Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that liquidity problems in payment networks can worsen after technical issues are resolved, driven by delayed behavioral shifts and persistent communication.

A multi-agent model demonstrates that eroded trust and ongoing merchant messaging can create peaks in liquidity risk even following system recovery.

While operational recovery of payment systems is often considered the primary goal following disruption, this can belie underlying behavioral dynamics that amplify liquidity risk. This is the central question addressed in ‘Modeling Trust and Liquidity Under Payment System Stress: A Multi-Agent Approach’, which demonstrates that aggregate withdrawal pressure can peak after technical restoration due to lingering distrust and persistent merchant signaling. Through a multi-agent model incorporating social contagion and bounded rationality, the research reveals how delayed behavioral responses create hysteresis and potentially exacerbate outflows even during the recovery phase. Does a sole focus on technical remediation therefore overlook critical psychological factors essential for building truly resilient payment infrastructures?

The Illusion of Resilience in Digital Payments

Despite their apparent sophistication, modern digital payment systems are acutely susceptible to disruptions that can swiftly manifest as payment outages. These vulnerabilities stem from the complex interplay of numerous interconnected components – including networks, servers, and software – any of which can become a single point of failure. While designed for seamless transactions, these systems often lack the robust redundancy and fail-safe mechanisms necessary to withstand unexpected surges in demand, malicious attacks, or even minor technical glitches. Consequently, even brief interruptions in service can cascade rapidly, halting payment processing and leaving both consumers and businesses unable to complete essential financial operations. The very efficiency that characterizes these systems ironically contributes to their fragility; streamlined processes often prioritize speed and cost-effectiveness over resilience, leaving little margin for error when faced with unforeseen challenges.

Digital payment systems, despite their convenience, are susceptible to disruptions that swiftly diminish public confidence. When outages occur, customers immediately begin to question the fundamental reliability of the entire financial infrastructure, moving beyond frustration with a single transaction to a broader concern about the security of their funds. This erosion of trust isn’t a fleeting reaction; it represents a fundamental shift in perception, where the assumed stability of digital finance is challenged. The speed at which trust can dissipate is particularly noteworthy, as modern payment networks rely heavily on consistent, uninterrupted service to maintain user confidence, and even brief interruptions can trigger significant doubt and apprehension among customers.

