Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research shows deep neural networks can accurately predict phytoplankton biomass-a key indicator of ocean health-by learning from physical ocean conditions.

A UNet-based auto-regressive model effectively emulates and forecasts global phytoplankton dynamics using physical predictors and time series analysis.

Accurately forecasting phytoplankton biomass-the foundation of marine ecosystems and a key driver of global biogeochemical cycles-remains a persistent challenge for ocean models. This is addressed in ‘Static and auto-regressive neural emulation of phytoplankton biomass dynamics from physical predictors in the global ocean’, which explores the application of deep learning to predict phytoplankton distribution using physical oceanographic variables. The authors demonstrate that a UNet-based, auto-regressive approach effectively reconstructs and forecasts phytoplankton biomass, capturing temporal variability with improved accuracy compared to traditional methods. Could these data-driven models provide crucial insights for monitoring ocean health and managing marine resources in a changing climate?

The Ocean’s Foundation: Understanding Phytoplankton Dynamics

Phytoplankton, microscopic plant-like organisms inhabiting the upper ocean, form the base of nearly all marine food webs and play an outsized role in regulating Earth’s climate. Their abundance, often measured by the concentration of Chlorophyll-a – the pigment they use for photosynthesis – directly influences the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. As phytoplankton thrive, they draw down atmospheric CO_2 through photosynthesis, effectively acting as a biological pump that sequesters carbon in the deep ocean. Monitoring Chlorophyll-a levels, therefore, provides a vital indicator of ocean health, revealing shifts in productivity, nutrient availability, and the overall efficiency of this crucial carbon cycle process. Changes in phytoplankton biomass can cascade through the food web, impacting fisheries and marine ecosystems, and also offer critical insights into the ocean’s role in mitigating climate change.

A significant challenge in understanding ocean health lies in the historical scarcity of long-term, consistent data regarding phytoplankton biomass, typically measured by Chlorophyll-a concentration. While phytoplankton forms the base of the marine food web and plays a vital role in global carbon cycling, continuous monitoring efforts have been limited, particularly before the advent of widespread satellite technology. This lack of baseline data makes it difficult to accurately discern natural variations in phytoplankton populations from those induced by anthropogenic factors like climate change and pollution. Consequently, assessing the true extent of ocean changes, predicting future trends, and implementing effective conservation strategies remains considerably hampered by this historical data gap, necessitating increased investment in sustained ocean observation systems.

Traditional methods of gauging phytoplankton biomass, primarily relying on satellite imagery and sparse in-situ measurements, frequently struggle to capture the full dynamism of ocean ecosystems. While satellites provide broad coverage, their resolution often blurs the fine-scale variations in Chlorophyll-a concentrations – critical for identifying blooms, upwelling events, and localized changes. Similarly, ship-based observations, though precise, are limited by their infrequent and geographically constrained nature, creating gaps in the data record. This combination of coarse spatial scales and infrequent temporal sampling hinders accurate modeling of primary productivity and carbon cycling, ultimately limiting the ability to distinguish between natural fluctuations and anthropogenic impacts on ocean health. Achieving a more comprehensive understanding necessitates integrating higher-resolution data from innovative sources, such as autonomous underwater vehicles and increased sensor deployment, to overcome these limitations and provide a truly robust analytical framework.

Building a Consistent View: The OC-CCI Observational Foundation

The Ocean Colour-Climate Change Initiative (OC-CCI) generates a continuous record of ocean color by integrating data from the SeaWiFS, MODIS, MERIS, and VIIRS satellite missions. These sensors, while differing in spectral characteristics and spatial resolution, are systematically cross-calibrated and merged to create a consistent dataset spanning multiple decades. This multi-sensor approach addresses limitations inherent in any single instrument, such as sensor drift or gaps in temporal coverage, and allows for a more robust and reliable assessment of long-term ocean color trends. The resulting data products provide estimates of key biogeochemical parameters, including Chlorophyll-a concentration, and are distributed in a standardized format for scientific analysis.

