Excerpt from ‘A Place Both Wonderful and Strange: The Extraordinary Untold History of Twin Peaks’

From the very beginning, Twin Peaks faced a challenge: viewers were obsessed with finding out who killed Laura Palmer, but the creators, David Lynch and Mark Frost, were reluctant to reveal the killer. When they finally agreed to share the answer, the network saw it as a success. The episode drew a massive 17 million viewers – the highest the show had ever reached since its second episode.

With the mystery of Laura Palmer’s murder solved, the show faced a bigger challenge: figuring out what Twin Peaks was actually about. Even Bob Iger, then a network executive, now admits he might have pushed for answers too soon. He’s said he initially thought David Lynch was deliberately confusing viewers, but now believes demanding to know who killed Laura Palmer actually disrupted the show’s storyline. Mark Frost agrees, stating they lost a lot of momentum because of it. David Lynch was even more direct, saying that demand “killed Twin Peaks,” effectively ending it.

The core issue was that Twin Peaks hadn’t reached its conclusion. It was halfway through its second season, with at least 13 more episodes planned to continue the story. Mark Frost explains that with a 22-episode network television season, the demands of production leave you with little choice but to keep going. Scott Frost adds that the show’s direction wasn’t fully mapped out, comparing production to parachuting – they had a plan (the parachute), but it wasn’t quite in place yet.

The solution to Laura Palmer’s murder wasn’t a neat ending, but rather a pause, hinting that the evil BOB still exists and will search for a new person to control. Once the main mystery was solved, the show’s creators felt free to explore new and unexpected directions for Twin Peaks. Writer Robert Engels explains they became skilled at resolving plot points, which made them confident in taking risks. Harley Peyton adds that this freedom was a key part of the show’s appeal – they felt they could try anything. While this sometimes led to strange or unsuccessful storylines, it also often took them in brilliant directions. Peyton believes that these missteps were a natural part of creating something unique under challenging circumstances.

Following Leland’s death, Twin Peaks felt strained as it created a weak new reason for Agent Cooper to stay in town. Cooper faced suspension from the FBI – rightly for his unauthorized operation at One Eyed Jack’s, and wrongly accused of stealing cocaine. He was forced to give up his badge and gun. The show had already hinted at Cooper becoming more connected to Twin Peaks, and it seemed unlikely he’d permanently leave the Double R Diner and its coffee and pie. However, temporarily removing Cooper’s FBI status significantly changed the show’s core structure, creating problems that were hard to fix. A lot of effort had gone into establishing the show’s unique atmosphere, and this change disrupted it. As editor-director Duwayne Dunham puts it, the show’s problems began when Cooper traded his suit for a lumberjack’s flannel.

Twin Peaks was known for mixing dark and funny moments, but maintaining that balance became increasingly difficult. According to Peyton, a mistake they might have made was leaning too heavily into comedy. Writers often need to consider whether they’re writing for their own amusement or for the audience, and in this case, they were definitely enjoying themselves, hoping the audience would too.

A look back at Twin Peaks‘ second season wouldn’t be complete without mentioning some of its more unusual plots. Remember Nadine Hurley, who woke from a coma with super strength but the emotional maturity of a teenager? Creator Peyton explains he added that because he was a comic book fan and thought it would be funny. Then there was Lana Milford, who charmed two elderly brothers and inexplicably made every other man in town – even Cooper – act foolishly. Peyton admits that storyline was intended to have a supernatural explanation, but it never materialized. And who could forget Ben Horne’s bizarre attempt to rewrite history, convinced he was Robert E. Lee? Writer Scott Frost reveals that idea was directly inspired by Ken Burns’ The Civil War miniseries, and likely wouldn’t have happened without it.

Peyton recalls one moment in Twin Peaks as particularly regrettable: James Hurley’s short, separate storyline involving a classic film noir plot with the character Evelyn Marsh. Peyton explains that James’s actor had a natural quality that made him ideal for that type of story, which is what inspired the detour.

James’s romantic life has become incredibly dramatic and complicated, much like the classic novel Peyton Place. James Marshall, the actor who plays James, feels the storyline would have been stronger if James had stayed with Donna. He believes their connection became clear after Laura’s death, and they could have supported each other through their grief. Instead, the story introduced Evelyn Marsh.

