In December, filmmaker Mira Nair was back in India getting ready to film Amri, a movie about the life of painter Amrita Sher-Gil, whom she compares to Frida Kahlo. She described the busy weeks of travel, from Amritsar near the Pakistan border to Kochi in the south, as both challenging and exciting, noting the film had been in development for four years and was finally starting production. This trip also marked her first time traveling internationally since her son, Zohran Mamdani, was elected mayor of New York in November. She was surprised and delighted to find that people recognized her not just for her films, but also because of her son. While visiting small towns and villages, she’d hear people excitedly calling out, ‘Mira Nair?!’ and then shouting their support for her son.

Less than a week before New Year’s Day, and just before Mahmood Mamdani was set to become New York City’s first Muslim mayor, we visited him and his wife, Nair, at their apartment in Morningside Heights. The apartment, owned by Columbia University where Mamdani has taught since 1999, overlooked a snowy Manhattan. It was filled with family who had recently arrived from India and East Africa, as well as books, photos, and art. Everyone had enjoyed bagels and lox from Zabar’s and was looking through hats, preparing for the frigid temperatures expected on Inauguration Day.

Mira Nair is arguably the most well-known Indian filmmaker working today. Her 1988 film, Salaam Bombay!, made history as the first Indian film to win the Golden Camera award at the Cannes Film Festival and was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Mississippi Masala (1991), featuring early performances by Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury, is a beautifully shot and critically praised film that thoughtfully explores themes of love and the challenges faced by those who feel displaced. Nair’s biggest mainstream success, Monsoon Wedding (2001), was a major hit in the U.S. and earned her the distinction of being the first Indian woman to win the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival.

It’s well-known that Zohran Mamdani comes from a privileged background. This was a frequent talking point during his surprising mayoral campaign, with many labeling him a product of wealth and connections. He’s often described as having gotten his progressive political views from his father, a Columbia professor and anti-colonialist thinker, and his charisma and showmanship from his filmmaker mother. However, the link between his mother’s artistic career and his path as a politician is deeper than just a shared creative flair.

Nair’s work is known for tackling difficult topics – like being exiled, troubled families, and discrimination – with a light touch, using humor, sensuality, vibrant imagery, and upbeat music. She prioritizes entertaining her audience, believing it’s her role to find moments of joy even when dealing with serious issues, famously saying, “It shouldn’t feel like homework!” This approach is also evident in her son’s mayoral campaign, which used creative elements like modern design, playful events, and diverse languages to make important issues like affordable living and inequality feel accessible and engaging, rather than preachy.

Mamdani’s approach to politics often reflects the artistic values instilled in him by his filmmaker mother. He explained to me earlier this year, “People sometimes underestimate the effort and thoughtfulness that go into art.” He recalled his mother emphasizing the need for both sensitivity and resilience, telling him, “You need the emotional depth of a poet, combined with the toughness of an elephant.”

She talked about what it takes to be a filmmaker, and her insights actually apply to politicians too. Those who know both of them point to their shared traits – huge goals and unwavering self-belief – as the reason they’ve both achieved so much in unexpected ways.

Bart Walker, Zohran’s agent for many years, explained that Zohran’s success is rooted in the groundbreaking work of Mira. Before Mira, there were no Indian female filmmakers whose work reached American audiences. She truly paved the way for others with her talent, personality, and determination – a story that echoes Zohran’s own journey, doesn’t it?

