“Nothing will die.”

The final scene of David Lynch’s movie, “The Elephant Man,” focuses on the life story of the disfigured performer, David Merrick (played by John Hurt). The film starts with unsettling scenes depicting elephants attacking Merrick’s mother, followed by his birth. Significant moments in the movie, as seen in Lynch’s other works, are portrayed abstractly – for instance, a puff of white smoke represents Merrick’s birth. The film concludes with Merrick completing a sculpture of a cathedral and resting on his hospital bed, mirroring a painting of a sleeping child on the wall. As he lies there, Merrick’s mother appears to him again and says, “Nothing will ever truly die.

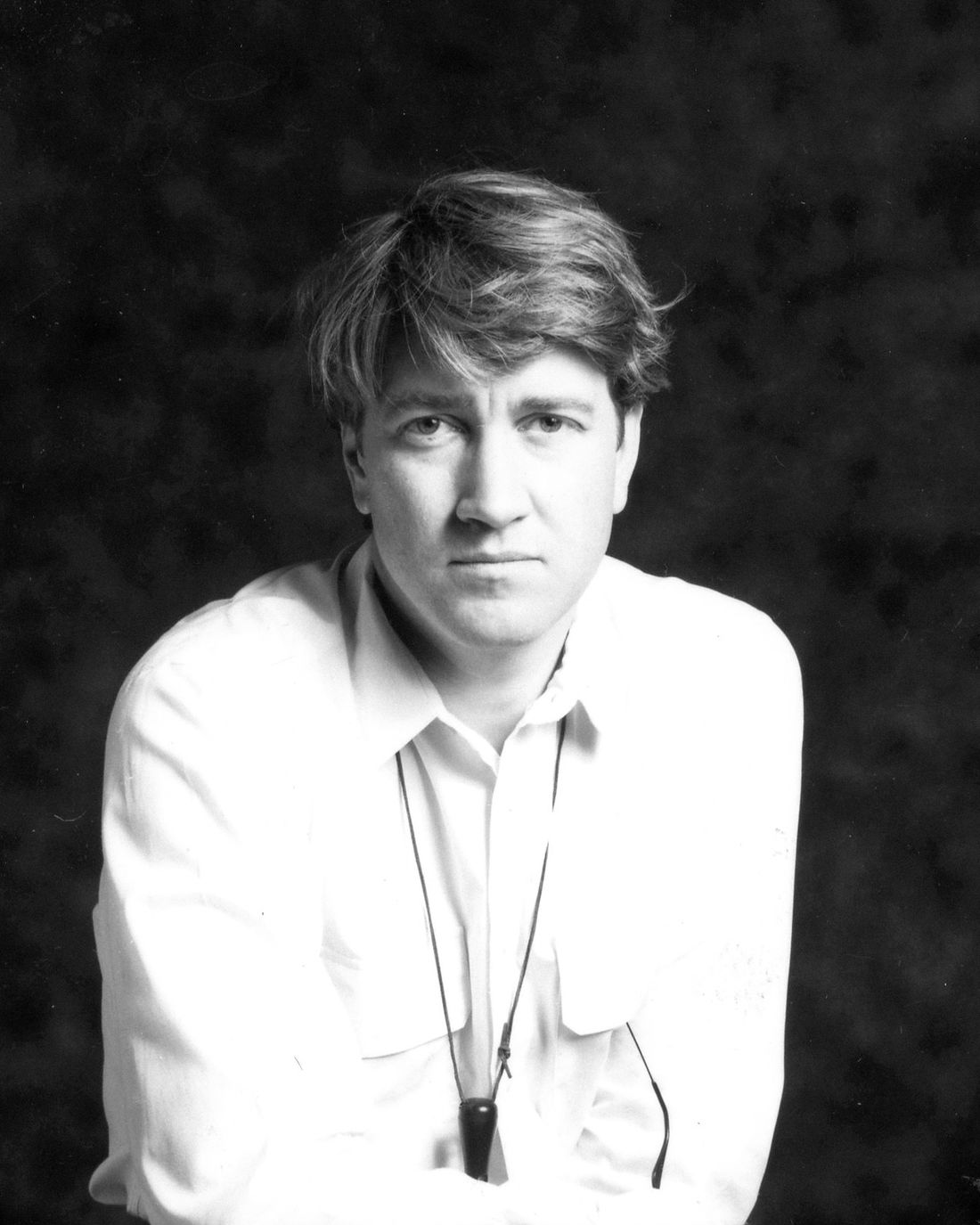

Nothing Will Die,” a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, is a thought-provoking piece that’s worth reading in its entirety on the day Lynch departed from this world, following a lifetime of pondering it. Throughout his creative journey, the native of Missoula, Montana, explored themes of birth, death, and the afterlife, conjuring up other realms and states of existence with such wonder that one can marvel at the vividness of his imagery and the emotions it stirs before delving into the numerous interpretations it suggests. It’s comforting to consider his passing in Los Angeles at the age of 78 as a moment as profound as one of his dreamlike, if somewhat enigmatic, stage settings.

