As a seasoned film enthusiast with a deep appreciation for both traditional and innovative storytelling techniques, I find myself captivated by Barry Jenkins’ journey into the realm of all-digital filmmaking with ‘Mufasa.’ Having delved into the intricate world of puppetry and virtual sets, his imagination seems to know no bounds. His unique approach to filmmaking not only showcases his versatility as a director but also highlights his unwavering commitment to pushing the envelope in visual storytelling.

Barry Jenkins, acclaimed director of “Moonlight,” can’t help but wonder aloud: “In what universe would I, the creator of ‘Moonlight’, be crafting a prequel to ‘The Lion King’?” Despite the buzz surrounding his recent meal at Manuela, a restaurant near the production site for the upcoming Disney film titled “Mufasa,” Jenkins remains skeptical. Since 2020, this photorealistic animated project has been underway, with October 2024 marking its pencils-down phase. Jenkins has spent much of the past week reviewing final renderings from his team and requesting minor adjustments, as the whole thing needs to be finalized by November. He’s optimistic about the project’s progress, but even his confidence won’t silence the doubters.

As a movie reviewer, I find myself compelled to express my thoughts on the Super Bowl, but it seems that every time I do, someone feels the need to remind me that I’m in the midst of crafting this very film. Frankly, I just can’t help but exclaim: “I simply must share my perspective on the Super Bowl, yet it appears I’m constantly reminded that I’m engrossed in creating this movie! I cannot escape that fact!

The backlash started in September 2020 upon Disney’s announcement that they would produce Mufasa with Jenkins as director, and it intensified further when Jenkins showcased sneak peeks at Disney’s fan event in August 2024. Some reactions were “Stop making these cash-grab movies and just make good ones already!” and “Let’s not sugarcoat it; Disney’s ability to write a check that sounds like a falling anvil is a significant factor behind his involvement.

In the scenario, Jenkins chose to take on the challenge of directing a big-budget studio film based on an established IP, despite the potential risks and pressures. This is not unlike a child playing with a toy steering wheel in a car, making engine noises. However, some directors have stepped away from such roles after realizing they were more like playful passengers than actual drivers.

Initially, when I accepted this position, there were questions like, “What visual effects expertise does Barry Jenkins have? What makes him suitable for this film?” and “Why is he working on The Lion King?” He reflects. What attracted him to the challenge was the skepticism; it felt energizing. After all, modern technology allows anyone to create such things, so why not him? He reasoned that there’s nothing inherently preventing him from doing this work.

Jenkins’s aesthetic stands in stark contrast to Disney’s animated films, not merely due to his previous movies being rated R, but primarily because of his approach to filmmaking. He immerses himself in the environment where he shoots, adapting his plan and reshaping everything spontaneously, much like John Cassavetes, Spike Lee, Martin Scorsese, Wong Kar-wai, and other directors whose works he reveres. His decisions are not solely influenced by the actors’ performances but also by the urban landscapes, seas, mountains, sunlight, and moonlight that encompass them. He abandoned this improvisational style during the making of Mufasa, which was filmed on a bare motion-capture stage. However, he subsequently spent several years exploring means to reinstate it.

