Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are pushing the boundaries of efficient AI model training by strategically reducing computational load at the neuron level.

A novel activation function combining weight and activation sparsity, leveraging the Venom format and soft-thresholding, accelerates large language model pre-training by optimizing transformer feed forward networks.

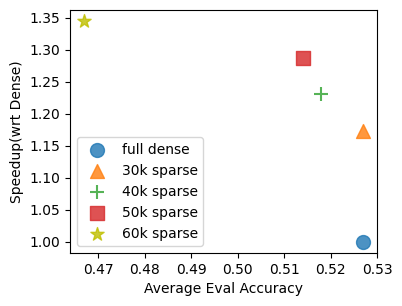

Despite the rapid growth of Large Language Models (LLMs), pre-training remains computationally constrained by intensive matrix multiplications. The work ‘To 2:4 Sparsity and Beyond: Neuron-level Activation Function to Accelerate LLM Pre-Training’ addresses this bottleneck by introducing a strategy leveraging both weight and activation sparsity-specifically, 2:4 weight sparsity coupled with Venom-formatted activation sparsity-within the Transformer’s feed forward network. This approach achieves end-to-end training speedups of 1.4 to 1.7x while maintaining comparable performance on standard benchmarks, and is applicable to current NVIDIA GPUs. Could this combination of sparsity techniques unlock even greater efficiencies and scalability for future LLM development?

The Computational Limits of Scale

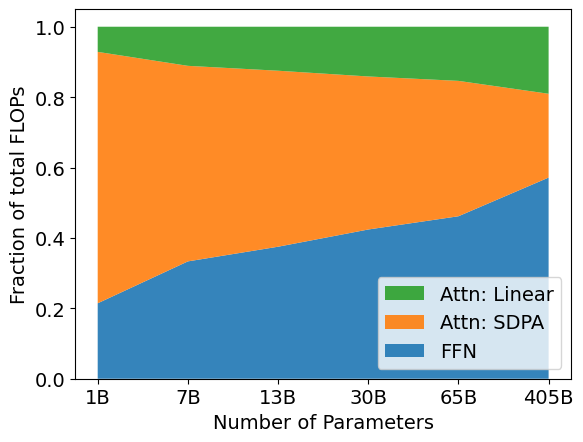

The remarkable capabilities of Large Language Models are paradoxically constrained by the sheer volume of computation required to operate them, specifically through the repeated execution of matrix multiplication during the training process. Each parameter update necessitates multiplying enormous weight matrices – often containing billions of elements – with input data, a process that quickly becomes a significant bottleneck as model size increases. This computational burden isn’t simply a matter of needing faster processors; the scaling of computational cost with model size is fundamentally limiting, making it increasingly difficult and expensive to train even incrementally larger and more sophisticated models. Consequently, research is increasingly focused on innovative strategies to reduce this dependence on dense matrix operations, exploring methods such as sparsity, quantization, and alternative architectures that promise to unlock the full potential of \text{LLMs} without being crippled by computational demands.

The computational burden of large language models is intrinsically linked to the structure of their core components: weight matrices. These matrices, which store the learned parameters of the model, are typically ‘dense’, meaning the vast majority of their elements are non-zero and require individual calculation during every operation. As model size increases – demanding more parameters to capture nuanced relationships in data – these matrices grow exponentially, quickly overwhelming available computational resources. This density directly limits scalability; doubling the model size doesn’t just double the computation, but potentially squares or cubes it. Consequently, progress towards increasingly complex and capable models is actively hindered, not by a lack of algorithmic innovation, but by the sheer practical difficulty of performing the necessary matrix multiplications within reasonable time and energy constraints.

The pursuit of increasingly capable Large Language Models is bumping against the constraints of conventional computational approaches. While techniques like distributed training and specialized hardware – including GPUs and TPUs – have delivered substantial gains, their effectiveness is diminishing as model sizes continue to swell. These optimizations primarily address the speed of existing matrix operations, rather than the fundamental cost inherent in multiplying massive, dense weight matrices. Consequently, further improvements based solely on these methods are yielding smaller and smaller returns, suggesting a need to move beyond simply accelerating current architectures. The future of LLM development likely requires exploring radically different model designs – such as sparse models, mixture-of-experts systems, or entirely new algorithmic approaches – to circumvent the limitations of traditional dense matrix computations and unlock the potential for truly scalable artificial intelligence.

