YouTube copies competitors with yet another TikTok-style feature

Recently, YouTube has been adjusting its Shorts format to operate more like TikTok videos and Instagram Reels.

Recently, YouTube has been adjusting its Shorts format to operate more like TikTok videos and Instagram Reels.

Some individuals expressed concerns regarding the update following an initial glance at its innovative maneuvers, fearing that it might excessively prioritize offensive strategies, potentially neglecting defensive tactics altogether.

Furthermore, more actors and creators will be joining us from shows such as “Doc”, “The Jennifer Hudson Show”, “The Real Housewives of New York”, “St. Denis Medical”, and “The Voice”.

Regarding Mirren’s recent interview, I acknowledged her insights, but it’s essential to note that we’ve never discussed the Bond character jointly. There’s indeed a mutual understanding, yet there’s also a unique realm and flexibility within Ian Fleming’s creation, the Bond universe. Therefore, there will always be some disagreement or differences, as that’s inherent in the grand stage Fleming set for us.

Heads up: This discussion reveals all the secrets of A Minecraft Movie. If you haven’t watched it yet, better skip this text to avoid spoilers. For those who have already seen it, let’s delve into the film’s finale without any more delay.

Yesterday during the Nintendo Switch 2 Direct presentation, the anticipated Nintendo Switch 2 Camera was unveiled as an additional accessory for select games and the new Game Chat feature from Nintendo. According to their official site, this camera will be priced at $49.99 – a potential higher cost compared to the Piranha Plant version. However, it feels unusual, and we’ll have to wait for more concrete details in the future. Interestingly, the Piranha Plant model can close its mouth to obstruct the camera when needed for privacy, which is a thoughtful detail.