In my perspective, I find myself delving into the world of filmmaking through the lens of David Lynch’s initial masterpiece, the black-and-white 1977 production known as Eraserhead. As the character Henry Spencer, portrayed by Jack Nance, in this movie, I was tasked with a peculiar scene where I expel a translucent, ectoplasmic creature resembling a tadpole-spermatozoa from my mouth. This unsettling image can be seen as a reflection of Henry’s apprehension about fatherhood, but it could also symbolize Lynch’s own concerns regarding the inception of his directorial journey, depending on the response from the audience. Immediately, Eraserhead gained cult status.

Fast forward to 2017 and my collaboration with Mark Frost on Twin Peaks: The Return, where a similar image resurfaces. In this instance, I depict the emergence of an otherworldly creature known as a “frog-moth” from irradiated soil and into a sleeping girl’s mouth. This monstrous birth serves to illustrate the introduction of evil into our world, which is hinted at throughout the work. The detonation of the first atom bomb is also revisited in this series, implying that the event caused a rift in the universe and allowed malevolent forces to enter ours.

The groundbreaking TV series “Twin Peaks” (1990-92), jointly created by David Lynch and Mark Frost, marked a pioneering departure in network television by structuring its narrative around the aftermath of a character’s death – that of troubled prom queen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee). The pilot episode focuses primarily on the shocking discovery of her body wrapped in plastic, followed by the family’s notification and postmortem examination. The protagonist, FBI agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), does not make his entrance until more than half an hour into the show. The raw, intense reactions of the townsfolk to this heinous act – ranging from primal wailing and hysteria to various forms of rebellion – transcended the usual boundaries of broadcast television. This level of disturbance was rarely depicted on TV, a medium that usually omitted or minimized such unpleasantness to avoid overwhelming viewers and disrupting their ability to process commercials. The murder and desecration of Laura Palmer permeated the entire 30-episode run of the original series, even as Agent Cooper and the local police force gradually moved away from this central tragedy to investigate local corruption and personal dramas.

A significant portion of David Lynch’s body of work can be seen as a long-term contemplation on mortality and life after death, yet it never appears that he is solely fixated on this theme. Death is indeed prominent in his works, particularly evident in his collaboration with screenwriter Mary Sweeney on “The Straight Story” (1999). This film revolves around Alvin Straight, an elderly Iowan and long-time smoker who suffers a collapse at home, learns that his brother is terminally ill, and embarks on a 240-mile tractor journey to reconnect with him before one of them passes away.

In many instances, death intruded upon the storyline’s other themes, serving as an unexpected yet impactful reminder of real-world harshness within the otherwise gloomy fantasy realm portrayed in The Return. Some of these moments are quite dramatic and carry significant weight, especially when one is aware of the production details: for example, Lynch and Frost included roles for Miguel Ferrer and Catherine Coulson from the original Twin Peaks cast, both of whom were terminally ill with cancer. Similarly, Stanton, a long-time smoker, also passed away due to heart failure shortly after the series debuted. These actors appear frail in their scenes; among them, Stanton’s character, Carl Rod, manager of the Fat Trout Trailer Park, experiences one of the saddest deaths in the entire series – a hit-and-run accident that claims the life of a young boy, soon after he and his mother were seen playing innocently in a park.

In everything David Lynch directed, there’s an underlying theme of death and the unknown that follows, even when the specific works seem to focus on other topics. For instance, his 1984 adaptation of Frank Herbert’s book Dune, tells the story of a messianic figure from another world whose family suffers great loss and is believed dead. However, he is reborn as the leader of a rebellion on a desert planet after consuming a substance that grants mind-bending, reality-distorting abilities. Similarly, Lynch’s career-defining film Blue Velvet, which introduced audiences to Kyle MacLachlan as the amateur detective and peeping tom Jeffrey Beaumont, begins with the hero’s father suffering a stroke while watering the lawn, symbolizing what occurred within his circulatory system. The looming possibility of the father’s death casts a shadow over the entire narrative, driving Jeffrey to delve further into the darkness and depravity he was previously unaware of.

As a devoted cinephile, I can’t help but reminisce about the electrifying duo of Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern) in David Lynch’s masterpiece, “Wild at Heart” (1990). We’re talking about a pair of runaway lovers who are constantly eluding assassins sent by Lula’s formidable mother (Diane Ladd), a character reminiscent of the Wicked Witch of the West, given Lynch’s frequent references to “The Wizard of Oz” in his filmography. This movie is filled with characters fleeing death, the specter of death, or the emotional scars left by events that extinguished their spirits. Despite being propelled by passion, love, and youthful defiance, the specter of the end lingers over the narrative, culminating in a chilling scene where our dynamic duo stumbles upon a car accident site. As Film Comment’s Kathleen Murphy eloquently put it: “Lula and Sailor stumble upon Death’s construction site in a sequence that showcases Lynch at his hallucinatory finest. Spectral garments flutter along a moonlit highway. A maimed figure materializes in and out of the headlights of an overturned car. A girl, disheveled and lifeless, laments losing her purse to her mother who will supposedly kill her. Death reveals its visage, its mouth filling with blood.

