Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores whether artificial intelligence can anticipate human decisions in everyday conversations, even when we’re influenced by subtle biases.

This study investigates the capacity of large language models to predict human susceptibility to framing and status quo biases in conversational settings, factoring in the impact of cognitive load.

Despite decades of research into human cognitive biases, predicting individual decision-making-particularly as influenced by conversational context-remains a significant challenge. This research, ‘Predicting Biased Human Decision-Making with Large Language Models in Conversational Settings’, investigates the capacity of large language models (LLMs) to forecast biased choices-specifically framing and status quo biases-under varying cognitive load, as demonstrated in a study with \mathcal{N}=1,648 participants. The findings reveal that LLMs, especially those in the GPT-4 family, can not only predict individual decisions with accuracy but also replicate the observed interaction between cognitive load and biased behavior. Could these models provide a pathway toward building more adaptive conversational agents that account for-and potentially mitigate-human biases?

The Architecture of Choice: Understanding Systematic Deviations

Human choices, despite often appearing deliberate, are frequently shaped by systematic deviations from perfect rationality. These predictable patterns, known as cognitive biases, demonstrate that individuals don’t always process information objectively. The framing effect, for instance, reveals that equivalent options presented with positive or negative emphasis elicit different responses, while status quo bias highlights a preference for maintaining current conditions, even when alternatives are demonstrably better. Such biases aren’t random errors; they represent mental shortcuts the brain employs to simplify complex decisions, conserving cognitive resources. While generally adaptive, these shortcuts can lead to suboptimal choices in various contexts, from financial investments to healthcare decisions, suggesting a fundamental interplay between intuitive processes and reasoned judgment.

Despite growing recognition of the pervasive influence of cognitive biases on human judgment, accurately incorporating these nuances into computational models of decision-making presents a formidable challenge. While simple heuristics can approximate certain biases, real-world choices are rarely made in isolation; they involve intricate trade-offs, multiple attributes, and dynamic contexts that confound straightforward modeling. Capturing the interplay between biases – how framing effects might amplify loss aversion, for instance – requires increasingly sophisticated frameworks, often necessitating computational power beyond current capabilities. Furthermore, individual differences in susceptibility to these biases, and the ways they shift depending on expertise or emotional state, add layers of complexity that demand innovative approaches to both data collection and model construction. Progress in this area isn’t merely about achieving greater predictive accuracy, but also about developing tools that can anticipate and potentially mitigate the negative consequences of biased decision-making in critical domains like finance, healthcare, and public policy.

The human mind frequently employs cognitive shortcuts – heuristics – to navigate the complexities of daily life, allowing for swift decisions without exhaustive analysis. While these mental strategies are often beneficial, enabling rapid responses and efficient processing, they are also susceptible to systematic errors that can yield suboptimal outcomes. Research indicates that reliance on these heuristics can lead to predictable biases in judgment and choice, affecting areas from financial investments to medical diagnoses. Consequently, a growing body of work focuses on unraveling the underlying neurological and computational mechanisms that drive these shortcuts, aiming to identify when and why they falter and ultimately develop strategies to mitigate their negative consequences and improve decision-making processes.

The Burden of Thought: Cognitive Load and its Impact on Judgement

Cognitive load, defined as the total amount of mental effort being used in the working memory, directly impacts decision-making processes. When presented with complex information or tasked with demanding cognitive activities, available mental resources become strained. This strain leads to a reduction in the capacity for analytical thought and increases the likelihood of utilizing simplified, often biased, decision-making strategies. Consequently, individuals under high cognitive load exhibit slower response times, increased error rates, and a greater susceptibility to cognitive biases compared to situations where cognitive resources are less burdened. The degree to which cognitive load affects decision quality is dependent on both the complexity of the task and the individual’s cognitive capacity.