Sparsity: Pruning for Efficiency

Sparsity reduces computational cost in large language models by leveraging the principle that many matrix operations involve multiplications by zero. Introducing zero-valued elements – effectively creating sparse matrices – directly minimizes the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) required for computations like matrix multiplication. Since most hardware architectures perform calculations regardless of whether operands are zero, sparse computations require specialized algorithms and hardware to avoid these unnecessary operations. The computational savings are proportional to the percentage of zero-valued elements introduced; a matrix with 90% sparsity requires approximately 10% of the FLOPs compared to a dense matrix of the same dimensions, assuming efficient sparse matrix implementations are utilized. This reduction in FLOPs translates directly into lower energy consumption and faster inference times.

Weight sparsity reduces computational load by eliminating connections – specifically, setting a proportion of the weight matrix elements to zero – thereby decreasing the number of multiply-accumulate operations required during inference and training. Conversely, activation sparsity focuses on zeroing out a percentage of activations within each layer, reducing computations in the forward pass by skipping operations involving these zeroed activations; this is often achieved through techniques like ReLU or other thresholding functions. While weight sparsity permanently alters the model’s parameters, activation sparsity is dynamic, varying with each input. Both approaches contribute to computational savings, but target different components of the LLM architecture and require distinct implementation strategies.

Effective application of sparsity in large language models requires careful calibration beyond simple weight removal. Reducing the number of parameters through sparsity directly impacts model size and can yield computational savings; however, aggressive sparsity can degrade performance. The optimal balance depends on the specific model architecture, dataset, and intended application, necessitating techniques like iterative pruning and fine-tuning to maintain accuracy while maximizing efficiency gains. Quantifying this balance involves monitoring trade-offs between model size, inference speed, and key performance indicators, and often requires experimentation with varying sparsity levels and retraining strategies to avoid significant performance drops.

Semi-Structured Sparsity: A Pragmatic Approach

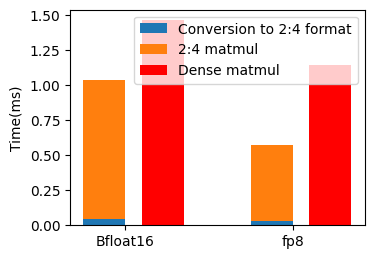

Fine-grained sparsity, where individual weights are set to zero, maximizes model compression but presents challenges for hardware acceleration due to irregular memory access patterns. Semi-structured sparsity formats, such as 2:4 and V:N:M (Venom) sparsity, offer a compromise by enforcing structure on the zeroed weights. 2:4 sparsity, for example, eliminates every other weight in both rows and columns of a weight matrix. Venom sparsity generalizes this by removing blocks of weights according to a V:N:M ratio, where V is the number of consecutive zeroed blocks, N is the block size, and M is the number of blocks within a larger group. This structured approach allows for efficient computation using specialized hardware, like Sparse Tensor Cores, by reducing the number of required operations and improving data locality compared to fully dense or fine-grained sparse matrices.

Semi-structured sparsity formats, unlike unstructured sparsity, introduce regularity in the placement of non-zero elements within weight matrices. This structure is crucial for hardware acceleration, particularly with Sparse Tensor Cores which are designed to efficiently process matrices with predictable sparsity patterns. The Venom (V:N:M) sparsity format, a specific type of semi-structured sparsity, achieves a General Matrix Multiplication (GEMM) speedup ranging from 6 to 8 times faster than equivalent dense GEMM operations on standard hardware. This performance gain is a direct result of the hardware’s ability to exploit the imposed structure, reducing the number of required computations and memory accesses.

Weight sparsity can be implemented through techniques like soft thresholding, which selectively sets weights to zero based on their magnitude. Simultaneously, activation sparsity can be induced by employing squared ReLU (ReLU(x) = max(0, x)^2) as the activation function; this approach can achieve up to 90% sparsity in activations. These methods complement semi-structured sparsity formats by further reducing the number of operations required during inference and training, leading to increased computational efficiency when combined with specialized hardware acceleration.

