As a storyteller and an observer of human experiences, I find myself profoundly moved by the rich tapestry of life that unfolds through the life of this extraordinary individual. The interweaving of his acting career, family heritage, and personal growth forms a narrative as compelling as any scripted drama.

Adrien Brody paused to consider a heap of cardboard boxes while strolling through London’s West End, where he is performing in a play. Upon seeing several dilapidated boxes scattered on the sidewalk, he remarked, “This could be an excellent breakdancing stage or a treasure trove! It’s also like a little community.

In our brief time together, I’ve come to understand that Brody’s thoughts are a fascinating dance between seemingly disparate ideas. Just moments ago, the sound of a mailbox closing reminded him of a line from his play, The Fear of 13, as his character, a death-row inmate, received a letter. This triggered memories of his own scuba diving adventure at age 23, an unlicensed dive that took him back to the night before he left Guadalcanal, where he was filming Terrence Malick’s war movie The Thin Red Line. He explains, “I had spent six months playing a man grappling with his inadequacies due to fear. So, I dove into the sea to survey the wreckage of sunken Navy ships from the Pacific War to prove that I wasn’t cowardly.” He admits, “That was me being reckless and youthful.

Oh right, the cardboard.

In Guadalcanal, numerous locals resided in houses constructed from cardboard boxes. This stack of boxes brought back memories for him, specifically an interaction he had with a young boy there. During one of his outdoor hip-hop performances with his co-star, Dash Mihok (who they called the Thin Red Liners), a child approximately 8 years old approached Brody and asked if he could buy him a coconut. After fulfilling this request, they struck up a conversation. When inquiring about the boy’s absence from school, he shared that his uncle made him collect boxes for shelter during the day. Touched by the situation, Brody agreed to pay the boy several hundred dollars yearly so he could attend school. Inspired by this act of kindness, his co-star Mickey Rourke (who was later edited out of the film) also contributed to funding the boys’ education until they completed high school. “I had forgotten about that story for a long time,” Brody reflects, “but looking at that stack of cardboard boxes, it’s like digging ten stories deep into the past.

