marxist ideologies or combined Buddhism. They were seeking answers to questions like “What is my life to myself?” This was a man with only a sixth-grade education. When I attempted to cast another convict, he declined, stating, “No, man, I appreciate what you’re doing here and everything, but I can’t be in your movie.” When I asked why, he replied, “Because if I allowed myself to be in your movie, I would allow you to exploit the excess value of my negative karma.” He wasn’t joking. His response implied that he viewed his prison time as labor, and that he was serving time because he had accrued bad karma initially, i.e., he was caught.

The concept of labor permeates throughout the movie Thief, and it’s evident right from the start. The scene portrays that what Frank does is indeed hard work – the cumbersome machinery, the lengthy hours, and the endurance needed to drill a seemingly endless hole. Unlike typical heist movies, this one explicitly communicates: This is someone’s labor.

Interestingly, the planning and preparation for the heists in the movie mirror the process of filmmaking. The efficiency in researching, strategizing, bypassing security systems, timing the operation, and understanding the safe composition all echo the steps taken to create a movie. For instance, if the target were on the northwest side of Chicago, it would be optimal to execute the heist during a Cubs game since most cops would be at Wrigley Field. The specifics of the safe – its materials, lockbox location, and layered defenses – are all crucial details that require careful consideration, much like understanding the intricacies involved in film production.

Among those skilled individuals, what they do is indeed a labor, or work. The investigators who chase them, especially those who are exceptionally skilled, hold high regard for the clever thieves. This admiration doesn’t hinder their determination to apprehend them in any way. The character Charlie Adamson, portrayed as a detective in the movie, is known for saying to Frank, “Why do you always come off so stiff and uptight? We have ways here to smooth out the rough edges.” In reality, Charlie was the one who fatally shot Neil McCauley back in 1963. He shared with me the story of his encounter with McCauley, which served as the foundation for the relationship depicted in the film “Heat”.

In the film “Thief“, John Santucci, a man who had made a living as a professional burglar, provided me with valuable insights. The tools we used for our burglaries were not mere movie props; they belonged to John himself. Later on, he took on a recurring role in “Crime Story“. However, my most significant discovery through interacting with Santucci was an eye-opening revelation about how remarkably similar his life was to ours. He had family issues, dealing with two children and marital strife with his wife. I had to break free from the preconceived notions and stereotypes of what a burglar might be like. Who was he as an individual? What were his thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on life? These questions ultimately shaped the screenplay’s development.

Working alongside Santucci and Chuck Adamson on the film was quite an intriguing mix, as they were joined by individuals who had once been criminals and law enforcement officers. Can you imagine the dynamic of having such diverse personalities on a movie set? Well, let me tell you, it was nothing short of entertaining! They all had a history with one another, even though they were previously on opposite sides of the law. It was like a reunion, with jokes and banter that only insiders would understand. For instance, “You were such a pain back then when we raided Wieboldt’s store,” or “I’ve been trying to catch you for ages…” Such conversations took place in local bars over drinks. It was very much reminiscent of Chicago, and had a certain Brechtian feel, as Chicago was quite Brechtian at the time.

In simpler terms, one of the characters, who portrayed Leo’s right-hand man, was Bob Prosky’s character, the red-haired Bill Brown. Interestingly, this character was on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, though I’m unsure if they ever caught him, even after approximately 20 to 30 years since the movie’s release. Additionally, I collaborated with Dennis Farina in the film “Thief”, and we remained close friends until his unfortunate death some years later. During our work on a pilot and then the “Crime Story” series, he also worked with Santucci.

Could you explain how you describe Chicago as a Brechtian city?