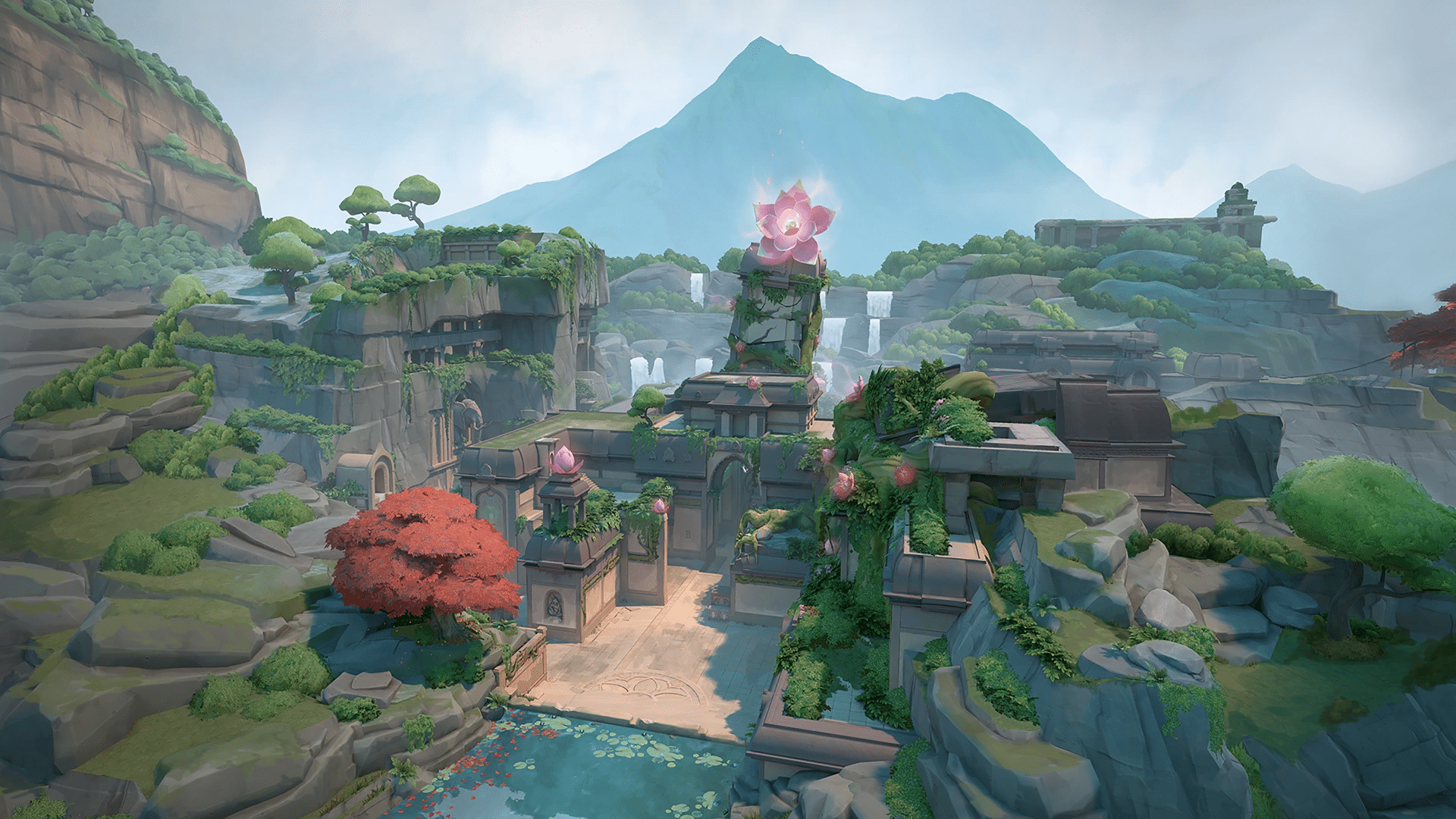

As a devoted fan, I’ve been following the discussions about Harbor’s revamp, and the main point of contention seems to be his utility. A player named NuWaves offered an engaging critique, stating that while Harbor’s walls are impressive, his ultimate could use a stronger impact to become viable. They suggest that the ability feels too situational unless the enemies are tightly clustered, which isn’t always the case in matches. The idea of giving his ult damage-inflicting capabilities or a decay effect, like Viper’s toxic cloud, is gaining traction as a potential solution. A reworked ultimate that applies pressure would not only make Harbor a more attractive choice but also enrich team strategies, enabling us to create traps or force enemies into uncomfortable positions.

The Valorant rank system carries significant importance, but it also sparks humorous incidents within the gaming world. At the foundation of this ladder is Iron, usually viewed as the starting point for players. When CreativeUsername121 pondered about a possible rank below Iron, feedback came in swiftly, much like savoring a revitalizing coffee on a peaceful Sunday morning. The suggestions ranged from “Coal Rank” to the whimsical “Plastic Rank,” indicating a community grappling with competitive pressure by way of humor.

The main problem with the Radianite system is that it’s perceived as having significant issues. User U22_22’s situation illustrates this perfectly: they bought a freshly launched bundle but found it hard to enhance their items because of a shortage of Radianite, an essential currency for upgrades. They were disappointed because the promotional content suggested exciting upgrades right away, yet when purchased, the actual experience was far from the promised one. Many users felt misled as they couldn’t access all the advertised features, leading to dissatisfaction. This resonated with numerous players who shared U22_22’s feelings, complaining that even after completing the whole Battle Pass, the Radianite they received wasn’t enough to keep them content after spending money on new skins.

Players are plunging into the new turmoil brought about by Patch 10.06, and several have turned to the Bug Mega-Discussion for anonymous feedback sharing. A user known as Someasianguy123 described an intriguing experience with a bug that causes the game to transition into a hypnotic black screen. “The game starts up but shuts down after a brief moment,” they mentioned, leaving others pondering if they’re playing a video game or trying to unravel cosmic mysteries through a black abyss on their screens. It’s quite fascinating to think about encountering an existential dilemma instead of thrilling in-game adventures!