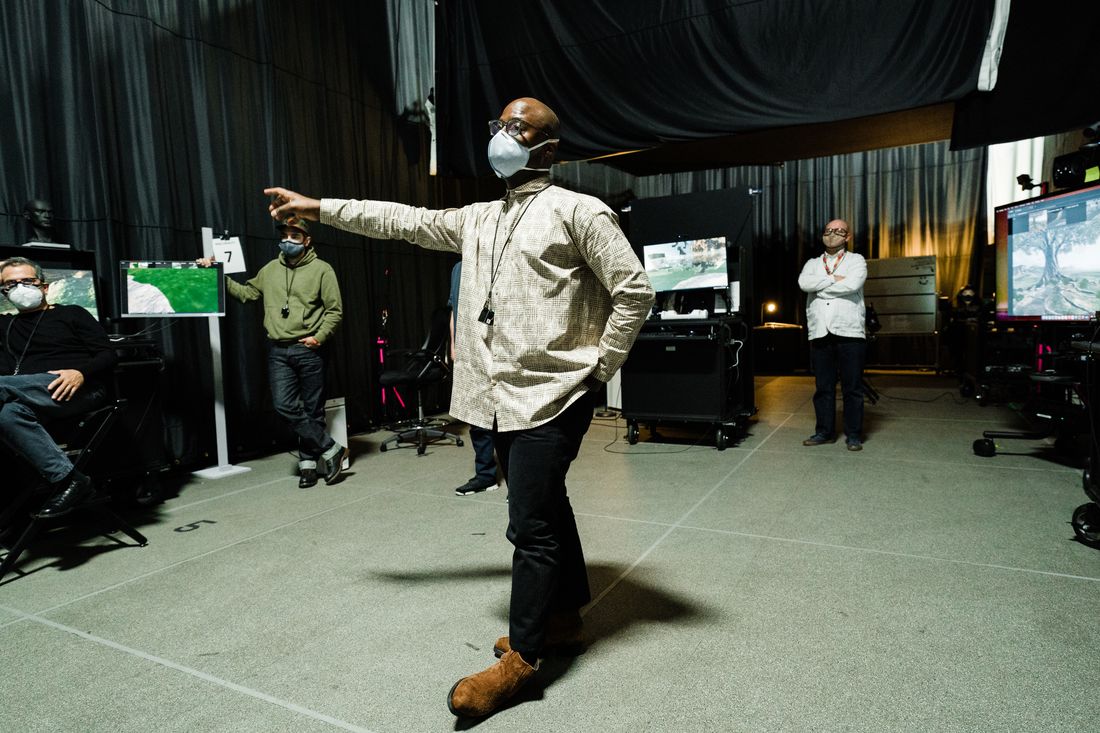

Jenkins’ motion-capture stage isn’t like a raised platform in a theater; it’s a large, open area in a spacious room with high ceilings, similar to a high school gymnasium. Overhead are lighting bars and a worn, tape-marked grid on the floor. I wasn’t given a script before being invited here. Even after viewing just 30 disjointed minutes of ‘Mufasa’, I can’t guess the movie’s plot because I signed a confidentiality agreement. However, Disney describes it as an epic adventure that revolves around the budding friendship between young, orphaned Mufasa and a lion named Taka, who is part of a royal lineage. This story is shared by the prophetic mandrill Rafiki, with the comical duo of Timon the meerkat and Pumbaa the warthog providing commentary from the sidelines.

I gesture towards the ceiling and ask when they turned off the movie lights. Jenkins explains that there were never any movie lights, only the regular bulbs already installed when they moved in November 2021. I then enquire about when the sets were dismantled. Jenkins reveals that during the 147 days he, his team of animators, and cinematographer James Laxton—all of whom met at Florida State University’s film school in the 1990s—filmed the movie without any sets. Filming concluded in August 2023. Interestingly, unlike other effects-driven franchises like Marvel or DC, or even previous Disney “live-action animation” movies such as Jon Favreau’s The Jungle Book, there were no set remnants left behind. No remains of Pride Rock, no fiberglass miniatures of canyons. Nothing at all.

In Jenkins’ workspace, as well as that of his editor and friend Joi McMillon, there was an abundance of visual resources, such as Sungi Mlengeya and Calida Rawles’ paint reproductions, photos by Jeremy Snell, Jalan, and Jibril Durimel, and John Powers’ book on Wong Kar-wai titled “WKW”. A wall showcased concept art of ‘Mufasa’, featuring a close-up shot of Rafiki appearing to make direct eye contact with the observer. This type of intimate framing is characteristic in Jenkins’ entire body of work, like the alternating close-ups of young Chiron and his mother in “Moonlight” during her conversation about concerns for him, or the poignant moment in “If Beale Street Could Talk” when Tish pleads with her mother Sharon through their small kitchen, and her mother senses the intensity of the gaze and turns to respond.

Over the next two days, I’ll work alongside Jenkins, McMillon, and their team in an editing suite and a medium-sized screening room. They will show me a variety of sequences, including action scenes on a grand scale, a dream sequence featuring an ice cave (which was ultimately removed from the film), a walk-and-talk with young Mufasa and Rafiki, and a scene involving these characters at a watering hole. At first sight, these scenes appear to be similar to Favreau’s 2019 remake of The Lion King, which had a more documentary-like feel compared to Disney’s hand-drawn ’90s hits. However, the animals and their environments in Mufasa are also photorealistic, with slight anthropomorphic body language and human voices synchronized with their “lip movements.

