Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach uses artificial intelligence to rapidly deploy repair crews following severe weather events, minimizing outage times.

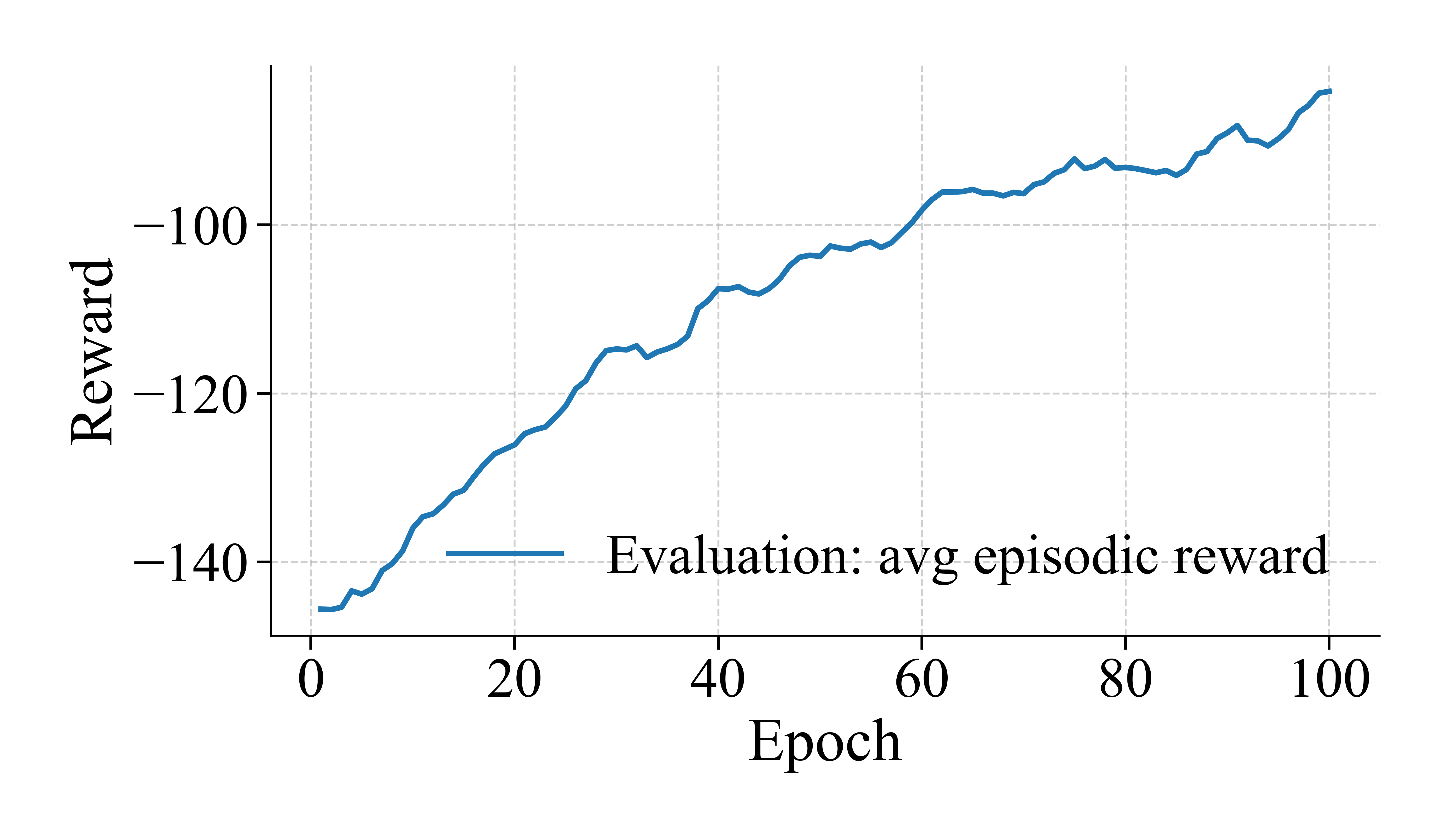

This paper presents a deep reinforcement learning dispatcher for post-storm power system restoration, achieving performance comparable to mixed-integer optimization with significantly reduced computation time.

Responding to increasingly frequent and severe weather events presents a critical challenge for power grid operators, demanding rapid and adaptive restoration strategies. This is addressed in ‘Event-Driven Deep RL Dispatcher for Post-Storm Distribution System Restoration’, which introduces a deep reinforcement learning approach to real-time crew dispatch following storm damage. The proposed method achieves performance comparable to complex optimization techniques while significantly reducing computational burden through lightweight, event-driven simulation. Could this framework enable more resilient and proactively managed power grids in the face of escalating climate risks?

