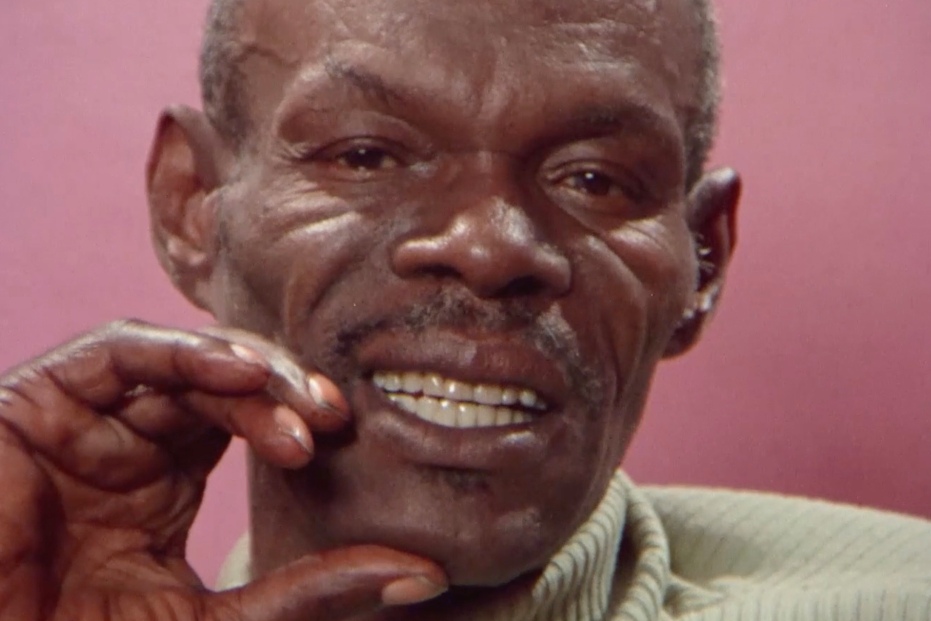

Michael Roemer recounts his initial encounter with reflecting glass at the age of 12. This mirror was situated above a sink in the bathroom of the dormitory where he resided as a student at Bunce Court boarding school in southeast England, having been relocated there as a young Jewish refugee fleeing Nazi Germany. “I’m certain we had mirrors back in Berlin, and in shop windows too,” he shares, “but I had never seen myself reflected before. And then, there I was, standing in the bathroom. I looked up, saw my reflection, and exclaimed, ‘That‘s me.’ In that instant, it felt like I hadn’t truly existed before that moment.” He laughs as he adds, “It wasn’t until I saw myself in the mirror that I realized I was real.”

Roemer has been active for quite some time, reaching the age of 97 recently, yet it’s a recurring pattern in his life and work that he often takes time to gain recognition. This week, two profoundly impactful films created by him over four decades ago will finally have their due recognition through independent distributor The Film Desk. The 1976 documentary titled “Dying” and the 1982 scripted feature “Pilgrim, Farewell” are set to debut at Film Forum, with plans for a nationwide expansion following. Although these films were once shown on PBS, they are now seldom screened and have been out of circulation on video for quite some time.

Roemer has experienced this situation multiple times before, including the restoration and release of his previously forgotten film “Vengeance Is Mine” in 2022. This movie, with its contemplative style and intimate dialogues, was like uncovering a hidden gem, hinting at a path American independent cinema hadn’t yet explored. The film’s revival occurred 33 years after another significant discovery – Roemer’s crime comedy “The Plot Against Harry,” shot in 1969 but shelved for decades due to failed screenings, finally made its festival rounds and hit theaters in 1989. Roemer decided to reintroduce this film after overhearing a video technician laughing while transferring it to video. His earlier work, “Nothing But a Man,” which depicts the challenges of a newlywed Black couple in Birmingham, Alabama, did get released initially but was limited by its subject matter. However, it became unavailable for a long time until a 1993 re-release and a restoration in 2012. Malcolm X was said to be a fan of this film.

