Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research uses computer simulations to explore how rapidly panic can spread among depositors and trigger a bank run, fueled by online communication and correlated behavior.

An agent-based model incorporating large language model-driven depositors and communication networks reveals the amplifying effects of social correlation on financial contagion and stress testing.

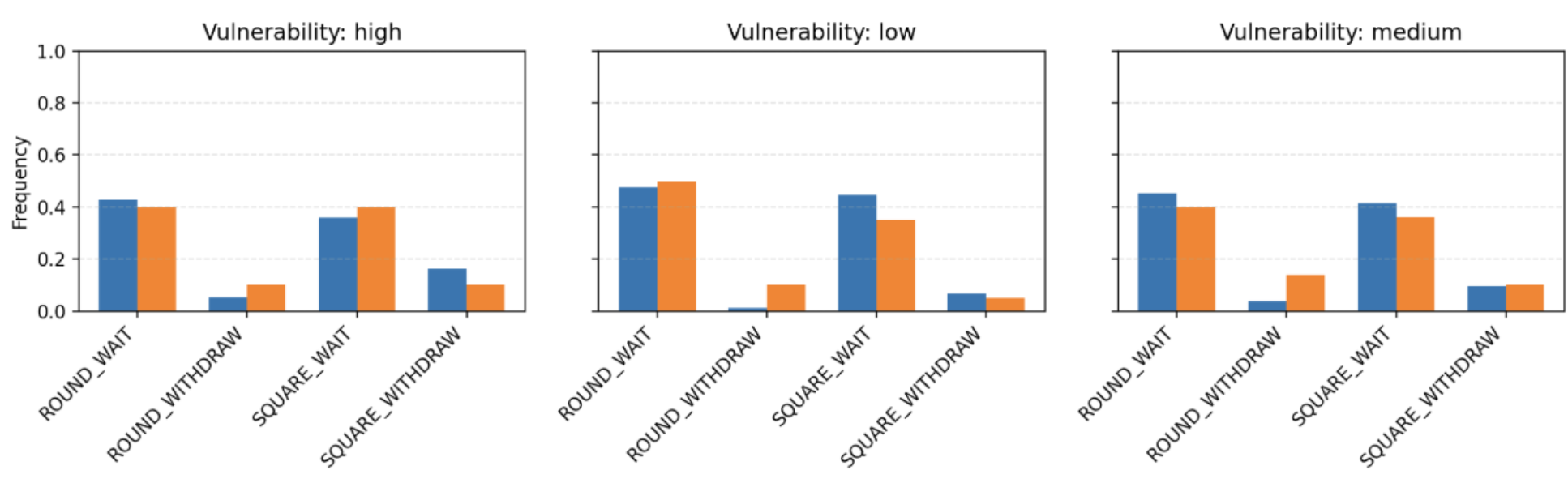

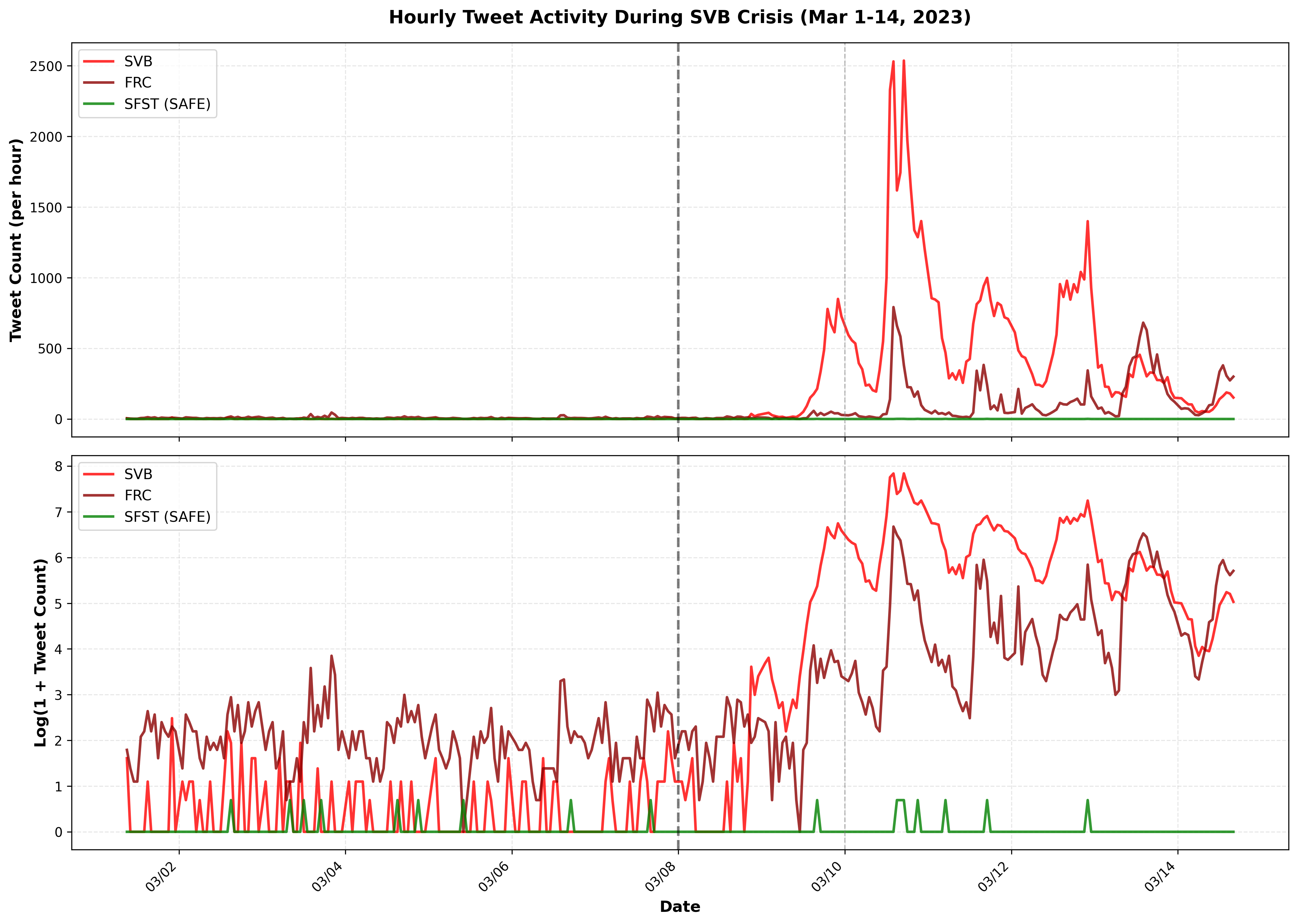

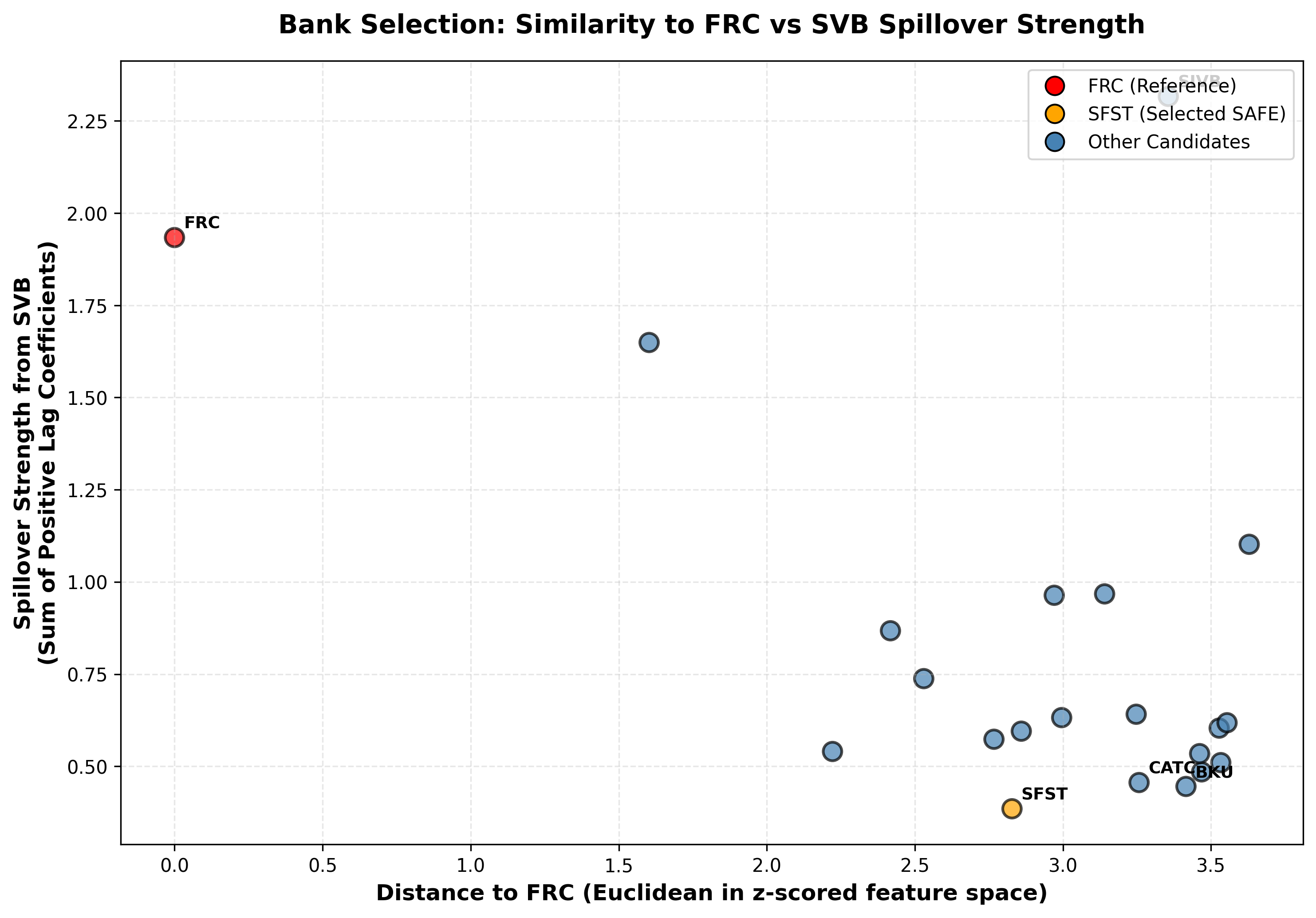

While equilibrium models capture the systemic risk inherent in bank runs, they struggle to explain the rapid synchronization of beliefs observed in modern, digitally-connected financial systems. This paper, ‘Social Contagion and Bank Runs: An Agent-Based Model with LLM Depositors’, addresses this gap by developing a process-based agent-based model where depositor behavior is driven by large language models operating on a communication network calibrated to real-world Twitter activity. Our simulations reveal that social correlation-amplified by network effects and