Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theoretical framework leverages the Moyal distribution to connect microscopic transmission events with the large-scale patterns observed in pandemic outbreaks.

This review demonstrates how the Moyal distribution provides a unified approach to understanding epidemic dynamics, incorporating stochasticity, superspreading, and social friction.

Traditional epidemiological models struggle to capture the extreme volatility and heavy-tailed events characterizing real-world outbreaks. This is addressed in ‘From Stochastic Shocks to Macroscopic Tails: The Moyal Distribution as a Unified Framework for Epidemic Dynamics’, which proposes a novel framework bridging microscopic transmission dynamics with macroscopic outbreak patterns via the Moyal distribution. By treating viral spread as a stochastic collision process, the authors demonstrate that the emergence of “social friction” in pandemic waves is directly linked to microscopic “collision shocks,” successfully capturing superspreading events missed by standard models. Could this approach provide a more robust basis for public health planning, shifting focus from deterministic averages to managing inherent epidemic volatility?

Beyond Deterministic Models: Embracing the Realities of Epidemic Spread

Traditional epidemiological modeling, exemplified by the susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model, frequently operates under deterministic assumptions, meaning it predicts a single outcome based on initial conditions and fixed parameters. However, this approach struggles to accurately represent the inherent unpredictability of outbreaks. The SIR model, and others like it, often treat transmission as a smooth, continuous process, failing to fully account for the role of chance events – a single superspreading event, for example, or localized variations in contact rates. This simplification can lead to significant discrepancies between model predictions and real-world observations, especially when dealing with novel pathogens or populations exhibiting highly variable behavior. While useful for illustrating broad epidemiological principles, the deterministic nature of these models limits their ability to forecast outbreaks with precision or to effectively guide targeted interventions in the face of substantial uncertainty.

Traditional epidemiological modeling often presents a simplified view of disease transmission, frequently overlooking the inherent randomness that characterizes outbreaks in real-world populations. This simplification manifests as a failure to accurately capture the substantial variability observed in infection rates, reproductive numbers, and outbreak sizes. Consequently, predictions generated by these models can deviate significantly from actual disease trajectories, hindering the effectiveness of public health interventions. The assumption of homogeneity – that all individuals are equally susceptible and infectious – proves particularly problematic, as it disregards the diverse factors influencing transmission, such as varying contact patterns, individual immune status, and localized environmental conditions. Ultimately, this disconnect between model assumptions and biological reality limits the utility of these models for forecasting outbreaks and optimizing control strategies, necessitating the development of more nuanced approaches that incorporate stochasticity and individual-level heterogeneity.