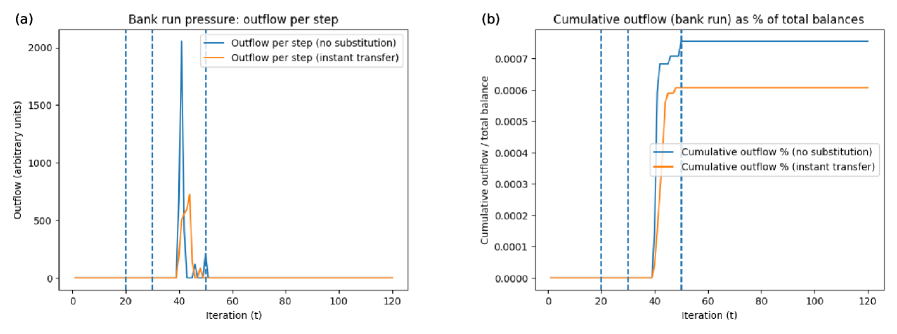

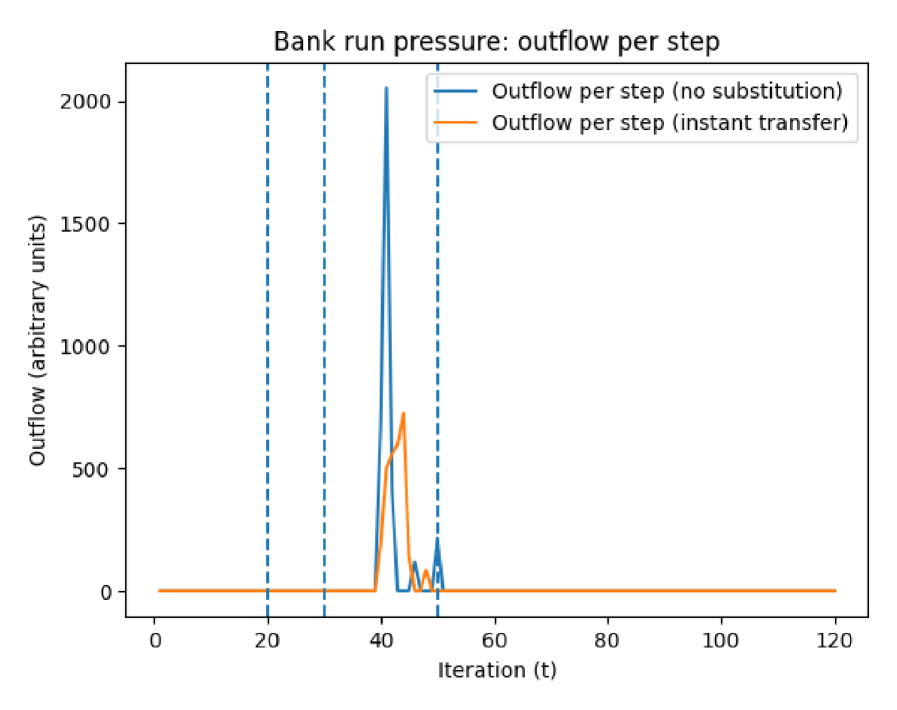

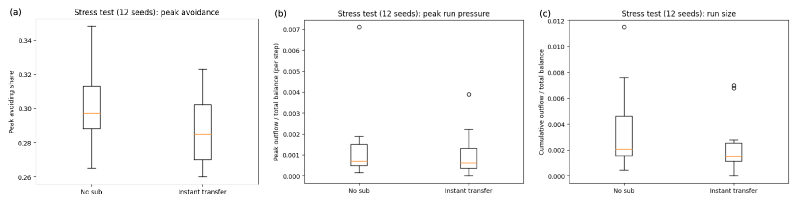

Simulations reveal that disruptions to digital payment systems trigger a surge in withdrawal requests, not during the outage itself, but surprisingly, after services are restored. This isn’t simply a matter of public anxiety; the research indicates a rational economic response where individuals, witnessing a system failure, proactively seek to safeguard their funds as a precaution against potential, future unavailability. The peak outflow of liquidity occurs as customers attempt to convert digital holdings into more tangible assets or alternative systems, creating a post-recovery rush that can strain even fully functional payment networks. This delayed withdrawal pressure highlights a critical vulnerability: restoring technical functionality isn’t sufficient; regaining user confidence and preventing a liquidity crisis requires addressing the underlying trust deficit created by the initial disruption.

Modeling the Herd: Agent-Based Simulations of Systemic Risk

An Agent-Based Model (ABM) is utilized to analyze customer responses to payment disruptions by representing each customer as an autonomous agent with defined behavioral rules. These agents interact within a simulated environment, allowing for the observation of emergent systemic effects. The ABM facilitates the modeling of heterogeneous customer characteristics and decision-making processes, including factors such as payment preferences, risk aversion, and social influence. By iteratively simulating agent interactions, the model captures the cascading effects of a disruption as it propagates through the customer base, providing insights into potential vulnerabilities and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. This approach contrasts with aggregate modeling techniques by explicitly representing individual behaviors and their impact on the overall system.

The agent-based model incorporates small-world network structures to represent the interconnectedness of individuals within the payment system. Unlike random or fully connected networks, small-world networks exhibit both high clustering and short average path lengths, meaning that individuals are more likely to be connected to their immediate peers but can also reach distant individuals through relatively few intermediaries. This topology is crucial for modeling systemic risk because it facilitates the rapid propagation of shocks – such as loss of confidence or payment failures – through the network via these social connections, creating potential contagion effects that would not be observed if agents were considered in isolation. The degree distribution of these networks typically follows a power law, implying the existence of a few highly connected nodes (“hubs”) which significantly influence network dynamics.

The Watts-Strogatz model generates small-world networks characterized by high clustering and short average path lengths. This is achieved by beginning with a regular ring lattice where each node is connected to its nearest k neighbors. Edges are then randomly rewired with a probability p, effectively creating long-range connections while preserving a significant degree of local connectivity. The resulting network structure accurately reflects observed patterns in social and technological networks, where individuals exhibit both strong ties within their immediate community and weaker, distant connections, facilitating rapid information propagation and influencing systemic behaviors.