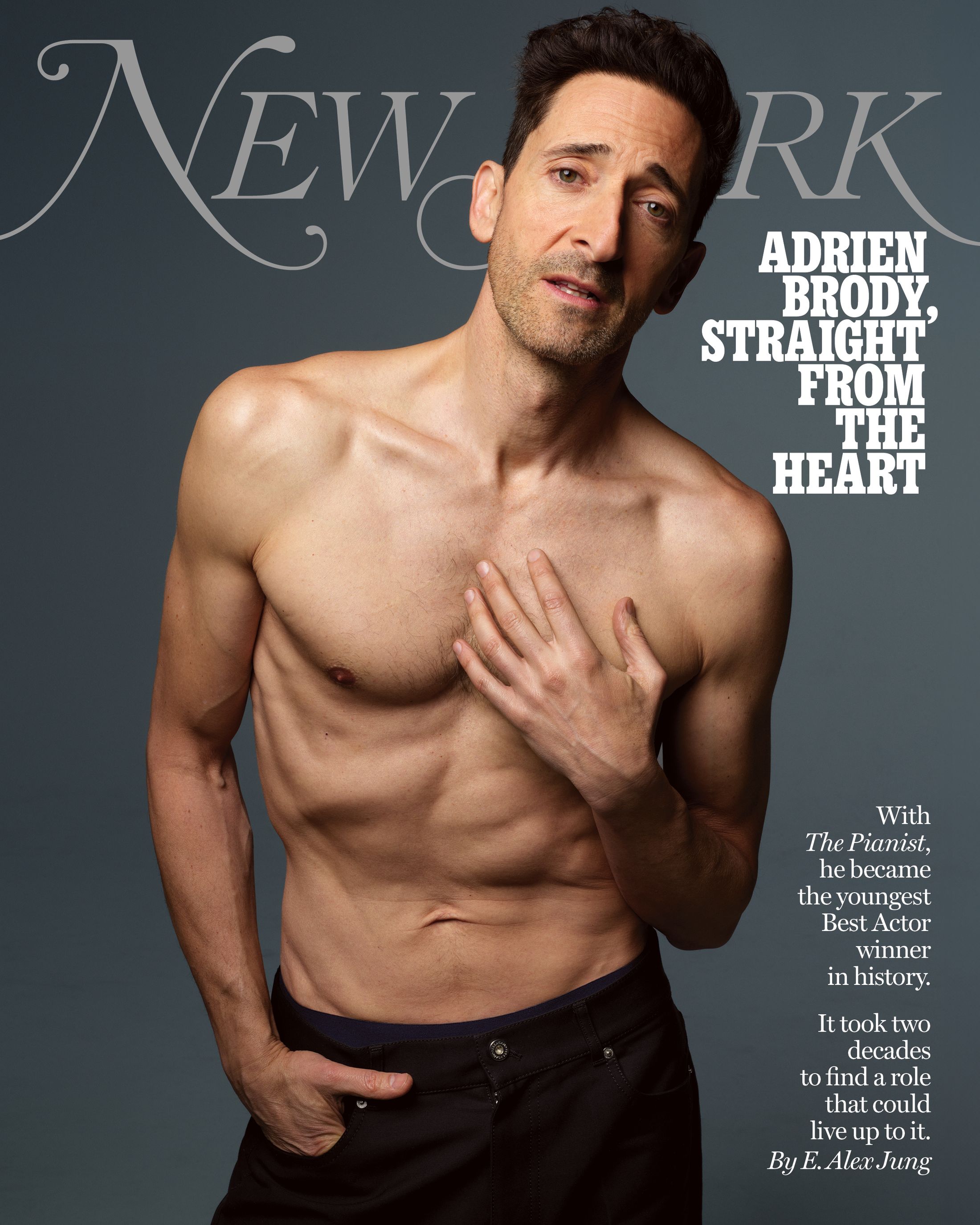

In This Issue

Adrien Brody

Currently, Brody is 51 years old and maintains a naive charm that might surprise some people. Unlike others who prefer short, catchy phrases, Brody tends to be deep and sincere in his conversations, much like an unleashed dog roaming freely. His thoughts wander, often leading discussions on tangents before circling back, making for captivating yet meandering stories. This trait might account for the fact that despite his exceptional acting abilities, he has not fully embraced fame. His girlfriend, designer Georgina Chapman, frequently remarks that Brody struggles to convincingly hide his dislike towards people or things. “She tells him, ‘You’re an actor, darling. Why can’t you?'” To which he responds, “It’s very challenging unless I put in effort to genuinely believe it.

Since 2003, when Adrien Brody clinched the youngest Best Actor Oscar at age 29 for Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist,” he has felt distinctively out of sync with ordinary time and space. His European sex appeal, characterized by a chiseled profile reminiscent of a cliffside and expressive angled eyebrows that would have moved Rodin to tears, set him apart. After winning the Oscar, Hollywood struggled to find suitable roles for Brody, often comparing him to Robert De Niro and Al Pacino but never offering parts in their vein. (One can only speculate how a young Brody might have thrived in today’s industry of ethereal leading men.) Aware that he doesn’t appeal to everyone due to his demeanor, bearing, and gravity, Brody acknowledges his unique identity. He admits, “I embrace what I am and who I am.” He understands that being generic can lead to more opportunities in the leading man category, but it is the uniqueness of character that truly captivates us, making humans fascinating.

In Brady Corbet’s movie titled “The Brutalist“, Brody portrays László Tóth, a rigid artist struggling in an unforgiving era. The story unfolds as Tóth, a Hungarian architect educated at Bauhaus and a Holocaust survivor, lands in the United States in 1947. He departs from his life in Budapest, where his architectural masterpieces shaped the city’s skyline. Upon arrival in Philadelphia, he takes up work at his cousin’s furniture shop, where his modernist designs, reminiscent of Marcel Breuer, clash with local tastes. Over time, he gains the attention of Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a domineering industrialist, who wants him to construct a community center in Doylestown on a picturesque hillside. Here, their ambitions collide.