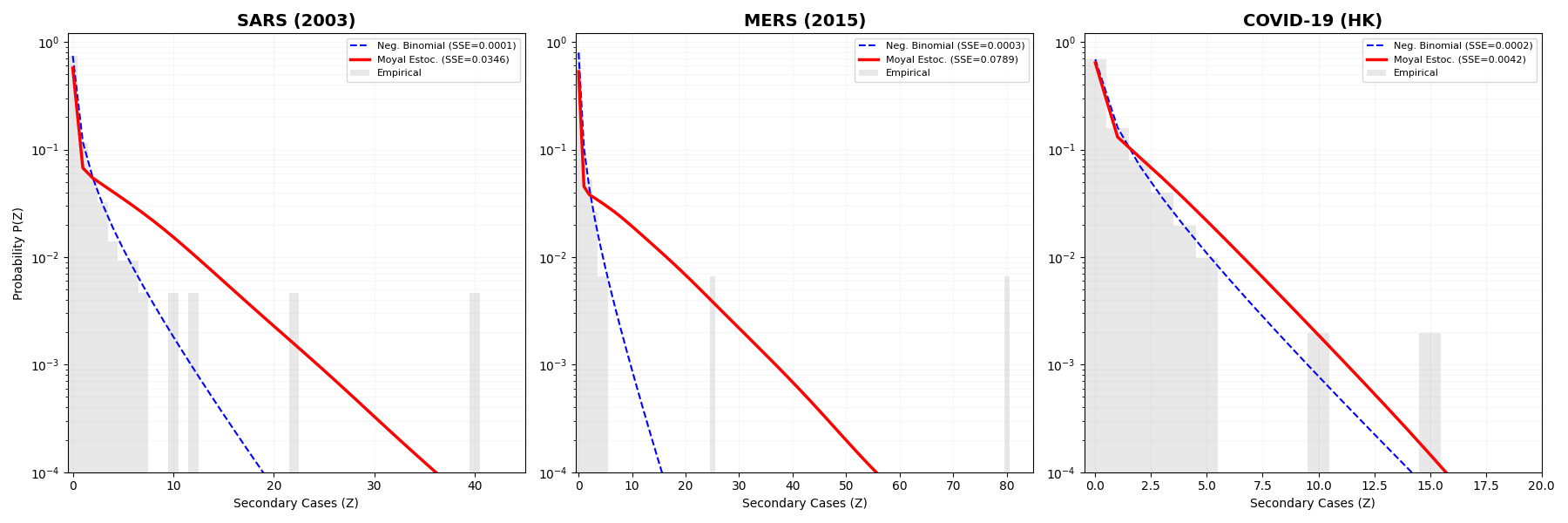

Traditional epidemiological modeling frequently employs statistical distributions like the Negative Binomial to account for overdispersion – the observation that disease incidence varies more than expected under purely random processes. However, these approaches often represent a simplification of the underlying complexities of transmission dynamics. While useful for capturing some degree of variability, the Negative Binomial, and similar methods, struggle to fully encapsulate the inherent stochasticity arising from individual-level heterogeneity, environmental fluctuations, and the cascading effects of chance encounters. This limitation becomes particularly evident when modeling outbreaks exhibiting substantial variability in superspreading events or influenced by behavioral changes, ultimately hindering the predictive accuracy of interventions based on these models and underscoring the need for more sophisticated approaches capable of capturing the full spectrum of stochastic influences on disease spread.

Understanding disease spread requires moving beyond the assumption that all individuals contribute equally to transmission. Current epidemiological modeling often overlooks the significant variability in how infectious any single person is – factors like differing immune responses, behavioral patterns, or even social connectivity dramatically alter an individual’s potential to spread a pathogen. Furthermore, localized stochastic effects – random fluctuations in contact rates or environmental conditions – introduce unpredictable elements that deviate from average trends. These effects, while seemingly minor at the individual level, accumulate and can substantially influence outbreak dynamics, making precise prediction difficult. Accurately representing this heterogeneity and inherent randomness is crucial for developing more robust and realistic models capable of informing effective public health strategies, and necessitates incorporating concepts from stochastic processes and individual-based modeling.