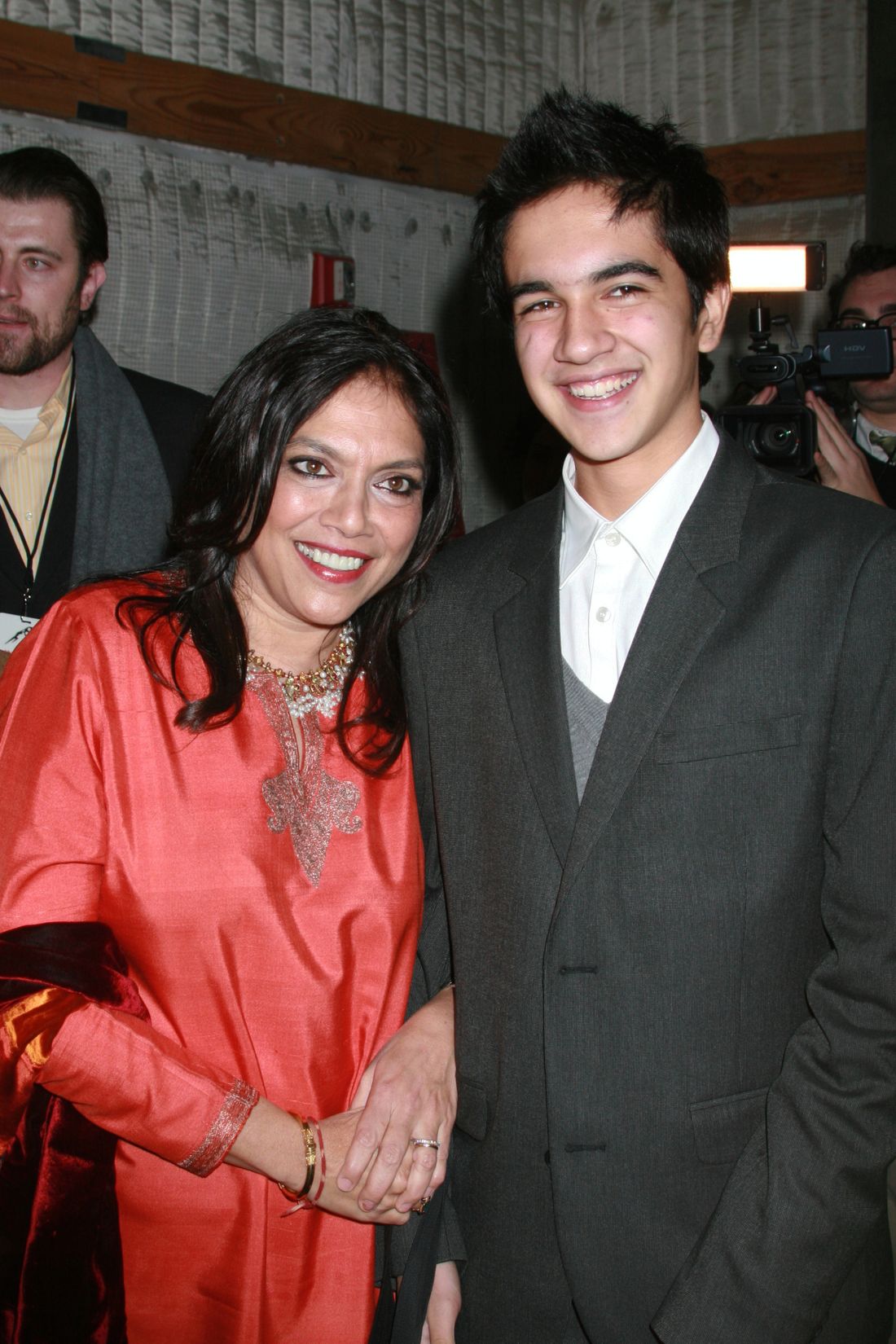

The way Walker’s description perfectly fits New York City’s mayor isn’t a coincidence. She playfully told journalist Mehdi Hasan at her son’s election party that she was “the producer of the candidate,” and at his inauguration, declared she would be “the mother of New York City.” These statements are affectionate, enthusiastic, and humorous—Nair’s own mother once joked to reporters she was “the producer of the director.” But they also shed light on how Mamdani became who he is, suggesting he’s as much a product of his mother’s influence as he is an artist.

I recently spoke with the mother of a fascinating and ambitious individual, and her insights into his upbringing were truly revealing. She essentially raised her son to believe anything was possible – even running for mayor of New York City, despite a lack of traditional qualifications. She did this not by accident, but through a deliberate strategy of unwavering support and a belief in exceeding expectations. As she explained it, she felt you only get one chance to raise a child, and she and her husband focused on ‘marinating’ him in love – creating a secure and protective environment that would give him strength and confidence throughout his life. It was a powerful testament to the impact a loving upbringing can have.

It’s easy to imagine a difficult upbringing leading someone to become self-centered, but so far, Mamdani seems like one of the most promising politicians of his generation. His mother, Nair, believes he’s remained grounded because of the strong support he receives, stating, “He really hasn’t changed, thanks to all this love and encouragement.”

Born in 1957 in Rourkela, India, to a comfortable middle-class family, Mira Nair grew up in the eastern state of Odisha. Her father, Amrit, was a prominent government official originally from Punjab, while she was closer to her mother, Praveen, who worked as a social worker. Her parents later separated in 1990. After studying at Delhi University for a year, Nair received a scholarship to attend Harvard University in 1976 and moved to the United States.

When Mira Nair was an undergraduate at Harvard, South Asian students were rare. One of them was Sooni Taraporevala, who became a close friend and frequent writing partner. Taraporevala remembers the 19-year-old Nair as strikingly bold, often wearing a dramatic winter coat like a cape, and incredibly determined. When the renowned Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray visited Boston, Nair and Taraporevala waited in a long line with friends to see him. But Nair, in a characteristic move, disappeared and managed to get inside. “She just slipped in and sat right near him,” Taraporevala said. Taraporevala’s grandmother, who had a fondness for spirited individuals, particularly adored Mira, affectionately calling her “Tohfaani avee”—Parsi Gujarati for “the Storm Has Arrived.”

Nair fell in love with Mitch Epstein, a teaching assistant in her photography class at Harvard. They spent the summer of 1978 together in New York City and then made the move permanent after Nair graduated in 1979. According to Taraporevala, Nair was energetic and always busy, constantly networking and meeting new people.

