Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study systematically tests the robustness of Fourier Neural Operators across a range of partial differential equations, revealing common failure points and highlighting areas for improvement.

Researchers identify spectral bias and compounding errors as key factors limiting generalization in neural operator-based PDE solutions.

Despite recent advances in scientific machine learning, the robustness of neural operator approaches to solving partial differential equations remains poorly understood, particularly when faced with realistic distributional shifts. This paper, ‘Forcing and Diagnosing Failure Modes of Fourier Neural Operators Across Diverse PDE Families’, presents a systematic stress-testing framework evaluating Fourier Neural Operators across five PDE families, revealing vulnerabilities such as spectral bias and compounding errors. Our large-scale evaluation-encompassing 1,000 trained models-demonstrates that even moderate shifts in parameters or boundary conditions can dramatically inflate errors, while resolution changes primarily affect high-frequency modes. These findings provide a comparative failure-mode atlas, but how can we design operator learning architectures and training strategies to systematically address these identified weaknesses and achieve truly generalizable performance?

Bridging the Gap: From Discretization to Continuous Representation

A vast array of phenomena in science and engineering, from fluid dynamics and heat transfer to electromagnetism and quantum mechanics, are fundamentally governed by partial differential equations PDEs. These equations don’t describe values at discrete points, but rather relationships between functions across continuous spaces-imagine mapping temperature across a heated plate or airflow around an aircraft wing. Consequently, finding solutions requires understanding behavior not just at specific locations, but everywhere within a defined domain. This inherent continuity presents a significant challenge, as real-world implementation often demands representing these continuous functions in a way computers can process, necessitating approximations and often substantial computational resources to achieve accurate results. The core difficulty lies in bridging the gap between the continuous nature of PDE solutions and the discrete world of digital computation.

Conventional numerical techniques, such as finite element analysis, tackle continuous problems by breaking down the infinite-dimensional solution space into a finite number of discrete elements. While effective, this discretization inherently introduces approximation errors; the true solution, existing within the continuous space, is only ever approximated by a solution defined on these discrete elements. Moreover, the computational demands escalate significantly as finer discretizations – necessary for greater accuracy – require exponentially more elements and, consequently, increased memory and processing power. This trade-off between accuracy and computational cost is a fundamental limitation of these methods, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional problems or those requiring real-time solutions. The granularity of the discretization directly impacts both the fidelity of the result and the resources required to obtain it, creating a persistent challenge for scientists and engineers.

Operator learning represents a significant departure from conventional approaches to solving problems governed by partial differential equations. Instead of focusing on approximating solutions within a discretized space, this emerging field directly learns the relationship – the operator – that maps an input function to its output function. This bypasses the need for computationally expensive mesh generation and approximation inherent in methods like finite element analysis. By treating the entire solution operator as the object of learning, algorithms can potentially generalize to unseen scenarios and achieve solutions with greater efficiency and accuracy. This function-to-function mapping, often implemented through neural networks, allows for a continuous representation of the solution, circumventing the limitations imposed by discrete approximations and opening new avenues for tackling complex scientific and engineering challenges.

Unveiling the Fourier Neural Operator: A Spectral Approach

The Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) utilizes the spectral representation of functions, transforming data from the spatial domain to the frequency domain via the Fourier transform. This allows the network to learn the solution operator – the mapping from input function to output function – directly in the spectral space. Specifically, FNO decomposes functions into their constituent frequencies, enabling the network to identify and learn relationships based on these frequency components. The core operation involves applying learned filters in the Fourier domain, effectively performing convolutions in the spectral space, and then transforming the result back to the spatial domain via the inverse Fourier transform to obtain the solution. This approach differs from traditional neural networks that operate on grid-based representations, and instead focuses on the underlying functional relationships expressed as \hat{u}(k) = \mathcal{N}(\hat{f}(k)) , where \hat{u} and \hat{f} represent the Fourier transforms of the solution and input functions, respectively, and \mathcal{N} denotes the learned neural network operator.

The Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) achieves efficient representation of continuous functions by leveraging the properties of the Fourier transform, which decomposes a function into its constituent frequencies. This spectral representation allows the network to directly learn relationships between different frequency components, effectively capturing long-range, global dependencies within the data that are often difficult for spatially local operations, such as convolutional layers, to model. Because the Fourier basis is often sparse for smooth functions, FNO requires significantly fewer parameters compared to traditional deep learning architectures operating in the spatial domain to achieve comparable or superior performance. This reduction in parameters is achieved by learning a mapping in the frequency domain \hat{u}(k) = F(u(x)) where u(x) is the function in physical space and \hat{u}(k) is its Fourier transform, rather than learning a pointwise mapping in the spatial domain.

Traditional deep learning architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and fully connected networks, struggle with partial differential equation (PDE) solving due to the need to discretize both space and time, leading to high computational cost and memory requirements as resolution increases. These methods often fail to generalize well to unseen data with different boundary conditions or forcing functions. The Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) circumvents these limitations by learning the solution operator directly in the spectral domain; this allows it to capture global dependencies without requiring a large number of parameters dependent on spatial discretization. Consequently, FNO exhibits improved efficiency – achieving comparable or superior accuracy with significantly fewer trainable parameters – and enhanced scalability to higher resolutions compared to conventional deep learning approaches for PDE solving.

Stress Testing the Limits: Assessing Robustness and Generalization

To evaluate the robustness of the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO), a series of stress tests were conducted involving three primary perturbation types. Parameter shifts involved alterations to the coefficients within the governing partial differential equations (PDEs). Resolution extrapolation tested the model’s performance when predicting solutions at grid resolutions higher than those used during training. Boundary condition shifts introduced deviations from the training data’s boundary conditions. These tests were designed to move the input data outside of the training distribution and assess FNO’s ability to generalize to unseen scenarios and maintain predictive accuracy under non-ideal conditions.

Stress testing of the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) deliberately employed inputs outside the range of data used during its training phase. This methodology was implemented to evaluate the model’s generalization capability and its capacity to accurately predict outcomes for scenarios not previously encountered. By exposing FNO to out-of-distribution data – encompassing parameter variations, altered resolutions, and modified boundary conditions – researchers aimed to quantify performance degradation and identify limitations in the model’s ability to extrapolate beyond its learned data manifold. This approach provides insights into the robustness of FNO and its suitability for real-world applications where inputs may deviate from the training dataset.