In my youth during the 1950s, Chicago had a unique form of corruption that was democratic in nature. It was common for people to have a $20 bill concealed with their driver’s license when pulled over for running a red light, and this wasn’t exclusive to big corporations like Standard Oil of New Jersey. Similarly, aldermen had the ability to assign a certain number of jobs they could distribute, often no-show positions where working two days would result in being paid for five. If your street was not cleared after a snowstorm, you merely needed to call your alderman, and a plow would arrive within 30 minutes. There was an urban cynicism about the systems that existed, yet they functioned in a peculiar manner. Despite this, there were institutionalized racial biases, and Chicago was highly ethnically divided with a large Polish population, followed only by Warsaw. This led to Polish bakeries, Ukrainian establishments, Irish communities, and more. In essence, you could say that Chicago had some elements of the Brechtian city.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=watch?v=81L2BLtJT04

When discussing the memorable dialogue scene with Tuesday Weld at the coffee shop, one might wonder, “Is it possible to unfold an entire narrative within this single scene?” Given that film reels were once the medium, this particular scene clocked in at about ten minutes – a rare length for a dialogue-heavy sequence. In the midst of this feature film, I decided to delve deep and reveal Frank’s backstory right then and there. This choice carried some risk as I was unsure if it would resonate with the audience. However, it was crucial to illustrating Frank’s desperation and the intertwining of these two unanchored lives.

The specific booth I mentioned earlier is where I spent hours talking to the woman who later became my wife. During one car ride home, we stopped for coffee and our conversation went on for what felt like six hours in a coffee shop overlooking the Tri-State Tollway, although I’m not sure if it was a Fred Harvey’s at that time. The constant flow of cars reminded me of a bloodstream, symbolizing life’s continuous movement as people go about their journeys. It’s a metaphor for the multitude of lives passing us by, some moving towards us, others away from us, while we’re suspended above it all. In this booth, he expressed his deepest desires to her, leading him to make a fateful decision: He dropped a coin and promised to work with someone named Leo at a later time, which presents an ironic twist.

In this scene, what stands out to me is how both characters reveal their true selves. Caan exposes his vulnerability in a heartfelt manner, while she demonstrates her toughness. A memorable exchange occurs when she says, “Where were you in prison? Could you please pass the cream?” The dynamic between these two characters unfolds in an intriguing way as the story progresses. Is it all scripted?

For a rephrased version that reflects the writing process behind the dialogue:

The scene showcases each character’s true nature – one opening up with sincerity, and the other displaying resilience. The dialogue exchange where she inquires about his prison past while requesting the cream is one of those moments. The intricate dance between these characters unfolds in a captivating manner throughout, raising questions about its authenticity. However, it’s all scripted – this conversation serves as an exploration of their individual identities, with the goal of constructing something unique outside of societal norms and values. To keep the dialogue real and engaging, rather than becoming didactic or repetitive, it requires incorporating small, meaningful obstacles in the narrative flow to create a subtle yet significant sub-theme – “Here’s my past, can you join me in this unconventional journey we’re embarking on together.

As a fledgling TV writer in Los Angeles, I found solace and inspiration at Canter’s, an all-night diner where I spent countless hours sipping coffee and chatting with the waitstaff. A particularly memorable figure was Jeannie, a remarkable woman who juggled her job at Canter’s with playing poker in Gardino while supporting her two sons through medical school. She became a cherished friend, and even made an appearance on my shows as the one who asks, “What’s wrong with it?” when someone orders cottage cheese. I was so fond of Jeannie that I brought her onto the set from LA, where she continues to grace our sets with her presence.

In this critical scene, it’s evident that the characters are further developed and the plot progresses. Frank grapples with the decision of associating with organized crime, specifically the Chicago Outfit, due to his newfound desire for substantial heists following his realization about starting a family with a woman. This shift ultimately transforms the narrative into an expose on labor exploitation.

From my research and interviews with professional thieves, it’s understood that in Frank’s line of work during those years in Chicago, one of the key questions was: “What is the right balance between working independently and being connected to organized crime like the Outfit?” The reason for this is that if you choose to align yourself with the Outfit, you are bound to sell your stolen goods through their fences. This means you’ll only receive 30 cents for every dollar compared to the 50 cents you could get by dealing independently. Additionally, you might be asked to perform tasks you’re not comfortable with. Essentially, you don’t want to be controlled or employed by them.