I always knew I wanted to be an actor, and that’s really what brought me here. Back in college, I even won Harvard’s Boylston Prize for performing a speech from Seneca’s Oedipus. When I moved to New York, I fell in love with the experimental theater happening downtown. I trained with Ellen Stewart at La MaMa and was completely inspired by artists like Joseph Chaikin, Andrei Serban, and Elizabeth Swados. In fact, Swados’ 1978 musical Runaways, which told the stories of homeless kids in New York, really stuck with me. It was a seed of an idea that eventually blossomed into my film, Salaam Bombay! ten years later.

Nair once worked as a server at the now-defunct Indian Oven on Columbus Avenue. She explained that this job gave her insight into the different situations of immigrants in the US. She described a hierarchy where undocumented workers, primarily Mexican, did the lowest-paying, most physically demanding work in the basement. Above them, Bangladeshi workers with temporary legal status cooked the food on the main floor. Finally, those with full legal status managed the restaurant and, she said, often mistreated the staff.

She and Epstein initially shared apartments on West 93rd Street and then West 19th, paying under $300 a month in rent. They often ate out for just $7 a meal at Empire Szechuan on 96th and Broadway. Nair recalls that the single-room occupancy buildings were all located on Riverside Drive, and people were warned to avoid walking there. Despite the hardship, she remembers it as a lively time in New York City. Epstein was mentored by Garry Winogrand, and they frequently socialized, while photographer Joel Meyerowitz lived close by.

After graduating, Nair found a daytime job at an African art gallery on Madison Avenue, but it rarely had any visitors. She used the quiet time, surrounded by beautiful Nubian art, to write grant proposals for her dream of becoming a documentary filmmaker. To make ends meet, she also worked evenings syncing sound for medical films on West 57th Street.

My neighbor, Robert Duvall, was editing his first movie, Angelo My Love – a film about Gypsies – and playfully insisted I had a Gypsy spirit. It sparked a fascinating friendship: I worked on films about everyday problems like back pain, while he focused on the world of Gypsies. That’s just the kind of unexpected mix you find in New York City.

Nair was eventually awarded a documentary grant. Her first film, So Far From India (1983), told the story of a New York City newsstand worker returning to India to visit his family. This film, like many of her later projects, explored the universal theme of finding home.

Nair explained she always aimed to share the stories of people who are often overlooked. She hadn’t planned a specific career path, but she was strategic about the stories she proposed. She focused on pitches that she knew others wouldn’t pursue, making that her unique approach.

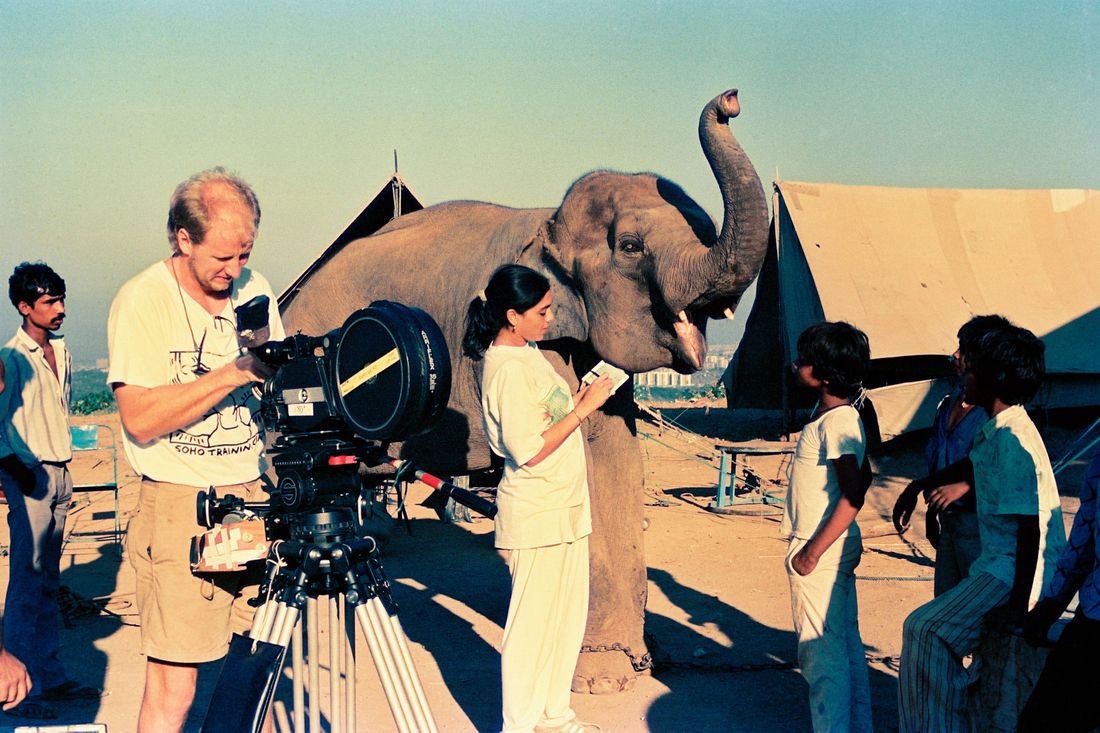

Two years after that, she created India Cabaret, a film about striptease dancers in Bombay. In 1987, she made Children of a Desired Sex, which explored the practice of using amniocentesis in India to learn the sex of a baby before it was born. However, by the mid-1980s, Nair felt she wanted to reach a wider audience and was eager to move beyond making documentaries. She started working on a feature film – with her collaborators Sooni Taraporevala and her then-husband, Epstein – about the lives of children living on the streets of Bombay.