within-bank connectivity-acts as a measurable driver of run risk, complementing traditional balance-sheet fundamentals. Can a more nuanced understanding of these digital contagion dynamics inform proactive stress-testing and ultimately enhance financial stability?

The Illusion of Rational Markets

Conventional economic frameworks, such as Equilibrium Theory, frequently posit that individuals make decisions based on logical calculations and complete information; however, this assumption falters when examining the phenomenon of bank runs. These models struggle to account for the powerful role of behavioral factors-like fear, herd mentality, and the rapid spread of misinformation-that override rational assessment during times of financial uncertainty. A bank run isn’t simply a collective, logical withdrawal based on objective financial indicators; it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy driven by a loss of confidence, where the expectation of insolvency-even if unfounded-becomes the very cause of it. Consequently, these models often underestimate the potential for rapid destabilization, failing to predict the speed and scale at which depositors may attempt to withdraw their funds, even from fundamentally sound institutions.

Conventional economic forecasting often struggles to predict the swiftness with which depositor anxiety can escalate into full-blown bank runs. Current models typically assess risk based on fundamental indicators – loan performance, asset quality, and capital reserves – but frequently underestimate the power of behavioral factors. Even relatively small negative news, or a perceived vulnerability at a single institution, can rapidly erode confidence. This isn’t a measured response to changing fundamentals; instead, it’s driven by a fear of being last in line to withdraw funds. The resulting rush to exit isn’t linear; it’s exponential, as each withdrawal reinforces the anxiety of others, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy where a solvent bank can fail simply because depositors believe it will. This highlights a critical gap in risk assessment – the need to account for the speed and intensity of psychological contagion within the banking system.