A Stochastic Framework: Modeling Epidemics with the Moyal Distribution

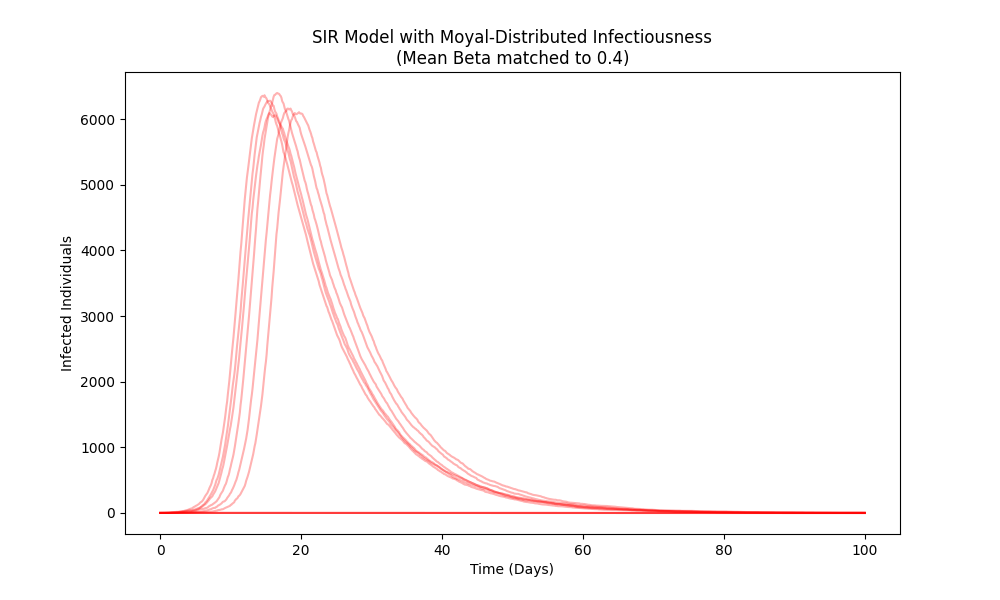

The Stochastic Moyal-SIR model represents an advancement over the standard Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model by incorporating stochasticity in the infectiousness of individuals. Traditional SIR models assume a fixed transmission rate; however, real-world transmission is subject to inherent variability. This new model utilizes the Moyal distribution to characterize this stochasticity, allowing for a probabilistic description of the infection process. Specifically, the model assigns a probability distribution to the transmission rate for each individual, rather than a single deterministic value, thereby acknowledging that not all infected individuals transmit the disease with equal efficiency. This approach moves beyond deterministic compartmental modeling and enables the simulation of multiple outbreak realizations, capturing a more realistic representation of epidemic dynamics.

The Moyal distribution, originally developed in statistical mechanics to model energy loss phenomena, provides a mechanism for representing the non-Gaussian behavior frequently observed in epidemic curves. Traditional epidemiological models often assume a normal distribution of infectiousness, which underestimates the probability of extreme events such as superspreading or rapid outbreak acceleration. The Moyal distribution, possessing heavier tails than the normal distribution, allows for a higher probability of these extreme outcomes. Specifically, the distribution’s ability to model broader deviations from the mean infectiousness rate accounts for the observed ‘fat tails’ in outbreak data, where a disproportionately large number of individuals exhibit either very high or very low transmission rates. This is particularly relevant in capturing the heterogeneity of infectiousness within a population and accurately reflecting the likelihood of rare, but impactful, transmission events.

The Stochastic Moyal-SIR model quantifies ‘Social Friction’ – encompassing factors such as mask-wearing, social distancing, and vaccination campaigns – by directly relating it to the width parameter βw of the Moyal distribution. This parameter effectively represents the standard deviation of individual infectiousness, with larger values indicating greater heterogeneity and potentially reduced overall transmission rates. Critically, analysis demonstrates an inverse correlation between βw and variant transmissibility; more transmissible variants exhibit a narrower Moyal distribution (smaller βw), signifying a more uniform and efficient infection rate among individuals, while interventions increasing βw can model a reduction in effective transmissibility. This provides a quantifiable metric for evaluating the impact of interventions on slowing epidemic spread.

