Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals a surprising mathematical link between the established field of spatial statistics and the rapidly evolving world of large neural networks.

This review demonstrates the equivalence of Kriging and Gaussian Processes to infinitely wide neural networks, highlighting a deep connection through the Neural Tangent Kernel.

Despite their distinct origins, spatial statistics and modern machine learning increasingly converge, yet a formal understanding of their relationships remains elusive. This paper, ‘The Connection between Kriging and Large Neural Networks’, explores this intersection, demonstrating a mathematical equivalence between Kriging – and its probabilistic counterpart, Gaussian Processes – and infinitely wide neural networks via the Neural Tangent Kernel. This surprising link reveals that techniques from spatial statistics can be recast as fundamental properties of large neural networks, offering new perspectives on interpretability and generalization. Could this bridge between statistical rigor and scalable machine learning unlock more robust and spatially aware artificial intelligence systems?

The Erosion of Linearity: Spatial Modeling’s Foundational Challenges

Conventional spatial interpolation techniques, prominently including Kriging, frequently operate under the assumptions of Gaussian distributions and linear relationships between variables. However, many natural phenomena exhibit non-Gaussian behavior and complex, non-linear dependencies. This reliance on simplifying assumptions can introduce significant limitations when applied to real-world datasets characterized by skewness, multimodality, or abrupt transitions. For instance, environmental processes like pollutant dispersal or disease spread often defy linear modeling due to factors like threshold effects, feedback loops, and spatial heterogeneity. Consequently, predictions derived from these traditional methods may underestimate uncertainty and fail to accurately represent the true spatial variability, potentially leading to misinformed conclusions and ineffective management strategies.

Traditional spatial interpolation techniques, while valuable, frequently encounter limitations when applied to datasets exhibiting non-linear patterns and inherent uncertainty. The reliance on assumptions of statistical normality and linear relationships can lead to substantial inaccuracies in predictive modeling, particularly in complex environmental or socio-economic scenarios. Consequently, decisions informed by these flawed predictions – ranging from resource allocation to risk assessment – may prove ineffective or even detrimental. This is because the true spatial process governing the phenomenon under investigation often deviates from the idealized conditions required by these methods, resulting in an underestimation of potential errors and a compromised understanding of the landscape. Addressing this requires innovative approaches that can accommodate complexity and quantify uncertainty more realistically.

Accurately representing the complexities of spatial phenomena demands a shift away from simplistic modeling approaches. Traditional methods frequently presume a smooth, linear relationship between observations, yet natural processes are rarely so predictable. The fundamental difficulty isn’t merely estimating spatial values, but rather, constructing a model that faithfully captures the process generating those values without being constrained by assumptions of normality or linearity. This requires flexible techniques capable of accommodating abrupt changes, complex interactions, and inherent uncertainty – methods that acknowledge the potential for non-Gaussian behavior and allow the data itself to inform the model’s structure. Consequently, research focuses on developing algorithms – such as geographically weighted regression, random forests, and Gaussian processes with non-parametric kernels – that prioritize data-driven adaptation over rigid parametric forms, ultimately providing a more realistic and reliable representation of the underlying spatial dynamics.

Gaussian Processes: A Probabilistic Foundation for Spatial Understanding

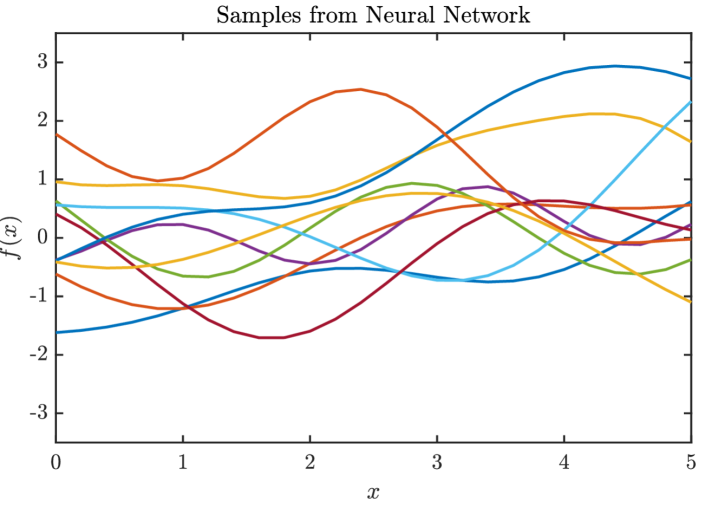

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) fundamentally differs from traditional regression techniques by directly modeling a distribution over possible functions that fit the observed data. Instead of estimating a single function, GPR defines a probability distribution over the space of functions, allowing it to quantify uncertainty in predictions. This is achieved by assuming that the function values at any set of input locations follow a multivariate Gaussian distribution. The mean of this Gaussian represents the expected function value, while the covariance describes the correlation between function values at different input locations. This probabilistic approach enables GPR to provide not only point predictions but also confidence intervals, reflecting the uncertainty associated with those predictions and making it particularly suitable for applications requiring robust uncertainty quantification and exploration of model uncertainty. f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x,x'))