The stability of a bank isn’t solely determined by its assets, but critically by the web of relationships among its depositors. Depositors aren’t isolated entities making independent decisions; rather, they observe each other, share information-and anxieties-through social networks and media. This interconnectedness means a loss of confidence isn’t a gradual erosion, but can spread virally, transforming a localized concern into a widespread panic. Even fundamentally sound banks become vulnerable when depositors, witnessing others withdraw funds, preemptively follow suit, fearing they will be last in line. This herding behavior amplifies even minor initial shocks, creating a positive feedback loop that overwhelms traditional risk assessments and quickly escalates into systemic risk, potentially destabilizing the entire financial system. The speed and scale of these interconnected failures demonstrate that a bank’s fate is less about its internal health and more about the collective psychology of those who entrust it with their capital.

Simulating the Herd: Agent-Based Modeling Takes Center Stage

Agent-based models (ABMs) represent a computational approach to simulating complex systems by modeling the actions of autonomous, individual agents. In the context of bank simulations, each depositor is instantiated as an agent possessing specific attributes – such as account balance, risk aversion, and information access – which influence their individual decision-making processes regarding deposits and withdrawals. These agents operate based on defined rules and respond to internal states and external stimuli, including information received from other agents or events within the simulated banking system. Unlike aggregate models that rely on average behaviors, ABMs capture heterogeneity and emergent phenomena arising from the interactions of these individual agents, providing a more granular and potentially realistic representation of depositor behavior.