The OC-CCI’s utilization of multiple ocean color sensors – SeaWiFS, MODIS, MERIS, and VIIRS – enhances data reliability through cross-validation and gap-filling. Combining data from these independent sources mitigates individual sensor biases and reduces the impact of data loss due to cloud cover or instrument malfunction. This approach not only provides a more complete and accurate dataset but also improves the sensitivity to subtle variations in Chlorophyll-a concentrations, enabling the detection of trends that might be obscured when relying on a single sensor’s observations. The increased data density and reduced noise facilitate a more precise characterization of phytoplankton dynamics and allow for improved monitoring of long-term changes in ocean biology.

Effective utilization of the OC-CCI dataset for predictive oceanographic modeling necessitates advanced analytical techniques due to the inherent complexities of ocean dynamics. Chlorophyll-a concentrations, a key indicator derived from ocean color, exhibit substantial spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability across multiple scales – from daily blooms to interannual oscillations and long-term climate trends. Consequently, simple statistical models are often inadequate. Successful predictive modeling requires methods capable of capturing these complex spatiotemporal relationships, such as advanced time-series analysis, machine learning algorithms incorporating spatial covariates, or process-based models that simulate underlying biological and physical drivers. These methods must also account for data gaps, sensor biases, and the need for robust validation against independent observations.

Reconstructing Ocean Color: A Shift Towards Machine Learning

Linear Canonical Correlation Analysis (LCCA) has historically been employed to establish statistical relationships between Chlorophyll-a concentrations and key oceanographic variables. These variables include wind components – U10 representing eastward wind and V10 representing northward wind – alongside surface currents, quantified as eastward (U) and northward (V) components. Mean Dynamic Topography (MDT), a measure of sea surface height relative to a reference level, is also incorporated as a predictor in these models. LCCA identifies linear combinations of these predictors that maximize correlation with Chlorophyll-a, effectively modeling the influence of physical drivers on phytoplankton biomass. While foundational, these statistical methods are limited in their ability to capture non-linear relationships and complex interactions present in ocean ecosystems.