In this scenario, Tóth faces challenges as Van Buren’s impulsive decisions threaten his artistic vision for the project, but he perseveres to maintain their patron-artist relationship. The process is marked by delays, unexpected expenses, and skepticism from townsfolk; Tóth forgoes his pay to stay faithful to his artistic ideals. A well-known architect, notorious for building shopping malls, is controversially brought in as a consultant, infuriating Tóth. Despite being single-minded, Tóth can also be rude, petulant, warm, and humorous; he’s plagued by his past. Corbet describes The Brutalist as a film about the process of making a movie, making it easy to relate Tóth’s struggle to the act of filmmaking itself. The Brutalist showcases an expansive narrative, filmed in VistaVision with a 3.5-hour runtime and a 15-minute intermission. Corbet navigated his own seven-year odyssey to reach this stage, initially halted by the pandemic when he had a different cast, then rebooting the project with a new team of actors. Tóth mirrors Corbet, Brody, and any artist striving to create something uniquely theirs.

Engaging with such a profound project serves to remind Brody of life’s transience and the legacy he wishes to create. “The Brutalist” rekindles our appreciation for Adrien Brody, whose visage carries the burden of history, sculpted for grand narratives that delve into art, immigration, and conflict.

I encountered Brody for the first time following a nighttime presentation of “The Fear of 13” at the Donmar Warehouse in November. He portrayed Nick Yarris, a genuine person who was falsely accused and spent 21 years on death row from 1982. After the show, Brody was dressed casually in a gray sweater and sweatpants; his hair was still wet from a shower scene. Upon my arrival at his dressing room, he greeted me with a warm embrace, expressing, “I’m glad to share whatever I can with you.” His agent Ben Dey was present, along with Chapman. Brody and Chapman had become acquainted in 2019 through a mutual friend during a trip to Puerto Rico. “She convinces me of most things,” Brody shared, including this play. Since there was a matinee earlier, he had been at the venue all day. “This is my mini-prison,” he said, gesturing towards the blue cot on the floor. He seldom goes out, opting instead to eat meals from home. After the matinee, he would meditate and take a nap. When it was time to gear up for the second show, he’d consume caffeine, take lion’s-mane mushroom supplements, and do push-ups while listening to trap music. To wind down, he’d switch to something melancholic and slow (today that was John Frusciante’s “The Will to Death”).

In his professional theater career, Brody’s latest production, “The Fear of 13”, marks a significant milestone since he was 12, when he starred in Joan Schenkar’s play “Family Pride” at Theater for the New City in the 50s. He bore an immense burden to make this performance successful. Throughout the opening week, his mind often wandered to Iwao Hakamata, a Japanese man who was recently released after spending 58 years behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit. Collaborating closely with playwright Lindsey Ferrentino, they both discovered a shared quirk of adding “ass” as a suffix, such as dumbass or smug-ass. During the rewriting process, Ferrentino adjusted the dialogue to better reflect Brody’s style, bridging the gap between their visions for the play and character. As Ferrentino puts it, “There was no gap in understanding what this play and character were supposed to be compared to his perception.

In this compact, 251-seat black-box theater setting, Brody truly shines. Similar to his performance in “The Brutalist”, he masterfully portrays a man’s life journey, injecting Yarris with an infectious blend of charm and wit. The play takes us on a rollercoaster ride, from moments where we see him as a troubled teenager, engaging in dangerous activities like drug use and car theft, to scenes where he crumbles under the weight of the legal system’s labyrinthine bureaucracy.

Outside of his job, Brody leads a transient lifestyle as he claims. In London, however, he’s been living a solitary life reminiscent of a monk. Upon arrival, he resided in an attic apartment within the Donmar’s rehearsal space for a month. His mornings started with stretching, followed by a trip to the basement for work. Afterward, he would either take a walk or swim, then revisit his lines. On Sundays, he was the only occupant and occasionally triggered the alarm upon leaving. Once the performance began, he rented an apartment in Islington.