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) utilizes kernel functions to define a covariance function, which quantifies the similarity between data points and thereby captures underlying smoothness and correlation in the data. The Squared Exponential Kernel, a common choice, assumes that points closer in input space are more correlated than those further apart, effectively imposing a smoothness prior on the function being modeled. This allows GPR to make predictions not as single point estimates, but as probability distributions, providing a measure of uncertainty alongside the predicted value; the variance of this distribution reflects the confidence in the prediction, decreasing as data density increases and the kernel indicates higher similarity between the prediction point and observed data. The kernel’s parameters are learned from the data, allowing the model to adapt to the specific correlation structure present in the dataset.

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) represents a generalization of Kriging, a geostatistical method for interpolation and prediction. Specifically, GPR can be mathematically defined as the Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) estimate within the Kriging framework. Traditional Kriging relies on linear combinations of observed data, whereas GPR, by employing kernel functions, introduces non-linearity into the model. This allows GPR to capture more complex spatial patterns and relationships than standard Kriging. The MAP estimation within GPR optimizes model parameters to maximize the posterior probability given the observed data, effectively incorporating prior beliefs about function smoothness and correlation, leading to improved predictive performance and uncertainty quantification in scenarios with non-linear data relationships.

The Allure of Scale: Neural Networks and the Infinite Width Limit

Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) provide a computationally efficient alternative to Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) by approximating its functionality in the limit as the network width-specifically, the number of hidden units-approaches infinity. While GPR offers a robust but computationally expensive approach to regression due to its O(n^3) scaling with data size n, MLPs, when sufficiently wide, can achieve comparable performance with a computational complexity that scales more favorably. This approximation allows for the application of GPR-like methods to larger datasets where traditional GPR becomes intractable, offering a scalable solution without sacrificing the probabilistic outputs characteristic of Gaussian Processes.

The Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) provides a theoretical framework demonstrating the equivalence between wide, properly initialized, and trained multilayer perceptrons and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR). Specifically, as the width of the neural network-the number of hidden units-approaches infinity, the network’s training dynamics become increasingly governed by kernel regression with the NTK as the kernel. This means the function learned by the neural network converges to the same function that would be learned by a GPR model using the NTK. The NTK is computed by evaluating the gradient of the neural network’s output with respect to its parameters at initialization, and it remains approximately constant during training with infinitesimal learning rates, thus simplifying the analysis of network behavior and providing a connection to established kernel methods.

Comparative rank tests were conducted to assess the predictive performance similarity between Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) approaching the infinite width limit. Using a Squared Exponential kernel, the rank test resulted in a p-value of 0.63, indicating a substantial degree of agreement between the two methods. Further increasing the similarity, MLPs employing a cosine activation function yielded a p-value of 0.91 in the same rank test. These results were obtained using neural networks with 200 hidden units, a configuration designed to effectively approximate the GPR limit distribution, suggesting that sufficiently wide networks can closely mimic the behavior of GPR models.

Beyond Points and Areas: Functional Data Analysis and Depth-Based Spatial Modeling

Functional Data Analysis offers a distinctive approach to understanding spatial phenomena by moving beyond the analysis of discrete points or areas and instead treating data as continuous curves or functions. This paradigm shift allows researchers to capture the complete trajectory of a variable across space or time, revealing nuances often lost in traditional methods. Instead of simply noting a value at a specific location, FDA examines the shape of the spatial function itself – its peaks, valleys, and overall form – enabling a more holistic understanding of the underlying processes. This is particularly useful when dealing with irregularly sampled data or when the rate of change between observations is crucial, as FDA can effectively model and analyze these continuous signals, providing a richer and more detailed representation of spatial variability than point-based statistics alone.

The concept of depth in functional data analysis offers a novel approach to understanding spatial relationships by ranking spatial functions based on their centrality within a dataset. Unlike traditional spatial statistics focused on single points or areas, depth-based methods assess the ‘depth’ of a function – essentially, how far ‘inside’ the overall distribution of functions it lies. A function with a high depth is considered typical and representative of the spatial process, while those with low depth are outliers or unusual patterns. This allows researchers to identify influential spatial features, detect anomalies, and compare the relative importance of different spatial functions without relying on strict parametric assumptions. By quantifying the centrality of spatial functions, depth provides valuable insights into the underlying spatial structure and enables a more nuanced understanding of complex spatial phenomena, revealing relationships that might be obscured by conventional methods.

