As someone who grew up in the late 80s and early 90s, I can vividly remember the cultural phenomenon that was Bart Simpson. His antics and the “underachiever” shirt were indeed shocking and provocative at the time, but they represented a refreshing departure from the more innocent days of Dennis the Menace. Bart symbolized a new era of television that pushed boundaries and wasn’t afraid to be edgy.

In 1990, Matt Groening found “HOME OF BART” spray-painted on his two-bedroom cottage in Venice, California. His initial thought was, “How do they know I live here?” But then he realized, “They didn’t.” This showed how much his new show had gained popularity, as even his house could potentially be recognized and targeted randomly.

Speaking with a touch of humor from his office in Santa Monica, the creator of “The Simpsons” remarks, “At least,” I prefer to believe, was purely a coincidence.

In a surprising or unintentional way, the words were undeniably reminiscent of Matt Groening’s character, Bart Simpson, known for his sassy retorts, mischief, pranks, and graffiti art. Exactly 35 years ago today, we were introduced to Bart in the Christmas special “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire.” He was caught mocking “Jingle bells, Batman smells” during his school’s Christmas performance and lying about his age to get a tattoo. However, the real surprise of the episode and a foreshadowing of things to come, is when Bart greets Santa in a department store with what would become his iconic catchphrase: “I’m Bart Simpson. Who are you?” This phrase quickly echoed around the globe.

Prior to Bart’s television debut, there had never been a character quite like him. He stood out in cartoons, prime-time dramas, and even family sitcoms. According to creator Matt Groening, he drew inspiration for Bart from his own childhood feelings of frustration in the classroom. This gave Bart an outlet for the mischievousness that Groening had mostly held back. As Mike Reiss, one of the show writers, put it, “We were all ‘Lisas who wanted to be Bart.’ We knew he would be our breakout character. Although we weren’t cool like him, we could all relate to his rebellious spirit.

The unexpected magnitude of the response that Reiss, Groening, and the team behind The Simpsons received was unforeseen. In just a few weeks of 1990, The Simpsons had become ubiquitous, gracing the covers of magazines like TV Guide, Entertainment Weekly, Newsweek, and Rolling Stone, which portrayed the family as if they were real individuals. They could also be found on shows such as Entertainment Tonight and The Larry King Show, and their distinctive yellow color, designed for maximum visibility, adorned an assortment of merchandise ranging from bean bags to beach towels, T-shirts to talking toothbrushes, yo-yos to yarmulkes.

As a devoted movie-goer, I can’t help but notice the unavoidable presence of the Simpson dynasty. From floating above NYC parades to serenading on MTV and endorsing Butterfingers, it was hard to miss Bart Simpson. In fact, at one Orlando high school, Bart even ran for class president, making headlines when a 24-year-old Bexar County businessman named Bart Simpson expressed interest in running for the District 115 House seat (“I do have a name that people would recognize,” he said). And to top it all off, at the Emmys, Bart consistently stole the limelight, even landing an Outstanding Lead Actor nomination for “Bart Simpson on The Bart Simpson Show!

In those days, it almost felt like “The Bart Simpson Show” had come to dominate contemporary life. As a representative from Amurol Products, who launched three Bart Simpson-themed bubble gums that year, aptly summarized: “Bart mania is sweeping across the nation.

Bart was a topic of national interest, sparking debates in broader societal discussions about shifting family structures, educational values, and the transforming world of television. For numerous individuals, the Bartmania craze represented a vivid display of social unease, with the character symbolizing moral decline and potential harm to society. About a decade before “The Sopranos,” several publications referred to Bart Simpson as an “anti-hero.

In 1990, executive producer Sam Simon expressed to the Los Angeles Times that he had never received such a large volume of angry letters. Recently, when I spoke with him, Reiss reminisced about a confrontation with an old acquaintance from his past. “He approached me and said, ‘How can you broadcast such rubbish on television? I have children to raise.’ That was a real wake-up call for me. I was quite embarrassed,” he shared.

Currently, Groening, who continues to serve as an executive producer on the show, discusses Bart and Bartmania with a touch of affection, much like a parent amused by their mischievous child’s actions. “For me,” he remarks with laughter, “the pinnacle accomplishment lies in having a significant portion of your audience find something offensive, while another group adores it.