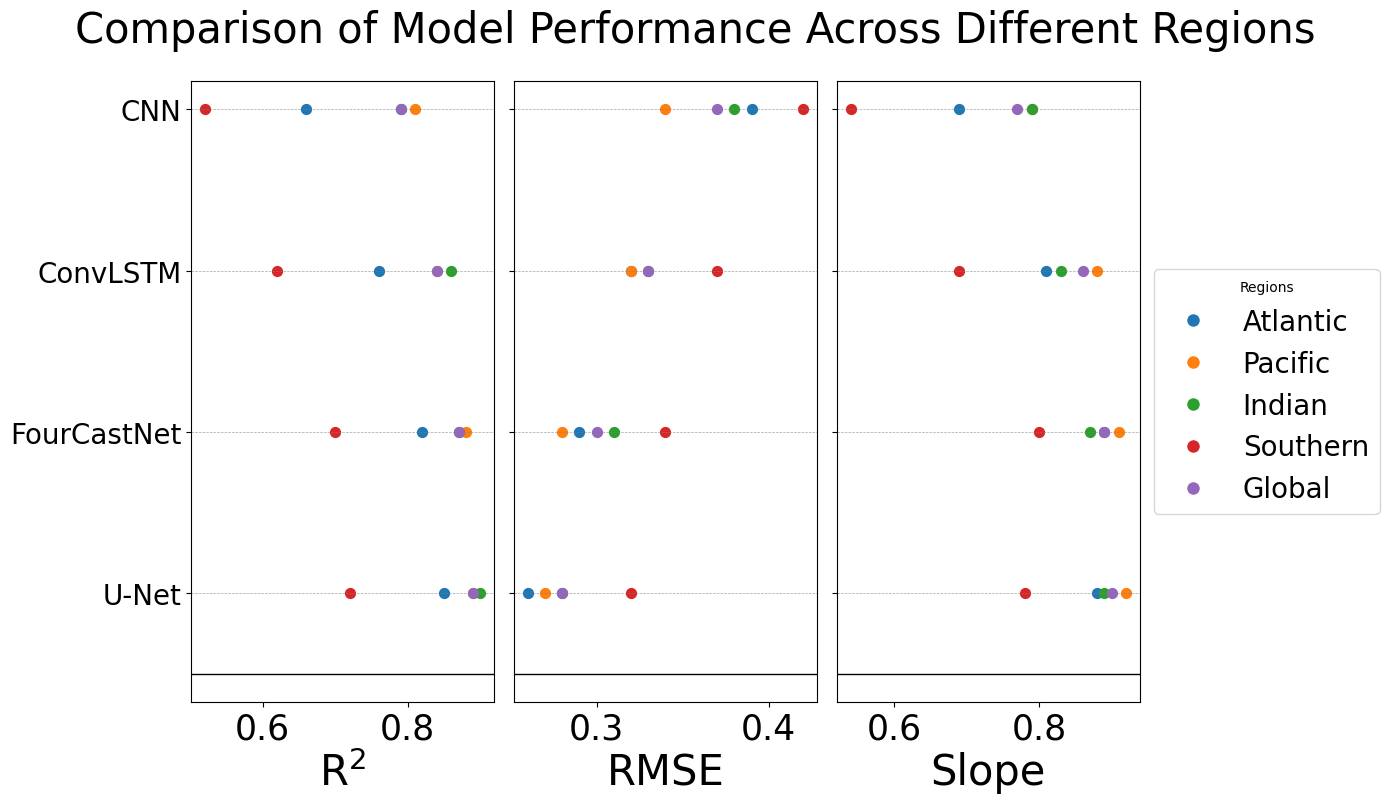

Recent advancements in reconstructing Chlorophyll-a concentrations utilize machine learning techniques, specifically Multi-Layer Perceptron, Support Vector Regression, and UNet models, as alternatives to traditional statistical methods. These machine learning approaches demonstrate improved performance when utilizing predictors such as wind speed (U10, V10), surface currents (U, V), and Mean Dynamic Topography (MDT). Benchmarking indicates that the UNet model achieves a coefficient of determination (R^2) of 0.88 when employed in static emulator configurations, suggesting a substantial capacity to accurately represent Chlorophyll-a distributions based on these physical drivers.

Advanced deep learning models, including Static Emulators, Auto-Regressive Emulators, ConvLSTMs, and 4CastNet, are capable of representing intricate spatiotemporal dependencies within ocean color data. These models surpass traditional methods by capturing non-linear relationships and temporal evolution, leading to improved reconstruction and forecasting accuracy. Specifically, the UNetAR-6 model has demonstrated a strong correlation of 0.99 when applied to forecasting seasonal variability in Chlorophyll-a concentrations, indicating its effectiveness in predicting changes over time and across different locations.

Forecasting Ocean Health: Impact and Future Trajectory

The capacity to forecast phytoplankton biomass with greater precision hinges on the effective utilization of comprehensive datasets like the Ocean Colour Climate Change Initiative (OC-CCI) alongside sophisticated modeling approaches. These techniques move beyond simple observation, enabling the reconstruction of underlying biological signals obscured by seasonal variations and noise. By discerning these patterns, researchers can develop predictions that are demonstrably more accurate and reliable, offering a crucial advancement in marine ecosystem monitoring. This predictive capability is not merely academic; it underpins efforts to anticipate and mitigate the impacts of harmful algal blooms, assess the broader consequences of climate change on ocean health, and refine our understanding of the complex interplay between phytoplankton and the global carbon cycle.

Accurate phytoplankton biomass predictions offer critical insights into several pressing environmental challenges. Monitoring harmful algal blooms, which can devastate marine life and human health, becomes significantly more effective with predictive modeling, allowing for proactive mitigation strategies. Furthermore, these projections are essential for assessing the complex impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems, including shifts in species distribution and overall ecosystem health. Phytoplankton, as the base of the marine food web and key players in the CO_2 cycle, directly influence the global carbon cycle; therefore, improved understanding of their dynamics, facilitated by these predictive models, is vital for refining climate models and forecasting future climate scenarios.