Llama-3: Sparsity in Practice

The Llama-3 model represents a substantial leap forward in large language model design through the strategic implementation of sparsity. This approach intentionally introduces ‘emptiness’ into the network-reducing the number of active connections-without significantly compromising performance. By focusing computational resources on the most crucial parameters, Llama-3 achieves notable gains in both speed and efficiency. This isn’t merely about shrinking the model; it’s about intelligent pruning that maintains accuracy while dramatically lowering the demands on processing power and memory. The result is a model capable of faster inference and training, making advanced language capabilities more accessible and deployable across a wider range of hardware configurations – a key step towards democratizing AI technology.

The efficiency of training and deploying large language models hinges on overcoming computational bottlenecks, and Llama-3 addresses this through a combination of pipeline parallelism and sparse matrix computations. Pipeline parallelism divides the neural network into stages, allowing multiple stages to process different data samples concurrently – much like an assembly line. Simultaneously, sparse matrix computations reduce the number of calculations required by focusing on the most important connections within the network. This is particularly effective when used with large-scale datasets, such as the DCLM Dataset, where traditional dense matrix operations become prohibitively expensive. By strategically identifying and pruning less critical parameters, Llama-3 significantly lowers memory requirements and accelerates both the training process and the speed of generating text, without substantially sacrificing model accuracy.

Llama-3 distinguishes itself through a comprehensive approach to sparsity, extending beyond simple weight pruning to encompass both activations and key architectural elements like Feed Forward Networks. This multi-faceted strategy dramatically enhances computational efficiency; benchmarks reveal an end-to-end speedup of 2.2x during both training and inference. Crucially, this performance gain isn’t achieved at the expense of accuracy; the implementation of soft-thresholding ensures a minimal loss degradation of only 0.03 per individual weight, preserving the model’s predictive capabilities. By strategically reducing the number of active parameters at multiple levels, Llama-3 establishes a new benchmark for large language model efficiency, paving the way for more accessible and sustainable AI development.

Beyond Efficiency: Towards More Intelligent Networks

Beyond simply accelerating computation, the deliberate introduction of sparsity into large language models offers a pathway towards enhanced generalization and robustness. By strategically eliminating redundant parameters and connections – effectively creating a network with ‘gaps’ – models are compelled to learn more resilient and meaningful representations. This process mirrors biological neural networks, where selective pruning strengthens crucial connections and discards noise. The resulting sparse architectures are less prone to overfitting to training data, allowing them to perform better on unseen examples and exhibit greater stability when faced with noisy or adversarial inputs. This increased robustness isn’t merely about error reduction; it suggests a deeper understanding of underlying patterns, fostering models that are not just efficient, but genuinely more intelligent in their capacity to adapt and generalize.