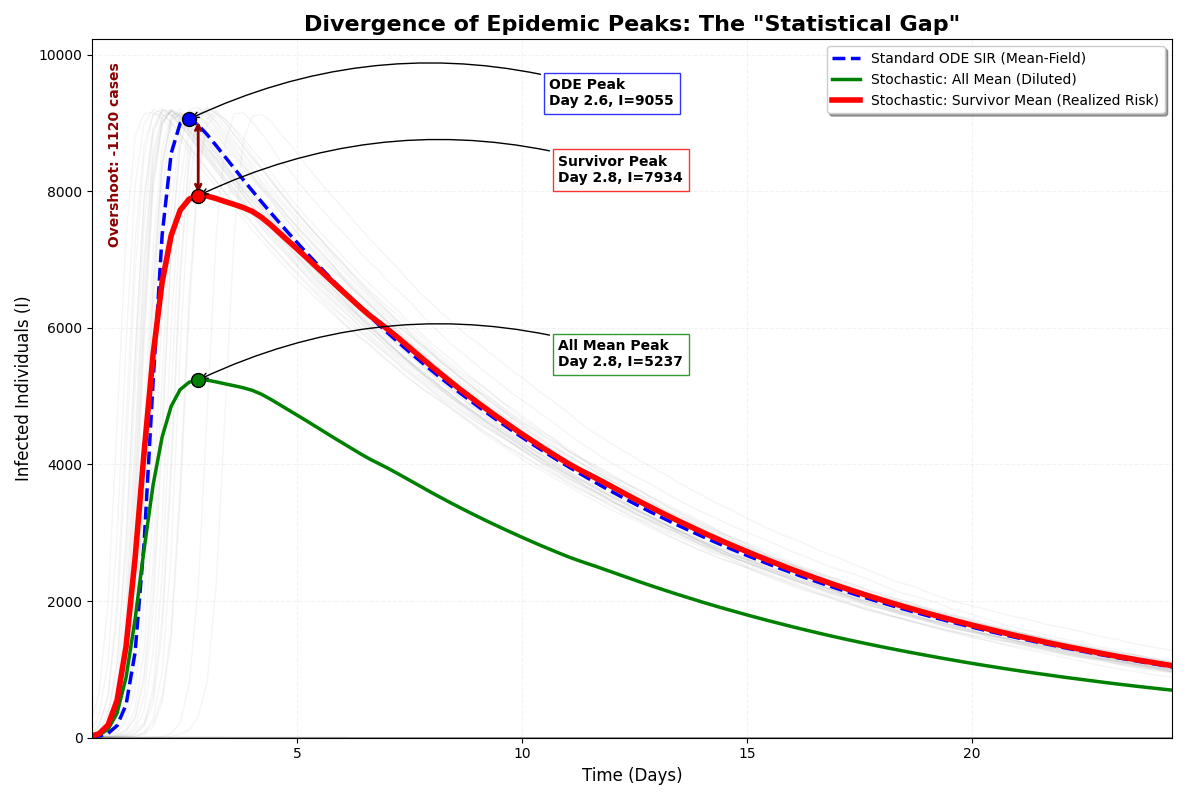

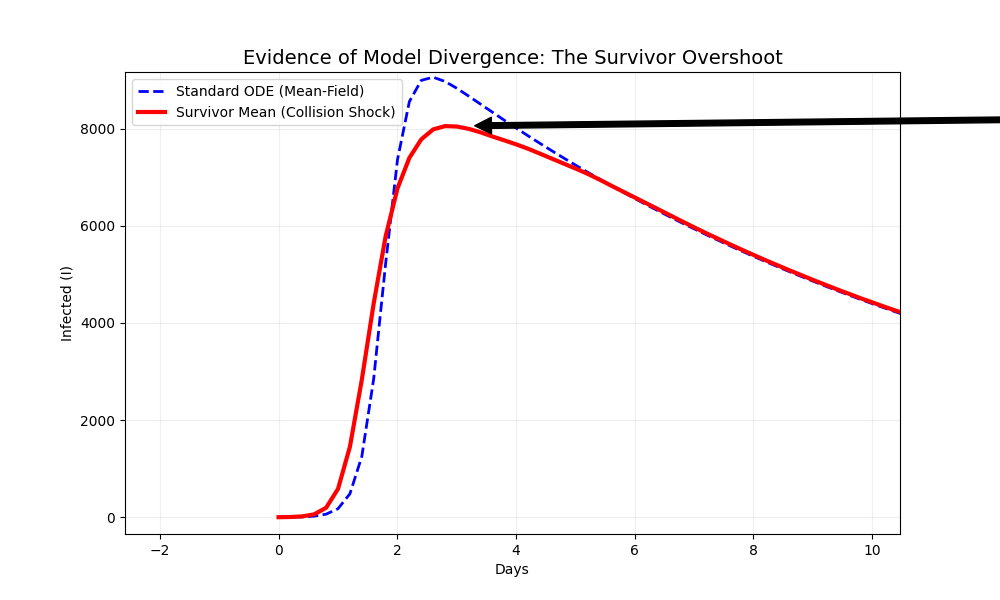

The Stochastic Moyal-SIR model utilizes ‘All Mean’ and ‘Survivor Mean’ calculations to comprehensively represent potential outbreak scenarios. ‘All Mean’ quantifies the average outcome across all possible outbreak realizations, encompassing both extinguished and widespread transmission events. Conversely, ‘Survivor Mean’ focuses specifically on the average outcome conditional on the outbreak surviving beyond initial stages, providing a measure of the expected scale of transmission given that an outbreak persists. This distinction allows for a nuanced understanding of outbreak potential, differentiating between the probability of any infection occurring and the expected severity of an outbreak that successfully establishes itself within the population. These calculations, derived from the Moyal distribution parameters, effectively capture the breadth of possible epidemic trajectories, ranging from rapid extinction to large-scale, sustained transmission.

Decomposing the Epidemic Curve: Spectral Decomposition and Validation

Spectral Decomposition is a novel technique for analyzing epidemic curves by representing them as a sum of individual waves. This is achieved through the application of the Moyal Probability Density Function (PDF), which allows for the identification and characterization of distinct transmission dynamics within a complex outbreak. The method effectively disaggregates an observed epidemic curve into its constituent parts, each potentially attributable to a specific viral variant, a shift in public health interventions, or a change in population behavior. By decomposing the curve in this manner, the technique facilitates a more granular understanding of outbreak drivers and enables improved monitoring of transmission patterns over time.

The Spectral Decomposition technique addresses the ‘Long Tail Effect’ – persistent low-level transmission characteristic of many modern outbreaks – by explicitly modeling heterogeneity in infectiousness. Traditional epidemic models often assume a homogenous infection rate, failing to account for the variance in transmission potential across a population. This method incorporates a distribution of infectiousness, acknowledging that some individuals contribute disproportionately to disease spread while others are less likely to transmit. By integrating this heterogeneity, the model avoids premature decay of the epidemic curve and accurately reflects the sustained transmission observed in the ‘long tail’, as opposed to predicting a rapid return to baseline incidence.

