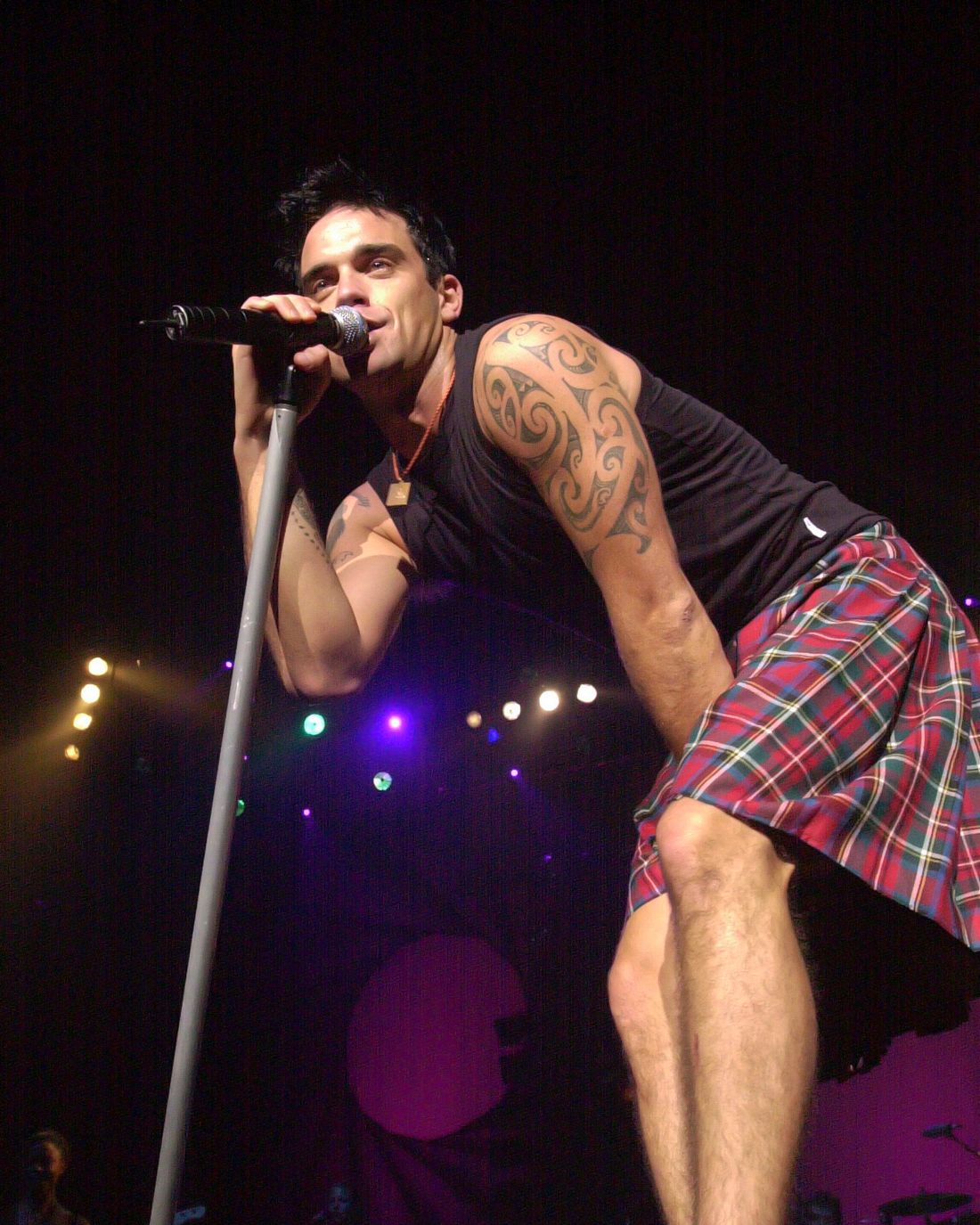

Last week, following the Los Angeles screening of the imaginatively conceived biopic “Better Man,” I observed several viewers swiftly pull out their phones and search for details about the film’s central character. For the previous two hours, they had witnessed the true-to-life tale of Robbie Williams – a globally successful British pop artist who has sold over 75 million records – being portrayed by a CGI monkey on screen. It seems my fellow cinema-goers required additional proof that the lead character in “Better Man” was indeed modeled after a real person.

Let’s consider as well that the Googlers might be Americans, given that Robbie Williams’s career is deeply embedded in British culture, much like the laws of football are to many Britons. Born as Robert Peter Williams in the ordinary city of Stoke-on-Trent, one of the top-selling solo artists in Britain historically, first tasted fame in the ’90s boy band Take That during his teenage years. However, Williams, who was eccentric and often off-key, clashed with the group’s strictness, leading him to depart in 1995. This separation had such an impact on fans that the charity Samaritans established a support line for them.

Departing would also establish the groundwork for the next fast-paced phase of Williams’s career. His debut album, Life Thru a Lens, produced numerous chart-topping songs, such as “Angels,” which became a staple at school dances and funerals alike. By the 2000s, Williams had become as integral to England as poor dental health and awkwardness. He was, as he proclaimed on his 2002 single “Handsome Man,” the one who embodied the “Brit” in “celebrity.

Despite his international success, Williams has consistently struggled to make a mark domestically. Whether “Better Man,” which was released recently, will be the breakthrough is uncertain. In the meantime, as a British expat in L.A., I am eager to educate this nation about the Robster and all that he embodies – the epitome of bighearted buffoonery’s patron saint.