***

In a bold move that showcased his early mischief, Bart – whose character was later created – showed up late to the Simpson family gathering. It wasn’t until 1987 that cartoonist Matt Groening sketched this rowdy family outside James L. Brooks’ office. He named them after his own relatives: Homer, Marge, Lisa, and Maggie. Initially, Bart was intended to be named after himself, but he decided against it as he thought it would come off as overly self-important. Instead, he chose a name that sounded more aggressive, reminiscent of a dog’s bark, which would later become the character we know as Bart.

Initially, Bart didn’t resemble his future self at all, with a vaguely defined cloud of hair. It wasn’t until Klasky Csupo animation studio was assigned the job and proposed to animate the cartoon in color that Groening recognized the need to define where Bart’s hair stopped. He created a more distinct silhouette, featuring a jagged sawtooth appearance reminiscent of Johnny Rotten or a hi-top fade. Later, when animation director David Silverman softened the serration, the character still retained an edgy demeanor. Nancy Cartwright, who initially intended to audition for Lisa’s role, was captivated by the description of Bart’s older brother: “devious, underachieving, school-hating, irreverent, clever.” (Later, during the development of the series and with her first pregnancy, Cartwright begged her unborn child not to become Bart.)

I find myself quite similar to Bart’s characterization. Much like many children, I found school tedious, which led me to express my boredom in unconventional ways. Growing up in Portland, Oregon, I constantly sought ways to avoid the monotony. On my very first day of first grade, I began secretly sketching in class. My drawing style, characterized by large eyes and a pronounced overbite, was developed from what I could create without looking at the page, all while attempting to appear focused. Needless to say, I was usually discovered, with teachers seizing or even tearing up my drawings.

In my perspective, the grown-up realm seemed drab and harsh, yet as I navigated through it, a sense of longing for the carefree days of childhood persistently lingered. “As a child,” I mused, “I vowed to forever remain a child at heart. My peers were destined to become career adults with briefcases. Yet, in my heart, I was certain that my fate was intertwined with creating humorous tales and sketching cartoons, regardless of the outcome.

Simultaneously, Groening held a complex affection for television, compulsively watching it while constantly desiring its improvement. He recalls being enthused by the live-action Dennis the Menace TV series, whose animated introduction portrayed Dennis as a chaotic whirlwind akin to the Tasmanian Devil in Looney Tunes. However, in his opinion, the character became weak instead. Groening longed for the day when the tornado wouldn’t subside.