For over four decades, Roemer, a film instructor at Yale, has been unusually humble about his work, unsure how audiences will respond to his latest creations, which are titled “Dying”. This documentary focuses on three individuals nearing the end of their lives and their families during those final months. The film is presented with minimal fanfare or sentimentality, yet it may prompt tears from viewers, not necessarily because it’s emotional but due to its raw and honest portrayal. Despite this, the camera remains steadfastly close, capturing intimate and candid moments. One patient’s wife admits that she wishes her husband would pass away swiftly so she can remarry while still young, fearing the challenge of raising two teenage boys as a single mother.

In the story of “Pilgrim, Farewell,” the main character, Kate (Elizabeth Huddle), while not directly resembling those in “Dying,” is similarly terminally ill. Like some of them, she grapples with a troubled uncertainty about how to confront her approaching death. Kate displays a range of emotions, from bitterness and cutting remarks, to carelessness, despair. Similar to other Roemer protagonists, her mood can swiftly change – a trait rarely seen in conventional films but strikingly reminiscent of real-life experiences. This work does not offer comforting cliches about the dignity of suffering or defying odds; instead, it gives the impression that Kate has already surpassed those stages before the narrative begins. Now, as she confronts her end, neither Kate nor the people around her – including her carpenter boyfriend, portrayed by a young, strong Christopher Lloyd, who was starting his role in the iconic TV series “Taxi” at this time – seem to know how to react.

As a movie enthusiast, I’ve always found conversations with Roemer to be an enthralling journey. His infectious love for peculiar narratives and his knack for painting vivid cinematic landscapes are truly unique. During our recent chat, he shared that he’s still immersed in his creative process, which only adds to the anticipation for his upcoming work.

What recollections do you have about Germany before your departure at the age of 11? I had a fairly vivid image of my surroundings and those around me during that time. However, my most vivid memory was the fear and helplessness I felt. My parents were quite melancholic individuals, so some of their sadness undoubtedly left an impact on me.

Could you share your recollections about the Kindertransport experience? I recall a train filled with approximately 30 children, and we gathered at a railway station. It seems I was the only child who managed to keep my tears at bay. I must have been quite stunned. My mother mentioned that many parents who watched us board the train took taxis to another Berlin station along our route, waving as the train passed without stopping. I do recall crossing the border into Holland. Perhaps the Dutch folks had seen similar trains before, for they were waiting at the platform with lemonade and cookies. I remember feeling a sense of relief upon leaving Germany, even though I didn’t fully grasp the situation at the time.

In Holland, we boarded a boat at a port near Rotterdam, then sailed across to Harwich on England’s east coast for an overnight voyage. We were provided with a food box and continued our journey by train, eventually arriving at a theater in London. All the children were seated on the stage, and as names were called out, someone from the audience would claim the corresponding child. My younger sister and I were among the last ones on stage. A woman who had been our pediatrician picked us up that night and took us to the school where we stayed for the next six years. The school was a grand manor house located in Kent, England’s southern region.

In an unusual tale, refugees often experience bizarre encounters; people’s lives intersect in the most unexpected manners. During my youth, our family spent a summer vacation at a hotel close to Hamburg. I had a standalone room, separate from another suite, although it shared a bathroom door with that suite. My governess and sister resided elsewhere within the building, but my room was part of this different suite. One day, while peering through the keyhole into that bathroom, I saw a reflection of another eye – it belonged to a girl I frequently played with during the day. She was in that other suite, spying on me as I was. Three years later, when I entered a grand English manor house in the dead of night, who did I encounter coming down the stairs? None other than this girl! However, we never spoke a single word to each other. This boarding school housed 120 children. We all became acquainted with one another over time. Yet, she and I always managed to avoid each other. It seemed as though we both held a secret about the other person.

It’s at that school in Kent where you initially developed a passion for art and drama, as you mentioned earlier. A remarkable man named Marckland, who often referred to me as his adopted son, was instrumental in this. As Marckland’s wife grew old, she reminisced and said, “Michael, you were his son.” I consider myself quite fortunate, given my lack of knowledge about my biological father and only minimal interaction with my mother. Marckland had previously been a theater director in both Germany and Spain, and he worked at our school maintaining the garden and stoking the boiler. I vividly recall regarding him as my father. It was under his guidance that I learned various skills. Admittedly, I was a poor actor. He directed some plays, one of which was George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, where he asked me to play the Dauphin. During rehearsals, everyone else seemed competent, but I struggled to find my footing. We practiced those scenes repeatedly, and I felt utterly confused.