His Survival Arc

As a cinephile, I find Robbie Williams’ journey to stardom an inspiring tale of meritocracy unfolding right before our eyes. Hailing from Stoke-on-Trent, a place that embodies working-class spirit and British charm, he defied the odds by breaking free from his roots and ascending into London’s high society.

What sets Robbie apart is his honesty, particularly when it comes to battling alcoholism and emerging victorious over two decades ago. His courage in addressing this struggle resonates with many of us. Moreover, his songs have become powerful anthems that magnify the small moments into something grand: “I hope I’m old before I die / Well, tonight I’m gonna live for today,” he croons on “Old Before I Die.”

Yet, what I admire most about Robbie is that there’s nothing extraordinary or exceptional about him. He acknowledges his lack of technical finesse but compensates with an infectious enthusiasm for entertaining. In many ways, he represents the everyman – a commoner elevated to superstar status. With a semi-theatrical singing voice, he’s a cruiseship performer who found colossal success by sheer force of will.

Robbie unapologetically invites us into his world and embraces his try-hardness, nowhere more evident than in the music video for “Rock DJ,” where he literally sheds his own skin to captivate the audience. It’s this audacious display that makes Robbie Williams a true original.

His Lovable Dickheadedness

Brash, bold, and full of playful mischief, Williams openly embraces the philosophy of just having a hearty good laugh, mate. His language, reminiscent of a British pub, is as natural as cigarette ash and diluted beer. He’s known for his frequent cheekiness. For example, he once exclaimed, “I’m rich beyond my wildest dreams!” at a press conference following his record-breaking £80 million signing with EMI in 2002. His primary purpose is to help us remember that nothing – even seriousness itself – should ever be taken too seriously. A few illustrative instances of this include:

- On inventing queerbaiting: “An awful lot of gay pop stars pretend to be straight. I’m going to start a movement of straight pop stars pretending to be gay.”

- On the then-51-year-old Madonna: “She looks amazing. I can’t believe she’s 89 and looks like that.”

- On his wife giving birth to his daughter: “It was like my favorite pub burning down.”

- On mediocre postmarital shagging: “The sex is nothing to write home about. It’s a shame because my mum loves those letters.”

- On his success: “I am the only man who can say he’s been in Take That and at least two members of the Spice Girls.”

His Confessional Approach

Williams’ songs frequently strike a balance between humor and introspection, encompassing elements of melancholy, self-criticism, and vulnerability. The humor in his work often stems from a deeply personal, painful place. His songs serve as a transparent window into his complex character – a man grappling with conflicting aspects, yearning for emotional sincerity. As he sings on “Feel,” “I just wanna feel real love / feel the home that I live in.” The song also contains one of the most poignant confessional lyrics: “I don’t wanna die / But I ain’t keen on living either.

Williams significantly shaped British music by introducing a deeply personal and insightful songwriting style that’s prevalent today. However, modern music often leans towards safe storylines and therapeutic pop jargon. In contrast, Williams’ lyrics were marked by a sense of daring and ambiguity. One moment his songs could express apathy and indifference, while the next they would amplify feelings to the brink of explosion. His music communicates an exceptionally nuanced level of emotional expression that elicits admiration – sometimes reluctantly – from almost every audience. Young people find themselves mirrored in his words. Teenagers empathize with him. Divorced fathers feel understood for the first time.

His Exposing the Realities of Fame

As a devoted cinema enthusiast, I’d like to rephrase this passage in my own words:

Long before the public awakened to the complexities of Britney Spears’ conservatorship and the perils of fame, Noel Gallagher of Oasis was already Britain’s skeptical anti-celebrity guru, ironically gaining even more attention. His songs frequently poked fun at the inner workings of the music industry, revealing how its power players sought to impose their commercial strategies on his artistic vision. In the catchy duet “Kids” with Kylie Minogue, they sang, “We’ll paint by numbers ’til something sticks.” While it may seem common today for musicians to lament the dehumanization of show business, Gallagher set an early precedent at a time when fame was at its most toxic and unchallenged. His commercial success coincided with a surge in celebrity worship and devaluation, leading to widespread skepticism and a lack of empathy for those experiencing fame. Yet, amidst the cynicism, Gallagher’s anti-celebrity voice resonated loudly. The more famous he became, the more he sang about the destructive aspects of fame, and people started to truly listen. “Yeah, I’m a star, but I’ll fade / If you ain’t sticking your knives in me / You will be eventually,” he warned on “Monsoon.” When one becomes famous, people tend to stop feeling sympathy for them. That’s the case for everyone, except Gallagher. As “Better Man” demonstrates, he’s the circus performer whose pain becomes our form of entertainment.

Read More

- INJ PREDICTION. INJ cryptocurrency

- SPELL PREDICTION. SPELL cryptocurrency

- How To Travel Between Maps In Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- LDO PREDICTION. LDO cryptocurrency

- The Hilarious Truth Behind FIFA’s ‘Fake’ Pack Luck: Zwe’s Epic Journey

- How to Craft Reforged Radzig Kobyla’s Sword in Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- How to find the Medicine Book and cure Thomas in Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

- Destiny 2: Countdown to Episode Heresy’s End & Community Reactions

- Deep Rock Galactic: Painful Missions That Will Test Your Skills

- When will Sonic the Hedgehog 3 be on Paramount Plus?

2025-01-08 23:54