Model validation against historical SARS and MERS outbreaks confirmed its capacity to reproduce critical outbreak characteristics. Specifically, the Spectral Decomposition technique accurately captured ‘Dragon King events’ – instances of extreme superspreading – and ‘hollow shoulder’ effects, which represent a delayed increase in case numbers following initial introductions. Notably, the model successfully preserved the probability of the exceptionally large superspreading event observed during the MERS outbreak, replicating the estimated 80 infections originating from a single index case, demonstrating its sensitivity to heterogeneous transmission patterns.

Analysis of the German COVID-19 dataset (2020-2023) using the Spectral Decomposition technique identified nine distinct waves of infection. This demonstrates the model’s capacity to resolve overlapping epidemic dynamics and differentiate between successive outbreaks. The identification of these waves was achieved through decomposition of the overall epidemic curve into constituent components, each representing a period of sustained transmission potentially driven by viral evolution or changes in public health interventions. This capability supports improved epidemiological surveillance and forecasting by providing a granular view of pandemic progression beyond simple cumulative case counts.

Implications for Intervention and the Path Forward

The severity of an outbreak is not solely determined by the infectiousness of a pathogen, but crucially by the interplay between how much virus an infected individual sheds and the density of the surrounding population – a phenomenon termed ‘Collision Dynamics’. This model demonstrates that high viral shedding, when combined with crowded environments, dramatically increases the probability of transmission, exceeding what would be predicted by either factor in isolation. Essentially, the more infectious particles present, and the more people in close proximity, the greater the chance of a successful infection. Understanding this dynamic is paramount for accurately forecasting outbreak trajectories and implementing targeted interventions, such as prioritizing ventilation improvements or density reduction strategies in high-risk settings, to effectively disrupt transmission chains.