In a memorable moment, I shared a glowing comment from a teacher about a school assignment with him when I was around 14 years old. I felt a surge of pride. Yet, he responded by suggesting I’d earn such praise for my performance in the play “Saint Joan.” Initially, I confessed ignorance on how to pull it off. But his response was simple and direct: “That’s how.” It seemed as if he had tapped into my self-doubt, helplessness, and pity, highlighting them like a beacon. From that moment forward, I found myself capable of portraying the role. To me, it felt as though he had unearthed some hidden ability within me. If someone is struggling to act out a scene, I can empathize with their predicament just by joining them on the floor. It’s challenging to express this feeling accurately. Often, I felt like an individual who lacked self-awareness and identity. Ironically, that vague sense of self allowed me to slip into any role more easily. I remained undefined, which enabled me to become anyone. Looking back, it feels as though that experience of nonexistence awakened something deep within me. It was a struggle between sinking or persevering, and my need to prove my existence drove me. I believe it’s why I took up painting and filmmaking.

Can you recall the moment when your passion for filmmaking first sparked? I remember watching a French film at Harvard, which was screened by a political group to raise funds. As I left the lecture hall, I declared, “This is what I want to do.” However, I had no idea how to pursue it. One day, an ad in the Crimson read, “Anyone interested in film?” There was no other film-related activity except these screenings. So, I went to Leavitt House and found about 50 undergraduates there. At our second meeting, we decided that everyone who wanted to make a film should write a script during the summer, and then a committee would choose one. When we met again in the fall, they asked for our scripts, and I was the only one with a script! No one could understand it, but since I wasn’t on the selection committee, they had no choice but to pick mine. The question then arose about who would direct the film. Since nobody had directed before, I spoke up and said, “Since it’s my script, I should direct.” Everyone agreed! So, that’s how it all started. It’s almost like Woody Allen’s joke about life: most of it is just showing up. My life has been a lot like that. We simply walked into the city and stopped traffic. No one stopped us from doing so because we looked like children, of course.

The movie titled “A Touch of the Times” could be the very first full-length film made at an American college. Now, let me share an intriguing tale about my journey to Harvard. My aunt, who was a doctor, immigrated to the U.S. in 1932 and saved our lives. After six years at school in Kent, she managed to secure passage for non-combatants like us to cross the Atlantic in early 1945. So, my sister and I made our way to the United States. When I arrived in Boston, my aunt asked me what I planned to do. I said I wanted to work in theater, but she advised me to attend college instead, suggesting a school on the other side of the river if I could get accepted. At that time, I had no idea about this school. My aunt arranged for me to meet someone she knew, an insurance company executive in Boston reminiscent of a Dickens character. He sat with his back to the corner at his desk. He suggested we meet in Harvard Yard. I’d never even been to Cambridge before. I took a couple of streetcars to get there and he led me into a building. A man behind a desk looked at my certificate, which showcased excellent grades from my Cambridge school graduation at age 16. Impressed, he said, “We’ll take that,” and I was enrolled. It wasn’t until much later that I learned the man behind the desk was the Dean of Admissions. This story has its share of quirks and twists, to say the least.

Wow, I can’t believe it! The person who introduced me was actually the secretary of the Boston Harvard Club! I had no clue where I was or what was going on. The United States was a complete mystery to me. It took years for me to figure things out. I didn’t have any money at all, so during college, I worked three jobs. My first day, I was in my dorm room which was right on the ground floor. My aunt told me it would take 20 years to live like this again, and she was spot on. Three meals a day, seven days a week, and you could even ask for seconds! It’s a luxury I hadn’t experienced since rationing in England, where we never saw an egg. At Harvard, I couldn’t afford the undergraduate uniform, so people gave me their old clothes instead.

After a long career, it’s quite unexpected yet delightful that some of the films I made are getting a second chance in the spotlight today. The film that brings me the most joy is “Vengeance is Mine,” as it resonates with younger audiences. Interestingly, when I showed it to my colleagues at Yale, they found it hard to grasp. They weren’t being unkind; they just didn’t understand it. On the other hand, “The Plot Against Harry” was a complete flop during production. I was convinced I had made a terrible mistake. The cast and crew, as well as my neighbors who watched it, disliked it initially. However, 20 years later, after its release at the New York Film Festival, they didn’t remember watching it. When I asked them if they understood it, they said yes, but when pressed, they couldn’t explain why.