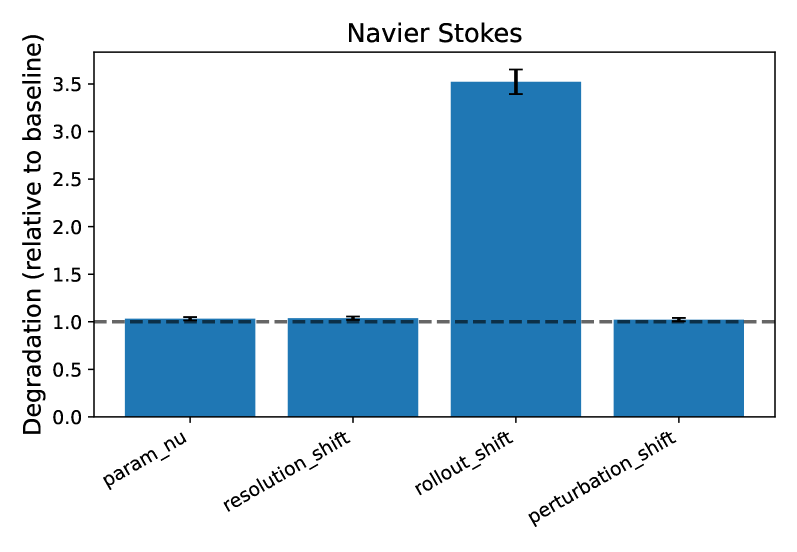

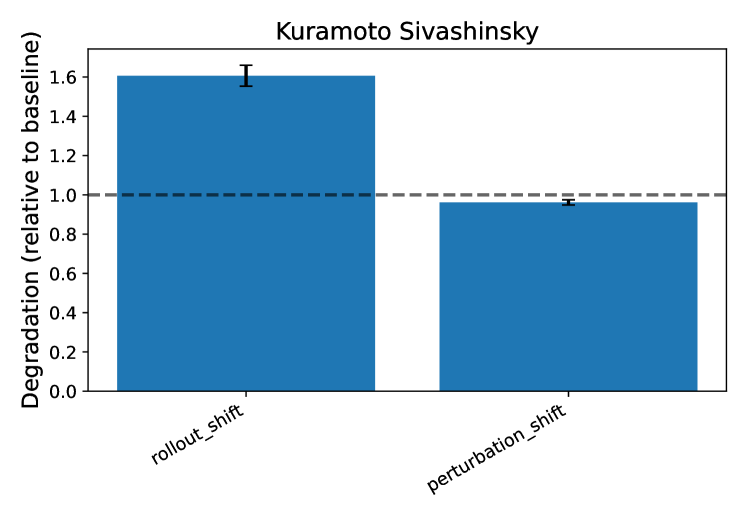

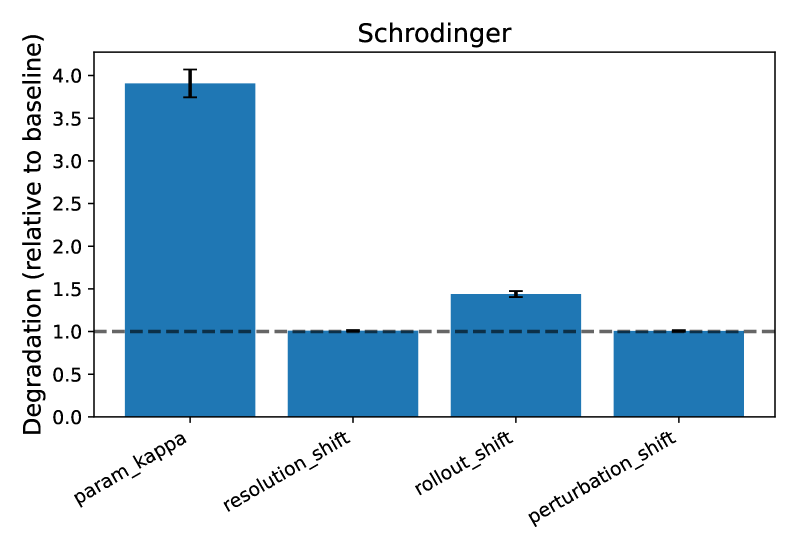

Long-horizon rollout predictions were implemented to evaluate the temporal stability of Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) models across five distinct partial differential equation (PDE) families. Systematic testing revealed substantial performance degradation when extrapolating beyond the training distribution; several stress tests exhibited mean degradation factors exceeding 1.5. This indicates a marked decrease in predictive accuracy as the prediction horizon increases and conditions deviate from those seen during training, highlighting limitations in FNO’s ability to maintain solution fidelity over extended time scales and under distributional shifts.

Unraveling Model Weaknesses: Error Propagation and Spectral Bias

Although Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) exhibit impressive generalization capabilities, simulations extending over longer time horizons reveal a critical vulnerability: the accumulation of integration errors. This phenomenon, inherent in the numerical methods employed within FNOs, causes even minor discrepancies at each step to compound over time, ultimately leading to instability and inaccurate predictions. The issue isn’t a failure of the model to learn the underlying physics, but rather a limitation in its ability to reliably propagate solutions over extended periods, particularly when dealing with complex or chaotic systems. This highlights a crucial consideration for deploying FNOs in real-world applications requiring long-term forecasting, where robust error mitigation strategies are essential to maintain predictive accuracy and prevent divergence from expected behavior.