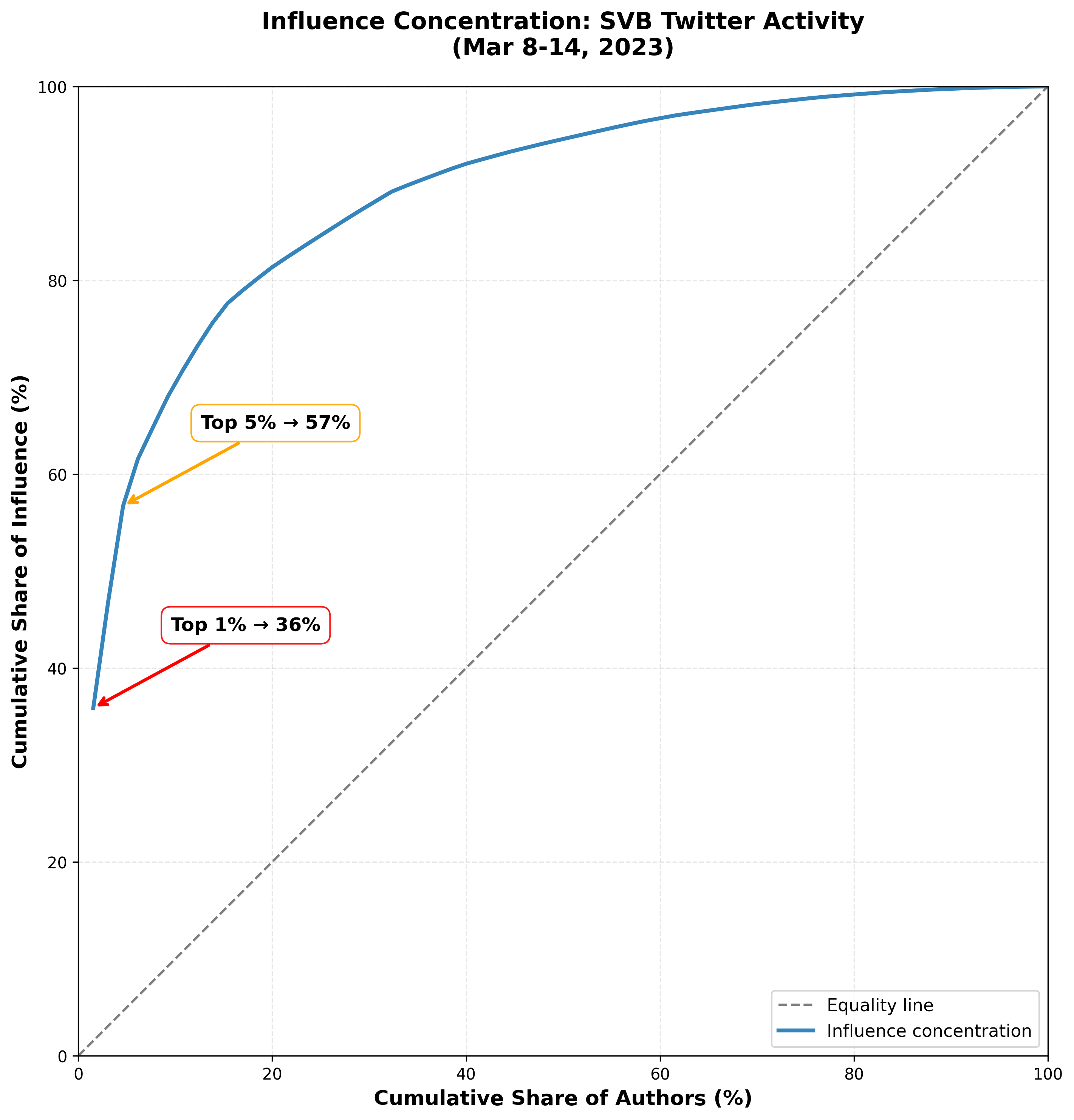

Agent-based models incorporate social network effects by representing depositors as nodes connected through relationships that define information flow. These connections are not necessarily complete; they can represent varying degrees of trust, frequency of communication, or shared affiliations. During simulations, information – including rumors of bank instability – propagates along these network links. The speed and extent of this propagation are determined by network topology – such as the presence of highly connected individuals (influencers) or clustered communities – and individual agent characteristics like susceptibility to rumor and the weight given to information from different sources. This allows researchers to analyze how network structure impacts the speed and scale of panic, and ultimately, bank stability, going beyond assumptions of uniform information dissemination.

Agent-based modeling enables the evaluation of bank resilience by subjecting simulated institutions to a range of predefined stress tests, including sudden economic downturns, negative news events, and fluctuations in depositor confidence. Unlike static analyses which provide a single point estimate of risk based on current conditions, these simulations allow researchers to observe the dynamic response of the bank and its depositors over time. Scenarios can be varied to assess the impact of different intervention strategies, such as deposit insurance levels or capital requirements. The resulting data provides insights into potential failure points and the effectiveness of mitigation tactics under conditions that are difficult or impossible to replicate with historical data or purely mathematical models. This capability is crucial for proactive risk management and regulatory oversight.

Decoding the Panic: Advanced Methods for Understanding Depositor Behavior

Agent-Based Models (ABMs) traditionally simulate depositor behavior using pre-defined rules; however, recent advancements integrate Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate more nuanced and realistic responses. LLMs are trained on extensive datasets of text and communication, allowing them to mimic human decision-making processes when exposed to various stimuli within the ABM. This approach moves beyond simplistic, rule-based reactions to incorporate contextual understanding and variable responses, improving the fidelity of simulated depositor psychology. Specifically, LLMs enable the simulation of how depositors interpret and react to information – such as news articles or social media posts – influencing their propensity to withdraw funds. The result is a more accurate representation of collective behavior and a more robust platform for analyzing systemic risk.

Agent-Based Models incorporating Large Language Models are capable of forecasting the impact of external stimuli on individual depositor behavior, specifically the propensity to initiate withdrawals. These models assess factors such as negative news reports, the spread of rumors regarding bank solvency, or even simulated social media posts, and translate those inputs into quantifiable changes in withdrawal probabilities for each simulated agent. The models determine likelihood based on an individual agent’s pre-defined risk aversion, financial situation, and perceived credibility of the information source, allowing for the simulation of diverse depositor responses to the same triggering event. This predictive capability extends to quantifying how varying intensities or frequencies of these external factors alter the overall rate of withdrawal requests within the simulated banking system.

Simulations utilizing Large Language Models demonstrate a substantial acceleration of bank run speed due to social correlation – the degree to which individuals are influenced by the actions of their peers. Specifically, modeling of the First Republic Bank scenario indicated an 85% probability of failure when social correlation was factored into the simulation. This suggests that the spread of information and subsequent withdrawal decisions are heavily influenced by observing the behavior of other depositors, significantly increasing systemic risk beyond that predicted by individual financial assessments or isolated events.