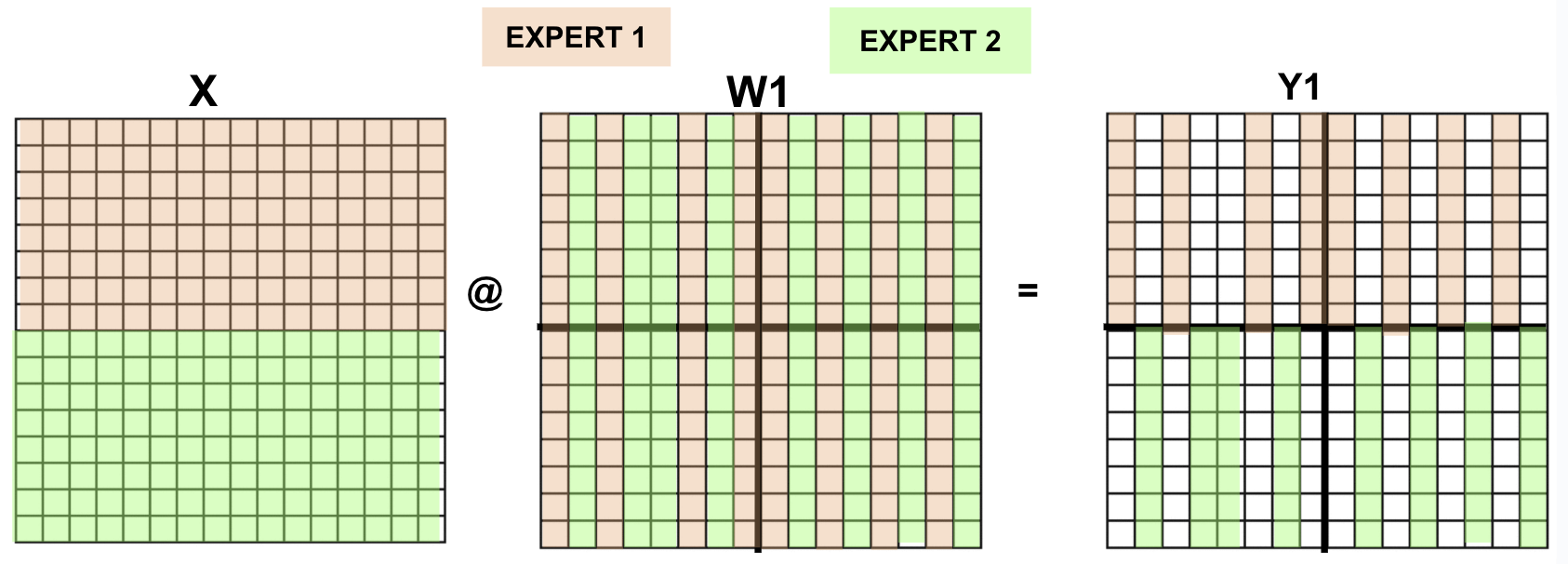

The convergence of sparse neural networks and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) routing at the neuron level presents a pathway towards significantly more adaptable and efficient large language models. Traditional MoE approaches distribute workload across numerous experts, but combining this with sparsity – strategically removing less critical connections – refines this process. This synergy allows models to dynamically allocate computational resources only to the most relevant parts of the network for a given input, increasing specialization and reducing overall processing demands. The result is a system capable of handling diverse tasks with greater precision and speed, as only a select few neurons actively contribute to each computation, fostering a more nimble and resource-conscious artificial intelligence.

The future of large language models hinges on advancements in sparsity, promising a shift towards AI systems that are not only powerful but also ecologically sound and broadly available. Current models demand substantial computational resources, limiting access and contributing to significant energy consumption; however, ongoing research into sparse LLMs – those with a drastically reduced number of active parameters – aims to address these limitations. By strategically pruning connections and focusing computational effort, these models can achieve comparable, or even superior, performance with a fraction of the resources. This pursuit of sparsity isn’t merely about efficiency; it’s about enabling more widespread access to AI technology, fostering innovation, and building a more sustainable future where intelligent systems can operate within planetary boundaries. Ultimately, continued exploration of sparse architectures is poised to unlock a new era of intelligent, equitable, and environmentally responsible AI.

The pursuit of efficiency in large language model training, as detailed in this work, necessitates a rigorous pruning of complexity. The authors demonstrate this through the implementation of 2:4 sparsity, optimizing matrix multiplications within the transformer feed forward network. This aligns with Kernighan’s observation: “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” The inherent difficulty in managing complexity is evident; a deliberately sparse structure, though initially demanding, ultimately eases the burden on computational resources and allows for a more manageable, and thus debuggable, system. The Venom format and soft-thresholding serve as mechanisms to enforce this clarity, reducing cognitive load and improving overall performance.

Beyond Reduction

The pursuit of efficiency in large language models invariably circles back to a simple truth: a system that needs acceleration has already failed, at least partially. This work, by introducing further reduction via combined weight and activation sparsity, moves closer to that ideal, yet reveals how much remains obscured. The Venom format, and the application of soft-thresholding, are not endpoints. They are merely more refined tools for dismantling redundancy. The lingering question is not how to add complexity to achieve sparsity, but why such complexity was present in the first place.

Future efforts should not focus solely on novel sparsity patterns or optimization techniques. A more fundamental examination of the feed-forward network’s architecture is required. If the core design necessitates such aggressive pruning to achieve viability, it suggests a deeper flaw. Clarity is courtesy; a truly efficient system should not require a convoluted process of subtraction to reveal its underlying simplicity. The focus should shift toward intrinsically sparse representations, designs that prioritize essential connections from inception.

Ultimately, the metric of success will not be measured in FLOPS reduced, but in conceptual weight lifted. A sparse model is not simply a fast model; it is a model that more closely reflects the essential structure of the information it processes. The goal, then, is not to achieve sparsity, but to recognize it, to build systems that inherently embody it, and to finally abandon the illusion that more is always better.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06183.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

- Every Death In The Night Agent Season 3 Explained

2026-02-10 08:33