Understanding the Flaws in Our Grid: Why Realistic Modeling Matters

Following a major disruptive event, such as a hurricane or widespread flood, the ability to accurately assess damage is paramount to swiftly and effectively deploying resources. Detailed post-storm damage modeling moves beyond simple estimations of affected areas; it pinpoints critical infrastructure failures – downed power lines, compromised transportation networks, and breached water systems – allowing for targeted assistance. This precision is not merely about efficiency; it directly impacts the speed of grid restoration, the delivery of emergency services, and ultimately, the preservation of life and property. Without realistic damage assessments, resource allocation becomes a guessing game, potentially diverting aid from areas of greatest need and prolonging recovery times, highlighting the critical need for advanced modeling capabilities in disaster preparedness and response.

Conventional damage assessment techniques frequently fall short when predicting the extent of widespread destruction because they tend to treat damage as randomly distributed, ignoring the inherent spatial relationships observed in real-world events. These methods often assume independence between failures – that damage to one component of a power grid, for example, doesn’t increase the likelihood of failure in nearby components. However, natural disasters rarely act in isolation; wind patterns, flooding, and debris fields create correlated damage, where adjacent infrastructure is likely to experience similar impacts. This simplification overlooks critical cascading effects, leading to underestimates of total damage and hindering the development of effective restoration strategies. Consequently, simulations built on these assumptions may fail to accurately represent the complex interplay of failures and the true extent of a disaster’s impact on interconnected systems.

The complex interplay of failures following a major weather event demands a simulation environment capable of modeling cascading effects with high fidelity. Current infrastructure modeling often treats components in isolation, failing to account for how damage to one element-a substation, for example-can propagate through the network, triggering further outages and creating widespread disruption. A truly robust simulation doesn’t simply assess direct damage; it traces the domino effect of component failures, accounting for factors like overloaded circuits, reduced capacity, and the geographic interdependencies within the power grid. This requires integrating detailed physical models of infrastructure with probabilistic assessments of component vulnerability and realistic representations of environmental stressors, ultimately allowing for proactive identification of critical weaknesses and the development of more resilient restoration strategies. Such environments move beyond static risk assessment to provide a dynamic, predictive capability essential for modern grid management.

Simulating the Unpredictable: An Event-Driven Approach to Grid Failure

An Event-Driven Simulator (EDS) is employed to model post-storm grid failures due to its efficiency in handling asynchronous events and time-dependent system responses. Unlike time-stepping simulations that evaluate system state at fixed intervals, the EDS advances simulation time only when events occur – such as component failures or operator actions. This approach significantly reduces computational burden when modeling rare events like cascading failures, which are triggered by a sequence of component failures following an initiating event like a storm. The simulator tracks the state of each grid element (lines, transformers, buses) and propagates failures based on predefined contingency rules and network topology, allowing for the observation of cascading failure patterns and the evaluation of grid resilience under various storm scenarios.

Damage assessment within the simulation framework utilizes Lognormal Fragility curves to quantify the probability of component failure as a function of hazard intensity. These curves are parameterized using data derived from both Hurricane Wind Field and Flood Depth Field analyses. Specifically, the wind speed and flood depth at each simulated grid location are used as inputs to the fragility curves, which are defined for key grid components such as poles, wires, and transformers. The resulting curves provide a probability of failure for each component, allowing the simulation to stochastically determine which components are damaged based on the observed hazard levels at their locations. The Lognormal distribution is employed due to its ability to model the positive skewness typically observed in failure data and its mathematical tractability for probabilistic calculations.

Spatial correlation of damage, critical for realistic grid modeling, is implemented using a Gaussian Copula function. This statistical technique allows for the modeling of dependencies between damage states at geographically distinct locations; rather than assuming independent failures, the Copula defines a joint distribution based on the marginal distributions of damage at each node. The parameters of the Copula, specifically the correlation coefficient ρ, determine the strength of this spatial dependency – higher values indicate stronger correlation and a tendency for geographically proximate nodes to experience similar damage levels. By incorporating this dependency, the simulation accurately reflects the observed patterns of cascading failures where damage in one area increases the probability of damage in neighboring areas, improving the fidelity of the overall grid resilience assessment.

The modeling of confirmed outages post-event employs a Nonhomogeneous Poisson Process (NHPP) to represent the stochastic arrival of outage reports. Unlike a standard Poisson Process with a constant rate, the NHPP allows the outage reporting rate, \lambda(t), to vary over time, t. This time-dependent rate is crucial as initial outages often trigger a surge in reported failures due to cascading effects and increased system stress. The \lambda(t) function is parameterized based on event-specific data and system characteristics, allowing the model to reflect the observed increase in outage reports immediately following the initial impact, and the subsequent decrease as the most vulnerable components fail and remaining infrastructure stabilizes. This approach more accurately captures the dynamic nature of grid failures compared to assuming a constant outage reporting rate.

Putting Theory to the Test: Validating Dispatch Heuristics Against Real-World Systems

Performance benchmarking of crew dispatch heuristics was conducted utilizing the widely adopted IEEE 13-Bus System and the larger IEEE 123-Bus System distribution test feeders. These systems represent standard configurations for distribution network analysis, allowing for comparative evaluation across different heuristic approaches. The IEEE 13-Bus System, a smaller network, provides a computationally efficient environment for initial testing and validation, while the IEEE 123-Bus System offers a more complex and representative scenario for assessing scalability and performance under increased system load. Both feeders were utilized to simulate post-storm outage scenarios and quantify the effectiveness of each heuristic in restoring service to affected customers.