In his defiance against fading creativity, David Lynch’s storytelling evolved into progressive narrative innovations. This transformation began in 1992 with “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me,” a theatrical prequel to the original series, rated R. Instead of following the usual trajectory, this film delved into Laura Palmer’s final days, a period marked by rape, torture, and ultimately murder. The narrative was fractured, occasionally raw and candidly naive, more violent, sexual, and undeniably peculiar than the series had ever dared to be. Contrary to popular belief, it didn’t receive boos at its Cannes premiere, though there might have been some negative reactions during press and critic screenings. However, due to its unsettling nature, it failed to meet expectations of those seeking a precursor to what is now known as “fan service.” For those unfamiliar with the show, it was bewildering and upsetting, leading to poor box office performance and effectively diminishing Lynch’s status that Time magazine had elevated 18 months prior.

Fire Walk with Me was later appreciated by a new generation of viewers and critics as potentially Lynch’s most visually daring film since Eraserhead, marking the beginning of a fresh era in his career. Each subsequent movie appeared to be an intense challenge to the concept that conventional storytelling could provide insight into life. It felt like Lynch was attempting to achieve with cinema what he suggested for artists using transcendental meditation and other mind-expanding techniques: encouraging people to question their preconceived notions, realizing that the established principles and structured rules, which have been enforced throughout our lives in both reality and art, are essentially meaningless deceptions. A higher and more potent truth can be accessed by discarding or breaking these conventions.

1997’s “Lost Highway” presents a circular narrative reminiscent of a Möbius strip, where a character portrayed by Bill Pullman morphs into another (Balthazar Getty) and becomes entangled in an endless cycle of love for the same woman (Patricia Arquette), who appears in different manifestations. The characters seem trapped in a perpetual purgatory instead of experiencing life or death.

“Mullholland Drive” (2001), originally conceived as an abandoned TV pilot, was not just Lynch’s critique of Hollywood, but also an exploration that questions the boundary between reality and illusion. The movie delves into dreams within dreams, where one dream bleeds into another, portraying life as a collection or sequence of dream-like situations.

In contrast, “The Straight Story” (1999) is a tranquil, leisurely drama devoid of perversion, violence, sensuality, psychedelic elements, and abstract concepts. Upon reflection, it appears to be Lynch’s farewell to traditional storytelling techniques that have been prevalent in American cinema since its inception.

“Inland Empire” (2006) revisits Hollywood through the deteriorating mind of a film actress (Laura Dern, who might be one of Lynch’s most significant muses). This film is characterized by its fluidity, where nothing remains constant and everything transforms. The story seems to disintegrate as the movie progresses, much like the state of being experienced by Kyle MacLachlan’s character in “The Return.

David Lynch’s portrayal of death and mortality extends far beyond the typical boundaries of American commercial films. Unlike regular movies that might momentarily interrupt a romantic comedy with a minor character’s funeral, or use the violent demise of a loved one as a catalyst for an action film, Lynch approaches death in a more reverent, poetic manner. He views it as a startling disruption to our subconscious routines, which we often neglect to ponder upon, and transforms each occurrence into a form of audiovisual poetry. If you were to compile every scene of Lynch’s work that deals with birth, death, and transformation, you would essentially create a collection of elegies.

Although David Lynch’s films are marked by illness, injuries, and concluding moments, they are far more than just these aspects. They brim with humor, quirkiness, music, vibrant colors, and unexpected detours that one can never fully encapsulate in their ailments and final bows. As stated on his official Facebook account by his family, “There’s a significant void left in the world now that he’s gone. But, as he would say, ‘Focus on the donut, not the hole.'” Donuts held a special place for Lynch; they were omnipresent in the original Twin Peaks, alongside coffee, pie, and cigarettes, which formed the four essential food groups in his life. Cigarettes, which he smoked with unparalleled coolness among directors, were also a part of his life, leading to emphysema diagnosed in 2020. He was forced to quit smoking due to health complications, later announcing that he required supplemental oxygen and had mobility issues, preventing him from directing films on location. He prepared fans for the likelihood that The Return might be his last directorial credit, but not his final project altogether.

Lynch is a Transcendental Meditation practitioner who wrote a combination memoir and self-help book titled Catching the Big Fish (2006). The title is a metaphor for increasing one’s capacity for artistic inspiration by expanding the mind and going deeper into the subconscious. “”ideas are like fish,” he wrote. “If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper.”

Read More

- INJ PREDICTION. INJ cryptocurrency

- SPELL PREDICTION. SPELL cryptocurrency

- How To Travel Between Maps In Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- LDO PREDICTION. LDO cryptocurrency

- The Hilarious Truth Behind FIFA’s ‘Fake’ Pack Luck: Zwe’s Epic Journey

- How to Craft Reforged Radzig Kobyla’s Sword in Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- How to find the Medicine Book and cure Thomas in Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- Destiny 2: Countdown to Episode Heresy’s End & Community Reactions

- Deep Rock Galactic: Painful Missions That Will Test Your Skills

- When will Sonic the Hedgehog 3 be on Paramount Plus?

2025-01-17 04:54