Nearly a century ago, Victor Frankenstein famously shouted, “It’s alive!” when he successfully brought a creature to life using assembled body parts. This moment not only marked a triumph over established scientific beliefs but also launched a lasting trend in movies – almost every film featuring a ‘mad scientist’ owes a debt to this iconic scene. While the 1931 Universal film, Frankenstein, directed by James Whale, shortened Mary Shelley’s original novel to just 70 minutes, the details left out have been thoroughly examined and reimagined in the many films that followed, ever since the monster first came to life.

As a longtime moviegoer, I’ve always been fascinated by adaptations of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. When James Whale brought the story to Universal over a century after its initial publication, it was a landmark moment. Now, Guillermo del Toro, a master of fantasy cinema, has finally delivered his own take – a lavish, big-budget epic he’s been developing for years, clearly deeply connected to the themes of Shelley’s novel. It got me thinking: comparing Whale’s classic to del Toro’s new vision, which Frankenstein film truly stands out as the best?

So, how do we categorize a Frankenstein movie? Mary Shelley’s novel has inspired countless films, from early silent shorts to recent comedies. While movies like Re-Animator, May, and Poor Things draw heavily from Shelley’s themes, we’re focusing on a simple rule for this list: the film must include the name “Frankenstein” (or a clear variation) and refer to either the doctor or his creation. Beyond that, filmmakers have been free to explore any themes they choose – horror, religion, romance, and everything in between. Here are 20 of the best Frankenstein movies made over the last century, celebrating Guillermo del Toro’s particularly insightful and complex take on Shelley’s work – a deeper dive than we’ve seen before in film.

20.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994)

Although many Frankenstein films are arguably superior to Kenneth Branagh’s dramatic take, it’s worth discussing because of its similarities to Guillermo del Toro’s version. Both directors stay true to the core story and characters of Mary Shelley’s novel, striving for a faithful adaptation. However, they also expand on the original material, pushing the narrative in ways Shelley didn’t. Branagh, for example, borrows the ending from James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein, creating a wildly energetic, though somewhat over-the-top, climax where the monster and his creator meet their fate. While some details from the book work well – Branagh’s Victor is suitably proud, and De Niro’s Monster is surprisingly thoughtful – others feel rushed or underdeveloped, particularly in the film’s second half. Produced by Francis Ford Coppola, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was conceived as a follow-up to a recent Dracula film, much like Universal’s 1931 classic. The film’s critical failure likely opened the door for Del Toro to secure funding from Netflix and attempt another adaptation.

19.