***

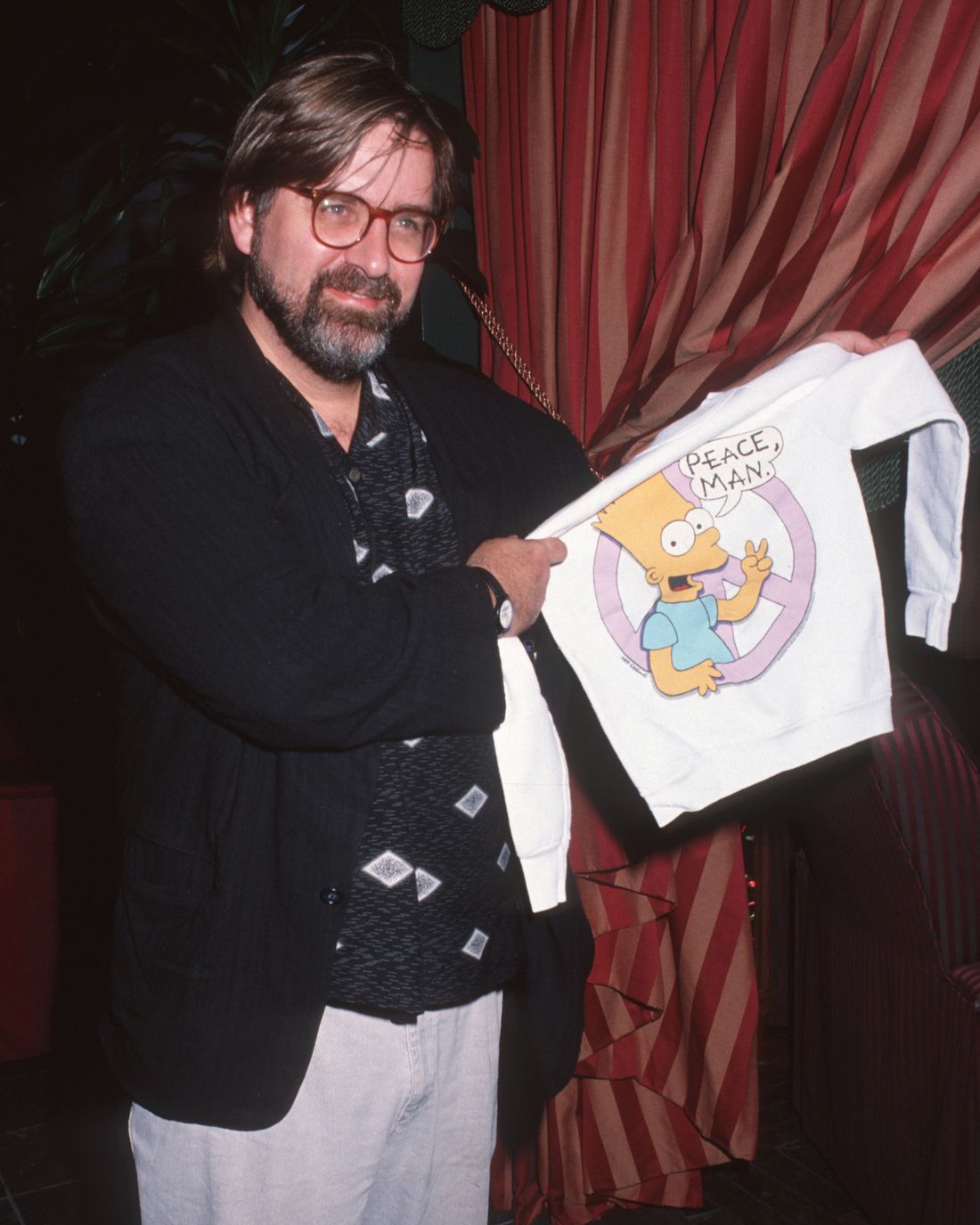

In the aftermath of a decade where cartoons were created primarily for marketing toys with a sarcastic edge, the commercial success of The Simpsons, driven by genuine audience enthusiasm, was as widespread and impactful as a biblical plague. By 1990, the show generated an astonishing $750 million through merchandise and other sales. During the peak of Bartmania, up to a million Bart Simpson t-shirts were selling every day. A representative from JCPenney stated, “As soon as it arrives, it sells out immediately” to the New York Times.

In the initial year of the show, Groening was thrilled by the unexpected surge of Simpsons-related items that flooded in from aspiring licensees, numbering over a hundred per day. As Craig Bartlett, Lisa Groening’s husband and creator of the animated series “Hey Arnold!”, recounted, “Groening was ecstatic when playing the Simpsons pinball machine.” In fact, Groening adorned an entire guest room in his house with Simpsons merchandise, happily commenting that guests would usually only stay for a single night.

As the popularity of The Simpsons skyrocketed, I too saw an enticing and profitable chance. Merchandise featuring Bart Simpson began popping up everywhere just weeks after the show’s debut. On sidewalk stalls across the nation, you could find shirts like “Teenage Mutant Ninja Simpson,” “Air Simpson,” “Rasta Bart,” and many others. Each shirt seemed to embody a different aspect of Bart’s character, from his rebellious spirit to his skater style. Some even reflected the growing trend of “Afro-Americanizing” Bart, as described by one reporter, with shirts like “Bart Simpson Public Enemy” and “Gangsta Bart.” As Bill Stephney, a record-label president, put it, Bart might just be “more rebellious than a lot of the rappers today.

Despite owning a large portion of the merchandise, Groening remained amused by Bartlett’s account of his reaction to the growing copycat market, as expressed by Groening’s creator, Matt Groening. Groening took Bartlett to the Venice boardwalk to buy “Simpsons go kinky reggae” T-shirts that cost five dollars each. The television reviewers’ approval pleased Groening, but it was particularly gratifying for him that Bart identified with these resourceful counterfeiters. As Bartlett put it, Groening was on the lookout for a unique crossover T-shirt featuring Nelson Mandela and Bart Simpson. Remarkably, such a shirt was found later that year.

Despite being controversial, the Bart-themed shirt, which portrayed Bart preparing to shoot a slingshot while sporting the label “Underachiever” and the phrase “and proud of it, man,” was actually an officially licensed product. In April 1990, Principal Bill Krumnow of Lutz Elementary School in Ballville Township, Ohio, prohibited students from wearing this particular Bart shirt due to its content.

