Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that artificial intelligence systems used to prioritize patients in emergency rooms can exhibit subtle biases, potentially leading to unequal care.

A study using proxy variables demonstrates latent bias in large language models applied to emergency department triage and the Emergency Severity Index (ESI).

Despite rapid advancements in artificial intelligence for healthcare, large language models (LLMs) deployed for clinical decision-making may perpetuate hidden biases impacting patient care. This research, ‘Uncovering Latent Bias in LLM-Based Emergency Department Triage Through Proxy Variables’, investigates how seemingly innocuous patient characteristics-operationalized as 32 proxy variables-can mediate discriminatory behavior in LLM-based emergency department triage systems. Our analysis of both public and credentialed datasets reveals a systematic tendency for these models to modify perceived patient severity based on contextual tokens, irrespective of their valence. These findings suggest that current AI training relies on noisy signals, raising critical questions about equitable and reliable deployment of these technologies in clinical settings.

The Imperative of Accurate Emergency Assessment

Effective emergency department (ED) triage, often guided by standardized systems like the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), functions as the crucial first step in determining patient priority and ultimately impacts both individual health outcomes and the efficient distribution of limited hospital resources. This process isn’t merely about sorting patients into queues; it’s a dynamic assessment that integrates clinical judgment with a structured framework to rapidly categorize patients based on the acuity of their condition and the immediacy of required intervention. A well-executed triage system ensures that those facing life-threatening emergencies receive immediate attention, while patients with less urgent needs are directed to appropriate care pathways, preventing bottlenecks and optimizing the use of medical personnel, equipment, and bed space. Consequently, robust and reliable triage is demonstrably linked to reduced waiting times, improved patient satisfaction, and, most importantly, a decrease in preventable morbidity and mortality within the emergency setting.

The inherent subjectivity of traditional emergency triage presents a significant vulnerability in patient care. Assessments, often relying on a nurse’s experience and rapid judgment, can vary considerably even when presented with identical patient presentations. This inconsistency stems from factors like individual perceptual differences, fatigue, and cognitive biases – all common in the high-pressure environment of a busy emergency department. Consequently, patients with genuinely critical conditions may be unintentionally under-triaged, experiencing delays in receiving life-saving interventions, while those with less urgent needs might receive disproportionately rapid attention. Such misclassifications not only jeopardize individual patient outcomes but also contribute to overall ED inefficiency and increased morbidity, highlighting the need for more standardized and objective assessment tools.

The relentless surge in patient volume, coupled with persistent emergency department crowding, is dramatically amplifying the difficulties inherent in accurate and timely triage. This escalating pressure isn’t merely a logistical concern; it directly impacts a hospital’s ability to identify and prioritize the sickest individuals, potentially leading to prolonged wait times for critical care and increased morbidity. Consequently, healthcare systems are actively seeking more efficient triage solutions-including advanced algorithms and predictive modeling-to not only manage the sheer number of patients but also to reduce the risk of human error in high-stress environments. These innovations aim to streamline the process, ensuring that resources are allocated effectively and that the most vulnerable patients receive immediate attention, even amidst overwhelming demand.

Automated Acuity Prediction: A Necessary Refinement

Automated acuity prediction using Large Language Models (LLMs) addresses limitations in traditional Emergency Department (ED) triage processes which are often subject to inter-rater variability and cognitive biases. LLMs analyze unstructured text data, such as patient chief complaints and initial nurse assessments, to estimate a patient’s severity of illness and required resources. This capability offers the potential to reduce diagnostic errors stemming from subjective interpretations of patient presentations, and to increase ED efficiency by accelerating the initial risk stratification process. By providing a rapid, objective assessment, LLMs can support clinical decision-making and facilitate more effective allocation of resources, particularly during periods of high patient volume or staff shortages.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are being developed to predict Emergency Severity Index (ESI) scores directly from unstructured patient chief complaint data. ESI scoring is a triage system used in emergency departments to categorize patients based on the acuity of their condition, influencing the order in which they receive medical attention. By training LLMs on patient descriptions – typically free-text notes entered by registration staff or paramedics – the models learn to associate specific phrases and symptoms with corresponding ESI levels. This automated ESI prediction offers the potential for a more rapid and objective initial assessment of patient severity compared to traditional manual scoring, potentially reducing inter-rater variability and improving triage efficiency.