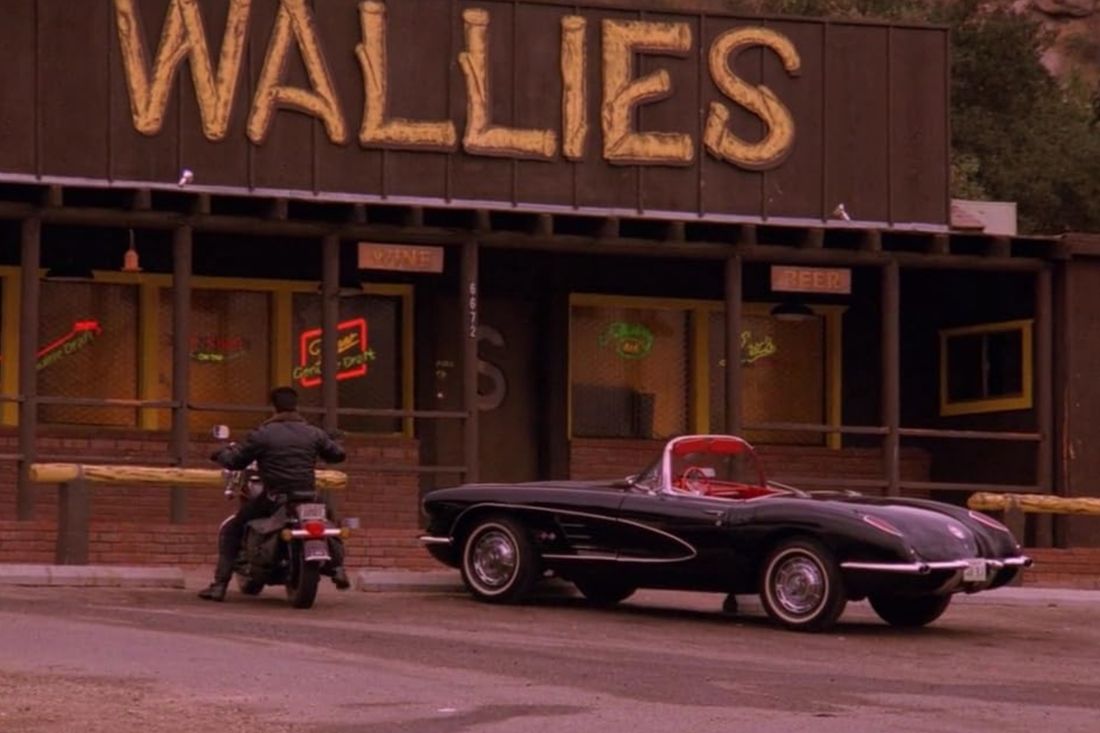

A strange side story, separate from the main events of Twin Peaks, follows James as he rides his motorcycle alone after Maddy’s death. He unexpectedly finds himself in a situation straight out of a classic crime novel. The show had hinted at this style of storytelling before, referencing author James M. Cain with a character named after the protagonist of Cain’s famous novel, Double Indemnity. This subplot, clearly inspired by Cain, unfolds over five episodes. A married woman named Marsh picks up James at a bar, employs him as a mechanic, has an affair with him, and then tries to set him up for her husband’s murder. However, she later changes her mind and lets him go.

The story felt very formulaic, like a classic film noir, and the people making the TV show were as skeptical of the plot as the viewers. Director Lena Dunham, who worked on an episode featuring the Evelyn Marsh storyline, felt the character didn’t fit the show’s tone. She compares Evelyn to a character from a soap opera like Dynasty and admits she wishes she’d handled the subplot better, feeling it didn’t align with James’s character and motivations – he was part of the Bookhouse Boys. Actor Marshall agrees, noting that many experienced performers on the show were actively pushing for changes to their roles, something he was hesitant to do himself.