A few days after my visit to Brody’s place, I find him dressed casually in a white T-shirt and jeans, with incense in hand. He ensures the room is comfortably warm, and we descend to the garden level. There, he prepares us some fragrant green tea while we sit on the floor around a stone coffee table that he describes as “Brutalist.” He then lights up copal, places it carefully on a fork, and offers dried mango. A window above us allows pedestrians to be seen passing by. The air is filled with a pleasant, earthy aroma. As we chat, a figure silhouetted against the window shade, using his phone, momentarily catches our attention. “Where’s my camera?” Brody queries, looking up. “Damn it, it’s too late.” The man has moved on; the fleeting moment is lost.

Brody believes in always being prepared, much like his mother Sylvia Plachy who carried five cameras with her for the same purpose. This mindset applies to his own work as a cinematographer, where he ensures he has the necessary tools to tackle any issues that may arise on set – mechanical malfunctions, time constraints, diminishing light, unexpected sounds. In a way, he views his role as a chronicler of time, capturing fleeting moments in film so they can endure through future generations. Occasionally, the opportunity to seize the perfect moment might only last a few minutes. As Brody puts it, “The ability to find that one instant amid the 15 minutes you have to truly capture it, knowing that if I didn’t uncover it within that timeframe means it was never discovered – it will never be discovered, it will never be something we can reclaim.

In the pursuit of authenticity, dedication, discomfort are all means to seize the essence of a moment. During the filming of “The Jacket,” a science fiction thriller where he was confined to a mental institution, he requested to be kept in a straitjacket for a more realistic experience. An unintended blow during the shooting of “Summer of Sam” led to a broken nose, leaving him with a permanent dent. For “Oxygen,” where he portrayed a serial killer with braces, he opted for real metal ones rather than prosthetics. As he put it, “I didn’t realize how excruciatingly painful that was until they yanked them out with pliers from my teeth at the end.” For “Wrecked,” he consumed ants and worms (his character finds himself alone in the wilderness).

For no film did an actor endure as much physical hardship as “The Pianist.” Six weeks before filming in Germany, he discarded all his worldly goods, selling his car, giving up his apartment and phone, and storing his belongings. The movie was shot backwards, starting with Szpilman at his most emaciated. Brody subjected himself to a near-starvation diet, consuming minimal protein while practicing Chopin for long hours. He lost 30 pounds, dropping to 129. His relationship ended. By the time shooting began, he was barely drinking water. “That was a physical transformation essential for storytelling,” he says. “It also led me, spiritually, to a profound understanding of emptiness and hunger that I had never experienced before.

The impacts lingered significantly. He developed sleep issues and panic attacks. I inquire if he thinks he might have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) from the event. “Yes, I do,” he replies. “For at least a year, I struggled with an eating disorder. And for a year, I felt deeply depressed, though jokingly I say it’s been a lifetime. But don’t worry, I was just jesting.

In approximately an hour, Brody will attend an acupuncture appointment in a rehearsal building, so we’re off to catch the subway. He starts sharing his story about riding a gas-powered scooter, a GoPed, to attend the premiere of his movie “Restaurant” at Lincoln Center. As he shows me the photo on his phone, we accidentally miss our stop. We get off and retrace our steps to head in the right direction. I inquire about his feelings regarding returning to the whole Oscar awards spectacle. He pauses thoughtfully. We’ve now reached our destination. “Ah, you caught me off guard with that question and then we missed our stop,” he says. “A more pertinent query might be: if it does happen again, how can I learn from my past mistakes to expedite the process of being recognized for truly significant works?

Following the successful debut of “The Pianist”, Brody took a break from work for nearly a year, according to his father Elliot Brody. Elliot explains that it wasn’t a self-imposed hiatus, but rather due to the fact that despite winning an Oscar, Adrien was not offered roles that matched his recent accomplishments. Consequently, he declined several poorly written parts. Adrien himself acknowledged the high expectations placed upon him, stating, “I must admit the bar was set quite high.