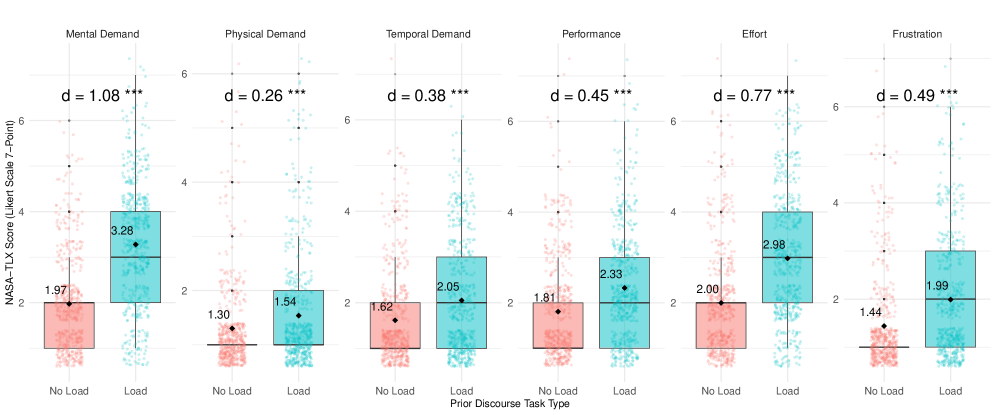

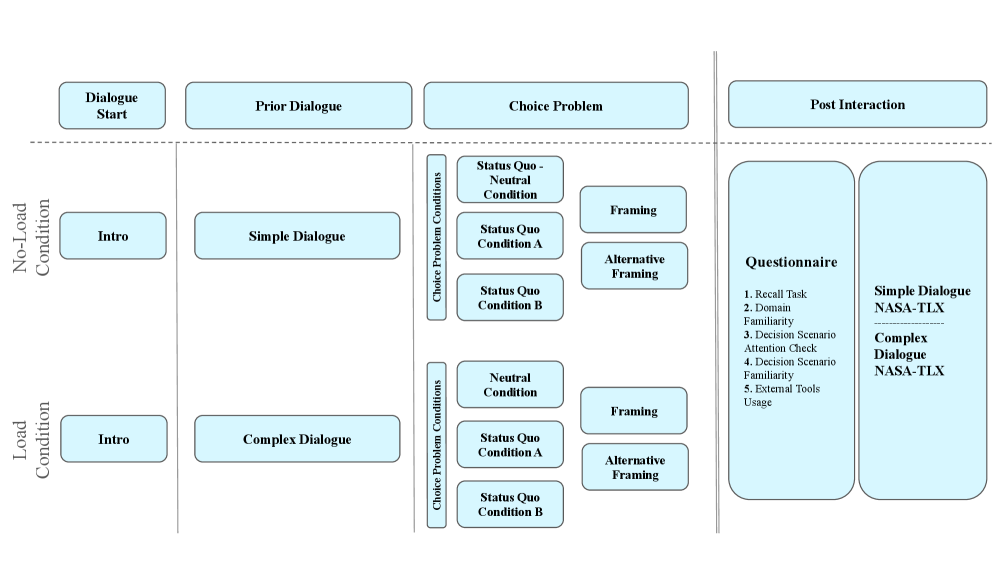

Dialogue complexity was systematically varied to create differing levels of cognitive demand on participants. This manipulation involved constructing conversational scenarios with either simple, straightforward information exchange or complex, multi-layered exchanges requiring greater processing. Cognitive load was not assessed subjectively; instead, the NASA Task Load Technique (NASA-TLX) was employed to obtain an objective, multi-dimensional measure of mental demand, performance, effort, frustration, and time pressure experienced by participants during the dialogue tasks. The NASA-TLX utilizes numerical scales to quantify these factors, providing a composite score indicative of overall cognitive load.

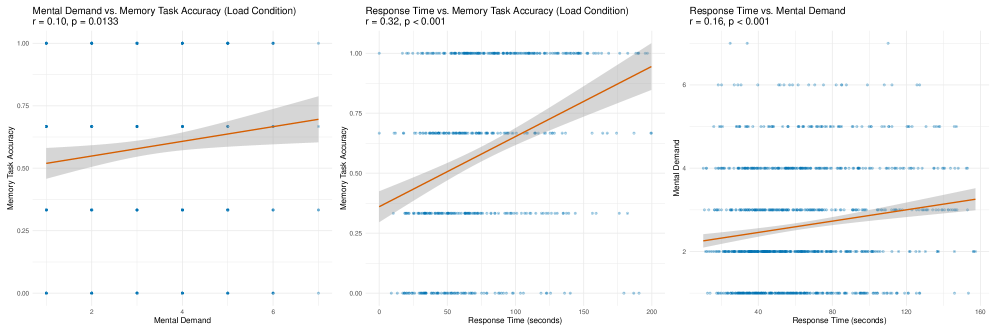

Analysis of user response times revealed a statistically significant increase when participants engaged with complex dialogue compared to simple dialogue; the average response time for complex dialogue was 24.45 seconds, while simple dialogue yielded an average response time of 13.20 seconds. This difference was further substantiated by a Cohen’s d effect size of 1.08, indicating a large effect and confirming that the observed variation in response times is not attributable to chance. These quantitative results provide empirical validation of the hypothesis that increased dialogue complexity correlates with heightened cognitive load.