Nair explained that many people believed the film was impossible to make, both due to its sensitive topic and her unique vision. She planned to blend fictional and real elements, and wanted to treat the child actors she cast—found on the streets—like established stars.

Taraporevala remembered thinking Salaam Bombay! would be a small, independent film. Although they didn’t have a lot of funding, director Mira Nair never mentioned it – she was raising money even as they filmed. The film came together remarkably quickly, something Taraporevala jokingly calls ‘Mira Magic.’ Just days after editing was finished, Salaam Bombay! premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, where it received a standing ovation, an audience award, and the Golden Camera prize. Vincent Canby of the New York Times described the film as having a ‘free-flowing exuberance.’ Nair was only 31 years old at the time.

She recalled returning from Cannes and having dinner with Epstein. They were living in a loft in the Lower East Side at the time. At their new favorite restaurant in Chinatown, she spotted Jim Jarmusch, who had previously won the Caméra d’Or award for his film Stranger Than Paradise. She said she simply shook his hand and gave him a hug. “It was amazing to have two Caméra d’Or winners together in Chinatown,” she noted, describing a feeling of friendly connection.

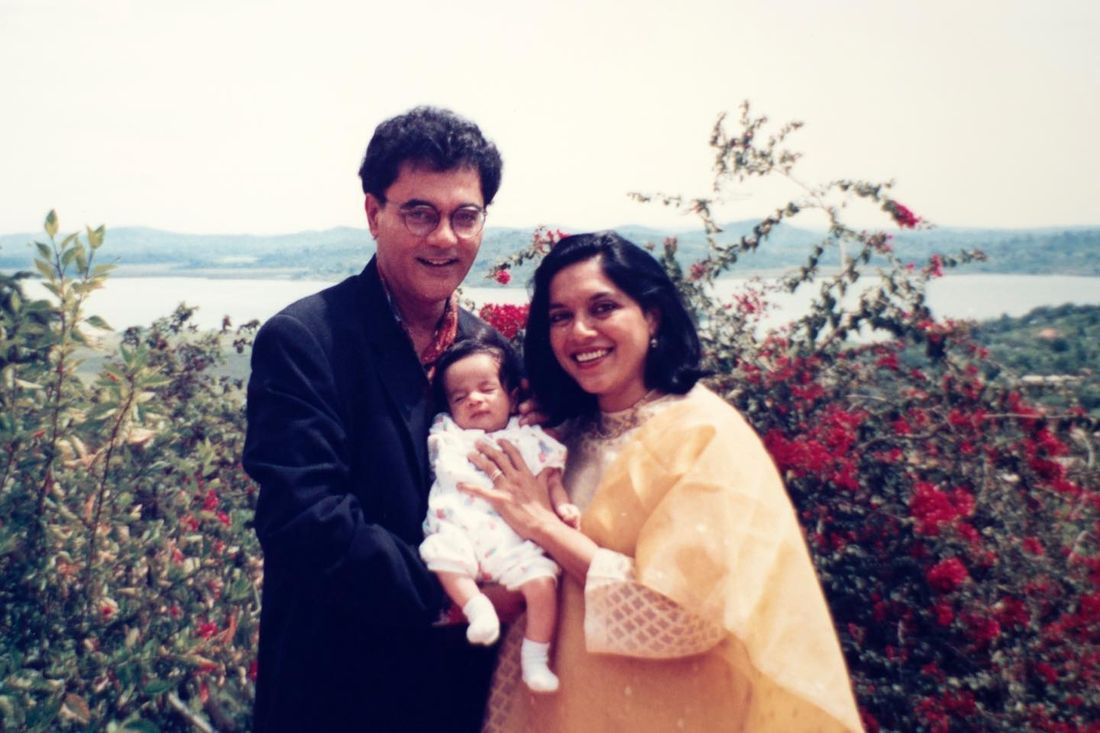

In 1990, Nair started working on Mississippi Masala, reuniting with collaborators Epstein and Taraporevala and beginning a partnership with producer Lydia Dean Pilcher. While researching the film – which tells the story of Asians expelled from Uganda by Idi Amin – she discovered the writings of scholar Mahmood Mamdani, who had extensively studied the expulsion.

While Mira Nair was filming in Kampala, Uganda, Mahmood Mamdani was hosting a conference about academic freedom. Filmmaker David Pilcher remembered a vibrant time, saying they’d spend their days shooting and their evenings discussing ideas with inspiring scholars – all while student protests were happening around them. It was during this exciting period that Nair and Mamdani fell in love. She divorced her then-husband, Epstein, married Mamdani, and shortly after became pregnant.