The Ghosts in the Machine: Bounded Memory and Social Contagion

The model accounts for Bounded Memory by recognizing that customers do not possess, nor do they attempt to retain, a complete and accurate record of all past system performance data. Instead, customer perceptions are shaped by a limited and decaying recollection of recent experiences, weighted more heavily than those further in the past. This means that a single negative event can disproportionately influence current behavior, while a history of generally positive performance may not fully mitigate the impact of a recent failure. The implementation utilizes a decaying function to simulate this selective recall, prioritizing recent data points when assessing customer response to new system events and calculating overall trust levels.

Social contagion within a service network describes the propagation of negative perceptions and subsequent withdrawal of customers beyond those directly impacted by a service disruption. This effect is amplified by network structures and communication channels, where observed negative experiences of one customer influence the behavior of connected customers, even absent direct personal experience of the issue. The speed of this propagation is dependent on network density and the visibility of negative signals – such as online reviews or social media posts – leading to a disproportionate decrease in overall system usage. This cascading effect can significantly exceed the number of customers initially affected by the technical problem, creating a sustained reduction in system trust and potentially leading to long-term customer churn.

The Scar Variable within the model quantifies the cumulative impact of negative experiences on customer trust. This variable does not reset to zero following the resolution of an initial service disruption; instead, it persists, representing a lasting reduction in trust. The magnitude of the scar is determined by the frequency and severity of past negative events, weighted by a decay factor that simulates memory loss. Consequently, even after a system returns to full functionality, a non-zero scar variable increases the probability of future withdrawal, effectively lowering the threshold for subsequent negative perceptions to trigger further customer churn. This mechanism accounts for the observation that repeated or severe outages lead to sustained erosion of trust, independent of current system performance.

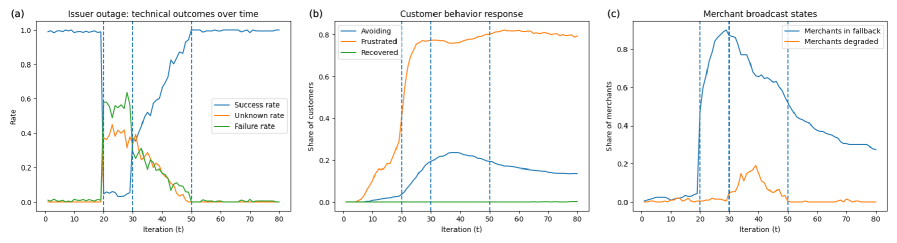

The Lingering Shadow: Why Recovery Doesn’t Feel Like Recovery

Simulations of financial system recovery consistently reveal a surprising phenomenon: withdrawal pressure doesn’t immediately subside upon the resolution of technical issues, but instead exhibits a delayed peak. Even as the underlying system stabilizes and functions normally, customers continue to initiate withdrawals at elevated rates for a period after restoration. This suggests that the perception of risk, and the behavioral response to it, lags behind actual system health. The simulations indicate that this delayed peak isn’t simply a momentary surge, but a sustained period of heightened withdrawal activity, potentially straining even a fully functional system and underscoring the importance of understanding the psychological component of financial stability. This behavior challenges the common assumption that technical recovery instantly translates to a return to normal financial flows.

The persistence of withdrawal pressure following system recovery isn’t solely a technical issue; it’s fundamentally shaped by a demonstrable behavioral lag in customer response. Simulations reveal that even after functionality is fully restored, individuals don’t instantaneously revert to their pre-disruption behavior, continuing to initiate withdrawals at a heightened rate for a considerable period. This challenges the common assumption that technical fixes automatically translate to immediate risk mitigation, as customer perception and response times don’t align with the speed of system recovery. The continued withdrawals, driven by lingering anxieties or a delayed recognition of stability, represent a critical factor in prolonging the period of elevated financial strain, demonstrating the crucial interplay between technical infrastructure and human behavioral patterns.