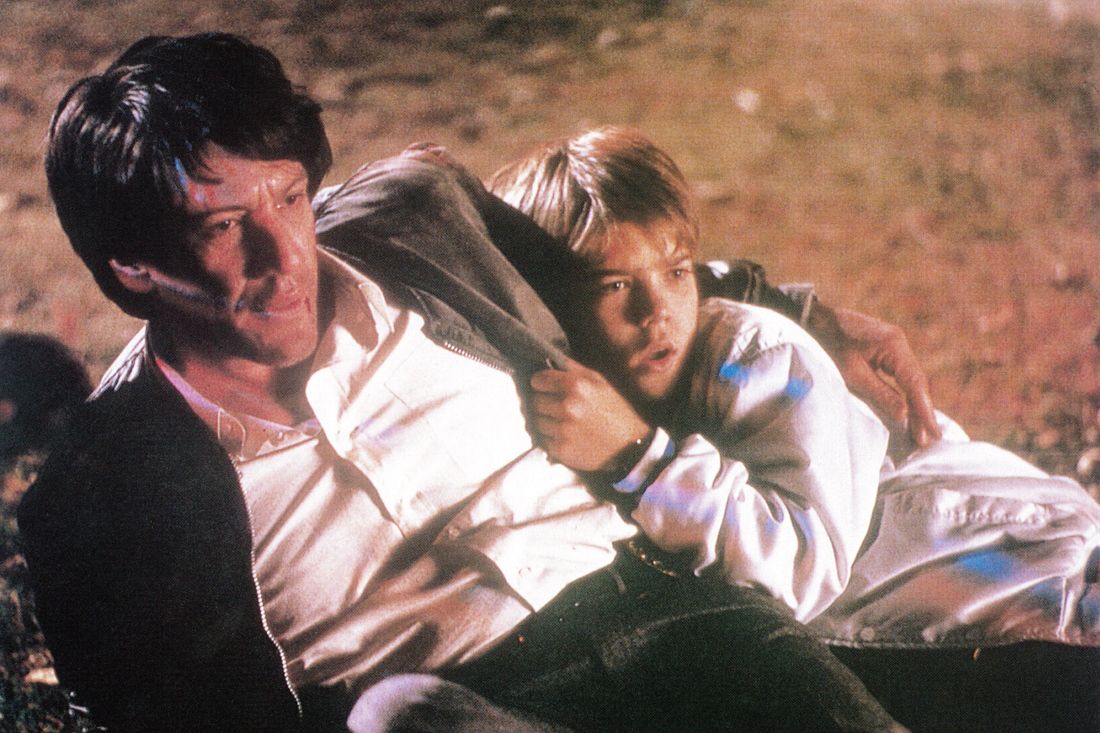

The Monster Squad (1987)

Over the last decade, with shows like Stranger Things popularizing a nostalgic trend, it’s become apparent that stories about kids having fantastical adventures often focus more on references and recreating a specific childhood feeling than offering something new. While The Monster Squad isn’t as polished as classics like E.T. or Gremlins, it has a certain appeal. The film cleverly pits children against iconic Universal monsters like Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster. Notably, it reimagines a touching scene from the original Frankenstein – the ‘Little Maria’ moment – by creating a sweet and innocent friendship between the Monster (played by Tom Noonan) and Phoebe, the protagonist’s little sister. This gives the Monster a connection and warmth that the original character lacked. The film even directly references the emotional farewell scene from E.T., creating a moment that’s both cheesy and surprisingly heartfelt.

18.

Depraved (2019)

Larry Fessenden, a filmmaker known for independent horror, started his directing career with the low-budget film No Telling, a rural take on the Frankenstein story that focused on relationships and animal testing. Almost 30 years later, he revisited similar themes in Depraved. This modern version is set in New York and begins with the murder of a young web designer whose brain is used to create a new being. This creation, named Adam, has no memory of the life that was sacrificed to give him existence. Depraved faced budget cuts during its production, but strong performances from David Call as the self-absorbed creator, Henry, and Alex Breaux as Adam, help overcome these limitations. The film thoughtfully explores the themes of Mary Shelley’s original Frankenstein, and uses visual effects to powerfully show the world through Adam’s newly awakened senses.

17.