She and her husband, Mamdani, were living in a cozy, stylish apartment on Barrow Street in New York, which she really enjoyed. However, when she became pregnant, she realized that in her culture, new mothers rely on family support, and their small apartment couldn’t accommodate them. So, quite suddenly, they decided to move to Uganda when she was seven months pregnant.

Nair moved from New York City for the same reasons many people do now: the high cost of housing and childcare. She and her family bought a house in Kampala, Uganda, with a view of Lake Victoria – the same location where they’d filmed parts of Mississippi Masala. She described it as beautiful but basic, admitting it didn’t even have a kitchen. Their main reason for going was to be able to have their children nearby when she gave birth, a decision she now considers impulsive.

Zohran was born in Kampala a few months later, and the family returned home to a warm gathering of grandparents and friends. Taraporevala shared, “Having him born there was a wonderful decision – it was a truly peaceful and beautiful place.” She described a happy time with Mahmood, Mira, Baby Zohran, her in-laws, and her mother.

Now, Nair told me 34 years later, “people really curse me out. Because he can’t be president.”

Mira Nair was working on a film about the Buddha throughout her pregnancy, Zohran’s birth, and while she was breastfeeding. Although the film was never completed, the project deeply influenced how she remembers becoming a mother. She created a cozy space in her husband’s study – she affectionately called it the ‘milk bar’ – where she could nurse Zohran at night. Surrounded by a lamp and books, she would read Buddhist teachings and a poem about Prince Siddhartha’s life, reflecting on themes of balance, enlightenment, and the importance of compassion and connection – all central to the Buddha’s message.

She described her baby as generally very happy and not prone to crying, only remembering one instance of him being upset due to an ear infection. What she remembers most vividly, though, is his laughter. She, along with her husband Mahmood, used to secure him in a special seat at the dining table, and they’d all laugh together. She recalled his little legs shaking with excitement as he enjoyed the joyful atmosphere. They would simply sit and laugh, and she described this as their everyday life, however simple it may seem. It was pure, uncomplicated happiness.

Last summer, at his childhood home in Kampala, Zohran married the artist Rama Duwaji. During the wedding reception, Nair reminisced about their first year knowing each other, recalling a moment when she told Zohran, “I truly believe you have a Buddha-like quality within you.”

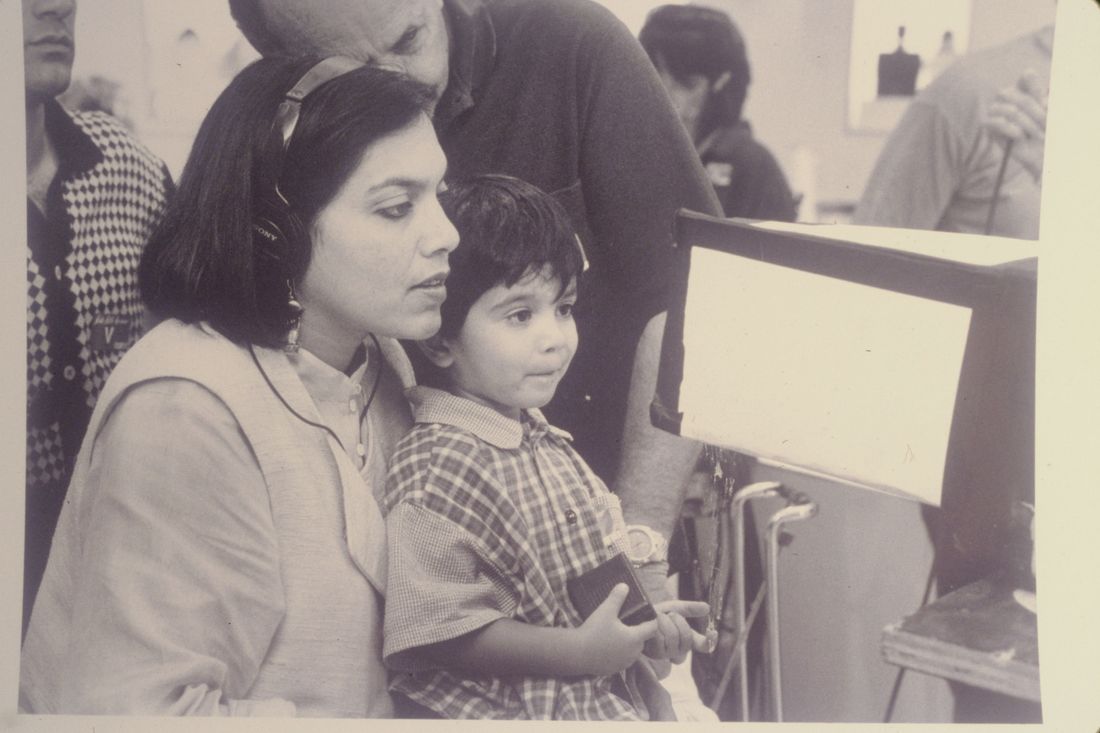

In the early years, Nair and her son, Zohru, were always together. Nair recalls Zohru accompanying her on film sets and during promotional events even when he was very young. She’s incredibly thankful to her mother and in-laws, who formed a strong support system and allowed her to continue working without interruption. For the first six years of Zohran’s life, they created a mobile home environment, accompanying her to every filming location. Nair would often work long, 15-hour days, but always return to a ready-made meal and a comfortable home thanks to their help.