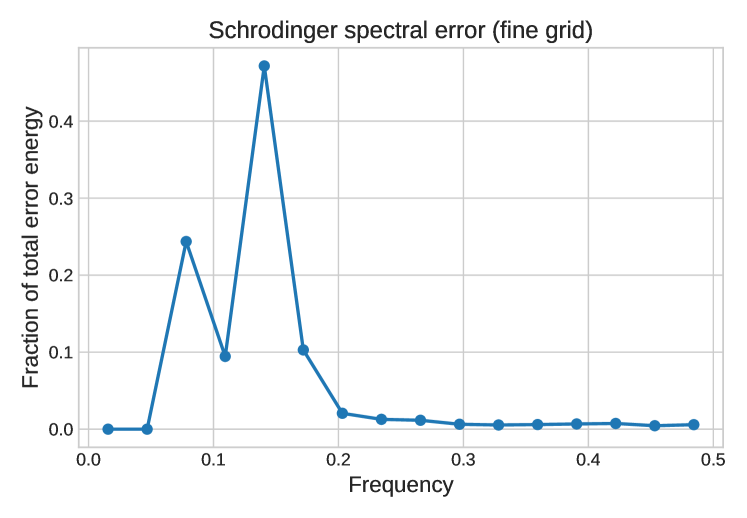

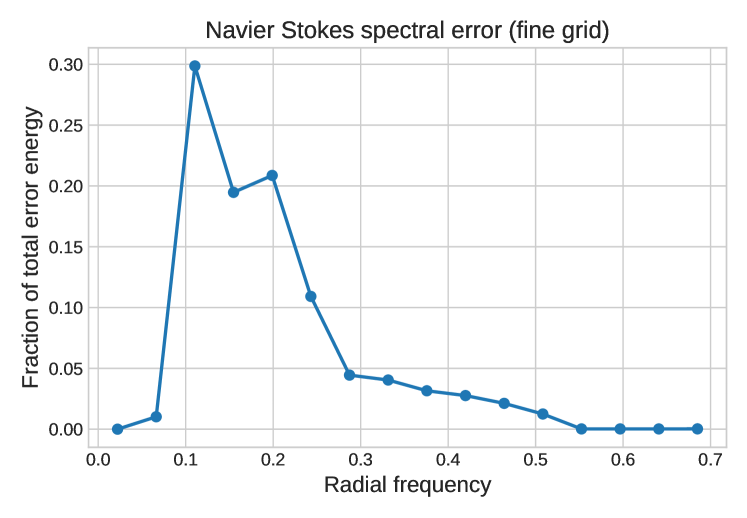

Like many neural network architectures, Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) exhibits a pronounced spectral bias, meaning it preferentially learns and represents lower-frequency functions while struggling with higher frequencies. This tendency stems from the inherent properties of the Fourier transform used within FNO, which efficiently captures global, smooth variations but requires more complex representations for rapid changes or fine details. Consequently, FNO excels at predicting large-scale patterns but can produce blurred or inaccurate results when dealing with high-frequency phenomena, such as sharp edges or intricate textures. Understanding this spectral bias is crucial for interpreting FNO’s outputs and developing strategies to mitigate its limitations, potentially through techniques like spectral normalization or the inclusion of high-frequency-aware loss functions.

A comprehensive evaluation of model robustness necessitates quantifiable metrics for error propagation, and the Error Degradation Factor, alongside Worst-Case Error analysis, provides precisely that. Investigations across diverse partial differential equations reveal significant performance degradation over extended prediction horizons. Specifically, the analysis demonstrated mean degradation factors of 1.97 for the Poisson equation – even with rough coefficients – and a more pronounced 3.9 for the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, indicative of challenges with stronger nonlinearities. Long-horizon rollouts of the Navier-Stokes equation exhibited a factor of 1.60, while financial modeling with the Black-Scholes equation showed particularly high sensitivity, with factors of 6.0 for discontinuous payoffs and 2.13 for volatility shifts. These values highlight the crucial need for targeted improvements to mitigate error accumulation and enhance the reliability of these models in practical applications.