However, here are some unique, surrealistic elements I noticed in this version that weren’t present in Mufasa’s earlier story. For instance, a cloud resembles a lion’s head, and for a moment, the water reflects Mufasa’s family and himself as a cub. The visual style also strays from traditional Disney-cartoon aesthetics by employing techniques similar to those mastered by slow-cinema filmmakers such as Béla Tarr, Jia Zhangke, and Gus Van Sant. Although the parent company suggested that one of the long takes seemed a bit “slow,” there was no mandate for Jenkins to modify it.

Jenkins mentions they aimed to shoot the scenes with minimal takes. However, it wasn’t necessary for them to approach the process that way.

It’s unlikely that future film enthusiasts will reflect on watching “Sátántangó” and find it reminiscent of their childhood, but this Disney animal movie may be the first to evoke such feelings in them.

Prior to entering his Alameda Boulevard workspace, Jenkins received a script from Disney penned by Jeff Nathanson. This happened in July 2020, just before he was due for a vacation with his partner, Lulu Wang, the director of The Farewell. At first, he thought he’d simply wait a few days, call his agent, and decline the project. However, as they drove through wine country, the script lingered in the back of his mind. Upon returning home, he recollected, “Ah, right! I need to remind my agents tomorrow that I won’t be taking on this project.” That’s when Lulu asked, “Are you scared to read it?” He had planned to skim five pages but ended up reading 50. Suddenly, he turned to Lulu and exclaimed, “Wow, this is really good!

Following his eager anticipation towards Disney, Jenkins discovered that working on ‘Mufasa’ would necessitate at least three years of full commitment from him. This significant time investment was quite intimidating, particularly for Jenkins’s crew – Laxton, McMillon, producers Mark Ceryak and Adele Romanski, and production designer Mark Friedberg – all of whom expressed apprehensions about creating photorealistic animal movies under the Disney banner. Romanski admitted that ‘Mufasa’ initially seemed unlike the kind of filmmaking they were accustomed to, sparking numerous discussions about how they could innovate and elevate it if they decided to take on the project.

The team’s decision to take on Mufasa wasn’t solely driven by the prospect of working in a new medium, although that became an attractive option. According to Jenkins, they were all at a stage in their careers where they were ready to swap turbulence for order. They had recently navigated the tumultuous postproduction phase of The Underground Railroad, a project that was so intricate, costly, and fraught with backstage turmoil that, under slightly worse circumstances, it could have mirrored Jenkins’s own Heaven’s Gate. Amazon estimated the series to be over budget by tens of millions of dollars eight weeks before any shooting commenced – after they had already constructed all the railroad sets – and warned them that the project would be canceled if the costs didn’t decrease. Despite these challenges, The Underground Railroad was eventually brought to fruition in accordance with Jenkins’s initial vision, albeit with stringent cost-cutting measures (such as filming the entire series in Georgia instead of various states) and additional supervision from an Amazon-appointed line producer whose role was to help them finish the show within their remaining budget. (Amazon MGM Studios did not respond to a request for comment.)

After experiencing so much stress, the concept of creating a movie entirely digitally didn’t seem that daunting. Jenkins also felt it would be beneficial for his personal life to work in Los Angeles, as he and Wang cohabit there, despite being in a relationship for two years at that time, they frequently found themselves in different locations, with him in Georgia and Lulu in Hong Kong or elsewhere. In essence: “I needed to take a break … from the rush.

As a passionate cinephile, I was thrilled when in late 2020 and early 2021, I found myself collaborating with Disney artists, led by visual effects supervisor Adam Valdez and animation director Daniel Fotheringham – both veterans from Jon Favreau’s “The Lion King” project. Together with these talented individuals, we embarked on creating a test sequence. Producer Romanski describes it as our educational endeavor, where the first piece we constructed was a tranquil scene under a shade tree. This was essentially a trial run for us to grasp the entire process of crafting a single movie scene from scratch. We utilized an early, makeshift version of the technology that would eventually be employed in the film, according to Valdez, who likened it to assembling a DIY project using available resources, or in simpler terms, “kit-bashing” it together.

What Do You Call This Type of Movie, Anyway?

The term “live action” may be used to describe it by Disney CEO Bob Iger, however, this label can be somewhat deceiving when you take into account the large amount of digital data that forms these films. While recent adaptations such as The Jungle Book, The Lion King, Dumbo, and Aladdin are primarily created using Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI), characters like Mufasa can be considered entirely animated. Producer Adele Romanski refers to this genre as “photoreal animation,” while animation director Daniel Fotheringham accepts both terms but prefers “virtual production” since he believes that the work on movies like Mufasa has evolved beyond traditional animation into a more advanced, “iterative” method of visual storytelling.