The Marginal Value-Per-Time Heuristic functions as a comparative benchmark by assigning priority to outage restoration based on the ratio of load impacted to estimated restoration time. This approach prioritizes outages affecting the largest number of customers with the shortest anticipated repair duration, effectively maximizing the immediate reduction in unserved load. The heuristic calculates a value for each outage representing the potential load restored per unit of time, and dispatches crews accordingly. While straightforward, this method serves as a foundational performance measure against which more complex heuristics – incorporating factors like travel time or crew availability – are evaluated to determine if their added complexity yields demonstrable improvements in system restoration performance.

The Travel-Aware Heuristic addresses real-world limitations of crew dispatch by incorporating travel time as a primary optimization factor. Unlike heuristics solely focused on outage severity, this approach calculates estimated travel times for each crew to reach affected locations, factoring in network topology and road accessibility. This calculation influences dispatch priority, ensuring that crews are assigned to outages not only based on impact, but also on their proximity and feasible travel routes. The intent is to reduce overall restoration time by minimizing unproductive travel and maximizing crew utilization, acknowledging that minimizing travel time is crucial for efficient post-event response.

Performance evaluations on the IEEE 13-Bus System demonstrate a significant improvement in outage response using the developed heuristics compared to the Marginal Value-Per-Time baseline. Specifically, total Energy Not Supplied (ENS) was reduced by 44%, decreasing from 44 MWh to 32 MWh. Furthermore, the time required to restore critical loads was decreased by 37%, improving from 135 minutes to 85 minutes. These results indicate a substantial enhancement in system reliability and a faster return to normal operating conditions following a disruptive event.

Evaluation of the crew dispatch heuristics was performed using the Event-Driven Simulator, a software environment designed to model power system behavior following disruptive events. This simulation platform allows for the injection of faults representing storm damage, enabling the assessment of heuristic performance under realistic conditions. Key performance indicators, including Energy Not Supplied (ENS) and critical load restoration time, are quantified through repeated simulations with varying fault scenarios. The simulator accounts for dynamic system changes, such as load shedding and sectionalizing, providing a detailed and reproducible environment for comparative analysis of dispatch strategies. This approach ensures that observed improvements in ENS and restoration time are demonstrably linked to the implemented heuristics and not to arbitrary simulation parameters.

Evaluation on the 123-bus test system demonstrated a substantial performance improvement using the proposed dispatch heuristics. Specifically, the total Energy Not Supplied (ENS) was reduced by 38%, decreasing from 58 MWh under the baseline Marginal Value-Per-Time Heuristic to 36 MWh. Furthermore, critical load restoration time was decreased by 31%, improving from 210 minutes to 145 minutes. These results indicate a significant enhancement in grid resilience and faster service recovery capabilities when employing the developed dispatch strategies on larger distribution systems.

The pursuit of efficient crew dispatch, as detailed in this work, highlights a fundamental truth about modeled systems: the human element isn’t an inconvenience to be smoothed over, but the very source of predictable patterns. The study demonstrates a deep reinforcement learning approach achieving comparable results to optimization – a seemingly rational benchmark – but with speed. This isn’t about finding the optimal solution, but approximating a useful one quickly, acknowledging the chaotic reality of post-storm restoration. As René Descartes observed, “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but it is necessary to a clear understanding.” The imperfections in the learned dispatch policy, much like the doubts that drive inquiry, reveal the limitations of any model and, consequently, the deeply ingrained habits and fears that shape real-world responses to crisis.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This work, applying deep reinforcement learning to the logistical puzzle of post-storm power restoration, feels less like a triumph of artificial intelligence and more like a particularly elegant codification of human impatience. The speed advantage over optimization methods isn’t about discovering new efficiencies; it’s about satisfying the demand for immediate action, even if that action isn’t demonstrably better. Economics doesn’t describe the world – it describes people’s need to control it. The system offers a faster response, which is, ultimately, a psychological benefit disguised as a technical one.

The true limitations aren’t computational, but perceptual. The simulations, however detailed, are still abstractions, built on assumptions about storm patterns, crew availability, and the very definition of “restoration.” Real-world events are messier, infused with unpredictable human factors – a crew chief’s intuition, a homeowner’s desperation, the simple chaos of a damaged landscape. The next step isn’t more sophisticated algorithms, but a better understanding of how these messy realities distort the neatness of the model.

Perhaps the most pressing question is not whether the system can restore power efficiently, but whether it can convincingly appear to do so. We aren’t rational – we’re just afraid of being random. The illusion of control, delivered swiftly, may ultimately prove more valuable than genuine optimization. Future work should address how to quantify, and perhaps even exploit, this inherent human bias.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10044.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- Gold Rate Forecast

- A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Season 1 Finale Song: ‘Sixteen Tons’ Explained

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- Beyond Linear Predictions: A New Simulator for Dynamic Networks

- All Songs in Helluva Boss Season 2 Soundtrack Listed

2026-01-18 03:00