The study reveals that the rate at which an infected individual generates infectious units, termed the ‘Quanta Generation Rate’, significantly influences outbreak dynamics and presents a key target for intervention. This parameter, representing the amount of virus shed and its potential to initiate new infections, demonstrates a substantial variation across individuals – meaning some people contribute disproportionately to transmission. Interventions focused on identifying and mitigating transmission from these ‘super-shedders’ – perhaps through prioritized testing, isolation, or targeted ventilation strategies – could prove highly effective in curbing outbreaks. Understanding and quantifying this rate allows for a shift from broad, population-level interventions to more precise, risk-based approaches, optimizing resource allocation and maximizing public health impact. The model suggests that even modest reductions in the Quanta Generation Rate, achieved through measures like mask-wearing or improved hygiene, can lead to substantial decreases in overall transmission rates.

The developed framework offers a foundation for designing more effective public health interventions by acknowledging that disease transmission isn’t a predictable process, but rather one influenced by chance – a stochastic element. Crucially, it also recognizes that not everyone infected is equally likely to spread the disease; individuals exhibit a marked heterogeneity in their infectious potential. This is powerfully demonstrated by the model’s ability to accurately reflect the reality of the 2003 SARS outbreak, where approximately 73% of cases ultimately failed to produce any further secondary infections. This insight underscores the potential for targeted strategies focusing on super-spreading events and identifying individuals who pose the greatest risk of transmission, moving beyond broad-based interventions and allowing for more efficient resource allocation.

Advancing pandemic preparedness necessitates a synthesis of theoretical modeling with robust, data-driven analysis. Future investigations should prioritize integrating this framework – which accounts for stochastic transmission and individual infectiousness – with real-time epidemiological data and forecasting techniques. Such an approach promises to refine predictive accuracy, moving beyond broad estimations toward nuanced, localized projections of outbreak severity and spread. Crucially, this integration will facilitate optimized resource allocation, enabling public health officials to proactively deploy interventions – such as targeted testing, vaccination campaigns, and social distancing measures – to the populations and locations where they will have the greatest impact, ultimately bolstering resilience against future pandemics.

The pursuit of predictive modeling, as demonstrated in the analysis of epidemic dynamics, reveals a fundamental truth: the map is not the territory. This study, employing the Moyal distribution to reconcile microscopic and macroscopic views of outbreaks, echoes a sentiment articulated by Marcus Aurelius: “You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” The algorithm, however sophisticated, remains a representation, susceptible to the biases and limitations inherent in its construction. Scalability without acknowledging the ethical implications of the underlying assumptions-the very ‘social friction’ shaping transmission-risks acceleration toward chaos. The Moyal distribution, in attempting to capture epidemic volatility, highlights that understanding the system requires acknowledging the inherent unpredictability and the values encoded within the model itself.

Beyond the Curve

The application of the Moyal distribution to epidemic modeling, while a mathematically elegant advance, subtly shifts the focus from mitigating harm to refining prediction. The pursuit of ever-finer statistical descriptions of pandemic waves risks becoming an end in itself. One must ask: what exactly is being optimized? Is it merely the capacity to anticipate superspreading events, or a genuine reduction in societal vulnerability? The model’s incorporation of ‘social friction’ is a notable step, but further work must interrogate the very structures that create that friction – the inequalities, the precarity, the systemic failures – rather than simply treating them as parameters in a distribution.

Future research should not solely concentrate on improving the fit between model and data. Instead, it should grapple with the ethical implications of increasingly sophisticated forecasting tools. Algorithmic bias, inherent in any encoding of complex systems, is a mirror reflecting existing societal biases. Transparency in model construction and data sourcing is not merely desirable; it is the minimum viable morality.

Ultimately, the value of this framework-and indeed, of all quantitative epidemiology-lies not in its ability to predict the inevitable, but in its potential to inform interventions that alter the underlying conditions. The true challenge is not to map the contours of disaster, but to dismantle the systems that make it so predictable.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.08101.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

- ‘Stranger Things’ Creators Break Down Why Finale Had No Demogorgons

2026-02-11 00:09