Zohran grew up in a family where caring for others and working hard were equally important, and this deeply influenced him. As he explained, he doesn’t just think of his parents as individuals or as professionals, but as a couple who demonstrated that it’s possible—though challenging—to build a successful career and raise a family at the same time. He sees a hopeful possibility in their example.

Nair stressed that they made a point of including their son, Zohran, in their lives and work. They didn’t want him to feel disconnected. Frequent travel between Kampala, India, and New York meant Zohran grew up around airplanes, and because many of their flights were for work and covered by Hollywood, he often got to travel in first class.

It was the cutest thing! My son, Zohran, would always unbuckle himself as soon as the seatbelt sign went off. Then, still in diapers, he’d just toddle down the aisle, saying a quick ‘bye’ to me. He wouldn’t even look at the adults he passed, just politely offer his hand and scan the row for another kid. He’d keep going, row by row, until he found a playmate. I’d watch his little diapered bottom waddle over to the other child’s seat, and he’d be happy as could be for the rest of the flight! One time, a flight attendant saw him doing this and playfully nudged me, saying, ‘He’s going to be a politician!’ It was so true – he knew exactly how to work a room!

I was so thrilled when Mississippi Masala did well – Mira Nair said it helped her avoid that dreaded ‘second-film curse’! But things actually got more complicated for her after that. She was incredibly dedicated and proud of her consistent work ethic, but she admitted she was feeling the strain of trying to juggle everything. Her husband, Mahmood, was constantly traveling, teaching at universities in South Africa, India, and the US, and Mira was trying to build a film career while moving around a lot, often being far from major film hubs like the US and India.

In 1994, she directed The Perez Family, a film about the 1980 Cuban boatlift to Florida, featuring Marisa Tomei and Anjelica Huston. She explained she was drawn to the theme of exile and deeply inspired by Cuban narratives. However, she aimed for a realistic portrayal of Cuban culture, while the studio preferred a lighthearted romantic comedy. Unfortunately, The Perez Family wasn’t successful with critics or audiences. Her next film, Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996), a story about two 16th-century Indian women, also failed to gain traction.

Nair was in Cape Town, where her husband had just started teaching and was sparking debate with his plans to update the African-studies curriculum as South Africa transitioned from apartheid. She was leading filmmaking workshops in Asian and Black communities, teaching the Danish Dogme method – a way to create films with minimal resources. This led her to wonder if she could apply the same principles to her own life, asking herself, “If I’m teaching others to make something out of nothing, can I do it myself?”

The idea for Monsoon Wedding came about because Mira Nair needed funding for the film. In the spring of 2000, her agent, Bart Walker, suggested she go to the Cannes Film Festival to try and secure financial backing. Walker worked tirelessly to schedule meetings, recalling he booked appointments with leading companies every hour for three days. Nair traveled from New York, where her colleague Mahmood had recently taken a position at Columbia University. After arriving in Cannes, Walker encouraged her to quickly freshen up before the packed schedule. Just twenty minutes later, Nair rushed back to the lobby to tell him the film was fully financed. She’d actually secured funding during a chance encounter in an elevator with the head of IFC Films, giving him a quick pitch that led to their investment.

In 2000, Mira Nair filmed Monsoon Wedding in just 30 days in New Delhi, using her friends and family as actors. The film tells a vibrant and lively story about a large Punjabi wedding. The cast spoke a mix of English, Hindi, and Punjabi, sometimes within the same sentence. Nair anticipated distributors might be concerned about subtitling such a multilingual film, but she was confident audiences would connect with the natural, realistic dialogue. She believed they would understand, and she was proven right.

The film’s success opened doors to larger projects. She was offered a $50 million adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, with Reese Witherspoon, and even considered directing a Harry Potter movie. However, her teenage son suggested she adapt Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake instead, which she ultimately directed in 2006. Nair noted that her son, Zohran, experienced all of these events firsthand.

Mamdani wasn’t sure exactly when he first understood his mother’s profession. As a child, he knew Pilcher and Taraporevala simply as “Lydia Maasi” and “Sooni Maasi” – terms of endearment for maternal aunts – and learned about their work later on. He was ten years old when Monsoon Wedding became incredibly popular, and he remembers watching it and spotting relatives and his grandmother among the actors.