Lara Flynn Boyle felt lost during filming, constantly unsure of what was happening with her character. She admits to repeatedly calling David Lynch, worried the show was going downhill, which he eventually grew tired of. Sherilyn Fenn recalls a specific incident with a costumer who seemed to misunderstand the show’s artistic vision, bringing in twenty hula skirts and leading Fenn to question if everyone realized Twin Peaks wasn’t just about being bizarre for the sake of it – it always had a deeper purpose.

Lena Dunham explains that the show sometimes felt bizarre simply for the sake of being strange. However, she believes this isn’t a fair assessment of David Lynch’s work. According to Dunham, Lynch’s work always has a clear intention and reason behind it, which is why he’s able to pull off even the most unusual elements effectively.

Things hit a low point with “Episode 21,” which was directed by Uli Edel – the first and only episode he directed. Edel was known for his work on the critically praised, dark drama Last Exit to Brooklyn, and was considered a promising director. However, his harsh directing style didn’t go over well with the cast, who felt they had a good understanding of their roles by that point. Michael Horse recalls Edel telling him, “You’re just furniture to me, man. Just go where I tell you.” Horse then asked the crew if Edel was a good director, and they assured him he was. Horse then confronted Edel, saying, “Hey, you can say that to me, but if this isn’t outstanding work, I’ll come to your house and kick your ass.”

Sheryl Lee’s character, Horse, having issues with the character of Edel mirrored the feeling among the cast that the new version of Twin Peaks wasn’t being handled well while David Lynch and Mark Frost were occupied with other projects. According to Sheryl Lee, claims that Lynch and Frost were closely overseeing every detail weren’t true. She explains that working directly with David Lynch resulted in a very different show, and she believes the change in leadership negatively impacted the series. “No matter how talented someone is, they can’t replicate David Lynch’s unique style,” she says.

While many fans assume David Lynch’s absence caused the issues in Twin Peaks Season 2, it was actually Mark Frost who was away from the show during that time. Lynch directed Wild at Heart during part of Season 1, and Frost took time off during Season 2 to direct the James Spader thriller Storyville. According to producer Peyton, Frost’s absence created difficulties, particularly impacting his working relationship with Lynch.

Peyton and Engels were already known as two of the most dependable writers on Twin Peaks, and by this point, they had also taken on producer roles and some of the responsibilities that today would be considered “showrunning.” When Frost went to New Orleans to film Storyville, Peyton was left in charge. He explains, “We already knew what each episode would be, and Mark was checking in with me daily, so it wasn’t like I needed to gather a writers’ room to figure things out.” However, one night, late at night, director Todd Holland called, panicked after receiving a lot of script notes from David Lynch that would affect the next day’s filming. Peyton, already a bit frustrated, told him, “Just ignore David’s notes. He shouldn’t be calling you with changes this late at night. Just film what you planned and don’t worry about it.” He felt he’d handled the situation and done his job.

The next day, David called and unleashed a furious ten-minute tirade at me. It was a long time to be yelled at, and his anger was intense – I’d rarely seen him lose his temper like that. He was screaming, demanding to know what I thought I was doing and how I dared. The call ended badly, and it effectively ended our relationship.

Creative clashes among the show’s writers were made even more difficult by the actors, who actively tried to influence the direction of their characters’ storylines. Marshall explains, “Things were getting politically charged, and I decided it was best to stay out of it.” He adds that other actors were also pushing for changes, and he didn’t want to get caught in the middle.

One of the biggest changes was the removal of the developing romantic connection between Cooper and Audrey Horne, a storyline that had been hinted at since the first season. Tina Rathborne, who directed a notably suggestive scene between them, explained that Audrey’s attempts to attract Cooper were meant to show two sides of his personality: his innocence and a willingness to explore his darker impulses. She felt it demonstrated his capacity for both temptation and maintaining his moral compass.

I was so captivated by Cooper in the first season! It was sweet how, even when Audrey showed up at his hotel room in a vulnerable state, he responded with kindness and a genuine desire to be a friend. Though, you could really feel the spark between Kyle MacLachlan and Sherilyn Fenn – the writers clearly couldn’t resist bringing Cooper and Audrey back together. Audrey’s willingness to go undercover at One Eyed Jack’s just to help him, “her special agent,” was amazing, and Cooper risked everything to save her. I even remember a moment where Audrey felt a little insecure about another woman in Cooper’s life, Denise, and playfully – but definitely purposefully – kissed him to let him know she wasn’t going anywhere!