The setting was within a digital environment designed by Friedberg and his team, utilizing Unreal Engine – a 3D graphics software often employed in popular multiplayer games like Fortnite, but adapted for use in special effects by Industrial Light & Magic for heavy-effect films and TV series such as The Mandalorian, Westworld, and the 2019 Lion King. Jenkins & Co. navigated Friedberg’s sets with VR goggles on, while Disney equipped Laxton with an Unreal VCam – a virtual camera that mimics traditional cinematography in a digital landscape. Essentially, it was like recording a first-person video game environment instead of playing the game, with the movements between the physical world and the virtual grasslands being more responsive and accurate.

In his home, Laxton mastered operating the camera. He could traverse the digital landscape either by taking single steps or, with a button press, move 100 meters instantly or even fly. As Valdez explains, “If you imagine yourself as a helicopter hovering over something while you’re walking in a ten-foot circle, you can decide to consider that a 100-foot circle and adjust your movements so you don’t bob up and down.” For the actual shoot, a small group convened in the same Alameda location, creating what Jenkins referred to as an “early draft” synchronized with voiceovers from a temporary cast of non-actors. Later, a team of animators and special effects artists in London refined this sequence over several months, parts of which eventually appeared in the final movie.

Romanski explains that the test sequence was initially challenging to grasp, until one went through it and realized, “It’s just like movie-making, but it’s all virtual.” Jenkins adapted swiftly to the process requirements, possibly due to his lifelong experience with video games. This was facilitated by consulting experienced filmmakers in this type of production, such as Favreau, Matt Reeves (known for ‘The Batman’ and ‘War for the Planet of the Apes’), and his old Florida State film-school classmate Wes Ball (the ‘Maze Runner’ films, ‘Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes’), and by visiting the set of James Cameron’s ‘Avatar: The Way of Water’.

Romanski inquired, “Has anyone of us made a film that was virtual, a franchise movie, a Disney production, or a Disney ‘heritage’ film?” To which the response was, “No, not yet! Isn’t it monotonous to keep repeating the same thing?

After that, Jenkins’s team embarked on an exciting journey, initially mimicking the path set by pioneer Favreau, whose 2016 adaptation of The Jungle Book featured a live-action star named Neel Sethi and incorporated bits of real rock formations and artificial jungles. However, for the director’s subsequent venture into this method, the 2019 remake of The Lion King, there were no human actors involved, thus no physical sets. Instead, it was filmed similar to the Mufasa test sequence: on landscapes created with 3-D imaging software, which the crew (including cinematographer Caleb Deschanel) navigated while wearing VR goggles or looking at the screen of a handheld VCam. Filmmakers would “explore” locations in this manner and plan out scenes as if they were moving through a real environment.

Jenkins, who is always eager to uncover hidden secrets and mysteries, was fascinated by this particular part of the production. As producer Ceryak puts it, “Jenkins has a knack for exploration and often stumbles upon fascinating finds while working on set.” This behavior of Jenkins’ was quite common; he would frequently be discovered exploring Friedberg’s virtual landscapes, exclaiming excitedly for his team to gather around as he pointed out some amazing discovery. In the words of Ceryak, “We were usually focusing on a specific area for a scene, like a passageway or valley where our characters were walking and talking. But then suddenly Jenkins would be off in the corner, underwater, behind a rock – calling out to James to fly over and check out this hidden gem that Friedberg had built, even though it wasn’t intended for the movie.

Back in early 2021, I found myself standing alongside some incredible talents – Beyoncé, Aaron Pierre, Mads Mikkelsen, Keith David, and Thandiwe Newton – on sets scattered across the US and beyond, as we brought Mufasa‘s characters to life under Jenkins’s guidance. Microphones captured our spoken lines, while cameras meticulously recorded every nuance of our expressions and movements for future reference by the animators. Editor McMillon skillfully pieced together the finest takes to form what Jenkins refers to as the “radio play” version of Mufasa. This was then combined with roughly animated storyboards, creating an animatic that served as a blueprint, showing us how each scene and sequence would flow together and helping us identify any potential pacing issues.