Over the coming years, Brody found himself collaborating with prominent filmmakers: he worked with Peter Jackson on “King Kong”, Rian Johnson on “The Brothers Bloom“, M. Night Shyamalan on “The Village“. His collaboration with Wes Anderson began with “The Darjeeling Limited” and continues to the present. He starred in “Predators“, a 2010 reboot of the franchise. Initially offered the role of Edwin, an out-of-place doctor among professional killers, he desired to play Royce, the rugged, silent mercenary and leading man. Unhappy with this role, Brody wrote a polite letter to producer Robert Rodriguez suggesting he could play the protagonist instead. “I suggested, ‘There are many paths you can take. One is obvious, but this isn’t it.’,” he recalls writing. “If you flip open Time magazine and see soldiers, they don’t look like Schwarzenegger or dissimilar to me. It’s about emotional and intellectual toughness.'” He successfully persuaded Rodriguez, who in turn convinced the executives at 20th Century Fox to agree to his request.

Trying to reinvent himself as suitable for the role of Royce, he aimed to shift people’s views about him. However, his comedy projects didn’t fare too well. He tried his hand at unconventional roles such as Psycho Ed, a drug dealer, in the film “High School” and Flirty Harry, a police officer with a penchant for using gay innuendos, co-starring Lindsay Lohan in “InAPPropriate Comedy”. These comedies earned less than $250,000 and were poorly received, receiving only a 1 out of 100 on Metacritic. He admits that he had thought he wanted to delve into comedy, but this was another constraint as he had mainly done dramatic work before, and people didn’t believe he could be funny.

In the year he received an Oscar, Brody took charge of Saturday Night Live. He made quite an entrance as host by sporting a wig with dreadlocks and adopting a lively Jamaican accent while introducing musical guest Sean Paul. He arrived that week brimming with ideas, one of which he pitched enthusiastically. “Everyone was speechless from my proposal,” he recalled. However, it was SNL who provided the costume for the skit, and it was performed during the dress rehearsal. “I believe Lorne wasn’t thrilled with me adding extra elements to the bit, but they let me do it,” he said. “Strangely, I thought that was a permissive environment to experiment.” There were whispers that he had been barred from the show, though he claims this is just a rumor. “But I’ve also never been asked back since then,” he laughed, implying uncertainty about the matter.

Brody has become more cautious and reflective when it comes to his words, particularly regarding his past celebrity incidents. He seems uncomfortable discussing his spontaneous kiss with Halle Berry during the Oscars, and prefers not to speak about it. The political subject is also sensitive for him. The storyline of “The Brutalist” coincides with the establishment of Israel, and some characters in the movie decide to move there. Brody won an Oscar a few days after the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, and during his speech, he prayed for peace. This awards season coincides with ongoing conflicts in the Middle East involving Israel, and when asked about the situation in Gaza, he gives a diplomatic response, expressing opposition to injustice and sympathy for those affected by global conflicts that are beyond our control.

During the 2010s, a series of missteps in his career started piling up: His films weren’t successful financially. “I prefer not to delve into specific movies that I deemed failures,” Brody shares with me, but he explains that he consistently applied the same criteria to scripts: “Is it unique? Do I appreciate the director? Will this be rewarding?” He took risks with new directors, such as Michael Greenspan for the thriller Wrecked, where he portrays an unnamed crash survivor. Critics would argue that he delivered an exceptional performance in a mediocre film. (“Brody’s dedication to the material keeps Wrecked from collapsing,” Eric Kohn wrote.) He ventured into the Chinese market with Dragon Blade, starring alongside Jackie Chan and John Cusack. What he discovered during this period was that “you don’t have the artistic freedom to experiment as much in an industry with established rules. I was unaware of this, and it still doesn’t fully register.

Experiencing the burden of the commercial aspect of Hollywood, he realized that an actor’s worth often hinges on their box-office earnings. He explained, “When there is money involved in a production, they always have lists.” The implication being, you either make the list or you don’t. If your films tend to earn profits, you’re ranked high on that list. Conversely, if you focus more on artistic, less mainstream projects, you’ll find yourself at the bottom. To maintain an A-list status, one must deliver profit, which leads him to worry about this potential degradation of values affecting him not just professionally, but also deeply personally. Not merely, “Did I make a bad movie?