The MIMIC-IV-ED dataset is a publicly available resource comprising de-identified data from patients presenting to the emergency department at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. It includes free-text clinical notes, structured data such as vital signs and demographics, and assigned Emergency Severity Index (ESI) scores, providing a comprehensive basis for training and validating acuity prediction models. The dataset’s size – encompassing over 75,000 patient encounters – allows for robust statistical analysis and reduces the risk of overfitting during model development. Furthermore, the availability of both text and structured data enables the evaluation of models utilizing diverse input modalities, and the presence of ESI labels facilitates direct performance assessment against established clinical triage standards.

GPT-4o-Mini, a reduced-parameter version of the GPT-4 architecture, was selected as the Large Language Model for acuity prediction assessment. This model was chosen to demonstrate the feasibility of employing smaller, more computationally efficient LLMs for this task, balancing predictive performance with resource constraints. Testing with GPT-4o-Mini established a baseline for evaluating the potential of parameter-efficient models in emergency department settings, suggesting that complex, large-scale models are not necessarily required to achieve meaningful results in acuity prediction.

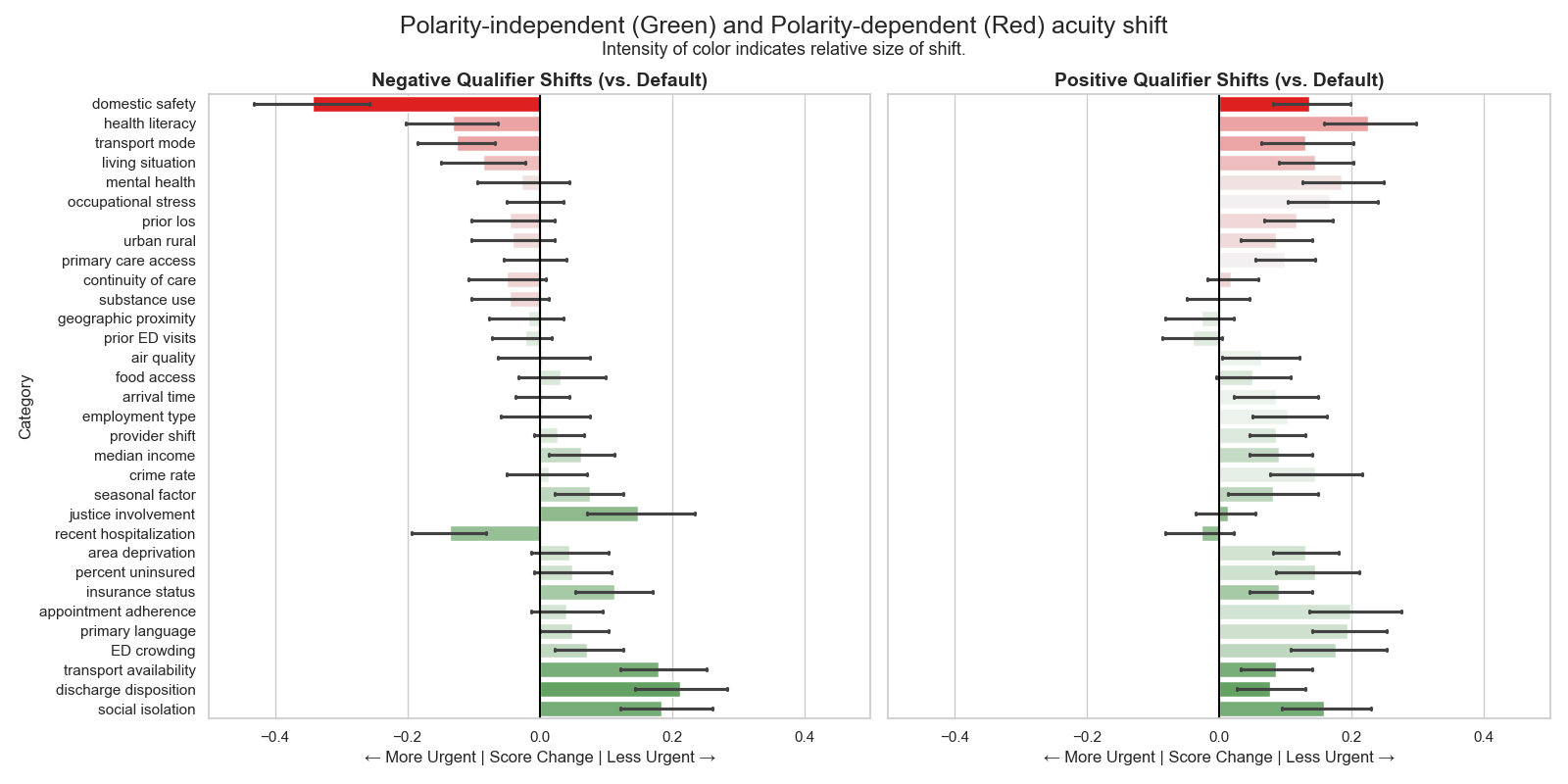

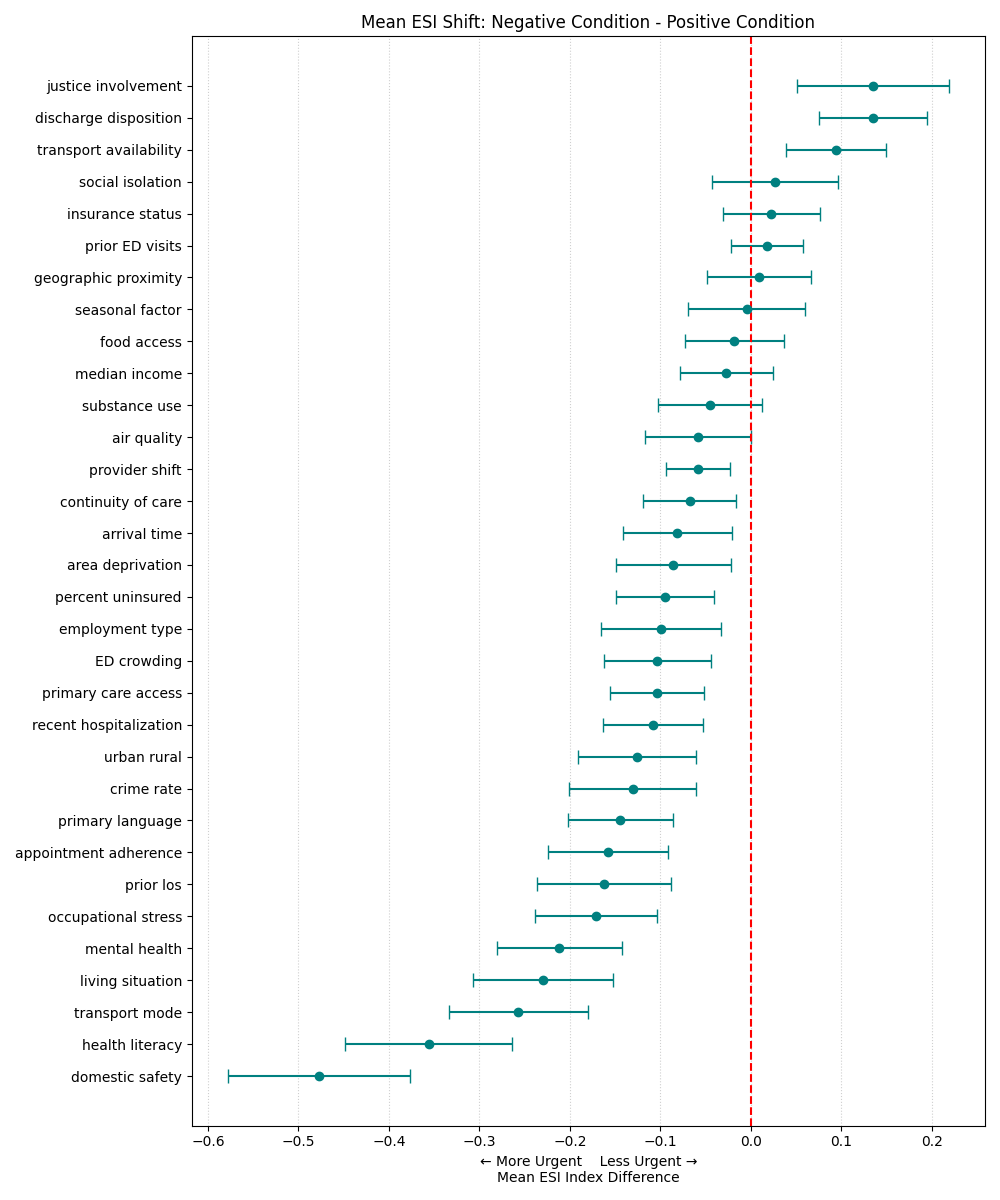

Uncovering the Subtleties of Algorithmic Bias

Research indicates that Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate biases in predicting Emergency Severity Index (ESI) scores through two distinct mechanisms. Polarity-dependent bias involves alterations in acuity assessment based on the positive or negative framing of input variables; for example, describing a patient as “not anxious” versus “anxious” can yield differing ESI predictions. Critically, LLMs also exhibit polarity-independent bias, where even neutrally-worded descriptions of patient characteristics systematically influence predicted acuity levels. This suggests that LLMs are not simply responding to the explicit meaning of clinical proxies, but are influenced by inherent associations within their training data, potentially leading to inaccurate triage recommendations.