Charting Future Directions: Towards Robust and Reliable PDE Solvers

Numerical solutions to partial differential equations (PDEs), particularly those evolving over time, are susceptible to the accumulation of errors with each integration step. This compounding effect can significantly degrade solution accuracy, even with sophisticated numerical schemes. Researchers are actively investigating strategies to mitigate this issue, prominently featuring adaptive time-stepping techniques which dynamically adjust the size of each time increment based on local error estimates – effectively concentrating computational effort where it’s most needed. Complementary approaches involve error correction mechanisms, such as predictor-corrector methods, where an initial estimate is refined using information from subsequent steps, or the application of post-processing filters designed to reduce the overall error magnitude. These advancements aim not simply to minimize local errors at each step, but to control the global error growth and achieve robust, reliable solutions over extended simulation times, proving critical for long-term predictions in fields like weather forecasting and fluid dynamics.

A significant challenge in applying neural networks to partial differential equations (PDEs) lies in their inherent spectral bias – a tendency to prioritize learning low-frequency functions while struggling with high-frequency details crucial for accurately representing complex physical phenomena. Researchers are actively investigating methods to overcome this limitation, including strategies to explicitly incorporate higher-frequency components during training. This involves augmenting training data with functions containing sharper gradients or employing specialized network architectures designed to better capture these features. Another avenue explores alternative spectral representations, moving beyond traditional Fourier-based approaches to representations that more effectively encode high-frequency information or offer improved numerical stability. Successfully mitigating spectral bias promises to unlock the full potential of neural PDE solvers, enabling their application to a wider range of scientific and engineering problems requiring precise modeling of intricate behaviors.

A comprehensive evaluation of Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) performance necessitates direct comparison with alternative operator learning architectures, notably DeepONet. Such analyses reveal critical architectural trade-offs – FNO’s efficiency in handling periodic data versus DeepONet’s flexibility with more complex, aperiodic functions – informing best practices for specific applications. Investigations into computational cost, memory requirements, and generalization capabilities highlight how each architecture scales with problem complexity and data availability. Ultimately, discerning these nuances guides the selection of the most appropriate operator learning framework for solving partial differential equations, pushing the boundaries of scientific machine learning and ensuring robust, reliable solutions.

The pursuit of universally robust neural operators, as detailed in this work, echoes a sentiment shared by many a mathematician. Carl Friedrich Gauss famously stated, “Few things are more deceptive than a simple appearance.” This rings true when considering the observed failure modes-spectral bias and compounding errors-within these ostensibly elegant architectures. The paper demonstrates that even seemingly successful models can exhibit fragility when subjected to distributional shifts. If the system looks clever-achieving high accuracy on standard benchmarks-it’s probably fragile, masking underlying weaknesses exposed by rigorous stress testing. The authors’ methodical approach to diagnosing these failures underscores the importance of understanding the whole system, rather than merely optimizing individual components; structure dictates behavior, and a flawed structure will inevitably manifest in predictable failures.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The systematic forcing of neural operators presented in this work reveals a disquieting truth: achieving apparent success on benchmark problems does not equate to genuine robustness. The observed failure modes – spectral bias, compounding errors – are not simply quirks of implementation, but rather symptoms of a deeper issue. The field has, perhaps, been optimizing for a readily achievable, but ultimately superficial, form of solution. What constitutes a ‘good’ solution to a partial differential equation? Is it merely numerical proximity to a reference solution, or does it demand a faithful representation of the underlying physics, even in regimes not explicitly represented in the training data?

Future work must move beyond the pursuit of ever-more-complex architectures. Simplicity, not as an aesthetic choice, but as a principle of clarity, should guide development. The emphasis should shift towards understanding the inductive biases inherent in these operators – what assumptions are baked in, and how do those assumptions limit generalization? Stress-testing, as demonstrated, is crucial, but it needs to be coupled with a more fundamental investigation of the solution landscape itself.

Ultimately, the goal is not to build a ‘black box’ that mimics solutions, but to create a system that embodies the essential principles of the underlying phenomena. This requires a willingness to confront the limitations of current approaches and to embrace a more holistic view of the problem – one where structure dictates behavior, and where the pursuit of elegance is not a luxury, but a necessity.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11428.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- Every Death In The Night Agent Season 3 Explained

- Gold Rate Forecast

2026-01-19 22:58