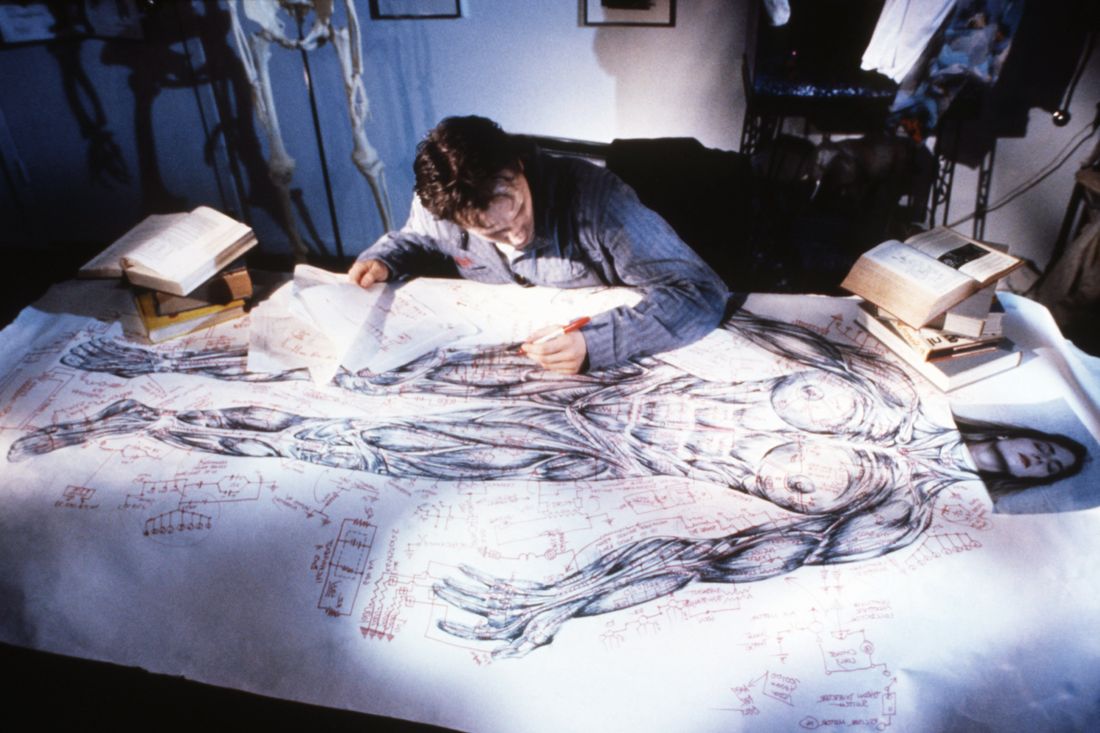

Frankenstein (2025)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein is the most ambitious adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel so far this century. The film, which runs over two and a half hours, skillfully combines overlooked parts of the original book with a respectful nod to the classic, gothic style of previous Frankenstein movies. Del Toro also uses the story to offer a thoughtful, if somewhat heavy-handed, message about how cruelty creates monsters. While visually impressive and detailed, the film feels a little predictable, as Del Toro has talked about making it for years. The movie quickly portrays Victor Frankenstein as self-absorbed, losing the internal conflict that made him a more complex character in the book. Oscar Isaac does his best with the role, but Jacob Elordi truly shines as the Creature, portraying his desire to experience life with a raw and touching vulnerability. Del Toro tends to immediately sympathize with his monsters, but this version overlooks the novel’s themes of disgust and the fear of unchecked power. It’s a long and captivating film, but ultimately too faithful to the source material to be truly memorable.

16.

Frankenhooker (1990)

Frank Henenlotter, known for his shocking and over-the-top horror films, made a splash with just a few movies, and his provocative title Frankenhooker is likely why this low-budget B-movie still gets attention decades later. The film follows Jeffrey Franken (played stiffly by James Lorinz), who attempts to bring his deceased fiancée Elizabeth (Patty Mullen) back to life after a lab accident. He does so by attaching her head to the bodies of various New York sex workers. Though intentionally shocking and immature, even before the gruesome special effects, Frankenhooker is driven by Jeffrey’s ambition and inner turmoil. However, once Elizabeth is resurrected, the film suffers from too much screen time with Lorinz and not nearly enough with Mullen.

15.

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943)

This film, the first team-up of Universal’s classic monsters, brings together the Wolf Man (Lon Chaney Jr.) and Frankenstein’s monster (Bela Lugosi, who played different roles in several of these films). It quickly hits all the familiar notes from their individual movies – the Wolf Man’s struggle for understanding before his transformations, and a scientist whose ambitious experiments worry the townspeople. It delivers exactly what fans expect, but little else. While the Universal monster movies were starting to lose their impact, this 73-minute film is a solid piece of classic horror, feeling more like a TV episode than a full-length movie. It’s a bit disappointing that the Wolf Man and Frankenstein’s monster don’t do much together, as they have great chemistry. They’re portrayed as kindred spirits, both struggling with their monstrous sides and clinging to their remaining humanity, rather than as enemies.

14.

Necropolis (1970)

This unusual Italian film isn’t often mentioned among the great Frankenstein movies, and for good reason: the Monster is only on screen for the first forty minutes. More than a horror film, it’s an art film that feels closer to European independent cinema, presenting a series of fragmented scenes depicting a society in decline – even featuring actress Viva (known for her work with Andy Warhol) lamenting her marriage to a man she calls the Devil. In one striking scene, the Monster (played by Bruno Corazzari) wanders through a room filled with red paintings reminiscent of Rothko, overwhelmed by the music. As he slowly learns to speak in a harsh, choppy voice, he begins to formulate his own ideas about what it means to be human – how hard it is to change things, how creativity is the only true freedom, and how humanity is still developing. Director Bruno Corazzari focuses on the Monster’s growing intelligence, showing how culture and morality shape his understanding of the world and lead him to a critical assessment of society’s problems.

13.

Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965)

Ishirō Honda, the director of Godzilla, created a lesser-known monster movie called Frankenstein Conquers the World (originally Frankenstein vs. Baragon). The film begins during World War II, where Nazis steal the still-living heart of Frankenstein’s monster and give it to scientists in Hiroshima. Fifteen years and the atomic bomb later, the monster is reborn as a wild boy who’s immune to radiation and grows rapidly into a giant. He soon finds himself battling Baragon, a horned monster from prehistoric times, but unlike Frankenstein, Baragon lacks any sense of humanity. While the human characters, including actor Nick Adams, don’t add much to the story – a common issue in monster movies – the monster himself is a visually impressive take on the classic Frankenstein character. He’s portrayed as a curious and defensive creature, struggling to survive and prove he’s not a threat. After fighting Baragon, he then faces a giant octopus that appears with no explanation. These battles highlight the monster’s connection to King Kong, sharing a similar simple empathy and impressive physical strength.

12.

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969)

As a huge horror fan, I’ve always known Hammer Films were a massive influence on British horror. They really popularized Gothic horror in the mid-20th century, and their take on classics like Frankenstein was unforgettable. They made seven Frankenstein movies, and the ones directed by Terence Fisher are the standouts. Even his fifth Frankenstein film still holds up – Peter Cushing is brilliantly unhinged as Baron Frankenstein, desperately trying to learn about freezing brains by blackmailing a young couple! It’s interesting because, twelve years after Cushing first played the role, Destroyed feels like Fisher was trying to restart the series, going back to the dark, unsettling feel and the tense home life from his 1957 film, The Curse of Frankenstein. Sadly, the story itself is a bit weak and shallow – apparently, the studio insisted on a really uncomfortable rape scene – which unfortunately holds back Fisher’s attempt to create a truly chilling atmosphere.

11.

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974)

Peter Cushing, playing the aging Baron Frankenstein, declares his work will never end, even when questioned by his eager assistant, Simon, at a Victorian mental asylum. While similar in quality to the film Destroyed, Monster From Hell has a noticeably somber tone, enhanced by its darker visuals. This time, Frankenstein is in charge of an asylum and faces a challenge to his authority. He creates a monstrous being using parts from murdered patients (with Simon’s help, as Frankenstein’s surgical skills are failing), all without drawing attention from the outside world. Despite dwindling resources signaling the end of Hammer’s most successful period, this final Frankenstein film from director Fisher and star Cushing serves as a fascinating and moving farewell to their iconic portrayal of Victor Frankenstein.

10.

Son of Frankenstein (1939)

Following the acclaimed films directed by James Whale, Son of Frankenstein introduces a new protagonist: Wolf Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone), the adult son of the original creator. Returning to his family’s estate, Wolf faces hostility from the local villagers and seeks to restore his father’s name. He teams up with the mysterious Ygor (Bela Lugosi), who leads him to his father’s laboratory, ultimately reviving the Monster. While visually striking with its unique set design, this film, which concludes the first decade of sound cinema, relies less on compelling atmosphere or character development and more on somewhat awkward dialogue. The movie is most engaging when Wolf attempts to hide the Monster – his ‘other’ family – from his proper, aristocratic relatives within the castle.

9.

Flesh for Frankenstein (1973)

Inspired by Roman Polanski, Paul Morrissey, who managed Andy Warhol’s Factory, decided to make a 3-D horror film, with a deal to create two movies funded by an Italian producer. Flesh for Frankenstein shares actors with its companion film, Blood for Dracula, notably Udo Kier as Baron Frankenstein. Isolated in his mansion with his wife (and sister) Katrin (Monique van Vooren), their peeping children, and his timid assistant Otto (Arno Jürging), the Baron attempts to create a new, superior race by building a male and female creature capable of reproduction. Beyond these troubling, almost fascist ideas, Frankenstein is fixated on the erotic side of life and death, specifically drawn to injuries and internal organs. Meanwhile, Katrin’s attraction to a handsome farmhand (Joe Dallesandro) threatens the Baron’s experiments. Morrissey deliberately breaks from traditional Frankenstein adaptations, fully embracing the disturbing eroticism and fascist undertones of creating new life. Though rough around the edges, this unusual 1970s film remains captivating due to its energy and unsettling nature.

8.