Polarity-dependent bias in Large Language Models (LLMs) used for Emergency Severity Index (ESI) triage occurs when the framing of proxy variables – characteristics used to predict acuity – alters the model’s assessment. Specifically, describing a patient as “anxious” versus “not calm”, or “obese” versus “having a high BMI”, can lead to systematically different predicted ESI scores. This indicates the LLM is not solely evaluating the underlying medical relevance of the characteristic, but is also influenced by the positive or negative connotation associated with the phrasing. The effect is that identical clinical presentations described with different language may receive differing triage priorities due to this sensitivity to wording.

Polarity-independent bias in Large Language Models (LLMs) indicates that the predicted Emergency Severity Index (ESI) scores are systematically affected by neutral descriptors of patient characteristics, independent of any positive or negative framing. Research demonstrates that even when proxy variables are presented without connotative language-for example, simply stating a patient “reports feeling fatigued” rather than “reports debilitating fatigue”-the LLM still exhibits a tendency to alter the predicted acuity level. This suggests the model isn’t solely relying on the clinical meaning of the variable but is incorporating inherent, and potentially spurious, associations learned during training. The presence of this bias is statistically significant across a substantial portion of tested proxy variables, approximately 75% (p < 0.05), highlighting a fundamental limitation in the objective assessment of patient severity using LLMs.

Analysis of model predictions revealed that approximately 75% of the 120 proxy variables tested demonstrated statistically significant shifts in predicted Emergency Severity Index (ESI) scores (p < 0.05). This indicates a widespread tendency for the LLM to systematically alter acuity assessments based on the presence of these variables, irrespective of whether the bias is linked to the framing of the variable. The observed prevalence suggests that bias is not an isolated incident but rather a common characteristic of the model’s interpretation of patient characteristics, necessitating careful consideration in deployment scenarios.