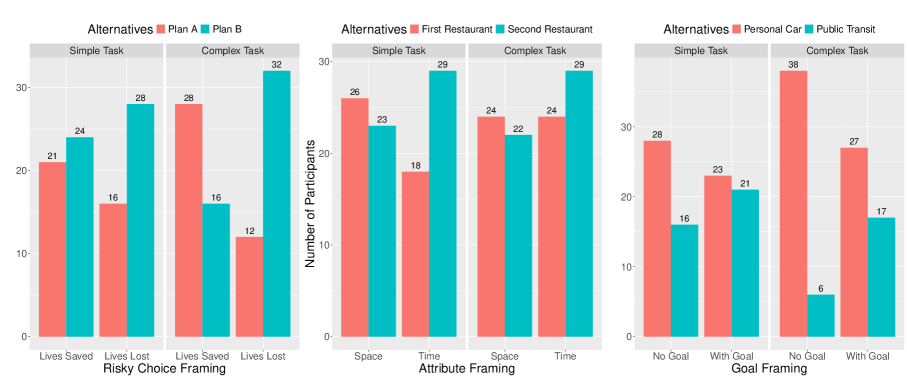

Analysis revealed a positive correlation between induced cognitive load and the application of heuristic biases during problem-solving. Participants exposed to complex dialogue demonstrated a statistically significant increase in reliance on simplifying mental shortcuts, such as availability heuristic and representativeness heuristic, compared to those engaged with simpler dialogue. This suggests that as cognitive resources become strained, individuals are more likely to substitute analytical reasoning with these faster, though potentially less accurate, judgment methods. The observed trend indicates that increased cognitive load does not simply slow down decision-making, but also alters the cognitive processes employed, potentially leading to suboptimal choices.

Mirroring the Mind: LLM Simulation as a Predictive Tool

Large Language Models (LLMs) were utilized to simulate human responses in decision-making tasks designed to assess the impact of cognitive load. The methodology involved prompting the LLM with scenarios varying in complexity, effectively manipulating the simulated cognitive demands placed on the model. The LLM’s generated responses were then analyzed to identify patterns mirroring those observed in human subjects under similar conditions. This approach allowed for a controlled exploration of how increased cognitive load affects choice architecture and susceptibility to biases, providing a scalable and repeatable method for investigating human decision processes without direct human experimentation.

The LLM simulation demonstrated a high degree of accuracy in predicting how cognitive load affects susceptibility to bias in decision-making. Specifically, the model achieved up to 86.4% accuracy in predicting human choices when varying levels of cognitive load were applied. This predictive performance indicates the simulation effectively captures the relationship between cognitive resources and biased reasoning, suggesting its utility in modeling human behavior under pressure or during complex tasks. The simulation’s ability to forecast choices, given cognitive load, validates its capacity to represent the cognitive processes influencing human judgment.

Analysis revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between response length and the time taken to generate a response, as measured by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient ρ = 0.689. This finding indicates that longer responses consistently required more time to produce, mirroring observed patterns in natural human typing and cognitive processing. The correlation strengthens the validity of the LLM simulation by demonstrating that the model’s response generation behavior aligns with established human behavior, suggesting the simulation effectively replicates aspects of human cognitive effort during decision-making.

The demonstrated predictive accuracy of LLM simulation regarding human choice under cognitive load enables the development of targeted interventions. These interventions can be designed to preemptively counteract predictable biases, particularly in high-stakes decision-making contexts such as medical diagnoses, financial analysis, or legal assessments. By identifying conditions likely to increase susceptibility to specific biases, systems can provide decision support – for example, prompting users to consider alternative perspectives, offering additional data points, or adjusting the presentation of information to reduce cognitive strain. Furthermore, the simulation allows for the a priori testing of intervention strategies, evaluating their effectiveness in mitigating bias and improving overall decision quality before implementation in real-world scenarios.