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948)

Making this comedy-horror film was surprisingly difficult, with several actors disliking the script and even skipping filming. Director Charles Barton deserves credit for managing the chaos. The film successfully blends a classic B-movie plot – Dracula wants to bring Frankenstein back to life using Lou Costello’s brain! – with the signature fast-paced comedy of Abbott and Costello. While the story has real tension, only the comedians are allowed to be funny; the monster actors play it completely straight. The climax isn’t a monster brawl, but Abbott and Costello using slapstick to escape a giant monster. It was a clever, if somewhat calculated, move to bring together Universal’s horror stars and revitalize their careers, and it ultimately works.

7.

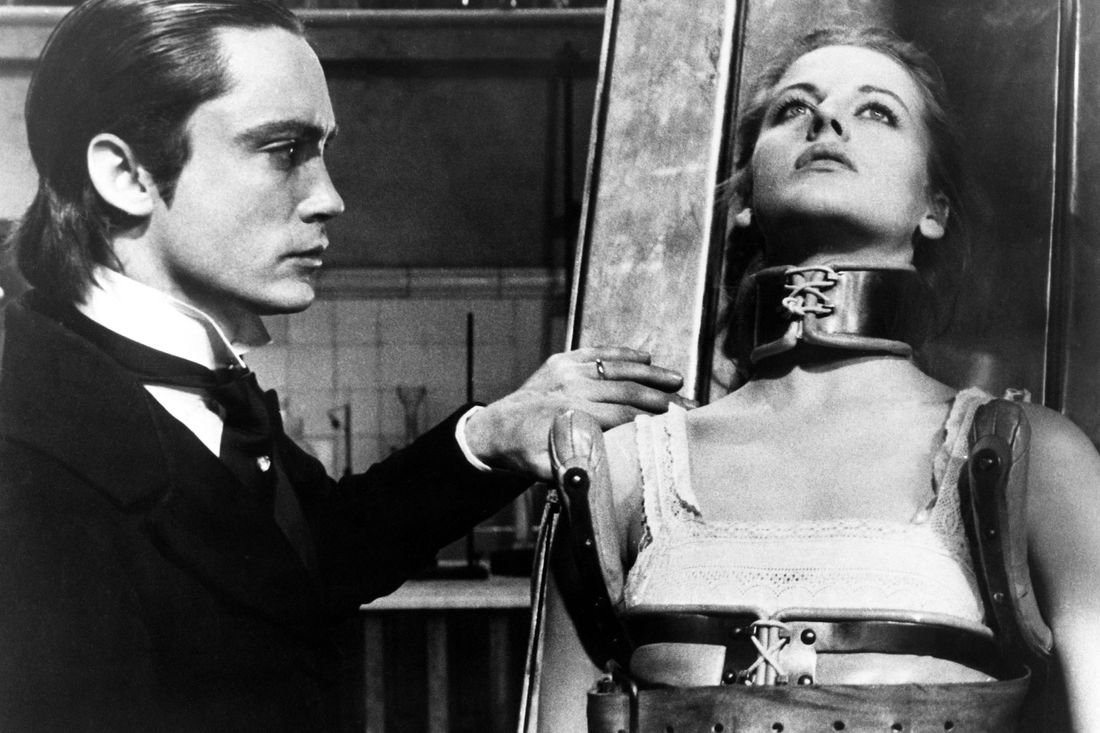

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

Hammer Films found consistent commercial success after releasing their first color film, a new and shocking take on the Frankenstein story for a post-Universal audience. While presented as original, the story of The Curse of Frankenstein was shaped by legal concerns as much as creativity: Mary Shelley’s novel was in the public domain, but Universal’s iconic film version was still protected by copyright. The film depicts a young Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) inheriting his family estate and forming a friendship with his tutor, Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart). His obsessive experiments and disregard for others—including his cousin and fiancée, Elizabeth (Hazel Court)—drive him to create a living monster, played in an early role by Christopher Lee. Director Terence Fisher crafted a strong and suspenseful Gothic horror film, drawing inspiration from both Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. Beyond its vibrant color and suggestive themes—common in Hammer films—The Curse of Frankenstein stands out by focusing on the unsettling home life of Frankenstein as a European nobleman. Victor displays a clear dislike for people, especially women, masking his dangerous experiments with claims of noble status and superior intelligence, which Elizabeth is forced to endure—a chilling and unpleasant portrayal of Frankenstein’s madness.

6.