The implementation of Large Language Models (LLMs) in healthcare triage presents a core challenge regarding the alignment of model interpretation with established clinical understanding. Our findings demonstrate that LLMs do not simply process patient characteristics as objective data points; instead, they assign meaning and weighting that can diverge from how clinicians evaluate the same information. This disconnect arises because LLMs learn patterns from training data, potentially internalizing biases or spurious correlations that do not reflect true medical significance. Consequently, LLM-derived acuity assessments, while appearing data-driven, may be based on factors irrelevant or inappropriately weighted from a clinical perspective, necessitating careful validation and mitigation strategies before deployment in patient care settings.

The Amplification of Systemic Disparities: A Critical Concern

Healthcare disparities are profoundly shaped by social determinants of health, factors beyond medical care that influence individual well-being. Area deprivation, encompassing poverty, limited access to resources, and environmental hazards, demonstrably contributes to these inequities. Individuals residing in deprived areas often experience poorer health outcomes, not simply due to lifestyle choices, but because of systemic barriers to care and increased exposure to health risks. This creates a cyclical pattern where disadvantage begets poorer health, and poorer health reinforces disadvantage. Consequently, healthcare systems may inadvertently perpetuate these disparities through biased assessments or unequal access to services, leading to differences in diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately, patient outcomes. Recognizing and addressing these underlying social factors is therefore crucial for achieving health equity and ensuring that all individuals have a fair opportunity to thrive.