The writers clearly intended to develop a romantic connection between Cooper and Audrey, despite Kyle MacLachlan’s reservations. Sheryl Fenn recalls David Lynch asking her if she had feelings for Kyle, to which she responded with laughter, stating there was no personal chemistry between them. However, she acknowledged a strong connection between their characters. According to Peyton, the plan was to explore a relationship between Audrey and Cooper, but it was ultimately abandoned because MacLachlan wasn’t interested in pursuing it.

The commonly accepted explanation for why Kyle MacLachlan didn’t like a particular storyline is that he felt his character, Cooper, wouldn’t be involved with a high school student. This makes sense, as Cooper previously turned down Audrey for similar reasons. However, personal relationships likely also influenced his decision. At the time, MacLachlan was dating Lara Flynn Boyle, and some believed her insistence on a dramatic change to Donna’s character in season two was motivated by jealousy over Sheryl Fenn receiving more praise for her portrayal.

Peyton recalls a conversation with Mark Frost where Frost expressed strong opposition to a particular idea. He felt it would disrupt the carefully laid plans for their second season and draw a firm line against it. Kyle and David then met privately with Frost, and Peyton remembers a long wait before Kyle emerged to announce they wouldn’t be moving forward. The reason, Peyton learned, was David’s willingness to prioritize the actors’ preferences. Over time, Peyton realized David would go to great lengths for the cast, and in return, they were incredibly loyal to him.

Regardless of the reasons behind it, even those who initially disagreed with MacLachlan’s explanation now admit it was probably for the best that the romantic storyline between Cooper and Audrey didn’t develop further. According to Peyton, current standards would likely prevent such a relationship due to the power imbalance and age difference, echoing concerns Kyle raised at the time. While some believe Lara Flynn Boyle was the reason, the true motivation remains unclear. Peyton points out that Cooper eventually found a love interest who was closer in age to Audrey, and surprisingly, she had a background as a nun.

Cooper had a secret lover, Annie Blackburn (played by Heather Graham), who was Norma Jennings’ half-sister. She was introduced to the show to explore the romantic tension that was originally intended for the Cooper-Audrey storyline, and Graham understood the role she was taking on. Interestingly, Graham had some prior connection to David Lynch’s work, having appeared with Benicio del Toro in a Calvin Klein commercial he directed. However, portraying a character who could immediately captivate Agent Cooper presented a new challenge. Graham met with Lynch at his home to discuss Annie, but not before he showed her one of his unusual projects: an art installation involving meat and ants.

Graham remembers David Lynch portraying Annie as incredibly delicate, comparing her to a high-performance sports car like a Ferrari – beautiful and impressive, but easily disrupted if anything went wrong. However, Mark Frost offered a more straightforward assessment, admitting that Annie was, at least originally, a fairly typical ‘damsel in distress’ character, and not much beyond that.

Audrey found a new romantic interest, but not before the show hinted at a possible connection with Bobby, who was briefly considered as Ben Horne’s assistant. Dana Ashbrook, who played Bobby, wasn’t sure if the Audrey-Bobby storyline was ever fully intended. He believed it was going to happen, but it seemed like plans changed frequently during production. Ultimately, Bobby remained loyal to Shelly – though Gordon Cole unexpectedly kissed her – and Audrey ended up with John Justice Wheeler, a charming pilot and businessman played by Billy Zane. Mark Frost revealed that Harley Peyton came up with the idea for Wheeler, suggesting him as the perfect ‘singing cowboy’ to win Audrey’s heart.

Okay, so this is a weird but sweet part of the show. Wheeler, trying really hard to win Audrey over, goes full cowboy – hat, picnic, the whole nine yards. He even serenades her with this old cowboy song, “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie.” Honestly, it’s a bit much! Apparently, it didn’t make a great first impression on actress Dana Ashbrook, who played Audrey. She said he asked her, bright and early one morning, if he could just lean in and kiss her – which understandably made her a little uncomfortable! But, despite that awkward start, his over-the-top efforts did work. The script actually notes that Audrey genuinely seems to forget all about Cooper and is completely reassured when she tells Wheeler she’s not interested in anyone else. It’s a funny little scene, and it shows how desperate Wheeler is to win her over.