The Foundations of Choice: Recall and the Integrity of Decision-Making

Researchers employed memory recall techniques as a crucial component in dissecting the foundations of participant decision-making. Following exposure to complex choice problems, participants were rigorously tested on their retention of presented information, including details regarding options, probabilities, and potential outcomes. This approach allowed for a direct evaluation of how effectively individuals encoded and stored key data relevant to their choices. By quantifying the accuracy and completeness of recall, the study aimed to determine the extent to which decisions were based on a solid understanding of the available information, rather than being influenced by cognitive shortcuts or biases. The findings from these recall assessments provided valuable insight into the relationship between information processing and rational choice.

Research demonstrates a significant correlation between an individual’s ability to accurately recall details of a decision scenario and their resistance to common cognitive biases. Participants exhibiting stronger memory recall consistently made more rational choices, indicating that robust information encoding plays a crucial role in mitigating flawed judgment. This suggests that cognitive biases aren’t simply errors in reasoning, but may stem from failures in effectively storing and retrieving relevant information during the decision-making process. By strengthening the initial encoding of information – perhaps through techniques that enhance attention or promote deeper processing – it may be possible to improve the quality of subsequent choices and foster more consistently rational behavior.

The development of truly effective decision-support systems hinges on a nuanced comprehension of the interplay between human preferences, the limitations of cognitive load, and the intricacies of memory formation and recall. Current systems often assume rational actors with unlimited processing capacity, a premise demonstrably at odds with observed human behavior; individuals frequently rely on heuristics and are susceptible to biases when faced with complex choices. Future systems must therefore incorporate models of cognitive constraint, accounting for how information is encoded, stored, and retrieved under varying levels of mental strain. By acknowledging these cognitive realities and tailoring information presentation accordingly, developers can create tools that not only offer data-driven insights but also actively mitigate the influence of cognitive biases, ultimately fostering more robust and reliable decision-making processes across diverse applications.

The pursuit of predictive accuracy in LLMs, as demonstrated by this research into conversational biases, echoes a fundamental tenet of efficient system design. The study’s focus on framing and status quo bias under cognitive load isn’t merely about replicating human irrationality; it’s about distilling decision-making processes to their essential components. As Robert Tarjan once stated, “Clarity is the minimum viable kindness.” This research embodies that sentiment – striving to understand, and thus predict, the underlying mechanisms of choice, removing layers of complexity to reveal the core logic. The simplification inherent in modeling these biases offers a path toward more intuitive and predictable AI interactions.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The capacity of large language models to simulate biased human reasoning, as demonstrated, is not itself a revelation. The interesting point resides in the potential for predictive accuracy-a mirroring of irrationality that could, ironically, be harnessed for more rational system design. Yet, the study implicitly concedes a critical limitation: the framing of cognitive load. Reducing complex human thought to a quantifiable variable risks mistaking a symptom for the disease. Further work must interrogate what constitutes cognitive load in these conversational exchanges-is it merely lexical density, or something more deeply rooted in the user’s epistemic state?

The present work offers a foothold, but the true challenge lies not in predicting existing biases, but in anticipating novel distortions. Humans are remarkably inventive in their illogicality. A predictive model, however accurate today, will inevitably be surprised tomorrow. The pursuit, then, shifts from replication to robust generalization-building models that understand the principles of irrationality, not just its manifestations. The goal is not to model the human mind, but to map the boundaries of its predictable failures.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry forces a reassessment of ‘intelligence’ itself. If a machine can reliably predict flawed human decisions, does that demonstrate understanding, or merely a refined capacity for statistical mimicry? The answer, of course, is largely semantic. But the exercise highlights a simple truth: elegance in prediction often arises from acknowledging the inherent messiness of the predicted subject.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11049.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Movie Games responds to DDS creator’s claims with $1.2M fine, saying they aren’t valid

- The MCU’s Mandarin Twist, Explained

- All Golden Ball Locations in Yakuza Kiwami 3 & Dark Ties

- These are the 25 best PlayStation 5 games

- SHIB PREDICTION. SHIB cryptocurrency

- Scream 7 Will Officially Bring Back 5 Major Actors from the First Movie

- Server and login issues in Escape from Tarkov (EfT). Error 213, 418 or “there is no game with name eft” are common. Developers are working on the fix

- Rob Reiner’s Son Officially Charged With First Degree Murder

- MNT PREDICTION. MNT cryptocurrency

- ‘Stranger Things’ Creators Break Down Why Finale Had No Demogorgons

2026-01-20 19:02