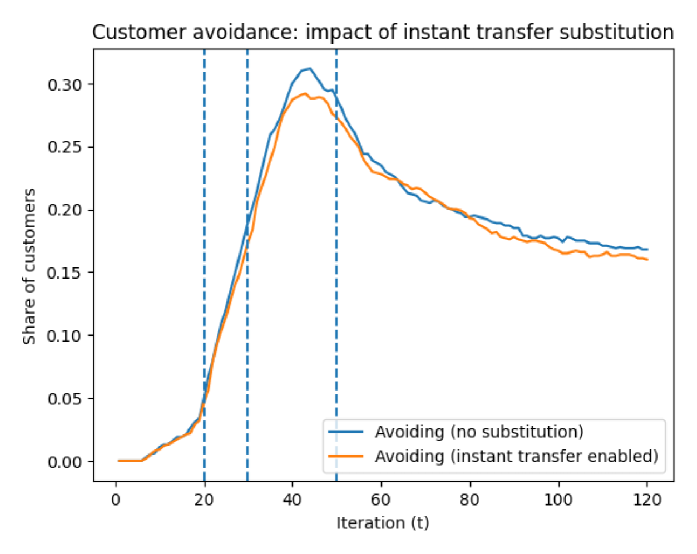

While the availability of alternative payment methods offers a potential buffer against peak withdrawal pressure following a system disruption, simulations reveal this mitigation is often incomplete. Though payment substitution can temporarily alleviate demands on the primary system, it doesn’t consistently translate into a reduction of overall withdrawals; customers frequently utilize both the restored primary system and alternative options concurrently. This suggests that behavioral factors – a reluctance to immediately revert to pre-disruption payment habits – limit the effectiveness of payment substitution as a long-term solution for managing cumulative financial outflow. The study indicates that simply providing options does not guarantee a return to baseline withdrawal patterns, highlighting the complex interplay between technical recovery and user behavior.