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

It’s debatable whether Victor Erice’s slow-paced film about lost innocence during Franco’s rule in Spain can truly be called a Frankenstein film. While James Whale’s Frankenstein (in Spanish) is prominently featured at the beginning – shown to a village crowd including the young Ana Torrent – the characters mainly watch the story unfold rather than actively participating in it. However, a brief appearance of Frankenstein’s monster during the film’s climax, as Ana escapes her stifling family, directly echoes the murder of Little Maria in Whale’s original. Whether this monster is real or a figment of Ana’s imagination, the scene is powerfully moving, hinting that only a supernatural force can save Ana from the sadness and mystery surrounding her home and the oppressive atmosphere of Franco’s Spain. Erice contrasts the straightforward moral lessons often found in Frankenstein – about respecting God’s authority – with a story of adults who fail to offer their children understanding and kindness in a painful world.

5.

Frankenstein Created Woman (1967)

This is the fourth Frankenstein film from Hammer Horror, but only the third directed by Terence Fisher. After a nine-year break from the Baron’s experiments, Fisher delivers a shocking story about outcasts, the fear of execution, and a unique take on possession. The film centers on Baron Frankenstein, whose relentless ambition leads to tragedy for two young villagers: Hans (Robert Morris), the son of a known criminal, and Christina (Susan Denberg), an innkeeper’s daughter who has lived with disfigurement and shame. When both die, the Baron attempts a radical solution – he transplants Hans’ brain into Christina’s body, merging their identities and creating a vengeful, gothic figure. Driven by a shared thirst for revenge, this new being hunts down the upper-class bullies who destroyed their lives. Frankenstein Created Women is a particularly intense and unsettling entry in the series, cleverly examining Frankenstein’s inability to control his creations. The film powerfully shows how the trauma of violence can linger even after death, especially when consciousness is transferred to a different body – Christina becomes a creature of pure, unyielding rage.

4.

The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958)

Hammer’s second Frankenstein film, like many of their productions, saved money by reusing elements from other movies – notably sets from their recent Dracula film. However, this marked the beginning of a new approach in Terence Fisher’s Frankenstein series, shifting the focus from the traditional Monster to a different, doomed experiment. In this case, it’s Karl (Oscar Quitak), a paralyzed hospital assistant who agrees to have his brain transplanted into a healthy body (Michael Gwynn). Revenge shows a slightly more lighthearted side of Baron Frankenstein, thanks to Peter Cushing’s performance. The Baron, having escaped execution, disguises himself and works at a hospital to obtain the body parts he needs. His assistant, Hans (Francis Matthews), is eager to learn, and their shared lack of empathy makes Karl’s short life after the experiment even more tragic.

3.

Young Frankenstein (1974)

As a huge comedy fan, I always say Mel Brooks just gets what makes a great movie. His best, in my opinion, is Young Frankenstein, and it’s a lot like his other classics – he really understands the tropes of whatever genre he’s playing with, throws jokes at you non-stop, and clearly loves letting his actors have fun. Seriously, the cast – Marty Feldman, Teri Garr, Cloris Leachman, Madeline Kahn – everyone gets a moment to shine! But what makes Young Frankenstein special is how cleverly it plays with the Frankenstein story itself. Brooks lovingly recreates the look and feel of those old Universal films – the sets, the black and white photography, even entire scenes – but then injects it with this wild, over-the-top energy that highlights just how dramatic and heightened those original movies were. Gene Wilder is brilliant as Dr. Frankenstein, taking all that anxiety from previous versions and turning it up to eleven. And Brooks was so smart to make the Monster funny! Peter Boyle’s goofy expressions are just as captivating as any serious take on the character. It’s a risky move that totally pays off.

2.