The unique aspect in the production of Mufasa that allowed Barry Jenkins and his team to create a film with talking animals was a technique called quadruped capture. This process captures the movements of human actors dressed in black bodysuits marked with sensors as they move around on a stage, and instantly turns these movements into those of four-legged creatures in the movie’s digital environment. The Mufasa team referred to this part of the process as “staging,” similar to how a theater director arranges onstage action relative to the proscenium arch. Staging Favreau’s The Lion King was challenging, as the four-legged characters were developed through a multi-step process that has been used in digital films since the Star Wars prequels. This process started with animatics and progressed to 3D wireframes or geometric figures, followed by highly detailed creatures with fur, feathers, or scales whose movements and textures were derived from real animals. During Favreau’s The Lion King shoot, there were no physical animal stand-ins, only digital placeholders that resembled moving chess pieces.

Initially during filming, Jenkins encountered difficulties as he lacked means for improvisation on set, resulting in him capturing nothing but emptiness. As Romanski puts it, “James was aimlessly pointing the camera.” However, due to their prolonged work on the movie, they managed to stay ahead of technological advancements, with quadcapping eventually being introduced midway through production. Quadcapping enabled the conversion of animators’ movements in bodysuits (described by Jenkins as a “rotating group,” although Fotheringham was the most frequent wearer) into virtual animals moving through Friedberg’s virtual Africa. According to Fotheringham, these virtual creatures could convey emotions like nervousness, embarrassment, excitement, or anger simply through their movements, allowing the camera to react and anticipate these movements, creating a more immersive experience for the audience.

During motion-capture sessions, a PA system played back the “radio edit” of scenes to motivate animators in bodysuits, helping them understand the timing of their actions as they traversed the floor. Jenkins provided instructions and feedback based on what he observed in both real and virtual environments. As Fotheringham explains, “The motion-capture stage was divided by large grid lines with coordinates like A7 and G5, which were then projected into the virtual world so everyone could see the performers as lions.” For scenes requiring larger obstacles, such as Pride Rock or a tree, the system would adjust the lion characters’ heights or translate circular movements around the stage into straight-line movement over rolling hills. Fotheringham likens this to a tartan blanket being stretched over pillows – the blanket distorts but the tartan grid remains consistent. The virtual lions followed this distorted grid in a similar manner. Animators at workstations surrounding the stage monitored the results on their screens, made adjustments, corrected movements in real-time, and filled in missing details. Valdez referred to them as “the rapid-response team.

In the process of controlling everything, Jenkins came to a revelation: “In traditional computer animation, we think of animators as writing with code. However, with quadcapping, animators get an initial draft of the animation when they’re wearing the suits, which is akin to them writing with their bodies.” Regrettably, for grand-scale action scenes involving numerous animals, like the flood scene in Mufasa, the team had no choice but to adopt modern 2019 animation techniques since it was impractical to have more than four animators in bodysuits on the stage at once. The required space and technology hadn’t advanced enough for that yet.

The quality of the quadcapped visuals is not sufficient for screening them in a theater for paying viewers, as Jenkins refers to it as “the PS3 footage.” This subpar footage caused Jenkins frustration when some of it was leaked earlier this year. McMillon hadn’t received the footage yet to edit and pass on to the animators and visual effects artists led by Fotheringham and Valdez, followed by a team of colorists, texture painters, lighting designers, and other specialists for refinement. This process, which takes roughly six weeks per scene before revisions, might still require additional adjustments based on Jenkins’ notes. In some instances, if Jenkins and Laxton felt the original take wasn’t satisfactory, they would return to the set to reshoot all or part of a scene, as post-production enhancement wouldn’t suffice in those cases.

Jenkins finds ‘stacked’ an intriguing term to describe the production, as each section of the film might simultaneously be in pre-production, production, post-production, or finalization stages,” is a natural and easy-to-read paraphrase.

According to Fotheringham’s description, the unique charm of Mufasa lay in its capability of building an intricate animated world that was accessible for anyone, even those without prior experience in animation, allowing them to easily dive in and produce their own films.

On my final day at Mufasa headquarters, I spend time in the screening room sandwiched between Jenkins and McMillon. This is where they’re showing final-stage shots to the director for approval. Jenkins is a multitasking whirlwind, juggling conversations with the projectionist, department heads on Zoom, and several people in the room. He’s known for both praising generously and playfully teasing. When he introduces me to Fotheringham, he warns him, “This man has seen you in a bodysuit.” And his team joins in the fun: When Jenkins asks visual-effects producer Mark St. John to tell me his job title, St. John replies “Doormat,” and the room bursts into laughter. For the next three hours, Jenkins swiftly reviews all the footage. A simple “Approved” means a sequence is ready, and he uses this word more than any other. However, for one scene, he asks for a slightly narrower lens to enhance the perspective of a lion shot. For another, he requests a less intense surrealistic sound effect because he wants the audience to actively decipher the meaning instead of having it handed to them.