The integration of Functional Data Analysis (FDA) with geostatistical methods like Kriging presents a robust strategy for modeling intricate spatial phenomena. Traditional spatial analysis often treats discrete data points, whereas FDA allows for the analysis of continuous spatial functions – representing phenomena as curves rather than isolated values. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with irregularly sampled data or processes exhibiting continuous change. By leveraging FDA, spatial modeling can move beyond simply predicting values at specific locations; it can characterize the overall shape and behavior of spatial functions, revealing nuanced patterns and relationships. Combining this with Kriging, a technique for estimating values across space, allows for not only prediction but also a quantification of uncertainty associated with those predictions, providing a more complete understanding of spatial variability and enabling informed decision-making in fields ranging from environmental science to epidemiology.

The Path Forward: Sparse Efficiency and the Future of Spatial Prediction

While Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) provides a robust framework for spatial prediction, computational demands often limit its scalability. Alternatives like Relevance Vector Machines (RVM) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) offer increased efficiency by focusing on a sparse subset of training data, but this comes at a conceptual cost. Unlike GPR’s probabilistic foundation which inherently quantifies uncertainty, RVM and SVM operate as deterministic models, potentially sacrificing the ability to reliably assess prediction confidence. Specifically, these methods prioritize model parsimony – identifying the most relevant data points – through techniques that can diverge from the Bayesian principles underpinning GPR. This trade-off between computational efficiency and probabilistic rigor represents a key consideration when selecting a spatial modeling approach, particularly as datasets grow in size and complexity.

Traditional Gaussian process regression (GPR), while powerful, faces computational bottlenecks when applied to large spatial datasets due to its cubic scaling with data size. Consequently, alternative methods prioritizing sparsity and efficiency have emerged as promising solutions. These techniques, such as Relevance Vector Machines and Support Vector Machines, aim to approximate the underlying spatial relationships using only a small subset of the available data, drastically reducing computational demands. By focusing on the most influential data points and discarding redundant information, these sparse methods facilitate scalable spatial modeling, enabling analyses that were previously intractable. This shift not only enhances computational feasibility but also potentially improves model generalization by preventing overfitting to noise in massive datasets, opening avenues for real-time applications and exploration of previously inaccessible spatial phenomena.

Advancing spatial modeling necessitates a convergence of techniques, and future investigations should prioritize the integration of sparse methods – like Relevance Vector Machines and Support Vector Machines – with methods based on Fractional Differential Analysis (FDA). Such a synthesis promises to overcome the limitations of individual approaches by capitalizing on their respective strengths; probabilistic models excel at quantifying uncertainty, while sparse learning offers computational efficiency for large datasets. Exploring hybrid architectures – combining the predictive power of one with the scalability of the other – could unlock entirely new possibilities for modeling complex spatial phenomena. This includes developing algorithms that seamlessly switch between probabilistic and sparse representations based on data characteristics, and designing novel regularization techniques that promote both sparsity and probabilistic coherence, ultimately leading to more robust and computationally feasible spatial predictions.

The demonstrated equivalence between Kriging and infinitely wide neural networks suggests a fundamental truth about system evolution. Just as spatial statistics, embodied by Kriging, matured over decades, modern machine learning paradigms are merely revisiting established principles through a different lens. Vinton Cerf aptly stated, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This ‘magic,’ in this context, is the rediscovery of mathematical foundations-the realization that seemingly disparate fields converge under the umbrella of consistent principles. The article highlights that incidents, or apparent deviations, are not failures but steps toward a more complete understanding of the underlying system – a system that, like all others, ages and adapts within the medium of time.

The Long View

The demonstrated equivalence between Kriging and infinitely wide neural networks is not a convergence, but a revelation of shared ancestry. Both approaches, it appears, are attempting to solve the same fundamental problem – interpolation in a high-dimensional space – but have traversed divergent paths of implementation. Versioning, in this context, is a form of memory; the neural network, constrained by optimization, forgets the full Gaussian Process potential, while the spatial statistic retains it, albeit at a computational cost. The arrow of time always points toward refactoring-toward more efficient representations of the underlying truth.

A natural extension of this work lies in understanding the limitations imposed by finite width. Where does the approximation break down, and what novel regularization techniques might preserve the benefits of the infinite-width regime in practical applications? Furthermore, the connection to spatial statistics suggests a fruitful avenue for incorporating prior knowledge – geological formations, weather patterns – directly into neural network architectures, moving beyond purely data-driven approaches.

Ultimately, the paper highlights a persistent truth: all models are imperfect representations. The challenge isn’t to build a perfect model-that is an asymptotic ideal-but to build models that degrade gracefully. The elegance of finding equivalence isn’t in solving a problem, but in reframing it, revealing the underlying symmetries that endure even as implementations decay.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.08427.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

- Gold Rate Forecast

2026-02-10 22:01