He remembers realizing the significance of things around the time he was in high school. The moment that really stood out for him came with the film Mississippi Masala. He said that watching it after college was a powerful experience. He was struck by how much he loved the film, and also by the fact that he wouldn’t be the person he is today without it. He explained that simply enjoying the film would have been enough, but it meant so much more than that.

The new mayor appears remarkably at ease in front of the public, and for good reason – he’s no stranger to attention. Photos exist of him as a baby, riding on his father’s shoulder at the premiere of Mississippi Masala. He was featured in national magazines, including a 2002 New Yorker profile where he was described as a charming and talkative child. He even appeared in New York magazine, listing FIFA and Sim-City as gifts he hoped to receive. When he was 15, his father shared a story with The Believer about his son’s confident voicemail greeting: “Hi, you’ve reached the Ugindian president of the United States, otherwise known as the Brownest Man on Earth. He’s not here to take your call.” His father recounted being both exasperated and proud, noting that everyone loved his son’s habit of referring to himself in the third person.

The fact that Mamdani came from a privileged background was highlighted during his campaign, and to some extent, that was true. However, it’s ironic to suggest he unfairly used his family connections in a city where wealth and power often come from inherited fortunes. While Mamdani benefited from attending a private school and having successful, well-compensated parents – a Columbia professor and a Hollywood director – the claim that he had an excessively privileged upbringing, as one Democratic strategist put it, is an exaggeration. His mother, Mira Nair, even joked that her accountant asked where all her supposed billions were.

The family’s true wealth wasn’t financial, but intellectual and creative, connecting Mamdani to influential thinkers and those who supported them. He moved in circles with journalists, writers, and the educated middle and upper classes – people who were often connected to, and sometimes reliant on, wealthy patrons. For example, a filmmaker documenting poverty in Bombay likely wouldn’t be able to fund a personal, ambitious project – like a film about their family – without securing investment from powerful sources, perhaps even while attending film festivals like Cannes.

Raising money is always challenging, according to Taraporevala, who praised Nair’s experience and noted that Zohran has learned a lot by observing it all. Taraporevala also highlighted that both Nair and Zohran are skilled at connecting with people from diverse backgrounds and cultures.

Mamdani’s unique ability allows him to connect with even the most unlikely people, like Donald Trump. His mother, Nair, revealed in December that her son had meticulously prepared for his meeting with the president, though he doesn’t openly discuss it. Nair also shared a guiding principle of her work in film: “Focus on the result, not the effort. My role is to make everything appear effortless, even if it wasn’t.” This suggests a talent for making difficult things seem easy may also come from her.

Ali Sethi, a friend of the Mamdani family and someone Nair mentored, described the experience of immigrants like himself who make New York their home. He explained that they’re constantly balancing different aspects of their lives – their professional lives, cultural heritage, family, and various social circles – and adjusting how they present themselves in each. Sethi, who first met Nair as a Harvard undergraduate and has since collaborated with her and performed at a Mamdani event, said that both she and her mother have a remarkable ability to navigate these potentially awkward transitions with grace and charm, making them seem effortless and appealing.

Despite being very involved in their son’s life, Nair emphasized that she and Mahmood never overly interfered or pushed him towards conventional achievements. Their main priority, she explained, was simply his education and understanding of the world. They wanted him to learn, read, and write, and that was all that mattered.

She admitted, with a touch of regret, that she’d probably overstepped when it came to her son’s college applications. Zohran hadn’t wanted to go to Columbia, joking that he’d be taught by family friends. He also wasn’t accepted, even though his father worked there. However, she’d pushed him to apply to Harvard, as she and her husband had both attended. But she always believed Harvard was only a good fit if a student truly wanted to be there, and Zohran didn’t. He was accepted, but with a year’s delay, and didn’t even share the news with her. Her other son, Mamdani, was determined to go to Bowdoin College in Maine. “That was the one time I was really surprised,” she said, “but he wanted to forge his own path, which is wonderful.”

Mamdani chuckled, remembering his mother’s focus on education. He recalled that when he ran for Assembly, she’d jokingly asked if a bachelor’s degree was enough to get him there.

“No, Mamma,” he assured her, “I don’t need a Ph.D. to be in the Assembly.”

Nair shared this story with me as well, and she was adamant it all started as a joke. She explained she was playfully mimicking a stereotypical aunt, and would say, ‘But Beta, what about your graduate degree?’ It was just her doing a funny impression.

Her son, in his twenties, playfully called her “my fellow bachelor,” which reminded her that she only had a bachelor’s degree – something she admitted she’d completely forgotten.

Mamdani explained that his family has always been loving and supportive of his goals, but they’ve never hesitated to share their honest opinions. He used the example of a child pursuing a creative career, like art. He described how a parent might initially be encouraging, then later check in to see how things are progressing, asking something like, ‘How’s that going?’