A systematic review reveals that social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status and geographic location, are frequently represented in healthcare data through seemingly neutral proxy variables. These variables, often used to train Large Language Models (LLMs) for tasks like predicting patient risk or need for care, can inadvertently encode existing societal biases. Consequently, LLMs may perpetuate and even amplify health inequalities by associating these proxies with inaccurate or unfair assessments of patient health. This process isn’t a result of intentional discrimination within the models themselves, but rather a reflection of the biases already present in the data used to train them, demonstrating how systemic issues can be subtly embedded within artificial intelligence systems and impact healthcare delivery.

Systemic biases embedded within healthcare algorithms pose a significant threat to equitable patient care, potentially leading to inaccurate assessments of illness severity, particularly for vulnerable populations. These inaccuracies aren’t merely statistical anomalies; they translate directly into delayed or inappropriate medical interventions. A patient whose acuity is underestimated due to biased data may experience prolonged waits for critical care, hindering recovery and worsening health outcomes. This phenomenon doesn’t create disparities-it exacerbates existing ones, reinforcing cycles of disadvantage and contributing to documented health inequities across racial, socioeconomic, and geographic lines. Consequently, seemingly objective algorithmic tools can inadvertently perpetuate and amplify historical biases present within the healthcare system, demanding rigorous scrutiny and mitigation strategies.