Over time, Brody found himself feeling a sense of wear and tear. Around 2018, he decided to take some time off. He reconnected with one of his earliest passions and started creating art once more, blending techniques reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg and Jackson Pollock. “I simply took a step back,” he admits. “It was necessary for me to find balance.” After being away for a while, Chapman encouraged him to return. She explained that isolating himself and painting wasn’t the answer, even though it might seem like it. So, gradually, he came back, making appearances on shows such as Succession and Poker Face, and continuing to be part of Wes Anderson’s cast. “She helped me understand that it would be a shame to let my frustrations hinder me from pursuing what I was meant to do with an open heart,” he says.

In 2019, during a break, Corbet first encountered Brody for a chat about “The Brutalist.” Later on, Corbet chose Joel Edgerton for the project. However, production came to a halt due to COVID-19. When filming resumed, Brody was back involved. Corbet remarked, “Our initial conversation somehow stuck with me. I hadn’t found anyone else who grasped the film as thoroughly as Adrien did. It’s not many who possess the background and understanding that he has.

One factor that resonated with Brody in the movie was its connection to his mother’s background, as the story is set in Budapest where her mother was born. Brody’s maternal grandparents were Jewish and most of them perished in concentration camps during the Holocaust. This personal history significantly influenced Brody’s portrayal of Lázsló Tóth in the film, which continues the narrative from “The Pianist.” Lázsló has survived the camps but bears the weight of his past experiences. He grapples with his estrangement from his wife, Erszébet (Felicity Jones), and distances himself when they reunite; he engages in infidelity with a woman at a brothel, turns to heroin for self-medication, and Corbett aimed to portray Lázsló as challenging the notion that one can only empathize with someone who has endured great trauma if they are inherently good.

In my perspective, the intensity of “The Brutalist” was significantly less compared to “The Pianist.” While “The Pianist” took six months to create, “The Brutalist” was filmed in a much shorter span. As Brody expresses, “The Brutalist” challenged the belief that prolonged suffering is essential for creating a character, which came as a surprise to me since I didn’t feel compelled to carry so much personal anguish off-set. There’s a particular scene in the movie where Tóth is drawing an institute while eating an apple, and when we called cut, Adrien wasn’t finished yet, lost in his art. It wasn’t Method acting per se; it was simply Brody, the artist, enjoying a peaceful moment under the sun.

In December, Brody takes me along to visit his parents who reside in Woodhaven, Queens. Coincidentally, this is the same day he receives an award from the New York Film Critics Circle. His play has recently closed, and he’s now fully immersed in awards season – a demanding period when deep thoughts can easily be sidetracked. “I don’t want to entertain questions like ‘This is a precursor to the Oscars…’,” he states, “I’m too serious about it, and I know I am.” He cherishes every moment with his parents; they took him to an awards ceremony the previous night, and they will drop him off at the airport for his flight to L.A later in the evening. The house they live in is where he grew up, a white single-family home with a driveway where he used to build muscle cars. They moved there from Jackson Heights when Brody was 4 years old, around the time that his mother, a photographer for the Village Voice, received a Guggenheim fellowship. His father, a retired schoolteacher with a background in philosophy and social sciences, taught middle school in Jackson Heights. Brody bears a resemblance to both of his parents.