As a cinephile, I’ve often pondered why American critics didn’t seem to grasp the political and ideological underpinnings of Thief. It might have been a matter of cultural differences, if you will. In Europe, however, the film was more readily accepted as a commentary on labor theory of value, with direct quotes like the ones in the movie supporting this interpretation.

It’s true that I spent time in Europe and went to film school there in the late ’60s. My film carries a clear left-leaning viewpoint, as I was deeply influenced by the political climate of that era. I wrote the script during the ’70s, and it wasn’t long before I started production in 1980, so many of the social issues from those decades were still fresh. It seems to me that Europeans tend to recognize the political undertones in drama more than Americans might be comfortable with.

What are your recollections of James Caan? During our commentary on the movie when it debuted on Blu-ray, it seemed like you two had a great rapport with him. In fact, it sounds like he was quite the collaborative actor, eager to grasp all aspects of his character to ensure authenticity in his performance – from speech nuances to the way he handled props. This real-life proficiency gave him a sense of confidence that shone through on screen. For instance, when portraying a scene where one might feel inner turmoil but must suppress it, and then find a way to exit an office having drawn a .45, his ability to convincingly execute these actions added an air of authenticity. It was clear that Jimmy could do everything his character could in real life, which greatly contributed to his performance.

A great movie has the power to captivate us emotionally; it feels like we’re part of the action alongside the actors. This emotional bond arises because we are intelligent beings who instinctively believe what we see on screen, due to its authenticity. In this case, James Caan, portraying Frank, becomes more than just an actor – he is Frank. The experiences and skills he showcases, such as safe-cracking training at Gunsite, Arizona under Jeff Cooper, add to this realism. Caan’s background as a college football player, athletic physique, and tough demeanor only enhance the believability of his character.

Are you asking for a film of mine that I wish more people would watch, appreciate, and discover? I’d recommend “The Insider.” This movie was particularly challenging for me as it required intense psychological depth. The story revolves around two hours and 45 minutes, portraying the tension and drama experienced by Jeffrey Wigand and Lowell Bergman.

In Lowell Bergman’s case, his life’s work is at risk, and he faces exclusion. For Jeffrey Wigand, the assault on him and his family leaves him near suicide. It’s a psychological warfare waged by adversaries, a mortal threat. The screenplay written by Eric Roth and I was designed to immerse the audience in that intensity. As a director, it presented a challenging opportunity for me to explore the depths of this experience cinematically. I felt it was a rewarding place to stretch myself, as I always find pushing boundaries to be healthy and enriching.

It appears that during the last 15 years or so, there has been a renewed interest in your films, including those that weren’t initially well-received. I personally find your movies excellent, but I wonder why they are resonating with audiences now? I don’t like to guess, but perhaps it’s because of the depth and complexity in your work. I strive not just to be a director who shoots films, but one who puts a great deal into each project. As a result, some of my films may offer more than just a simple two-hour escape; they might contain layers that invite viewers to relate on multiple levels. In the case of films like Heat and Insider, this is especially true due to their longer running times.

Is it possible for me to inquire about the current situation with Heat 2, as I’ve recently completed the screenplay and submitted the first draft?

In such a scenario, where would one submit a screenplay? In this instance, it was submitted to Warner Bros. Unfortunately, I’m unable to reveal any further details. However, it’s a thrilling project!

Read More

- 50 Goal Sound ID Codes for Blue Lock Rivals

- How to use a Modifier in Wuthering Waves

- Basketball Zero Boombox & Music ID Codes – Roblox

- 50 Ankle Break & Score Sound ID Codes for Basketball Zero

- Ultimate Myth Idle RPG Tier List & Reroll Guide

- Lucky Offense Tier List & Reroll Guide

- Ultimate Half Sword Beginners Guide

- ATHENA: Blood Twins Hero Tier List (May 2025)

- Watch Mormon Wives’ Secrets Unveiled: Stream Season 2 Free Now!

- ADA PREDICTION. ADA cryptocurrency

2025-03-27 20:55