He recounted his short time as a rapper, going by the name Young Cardamom. He and his friend, Abdul Bar Hussein, created a song called “#1 Spice” – with lyrics like “Bring the flavor to the fish / Bring the flavor to the rice” – which appeared on the soundtrack for his mother’s 2016 film, Queen of Katwe. In 2019, he released a solo track, “Nani,” dedicated to his grandmother Praveen, featuring the bold lyrics, “I’m your boss, I’m your fuckin’ Nani / Got a doctorate, bitch, so don’t fuckin’ try me.” The music video starred the well-known Indian chef, Madhur Jaffrey.

He recalled his father asking about his music near the end. “It wasn’t exactly those words,” he explained, “but it felt like he was asking how many people were listening to my songs on SoundCloud.”

Nair was relieved her son didn’t become a rapper, but she also clarified that she always enjoyed his music.

Zohran’s mother, Nair, described him as an incredibly dedicated worker, especially during his mayoral campaign. Shortly after his wedding ceremony (nikkah) in Dubai in late December 2024, he immediately returned to New York to continue working. Nair recalled pleading with him to stay and enjoy time with his new wife, suggesting a weekend getaway instead of working during the Christmas season. However, Zohran was unwavering, driven by a feeling that they always needed to do more.

At the beginning of the campaign, she questioned whether success was even achievable. She recalled being told her own accomplishments were impossible, and remembered making the film Salaam Bombay! at just 30 years old. She also pointed out that Mahmood had published two books, one of which was used in courses at Harvard, before he turned 30.

She noted it was remarkable to witness such events during her lifetime and the lifetime of someone young. She also expressed surprise at his behavior, particularly during the debates. He often corrected people on how to pronounce his name, and she found this impressive. She herself always insisted on correct pronunciation, even on major talk shows, firmly stating it was pronounced “MEE-ra NYE-er” – like the word “fire” – and even patiently guided Bill Moyers on the proper way to say it.

Zohran’s determination, she explained, stemmed from a fundamental belief: that they deserve to be acknowledged. He wants others to simply recognize his existence and say his name. This plea for recognition was central to his campaign. Nair pointed out that New Yorkers – not just Muslims, but also Bangladeshis and Pakistanis – hadn’t traditionally been considered a significant voting bloc. People are returning to the city to vote for him because he makes them feel valued and understood – like he truly sees them.

Wasn’t this her signature as a filmmaker – giving a voice and presence to those who were previously ignored? She thought about it for a moment. “Yes,” she admitted. “I wanted to bring these people into the light, make them seen and heard. And now, here we are.”

Nair proudly described herself as a dedicated volunteer, or “canvassing mom.” She spent three days a week, from January to June, going door-to-door in different neighborhoods. She witnessed the candidate’s growing popularity, going from being unknown to widely liked, and ultimately to being enthusiastically supported by June, with people eager to vote for him. She described the experience of walking through neighborhoods as incredibly positive, saying people’s reactions felt like warm, bright sunshine.

She firmly believes Zohran will be a successful leader. She noted that his campaign showed how he’d govern – with creativity, innovation, and genuine care for others. Nair, who always advises film students to value their teams, feels confident in the people Zohran has chosen to work with. “I’m impressed with his team,” she said. “He’s surrounded himself with the best.”

She also feels comforted by his wife, whom she describes as a remarkable and strong woman – confident, impressive, and truly special. Nair shared that she immediately liked Duwaji, and was particularly relieved to admire her art. While she appreciates Duwaji as a person, she emphasized how important it was to also connect with her work. She loves both Duwaji’s art and her personality deeply.

I wondered if Nair’s father, who passed away in 2012, would have been proud of his grandson’s success. Nair quickly went to find a painting she’d recently brought from India—a gift her father had given Zohran on his third birthday. The painting depicted British India, including present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, before the partition that tragically separated many families, including her own, from their roots. Painted over the map was a picture of young Zohran, and beneath it were two messages: “With love from Nana” (Hindustani for maternal grandfather) and “My friends will be these three, and of each other too.”

Nair expressed amazement that his father believed Zohru could bring together three different nations. He explained that when his father served as an assemblyman representing Astoria, his constituents included people from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. In a way, Zohru became the representative of all those communities – it was truly remarkable. This is what his father had always hoped for, and Nair believes his father would be incredibly proud to see it happen.

Mira Nair, like Jhumpa Lahiri, feels at home in both Queens and Manhattan. Nair often writes about the making of her films, and in an essay included in a later version of The Namesake, she explained how Lahiri’s novel explores places she knows well: Calcutta, Cambridge, and ultimately, New York City. Nair described Lahiri’s New York as a sophisticated world of lofts, Ivy League connections, art, political activism, and weekend getaways with established families – a far cry from typical immigrant neighborhoods like Little India or Jackson Heights. She wrote that this was the city she’d lived in since 1978 and where she truly learned to observe the world.

Nair explained that her son’s diverse pursuits all feel connected, like they stem from a shared foundation. She believes this unity within variety is a key part of his approach, both in his political campaign and his overall thinking, and that it’s something they developed together over time.

Read More

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

- ‘Stranger Things’ Creators Break Down Why Finale Had No Demogorgons

2026-02-10 13:03