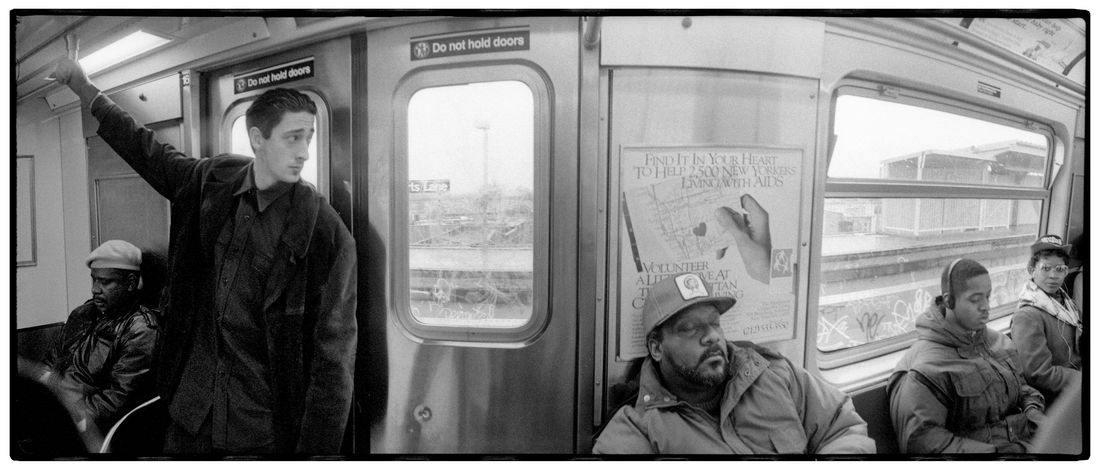

During our ride, he narrates his childhood experiences, echoing a city-dwelling Huckleberry Finn. He enjoyed spending time with the older kids. In Forest Park, they’d slide down steep slopes on car hoods and made fishing lines from dental floss and safety pins, using dough as bait to catch fish in the ponds. They often watched double features at a theater called the Drake, where his father once caught him smoking cigarettes in the front row. It wasn’t always easy though. He was beaten up for sporting a rattail hairstyle. A friend he knew in the fourth grade was shot over a gold chain. “Looking back, it’s shaped me into who I am,” Brody remarks as we step out of the car and stroll along Jamaica Avenue. “New York is tough. It’s molded me into a reactive person in a way I don’t always appreciate, but it seemed necessary at that time.

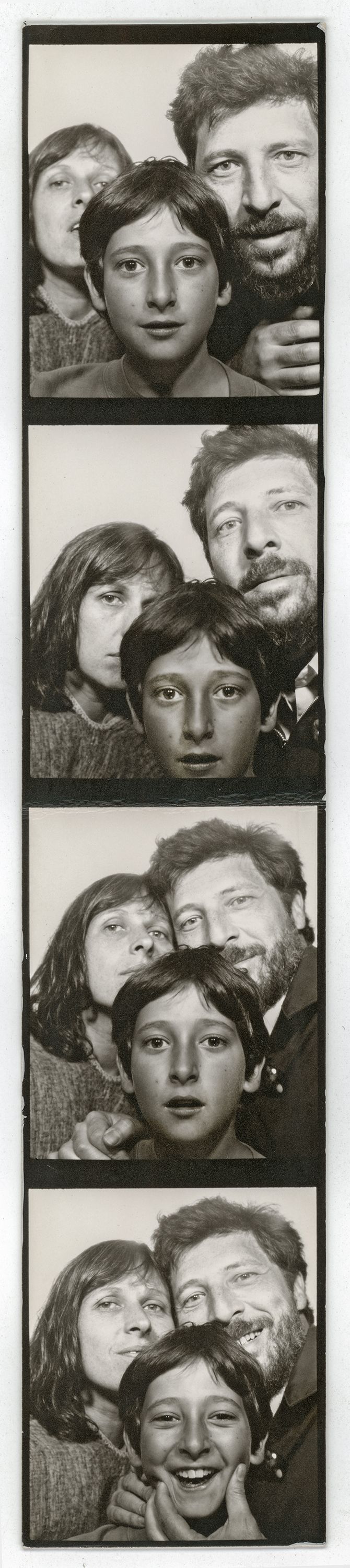

As we head towards his family’s home, he phones them to check if it’s fine for us to drop by. Upon our arrival, his mother is feeding some strays in the backyard while his father is cleaning and drying Tupperware containers in the dishwasher. They welcome me with a fresh cup of coffee and give me a tour of their home. The walls are adorned with artwork and family photos, including pieces by both Brody men. His parents have been together for 62 years, and he is their only child. On the living-room mantelpiece rests his Oscar. Plachy shows me pictures she’s taken of him throughout the years. When he was an infant, she created comic strips about his amusing remarks. She used to joke with friends that she would one day compile these photos into a book. (She hasn’t done it yet, but plans to.) She reminisces about people asking her, “Who will be interested in your little boy growing up?” She chuckles, “Little did they know!

As a child, Plachy often brought Adrien with her to work assignments, such as gallery openings or photographing Jorge Luis Borges. Even when he grew older, he continued to accompany her. They visited the World Trade Center the day after 9/11 together. Through observing her work, he learned to be mindful and attentive. “You see things in a way that most people don’t,” he said to her. “You were always focused and present. And I spent so much time with you, watching closely. That’s why I became more focused and present myself.