Beyond Uptime: Towards True Operational Resilience

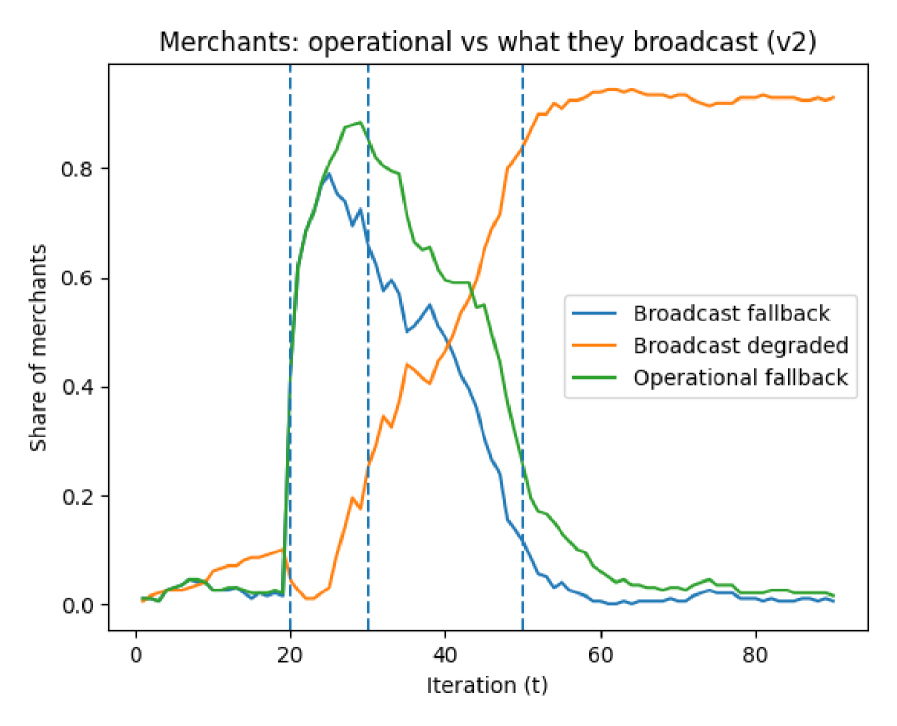

The propagation of information, particularly during times of financial stress, introduces a critical ‘rumor variable’ that significantly impacts systemic risk. Research demonstrates that even small operational disruptions can escalate into widespread crises not because of the initial problem’s severity, but due to how it’s perceived by the public and market participants. Negative rumors, fueled by uncertainty and readily shared through digital networks, can quickly erode confidence in financial institutions and the broader system. This erosion isn’t necessarily tied to fundamental weaknesses; rather, it’s a cognitive response to perceived instability. Consequently, managing these perceptions becomes as crucial as maintaining technical robustness, as unsubstantiated anxieties can trigger self-fulfilling prophecies of instability and amplify the impact of otherwise manageable events.

Digital finance institutions must prioritize preemptive communication to effectively manage perceptions during times of stress, as research demonstrates that rapidly spreading rumors can significantly exacerbate the impact of operational disruptions. A swift and transparent response to even minor incidents can counteract the formation of negative narratives and maintain customer confidence, preventing a localized issue from escalating into a systemic concern. These strategies involve proactively disseminating accurate information through multiple channels, actively monitoring social media for misinformation, and establishing clear lines of communication with stakeholders. By shaping the public’s understanding of their stability and capabilities, firms can build a crucial buffer against the cognitive biases and herd behavior that often amplify risk in the digital age, ultimately strengthening operational resilience beyond purely technical safeguards.

True operational resilience in digital finance extends far beyond simply maintaining technological uptime; it demands an understanding of the human element. Systemic stability isn’t solely a matter of robust infrastructure, but also of managing the cognitive biases and social dynamics that influence customer responses to disruption. A failure in service, even if rapidly addressed, can trigger cascading effects fueled by fear and distrust, rapidly eroding confidence if not preemptively addressed through transparent communication and proactive stakeholder engagement. Therefore, a truly resilient system integrates technical safeguards with a deep appreciation for behavioral economics and the principles of social psychology, acknowledging that customer perception and collective action are as critical to financial stability as the underlying technology itself.

The study meticulously models the cascading failures within payment systems, a predictably messy affair. It details how initial technical recovery isn’t the finish line, but merely a pause before the inevitable wave of behavioral contagion. This echoes a sentiment shared long ago by Carl Friedrich Gauss: “I would rather explain one fact than prove a thousand theories.” The researchers attempt to account for eroded trust and lingering merchant messaging – acknowledging that people don’t act like rational agents in a crisis. Of course, they don’t. This pursuit of modeling human irrationality within complex systems feels less like innovation and more like diligently documenting the ways everything new is just the old thing with worse docs. It’s a reminder that even the most elegant framework will eventually succumb to the realities of production.

What’s Next?

This modeling exercise, predictably, reveals the limits of modeling. The delay between technical recovery and the full manifestation of liquidity risk – driven by the slow churn of eroded trust – isn’t a bug in the system, but a feature of all systems involving human perception. Further refinement of agent-based models will undoubtedly yield more granular predictions, but the fundamental problem remains: every abstraction dies in production. The precise timing of panic will shift with each parameter tweak, yet the inevitability of some form of behavioral cascade won’t.

Future work should, therefore, focus less on predicting the precise moment of crisis and more on designing systems that are gracefully degradable during the inevitable period of psychological aftershock. The model highlights the persistence of merchant messaging as a key contagion vector. A fascinating, and likely underappreciated, avenue for research involves exploring the potential for ‘inoculation’ strategies – pre-emptive messaging designed to build resilience against negative sentiment.

Ultimately, this work is a reminder that operational resilience isn’t a technical problem with a technical solution. It’s a matter of managing the unpredictable, and accepting that everything deployable will eventually crash – the art lies in ensuring the wreckage is contained, and the rebuild is swift.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16186.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Itzaland Animal Locations in Infinity Nikki

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- James Gandolfini’s Top 10 Tony Soprano Performances On The Sopranos

- Elder Scrolls 6 Has to Overcome an RPG Problem That Bethesda Has Made With Recent Games

- RaKai denies tricking woman into stealing from Walmart amid Twitch ban

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Not My Robin Hood

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Unlocking the Jaunty Bundle in Nightingale: What You Need to Know!

2026-02-19 14:31