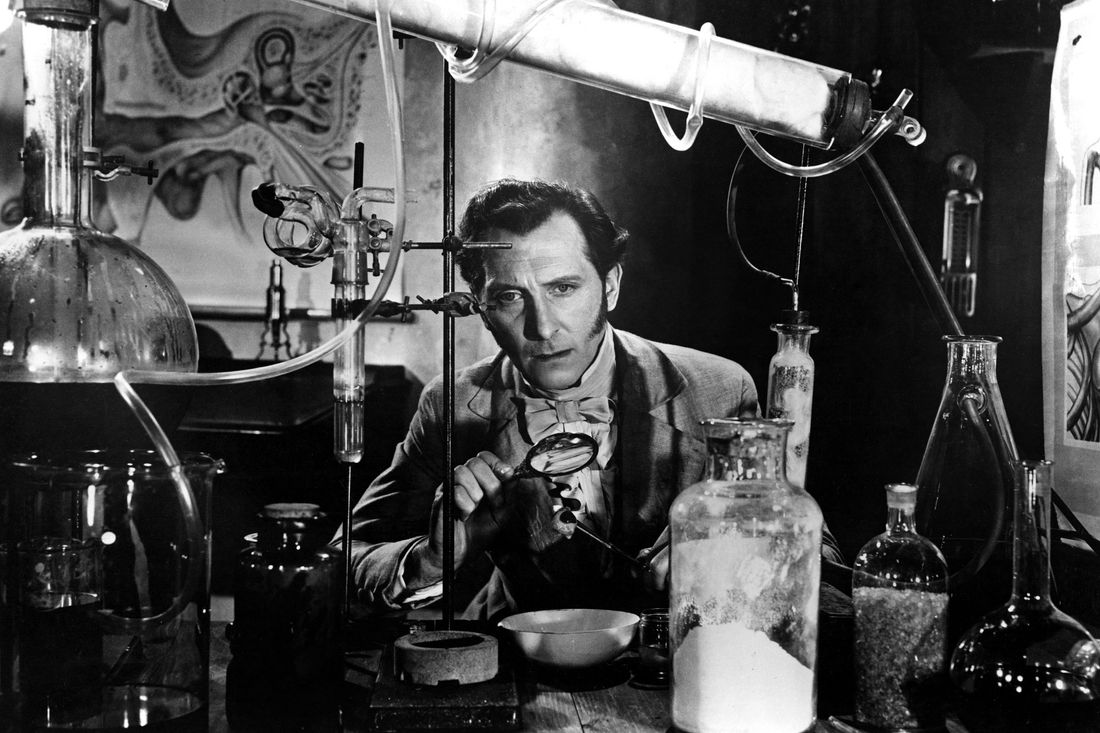

Frankenstein (1931)

The original Frankenstein film takes many liberties with Mary Shelley’s novel, opting for a visually dramatic and atmospheric approach rather than a faithful recreation of the story. Director James Whale emphasizes striking sets and gothic imagery, resulting in a 70-minute film that remains the most iconic cinematic interpretation of the tale – focusing on the man who creates the Monster, not the Monster himself. The film simplifies the creature, stripping away his intelligence, isolation, and complex motivations. Instead, Boris Karloff delivers a powerfully physical performance as a redesigned, instantly recognizable Monster brought to life with dramatic use of lightning and a hilltop castle setting. While this Monster lacks the thoughtful inner life found in Shelley’s novel, his brooding presence effectively contrasts with the energetic and obsessive nature of his creator, Henry Frankenstein. Beyond the Monster’s brief and unfortunate encounters with society, the film subtly highlights the complicated idea of creation as a form of parenthood, and the anxieties surrounding bringing a “child” into the world outside of traditional family structures. A key scene shows Henry’s father eagerly awaiting a legitimate heir, juxtaposed with a close-up of Henry’s troubled thoughts about the monstrous “son” he has already created.

1.

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein delivers everything you’d expect from a great Frankenstein movie, and arguably does it better than any film in the last ninety years. It explores the scientist’s dangerous ambition to conquer death, the Monster’s experiences with both kindness and prejudice, and even hints at a complex relationship between the scientist and his creation. There’s a fascinating undercurrent suggesting the scientist is trying to steer Frankenstein away from his wife and towards creating a companion for the Monster. Beyond its compelling story – all packed into a fast-paced 75 minutes – Bride is visually and aurally stunning, filled with dramatic lighting and the sounds of crackling electricity. The climax, where the Bride (played brilliantly by Elsa Lanchester, who also appears as Mary Shelley in the opening), comes to life and immediately rejects her existence, is particularly powerful. Overflowing with emotion and intensity, Bride of Frankenstein is a remarkably original and respectful adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel, and remains unmatched in its imaginative scope.

Read More

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- Heated Rivalry Adapts the Book’s Sex Scenes Beat by Beat

- EUR INR PREDICTION

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

2025-10-20 22:59