At age 12, he started acting in weekend courses for kids at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He soon landed an agent and secured several theater roles within the city. Even at a young age, he seemed drawn to serious themes; his debut film was “Home at Last” on PBS, where he portrayed a New York City orphan adopted by a Nebraskan farm family, partially for labor purposes. His parents have accompanied him on shoots across the globe, such as those for “The Brutalist,” in which his mother took photos. In her book titled “Self Portrait With Cows Going Home,” there are images of him during the production of “The Pianist.” She writes, “He was a reflection of my father at a young age.” “It’s both exhilarating and unsettling when your own son can summon spirits,” she adds.

In the film “The Brutalist“, Brody’s way of speaking resembles Plachy’s father, who had a thick Hungarian accent when speaking English. Unfortunately, Brody’s grandfather passed away when he was only 7 years old, but the memories of his speech and mannerisms stayed with him. Lázsló’s voice was crucial for him to portray accurately. He collaborated with a dialect coach and listened to how Hungarians from that era spoke. “I knew when it felt authentic and when it didn’t,” he explains. “The Hungarian character’s sensibility, sensitivity, and strength – qualities beyond language – were noticeable to me in that role.

In “The Brutalist,” when Brody discusses his role of representation, it signifies this specific house inhabited by two individuals, encompassing their family history that led him to this remote location, away from corporate deceit and glamorous spotlights. As the winter day ends, before I depart, Brody, seated on a modest couch in the living room, narrates a tale. During “The Fear of 13,” he recalls having a keen awareness of time, knowing exactly when the program surpassed its three-minute limit. Towards the end of his stint as Nick Yarris in the series, Brody challenges the conventional boundaries by directly addressing the audience through his final monologues. At times, the intensity becomes overwhelming and viewers look away. However, others provide him with the encouragement he seeks.

He discovered that allowing emotions to pass freely within him enabled him to manage them much like a tap. “That’s when I truly feel alive, when you’re connected and merely adjusting the flow and intensity of those feelings,” he expresses. In his last speech, Nick reminisces about a beautiful sunny day when everyone was outside, unaware of an approaching storm. This scene serves as a metaphor for the pure, carefree childhood that exists prior to a life-altering event, like what happened to him. As Brody recites the closing passages of the play, he mentions the lines where the sky becomes overcast and no one had thought to bring an umbrella: “We all find ourselves on the brink. We gaze up at the heavens together… hoping it will never rain…

During peak performance, he managed to suppress his tears until they dropped at the final word, just before the stage lights dimmed and the music reached its climax. This rare moment, perhaps occurring only one or two times throughout the entire play’s run, was instrumental in helping him grasp why actors choose theater. Unlike movies that can be paused and rewound, the ephemeral aspect is what makes it special. “To perform for an hour and 47 minutes, only to have complete control over a genuine emotion within you at exactly the one hour and 47th minute, feeling connected to it, directing it, and sensing every audience member hanging on that last breath – it’s incredibly moving.

As he’s speaking, I look at his parents, who are completely rapt. They’re his audience tonight.

Read More

- Why Sona is the Most Misunderstood Champion in League of Legends

- SUI PREDICTION. SUI cryptocurrency

- Square Enix Boss Would “Love” A Final Fantasy 7 Movie, But Don’t Get Your Hopes Up Just Yet

- “I’m a little irritated by him.” George Clooney criticized Quentin Tarantino after allegedly being insulted by him

- House Of The Dead 2: Remake Gets Gruesome Trailer And Release Window

- US Blacklists Tencent Over Alleged Ties With Chinese Military

- Leaks Suggest Blade is Coming to Marvel Rivals Soon

- Why Fortnite’s Most Underrated Skin Deserves More Love

- „It’s almost like spoofing it.” NCIS is a parody of CSI? Michael Weatherly knows why the TV series is viewed this way in many countries

- Wuthering Waves: How to Build Carlotta (S0 / No Dupes)

2024-12-23 15:55