Rapidly, the “underachiever” shirt found itself at the epicenter of the uproar surrounding the show, fueled by the media. As a result, more schools across the nation enforced bans on the shirt, and JCPenney decided to discontinue selling it in children’s sizes. Krumnow explained his stance to the Toledo Blade, stating, “It’s contradictory to our values to be proud of being incompetent.” Lonnie Watts, principal of Taylor Mill Elementary School, echoed this sentiment, saying, “The Bart Simpson show promotes behaviors that do not enhance student self-esteem, including the idea that it’s acceptable to be unintelligent.

Amidst others feeling discomfort, Groening found delight in stirring controversy. “It’s amusing to challenge authority, and indeed, the ban of those t-shirts in schools had me chuckling.

As a movie enthusiast, I’d rephrase it like this: To Matt Groening, the motto “was all about education.” Bart Simpson wasn’t someone who saw himself as an underachiever. Instead, he was taking a stand against the educational system that so casually labeled children with such a term. “I might have been labeled an underachiever myself,” muses Groening. “And my response? I wear it as a badge of honor.

****

Following the broadcasting of reruns for “The Simpsons” after its season one finale in May 1990, criticism and discussions regarding the show escalated. Barbara Bush labeled it as “the most idiotic thing I’ve ever seen.” Two nuns even created T-shirts with depictions of saints, hoping that Bart would be counterbalanced. William Bennett, a former secretary of Education who later became the drug czar, voiced his disapproval upon seeing a Bart Simpson poster at a drug rehabilitation center: “Aren’t you watching ‘The Simpsons’? That won’t assist your recovery in any way.

The conflict arose when Fox disclosed that in its second season, “The Simpsons” would shift from 8 p.m. ET on Sunday evenings to the same slot on Thursday nights, placing it against “The Cosby Show,” which consistently led in ratings on NBC. This event was portrayed by the media as a clash between Bart and Bill, a confrontation between one show’s traditional family values and the other’s rebellious, sarcastic nature — the idealistic 1980s versus the rebellious 1990s. When prompted for comment, Cosby stated that television should be progressing towards the Huxtables, not backwards. He criticized shows with a negative attitude, claiming they believe this kind of programming is “the edge,” but argued that we shouldn’t find entertainment in such behavior.

As a film enthusiast, I wouldn’t have been surprised if “The Simpsons,” in its October 1990 season-two premiere, had gone all out with its humor, pushing even further into edginess. But what viewers got instead was something truly heartwarming and impactful. In the episode titled “Bart Gets an F,” Bart finds himself facing the possibility of repeating the fourth grade. He puts in a lot of effort studying, sincerely prays for a miracle (which unexpectedly occurs), and crumbles, defeated, when he fails again.

At one of the most touching scenes in the series yet, Bart finds himself dozing off between the pages of a school book, after putting in considerable effort but ultimately failing at a last-minute study session. Marge ponders, “Why does he work so hard and still fall short?” Homer, showing genuine care, lifts his son up and carries him to bed, saying, “I guess he’s just not the brightest.” In essence, he’s struggling academically but trying his best.

Despite the episode subtly referencing the T-shirt debate (“Bart is an underachiever,” a child psychologist tells Homer and Marge, to which they respond, “And yet he seems to be… proud of it”), it wasn’t a response to the controversy or a deliberate attempt to improve Bart’s image. As stated by animation director David Silverman on the episode’s DVD commentary, it was simply an idea that seemed fitting for an episode. Showrunner Al Jean echoed this sentiment: “We never do anything with a specific reason in mind.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=watch?v=_eItvYvBVe8

Despite being known as an unapologetic hellion during season one, viewers got a glimpse of a gentler, kinder side of Bart in “Bart Gets an F.” This episode, which was seen by 33.6 million people according to Nielsen Media Research, remains the most watched episode of the show to date. In fact, Entertainment Weekly named Bart their “Entertainer of the Year” for 1990, praising the character’s transformation into a rebel with a heart, a troublemaker who could also be easily scared, and a carefree individual capable of surprising displays of bravery.

Despite this, some individuals might continue to express being upset or feign offense. For instance, Nancy Cartwright recalled a conversation where three mothers were discussing a new series named “The Simpsons” that they intended to keep their children away from. “I intervened,” she said, “expressing my understanding of their right to their opinions. I also inquired if they had ever watched the entire show. It turned out none of them had.