It seems that “Pilgrim, Farewell” is the production that many find difficult to grasp due to its more distant and introspective nature. The film delves into aspects of humanity that some prefer to keep hidden, which can be uncomfortable for viewers. However, this is one of the benefits of theater or cinema; it provides a platform for those who feel isolated or troubled to realize they are not alone in their experiences. Unfortunately, this movie has received much criticism, and I’m not particularly excited about the upcoming screening.

How did the concept of creating films on the topic of dying arise?

I had produced numerous educational films, almost a hundred, some of which were broadcast at WGBH in Boston. They embarked on a project about death, and the National Endowment for the Humanities agreed to finance its production. However, their initial plan was to produce four half-hour films: one each on dying and painting, dying and poetry, dying and music, and another half-hour film showcasing funeral customs from various parts of the world. They approached me to create these films, but I declined, stating I couldn’t fulfill that task. Instead, I proposed a different approach: finding individuals who would allow us to document their end-of-life experiences as no one has returned from death that we are aware of.

Finding people willing to be filmed for this project proved to be quite challenging due to the emotionally taxing nature of the subject matter. As I encountered more and more individuals near death, it became increasingly difficult to continue. Each encounter seemed to add another layer of difficulty. It was impossible not to feel the weight of their impending demise, which made entering each room a struggle. When I shared these feelings with one of the nurses, she empathized, explaining that for them, entering a room meant they could offer some form of assistance, while I was powerless to do anything. This project turned out to be the most challenging I’ve ever undertaken.

Was there anything left unexplored or additional thoughts about the story of Dying that you wished to express, which prompted you to create Pilgrim, Farewell? No, actually. I had written Vengeance Is Mine, which I would complete a few years later, but the response I received from a woman at the Ford Foundation-funded project at PBS was very condescending. She said, “You don’t know how to write.” This remark made me so angry that I sat down and decided to create something with a minimal cast and limited setting, allowing me to finance it myself without relying on public funding. This is how Pilgrim, Farewell was born. It took me about a year and a half to write the script, which was intended for four characters. It’s a compact piece, like a chamber music performance. I wrote much of it here in Vermont, so that we could have such a small production that they couldn’t stop us from proceeding with the project.

The cast of Pilgrim, Farewell might have been modest in size, but it was exceptional nonetheless. And among them was Christopher Lloyd, who gained fame from his role in Taxi at around the same time. He even asked us if he could travel to L.A. to work with them on a show. We agreed, and soon after, he landed a part on Taxi. The making of this film was an unconventional joy. We were situated in a secluded town in Vermont called Post Mills, home to only four houses. Visitors often asked if they could join the crew or stay, but there was hardly any work available. There was just a unique charm about our small, dedicated team working intensely amidst the woods.

Currently, I’m engrossed in writing a book titled “One of You”. This book chronicles my journey from being a child on the brink of danger in Berlin, to finding myself in England and then the United States. Despite initially landing among my fellow immigrants in the Lower East Side, unforeseen circumstances led me to Harvard. My life has since followed an unexpected path, shaped by chance rather than design. The title “One of You” reflects how I now feel – having become an American and identifying with the many people here, no longer a part of an exclusive group.

Read More

- “I’m a little irritated by him.” George Clooney criticized Quentin Tarantino after allegedly being insulted by him

- South Korea Delays Corporate Crypto Account Decision Amid Regulatory Overhaul

- George Folsey Jr., Editor and Producer on John Landis Movies, Dies at 84

- Why Sona is the Most Misunderstood Champion in League of Legends

- ‘Wicked’ Gets Digital Release Date, With Three Hours of Bonus Content Including Singalong Version

- Destiny 2: When Subclass Boredom Strikes – A Colorful Cry for Help

- An American Guide to Robbie Williams

- Not only Fantastic Four is coming to Marvel Rivals. Devs nerf Jeff’s ultimate

- Leaks Suggest Blade is Coming to Marvel Rivals Soon

- Why Warwick in League of Legends is the Ultimate Laugh Factory

2025-01-28 21:55