Throughout the production of “Mufasa”, Jenkins emphasized, “Embrace imperfection.” He and Laxton appreciated organic touches, like a sudden camera jolt that occurred when Laxton leapt to capture a lion bounding down a row of trees. They often had to resist Disney’s tendency towards perfection. During the filming of another action scene, Laxton accidentally tripped, but this mishap resulted in a memorable moment: “The lion cubs were racing, and due to the camera position and the cub’s movement, he ran through a puddle that reflected the sun, making everything appear very bright, like running through a flash,” Jenkins explained. “It looked as if the camera operator was on a speeding truck in a muddy field, fighting to maintain focus.” Laxton and Jenkins admired this mistake because it enhanced the authenticity of the scene being captured under pressure. When the animators removed the brief loss of control, Jenkins requested that the error be reinstated: “Don’t polish over the rough edges. Got it?

He expresses his desire for something with a tactile quality, something that seems natural or organic. However, achieving this can be challenging because every individual detail needs to be carefully crafted. Yet, the ultimate goal is to ensure it doesn’t appear as if it was created by just anyone; instead, it should seem like it sprung up naturally on its own.

When inquired about the key abilities he honed during the production of Mufasa, Jenkins humorously responds, “Mathematics.” This became apparent when Jenkins elaborated on how the budget for Mufasa was determined by calculating the labor needed to create a shot suitable for display on a large theater screen. To illustrate this mathematical process, he retrieves an old-fashioned gray plastic calculator and meticulously analyzes the budget, dividing it by cost per shot, cost per minute of screen time, and cost per frame. After working on The Underground Railroad, Jenkins seemed to have developed a yearning for control, which he appears to have found during this project.

If I inquire from members within Jenkins’ close-knit group if they’d be open to making another film similar to this one, the response is typically a cautious display of hesitation. It appears evident that while they cherish their achievement in tackling an innovative filmmaking challenge and gaining fresh skills, it seems unlikely they will produce another fully digital movie or one with such a colossal budget. Romanski suggests that Jenkins might direct a biopic about choreographer Alvin Ailey for Fox Searchlight, and he mentions that “it’s not going to be a $250 million film, correct? So we’ll need to revert to utilizing a more streamlined set of tools for this project.

Jenkins expresses his discomfort with all-digital filmmaking, stating firmly, “It’s not my style.” He then emphasizes his desire to return to the traditional method of filmmaking, where he can tangibly manipulate everything. He believes that what is available is sufficient for him to create a magical effect through chemistry. He wonders how he can assemble people, light, and environment to craft an image that moves, is beautiful, and carries a deep text – one that is thick enough, rich enough, to resonate with someone. This, he admits, cannot be achieved in a studio setting, even now.

Jenkins doesn’t dismiss the idea of employing techniques similar to those used in the Muppets to create new methods for making Barry Jenkins films. Intriguingly, he starts discussing the Muppets and envisions himself directing puppeteers and superimposing them onto digital backdrops. “Imagine a Muppet movie done this way would be fantastic,” he remarks. “Terrific.” He continues, “Just as we produce our PlayStation version of a scene, you could have a set that’s just the actual physical puppeteers, and the Muppets are blocking the scene but only in a black box, you understand?” he suggests. “Or, let’s say, a green box. You’re capturing their performances and then you’re placing them all into virtual sets. I can visualize how that could take shape.

Read More

- FARTCOIN PREDICTION. FARTCOIN cryptocurrency

- SUI PREDICTION. SUI cryptocurrency

- Excitement Brews in the Last Epoch Community: What Players Are Looking Forward To

- The Renegades Who Made A Woman Under the Influence

- RIF PREDICTION. RIF cryptocurrency

- Smite 2: Should Crowd Control for Damage Dealers Be Reduced?

- Is This Promotional Stand from Suicide Squad Worth Keeping? Reddit Weighs In!

- Epic Showdown: Persona vs Capcom – Fan Art Brings the Characters to Life

- Persona Music Showdown: Mass Destruction vs. Take Over – The Great Debate!

- “Irritating” Pokemon TCG Pocket mechanic is turning players off the game

2024-12-05 19:55