In the course of the ’90s, the more authentic, complex portrayal of family life in “The Simpsons” resonated more deeply than “The Cosby Show.” Even Bill Cosby, years later, expressed a tender affection for Bart, suggesting that his academic struggles were rooted in a learning disability. Matt Groening, the creator, attributes the show’s enduring popularity to its ability to depict the simultaneous chaos and genuine familial bonds, as exemplified in the episode “Bart Gets an F.” According to him, this portrayal of coping with people you care for deeply but who also drive you up the wall is something many can identify with.

***

For a period, Bartmania continued to thrive. In 1991, “Do the Bartman” remained on the Billboard’s “Hot 100 Airplay” chart for 11 weeks, and during this time, four games centered around Bart were released. Additionally, Fox halted the sale of unauthorized “Nazi Bart” merchandise. Soon, comic books titled “Bartman” and “Bart Simpson’s Guide to Life” began to be sold in backpacks bearing Bart Simpson’s image. In 1993, the term “Bart Simpson” was synonymous with mischief: a human-relations expert in White Plains, New York, reported an increase in “irrelevant, confrontational, rebellious” behavior among high school students, labeling it as the “Bart Simpson syndrome.

However, it was later discovered that the focus of the show had transitioned from Bart to Homer. As explained by Reiss, “During seasons one and two, we exhausted all the story ideas we could come up with for Bart. Essentially, he’s just a 10-year-old boy and his life isn’t as complex or rich as Homer’s.

As a dedicated film enthusiast, I’ll let you in on a little secret: Homer’s blunders carry much heavier consequences than Bart’s academic struggles. For instance, Homer accidentally causing a nuclear meltdown at work is far more impactful than Bart flunking a class. Groening himself acknowledges this.

During one of his yearly trips to the L.A. County Fair, Reiss noticed that Bartmania was gradually fading. “For about two years straight, any carnival game’s grand prize was a stuffed Bart Simpson doll,” he explained. “However, around the third or fourth year of the exhibition, I suddenly observed that wasn’t the preferred prize anymore. A few years later, I found myself thinking, ‘Wow, it’s Stewie and Brian from Family Guy‘ instead.

By 1994, “The Simpsons” had moved beyond its initial family-centric comedy roots and delved deeper into its eccentric cartoon nature. In essence, the episode “Bart Gets an F” transformed into “Bart Gets an Elephant.” Bart’s antics became less relatable as a role model for children due to the show’s increasing detachment from real-world circumstances.

Over time, Fox executives dreamt about recreating the Bartmania craze by introducing a character even more like Bart. In response, The Simpsons creatively poked fun at this idea by introducing a sunglasses-donning dog named Poochie to The Itchy & Scratchy Show. As Groening explains, it was a satirical take on the practice of adding new characters late in a sitcom’s run to boost ratings. The episode was one of their best, but ironically, people still express fondness for Poochie and ask for him to return!

But there was no bringing back Bartmania. The show had already paved the way for other shows to push the boundaries of what was acceptable ever further, not just in animation (Beavis and Butt-head, South Park, Family Guy) but all over television: the shallow, self-centered protagonists of Seinfeld, the freak-show spectacle of The Jerry Springer Show, the skewering cynicism of The Daily Show. In a few short years, Bart’s antics felt as essentially innocent as those of Dennis the Menace had to Groening in the ’60s.

According to Groening, the culture has become significantly rougher. Reiss concurs, reminiscing fondly about a time that was more innocent, and admits, with a hint of contentment, “Indeed, we contributed to that shift in culture towards roughness.

Currently, a T-shirt depicting Bart Simpson as an “underachiever,” once seen as a daring statement and symbol of societal decay around 1990, now holds a place of pride in the Smithsonian’s esteemed collection.

Read More

- FARTCOIN PREDICTION. FARTCOIN cryptocurrency

- SUI PREDICTION. SUI cryptocurrency

- Excitement Brews in the Last Epoch Community: What Players Are Looking Forward To

- The Renegades Who Made A Woman Under the Influence

- RIF PREDICTION. RIF cryptocurrency

- Smite 2: Should Crowd Control for Damage Dealers Be Reduced?

- Is This Promotional Stand from Suicide Squad Worth Keeping? Reddit Weighs In!

- Epic Showdown: Persona vs Capcom – Fan Art Brings the Characters to Life

- Persona Music Showdown: Mass Destruction vs. Take Over – The Great Debate!

- “Irritating” Pokemon TCG Pocket mechanic is turning players off the game

2024-12-17 21:55