Simulations utilizing Large Language Models demonstrate that the combined influence of social correlation and network effects significantly amplifies bank run risk beyond the sum of their individual contributions. Specifically, the models show that the interaction between depositors observing peer withdrawal decisions (social correlation) within a connected network accelerates the speed and increases the probability of a bank run. Analysis indicates the synergistic effect is not merely additive; the impact of a given level of social correlation is substantially magnified when operating within a network structure, leading to a disproportionately higher risk of bank failure compared to scenarios where either factor is considered in isolation. This suggests that interventions aimed at mitigating run risk must address both individual depositor psychology and the systemic influence of social networks.

Beyond Prediction: Towards Truly Resilient Financial Systems

Sophisticated computational models are now capable of realistically simulating the complex dynamics of bank runs, offering a proactive approach to financial stability. These aren’t simply theoretical exercises; they directly inform and enhance stress testing procedures utilized by regulatory bodies and financial institutions. By subjecting virtual banking systems to a range of simulated shocks – from moderate economic downturns to sudden loss of confidence – these models identify hidden vulnerabilities and potential failure points before they materialize in the real world. This allows for the targeted strengthening of capital reserves, refinement of liquidity management strategies, and the implementation of preventative measures designed to absorb shocks and maintain systemic resilience. The ability to anticipate and address these weaknesses is crucial, moving the financial sector beyond reactive crisis management towards a more robust and preventative framework.

Financial simulations increasingly demonstrate that systemic risk isn’t solely driven by individual bank vulnerabilities, but by how information – and misinformation – spreads through the network. These models reveal a potent effect known as social correlation, where the actions of depositors are heavily influenced by observing the behavior of others; a perceived threat at one institution can rapidly trigger similar responses elsewhere, even if those institutions are fundamentally sound. This creates a cascading effect, amplifying initial shocks and accelerating the potential for widespread bank runs. Consequently, managing information flow – through transparent communication, proactive clarification of rumors, and strategic dissemination of positive signals – becomes as crucial as traditional risk management practices. Mitigating social correlation requires not just strengthening individual institutions, but fostering a more resilient and informed public, capable of discerning credible information from panic-inducing speculation.

