Author: Denis Avetisyan

A large-scale study reveals that artificial intelligence can reliably identify harmful content related to U.S. elections with greater consistency than human reviewers.

Researchers demonstrate that Large Language Models achieve higher inter-rater reliability in multi-label classification of harmful social media posts, offering a scalable solution for content moderation.

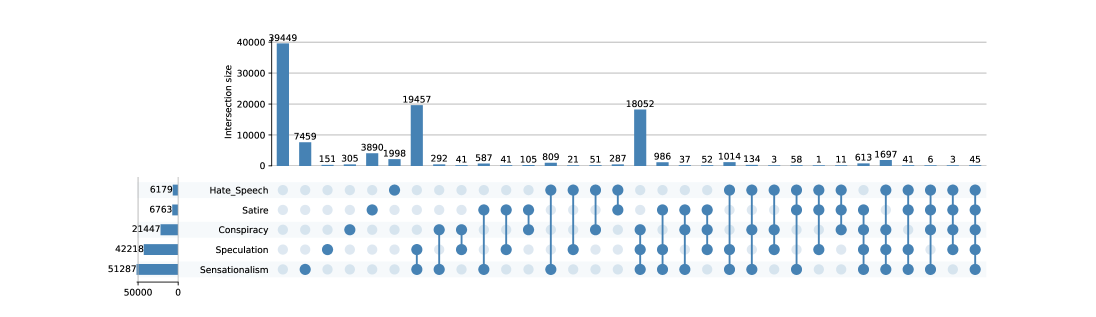

Detecting and categorizing harmful online content related to democratic processes remains a substantial challenge, particularly at scale. To address this, we introduce USE24-XD, a large-scale benchmark dataset investigated in ‘Wisdom of the LLM Crowd: A Large Scale Benchmark of Multi-Label U.S. Election-Related Harmful Social Media Content’, comprising nearly 100,000 posts from X (formerly Twitter) annotated for nuanced categories of harm. Our findings demonstrate that large language models (LLMs) not only achieve comparable inter-rater reliability to human annotators-and exhibit greater internal consistency-but also attain up to 0.90 recall on identifying speculative content. Given the observed influence of annotator demographics on labeling, how can we best leverage LLMs to build more objective and robust systems for monitoring and mitigating the spread of harmful election-related narratives?

The Erosion of Discourse: A Challenge to Rationality

The rapid spread of misinformation across social media platforms presents a substantial challenge to the foundations of informed public discourse. Unlike traditional media, where editorial processes and fact-checking served as gatekeepers, social media allows unverified claims to circulate widely and rapidly, often reaching vast audiences before they can be debunked. This creates an environment where false narratives can gain traction, shaping public opinion and eroding trust in legitimate sources of information. The sheer volume of content generated daily, coupled with the algorithmic amplification of engaging – but not necessarily accurate – posts, exacerbates the problem. Consequently, critical thinking skills are increasingly challenged, and the ability to distinguish between credible reporting and fabricated stories becomes significantly impaired, potentially undermining democratic processes and societal cohesion.

The sheer volume of user-generated content online presents a monumental challenge to those tasked with identifying harmful material. Human moderators face an escalating workload, struggling to keep pace with the constant influx of posts, comments, and videos. Beyond quantity, the nature of harmful content is becoming increasingly sophisticated – employing coded language, subtle dog whistles, and memetic strategies to evade detection. This necessitates not only a deep understanding of diverse cultural contexts and emerging online trends, but also the ability to discern malicious intent from protected speech, satire, or legitimate debate – a distinction that is often ambiguous and requires significant contextual awareness. The cognitive burden on moderators is immense, leading to potential for errors, burnout, and ultimately, a failure to effectively address the spread of dangerous information.

The automated identification of harmful online content faces considerable challenges when discerning malicious intent from protected forms of expression. Current methods often struggle with nuance, frequently misclassifying satire, parody, and legitimate, albeit strongly worded, opinion as harmful. This difficulty arises from the complex linguistic patterns inherent in these forms – irony, exaggeration, and rhetorical questioning – which algorithms trained on straightforward examples of hate speech or misinformation often fail to recognize. Consequently, content that utilizes these techniques can be incorrectly flagged, leading to the suppression of valuable discourse and raising concerns about censorship, while truly harmful content may evade detection due to its ability to mimic or disguise itself within seemingly acceptable formats.