As Cooper and Audrey pursued their own romances, and other characters dealt with individual storylines, Twin Peaks needed a central villain and a major event to bring everything back together. Windom Earle, Cooper’s vengeful former partner who escaped from custody, served that purpose in the second half of season two. Initially, the conflict between Cooper and Earle wasn’t meant to be a long-running plot. However, after the show hired Kenneth Welsh to play Earle – a friend of co-writer Larry Engels – the character became much more prominent. Engels convinced the producers to cast Welsh, and they were so impressed with his performance that Earle’s storyline expanded significantly, becoming the show’s main focus after the mystery of Laura’s murder was solved.

Having escaped from a mental hospital and followed Cooper to Twin Peaks, Earle challenges him to a disturbing game of chess. With each piece Earle captures, a corresponding person is murdered – often someone seemingly random and unconnected to the main story, like a homeless man if he loses a pawn.

Once Cooper understands Earle’s plan, he shifts his focus from winning to simply safeguarding what he has left. It seems obvious he should prioritize protecting his queen, particularly because he’s falling for Annie, who is vulnerable and naive, making her a clear target. You’d also expect him to recognize the danger when a Giant physically appears and warns him against letting Annie enter the Miss Twin Peaks pageant. However, Cooper’s judgment seems clouded by love; he’d been flirting with Annie at the Double R just a short time before and completely missed the obvious presence of Windom Earle.