Analysis reveals the UNetAR-1 model demonstrates a significant advancement in reconstructing phytoplankton biomass signals, achieving a remarkably low Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 33.9. This performance notably surpasses that of comparative models, including UNetAR-6, which registered an RMSE of 55.8, and UNetBest, which yielded a substantially higher RMSE of 110. The considerably reduced error rate indicates UNetAR-1’s superior ability to accurately capture the non-seasonal variations in phytoplankton concentrations, suggesting its potential as a highly effective tool for ecological monitoring and predictive modeling within marine environments.

Continued development centers on enhancing predictive capabilities through data synergy and algorithmic refinement. Researchers intend to merge these established models with a broader spectrum of oceanographic datasets – encompassing variables like sea surface temperature, salinity, nutrient levels, and current velocities – to create a more holistic and accurate representation of phytoplankton dynamics. Simultaneously, efforts are dedicated to devising more computationally efficient and resilient algorithms for data assimilation, enabling real-time integration of observational data and improved forecast precision. This pursuit of algorithmic robustness is crucial for handling the inherent complexities and uncertainties within marine ecosystems, ultimately leading to more reliable predictions of phytoplankton biomass and a deeper understanding of their role in global ocean health.

The pursuit of accurately modeling complex systems, as demonstrated by this work on phytoplankton dynamics, necessitates a holistic understanding of interconnectedness. The researchers effectively highlight how leveraging physical oceanographic predictors within a deep learning framework-specifically, a UNet-based auto-regressive approach-can improve forecasting capabilities. This echoes Barbara Liskov’s insight: “It’s one of the dangers of having a really good idea that you get too enamored with it and you don’t see all the things it won’t do.” A seemingly elegant model, like the one presented, must be rigorously tested against the full spectrum of oceanic variability; ignoring limitations risks breakdowns along those unseen boundaries. The success of the model rests not just on its predictive power, but on acknowledging the inherent complexities it simplifies.

Future Currents

The demonstrated capacity to emulate phytoplankton dynamics with deep learning is, predictably, not an end, but a refinement of the question. The pursuit of accurate forecasting invariably highlights the limitations of the predictors themselves. Physical oceanographic variables, while foundational, represent a simplification of a system governed by complex biochemical interactions and species-specific responses. Future work must address this imbalance, integrating biological data – nutrient availability, viral impacts, grazing pressure – not as ancillary information, but as core components of the predictive framework. The current reliance on auto-regressive models, while effective at capturing temporal coherence, also implies a certain structural rigidity; a sensitivity to initial conditions that may limit long-term predictive skill.

A pertinent consideration is the transferability of these models. The global ocean is not uniform. A UNet trained on one region will inevitably encounter conditions outside its experience elsewhere. Exploring architectures that facilitate adaptive learning, or explicitly incorporate uncertainty quantification, represents a crucial step. Moreover, the computational expense of these models, though diminishing, remains a barrier to real-time operational forecasting. Finding the optimal balance between model complexity and computational efficiency is a recurring challenge, a constant negotiation between detail and practicality.

Ultimately, the success of this approach rests not simply on improving predictive accuracy, but on fostering a more holistic understanding of marine ecosystems. The models are tools, and like all tools, they reveal as much about the observer as about the observed. The true test will not be whether the models can predict the next algal bloom, but whether they can illuminate the underlying principles governing life in the ocean.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04689.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- Hollywood is using “bounty hunters” to track AI companies misusing IP

- A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms Season 1 Finale Song: ‘Sixteen Tons’ Explained

- What time is the Single’s Inferno Season 5 reunion on Netflix?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- NBA 2K26 Season 5 Adds College Themed Content

- Mario Tennis Fever Review: Game, Set, Match

- 2026 Upcoming Games Release Schedule

- Beyond Linear Predictions: A New Simulator for Dynamic Networks

- 4. The Gamer’s Guide to AI Summarizer Tools

2026-02-05 13:59