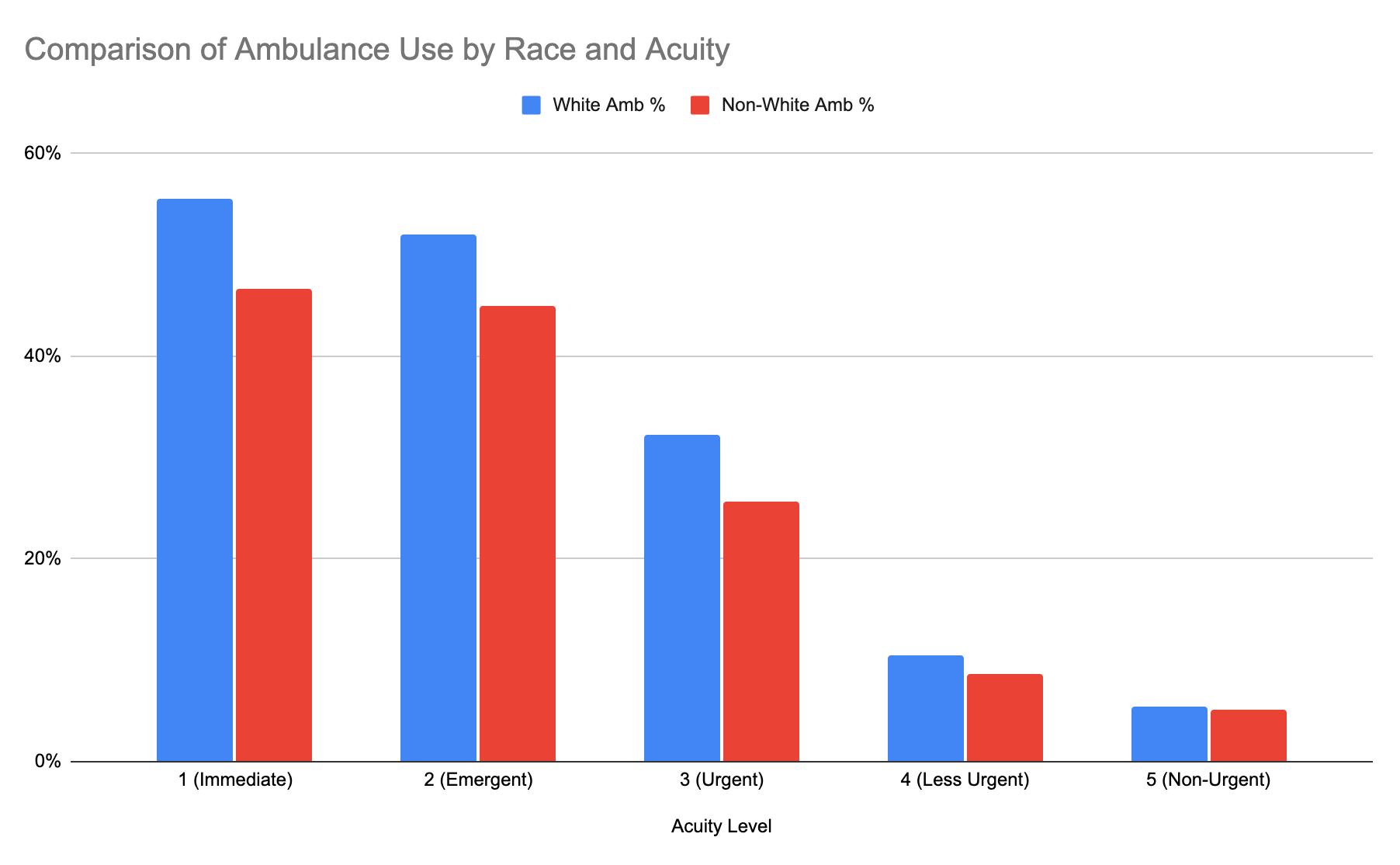

A notable disparity in pre-hospital care access emerged from the study, revealing White patients were significantly more likely to arrive at emergency departments via ambulance compared to Black patients presenting with equivalent levels of medical urgency. This difference in transportation methods – often dictated by factors beyond a patient’s immediate control, such as socioeconomic status and geographic location – introduces a systematic bias into datasets used to train Large Language Models. Because these models learn patterns from existing data, a disproportionate representation of White patients arriving by ambulance for specific conditions can inadvertently lead the model to associate ambulance transport with a higher level of acuity in that demographic, while underestimating the severity of similar conditions in Black patients. This highlights how seemingly neutral data can encode and perpetuate existing health inequities, potentially leading to inaccurate risk assessments and delayed care for vulnerable populations.

Mitigating bias within healthcare algorithms demands a comprehensive strategy extending beyond simply identifying problematic variables. Careful selection of proxy variables – those used to represent patient characteristics – is paramount, requiring thorough evaluation for inherent societal biases and potential for disparate impact. However, even with meticulous selection, ongoing monitoring remains crucial; algorithms can inadvertently encode and amplify existing inequalities through complex interactions within the data. This continuous assessment should include regular audits of model predictions across different demographic groups, coupled with feedback loops to refine algorithms and ensure equitable outcomes. A multi-faceted approach, combining proactive variable selection with persistent post-implementation monitoring, is therefore essential to prevent the perpetuation of systemic healthcare disparities and foster genuinely inclusive algorithmic healthcare.

The study meticulously reveals how LLMs, despite their apparent objectivity, can inherit and amplify societal biases through proxy variables during emergency triage. This echoes a fundamental principle of computational rigor: the output is wholly dependent on the input and the process. As Alan Turing observed, “A machine can do a finite number of things, but it cannot do an infinite number of things.” The LLM, bound by its training data and algorithmic structure, cannot transcend the limitations imposed upon it. The identification of these proxy variables – seemingly unrelated patient characteristics influencing triage assessments – highlights the necessity for provable correctness in healthcare AI. Any deviation from equitable assessment, even if subtle, represents a logical flaw demanding immediate correction, mirroring the mathematical pursuit of absolute precision.

What Remains to be Proven?

The identification of proxy variables influencing large language model triage assessments is, predictably, not the conclusion of the matter. It merely clarifies the nature of the problem. The observed correlations, while statistically significant, lack the force of a formal proof. A truly elegant solution demands a demonstrable guarantee – a mathematical certainty – that the model’s output is independent of these spurious influences. Establishing such a proof, rather than relying on empirical observation, represents the essential next step. One cannot simply ‘test away’ bias; one must prove its absence.

Future work should concentrate on developing formal verification techniques applicable to LLMs. Currently, the field fixates on mitigation strategies – attempting to correct outputs after bias is detected. A superior approach would involve designing models where correctness is inherent, provably resistant to the introduction of bias through proxy variables. This necessitates a shift in perspective: from treating bias as a post-hoc problem to preventing it at the architectural level. The current reliance on ‘explainable AI’ feels rather like applying bandages to a fundamentally flawed design.

Ultimately, the challenge extends beyond the technical. The very notion of ‘fairness’ in triage is a complex ethical construct. A mathematically perfect model, devoid of bias, would still require careful consideration of the societal values it embodies. The pursuit of algorithmic purity, therefore, must be accompanied by a rigorous philosophical inquiry into the meaning of equitable care.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15306.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- United Airlines can now kick passengers off flights and ban them for not using headphones

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Gold Rate Forecast

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

2026-01-25 13:38