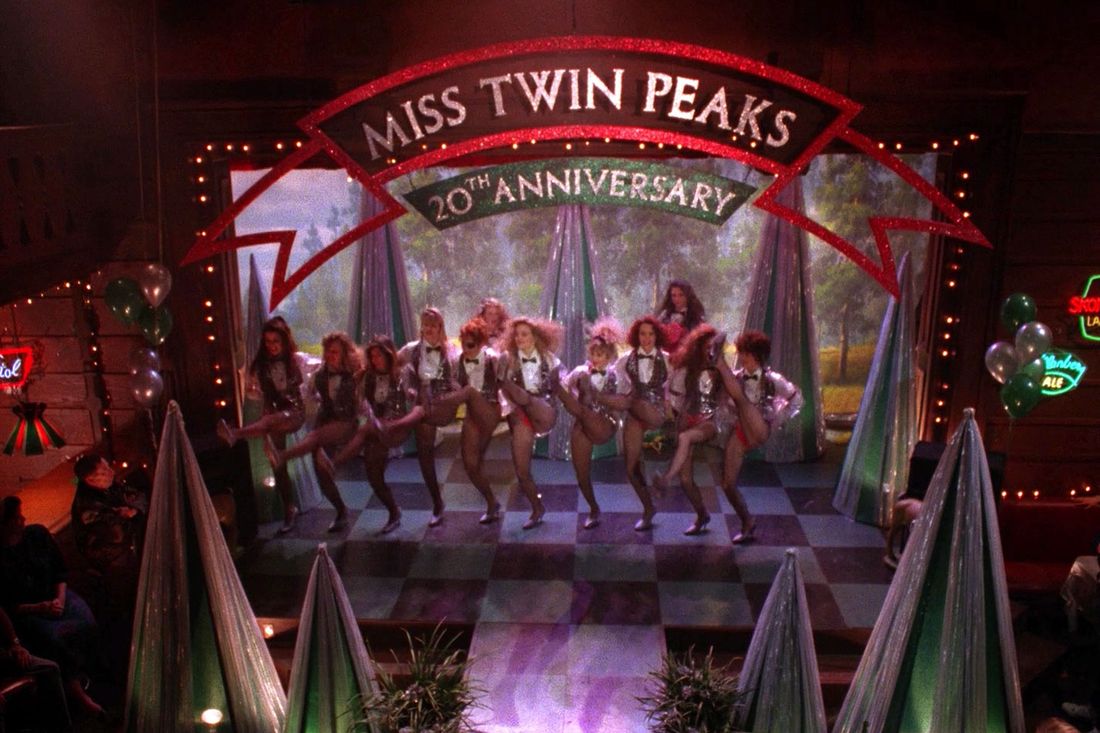

The many storylines in Twin Peaks come together in the second-to-last episode, which also marks the end of the show’s lighter, more comedic approach that had become prominent in the first season. The Miss Twin Peaks pageant was created, in part, to reunite the characters who had begun to drift apart: Donna Hayward, Shelly Johnson, Lucy Moran, Nadine Hurley, Lana Milford, and Annie Blackburn all compete, while Norma Jennings, Doc Hayward, Pete Martell, and Dick Tremayne serve as judges. Interestingly, Audrey is largely missing from the competition, despite being a target of Windom Earle just a few episodes prior. As Sherilyn Fenn recalls, she immediately told David Lynch she wouldn’t participate. “There was no way I was going to parade around in a bathing suit on a catwalk,” she said.

Despite some silliness, the lighthearted moments are a relief before Twin Peaks descends into its final, dark turn. There’s a unique performance by Lana Milford, described as “contortionistic jazz exotica,” and Lucy Moran does a dance ending in a split, which worried viewers so much that Kimmy Robertson (the actress, who wasn’t actually pregnant) had to assure everyone she was unharmed. Then, when Annie Blackburn wins Miss Twin Peaks with a speech inspired by Chief Seattle, a leader of Washington State’s Suquamish and Duwamish tribes, Earle makes his move. He’s been hiding in plain sight at the pageant, disguised as the Log Lady, and now that a queen has been crowned, he’s ready to take her.

The season finale ended on a huge cliffhanger, but that wasn’t how it was originally intended to air. ABC’s broadcast schedule for Twin Peaks had become unpredictable, with long breaks in December and January, and the situation worsened when the Gulf War interrupted the show. After the bizarre cliffhanger of Episode 23 – which revealed Josie Packard as Cooper’s shooter and left her mysteriously trapped in a drawer pull – ABC put the show on hold. This upset fans, who launched a campaign called COOP (Citizens Opposed to the Offing of Peaks). They flooded ABC with hundreds of phone calls and thousands of letters and packages, some even including logs or doughnuts. David Lynch encouraged the effort during a February appearance on Late Night With David Letterman, where the host playfully shared Bob Iger’s mailing address. Letterman joked, “I love annoying these network weasels.”

ABC finally gave in, and Twin Peaks returned on Thursday, March 28th, offering a welcome break from the poor ratings of Saturday nights. However, this relief didn’t last long. On April 18, 1991, “Episode 27” aired – a strong episode that ended with the intriguing return of BOB from the Black Lodge. Unfortunately, viewers who were hooked by this cliffhanger had to wait almost two months, until June 10th, when the network unceremoniously aired the final two episodes back-to-back. While Twin Peaks hadn’t been officially cancelled, everyone connected with the show understood it was coming to an end. As Mark Frost admitted a month before the season finale, “the show is over” as a cultural phenomenon.

Scott Meslow’s book, From A Place Both Wonderful and Strange, which tells the complete, behind-the-scenes story of Twin Peaks, will be published by Running Press (an imprint of Hachette Book Group) on February 17, 2026.

View

Success! You’ll get an email when something you’ve saved goes on sale.

Yes

New! You can now save this product for later.

A Place Both Wonderful and Strange: The Extraordinary Untold History of Twin Peaks, by Scott Meslow

$30

$30

$30

at Amazon

$30

at Amazon

Read More

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- All Itzaland Animal Locations in Infinity Nikki

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Elder Scrolls 6 Has to Overcome an RPG Problem That Bethesda Has Made With Recent Games

- Super Animal Royale: All Mole Transportation Network Locations Guide

- Unlocking the Jaunty Bundle in Nightingale: What You Need to Know!

- BREAKING: Paramount Counters Netflix With $108B Hostile Takeover Bid for Warner Bros. Discovery

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Power Rangers’ New Reboot Can Finally Fix a 30-Year-Old Rita Repulsa Mistake

2026-02-21 00:59