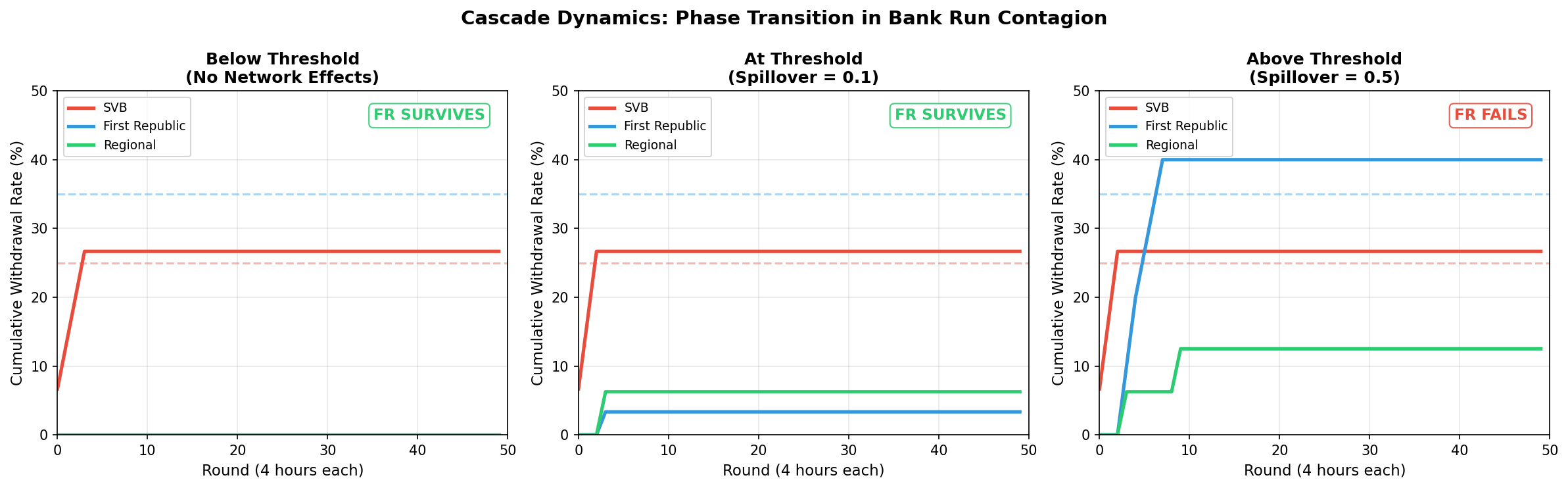

Recent research demonstrates that financial contagion doesn’t increase linearly, but rather experiences a critical threshold. Simulations reveal a distinct phase transition in systemic risk occurring when the spillover rate – the proportion of withdrawing depositors moving from one bank to another – reaches 0.10. Below this rate, the system exhibits relative stability; however, exceeding it triggers a cascade effect, dramatically increasing the probability of multiple bank failures. This suggests that even small increases in depositor movement beyond this critical point can destabilize the entire financial network, transforming localized concerns into systemic crises. Understanding this phase transition is crucial for regulators, enabling them to proactively implement safeguards and prevent the rapid escalation of risk before it overwhelms the system.

When faced with a surge in withdrawal requests exceeding available liquid assets, a bank may be compelled to initiate a fire sale of its holdings. This forced liquidation – selling assets rapidly at depressed prices – can trigger a cascading effect throughout the financial system, as diminished asset values impact other institutions. Such scenarios demonstrate the critical importance of proactive risk management, including maintaining sufficient liquidity buffers and diversifying asset portfolios. Failing to prepare for extreme demand can not only threaten the solvency of an individual bank, but also contribute to systemic instability, highlighting the need for robust regulatory oversight and comprehensive stress-testing procedures to prevent widespread financial crises.

The simulations detailed in this work predictably demonstrate how easily rational actors, when linked through communication networks, devolve into panicked herds. It’s a familiar pattern; the model merely formalizes what seasoned observers have always known. As Grigori Perelman once observed, “It is better to be slightly paranoid than to be completely trusting.” This sentiment resonates with the agent-based model’s findings – a small degree of ‘paranoia’ (represented by heightened sensitivity to negative information or correlated behavior) can rapidly escalate into systemic risk. The study highlights social correlation as a key amplifier of stress, and it’s comforting to see a mathematical model validate the suspicion that scalable systems often haven’t been tested against the irrationality of connected individuals.

What Comes Next?

The simulation reliably demonstrates what production already knew: panic is more efficient than reason. The incorporation of LLM-driven agents, while novel, simply refines the observation that correlated behavior-regardless of its underlying mechanism-amplifies systemic risk. The model’s calibration against historical data offers a temporary illusion of predictive power; every stress test is, at best, a well-informed guess about the next novel failure mode. The true cost of this work isn’t computational cycles, but the accruing technical debt of increasingly complex simulations.

Future iterations will inevitably pursue greater realism-more granular agent characteristics, more sophisticated communication topologies, perhaps even attempts to model the evolution of trust. But a more pressing question concerns validation. Can these models, even with perfect data, distinguish between a genuine liquidity crisis and a coordinated attack? Or will they simply confirm existing biases, labeling every tremor as a full-blown run? Tests are, after all, a form of faith, not certainty.

The ultimate utility may not lie in prediction, but in the articulation of failure modes. Perhaps the most valuable output is not a warning of when a run will occur, but a detailed catalog of how it might unfold, and the absurd, cascading errors that inevitably accompany it. The system will always find a way.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15066.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- United Airlines can now kick passengers off flights and ban them for not using headphones

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- How To Find All Jade Gate Pass Cat Play Locations In Where Winds Meet

- How to Complete Bloom of Tranquility Challenge in Infinity Nikki

- Every Battlefield game ranked from worst to best, including Battlefield 6

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 29 Years Later, A New Pokémon Revival Is Officially Revealed

- Best Zombie Movies (October 2025)

- Pacific Drive’s Delorean Mod: A Time-Traveling Adventure Awaits!

- How School Spirits Season 3 Ending Twist Will Impact Season 4 Addressed By Creators

2026-02-18 08:24