The escalating volume of online content necessitates automated detection systems to identify harmful material, yet achieving accuracy proves remarkably challenging. Simple keyword filtering proves insufficient; nuanced language, including sarcasm, coded messages, and evolving slang, frequently bypasses these rudimentary approaches. Robust detection requires methods capable of parsing complex linguistic patterns – understanding not just what is said, but how it is said – and contextualizing language within broader conversations. Current research explores natural language processing techniques, including transformer models and contextual embeddings, to better capture semantic meaning and identify subtle indicators of harmful intent. Successfully navigating this complexity is paramount, as the effectiveness of content moderation – and the health of online discourse – increasingly relies on these sophisticated analytical tools.

Leveraging Linguistic Precision: An Automated Analytical Framework

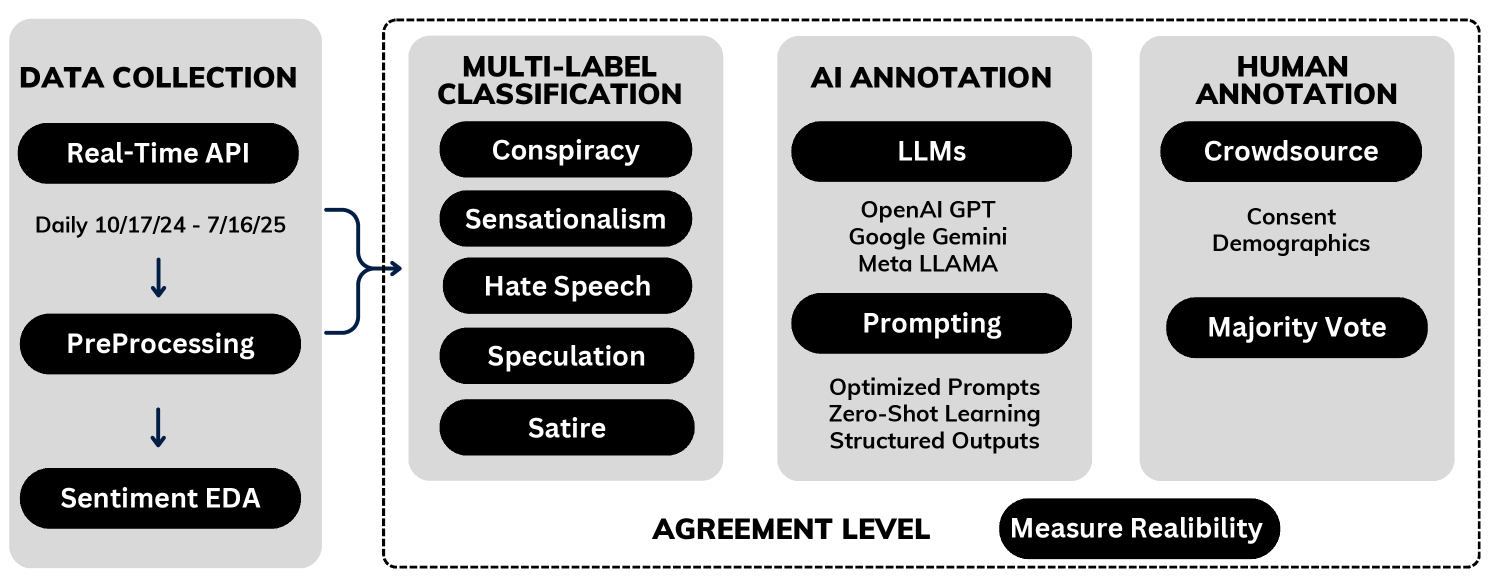

Large Language Models (LLMs) were implemented as the core technology for automatically categorizing content related to the U.S. election. This involved processing substantial volumes of text data – including social media posts, news articles, and online comments – and assigning relevant labels based on content characteristics. The selection of LLMs was driven by their capacity to understand and interpret natural language, enabling a scalable approach to content moderation and analysis that surpassed the limitations of traditional rule-based systems. The LLMs were integrated into an automated pipeline to facilitate rapid identification of content requiring further review, and to provide data for assessing trends in online discourse during the election period.

The content analysis pipeline incorporated a multi-label classification approach leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) to address the complexity of identifying multiple harmful content types within a single text post. Unlike traditional single-label classification, which assigns only one category to a given input, this method enabled the simultaneous detection of various harms – such as hate speech, threats, misinformation, and calls for violence – potentially coexisting within the same piece of content. This was achieved by training the LLM to predict the probability of each harmful content type independently, allowing for the assignment of multiple labels to a single post based on defined confidence thresholds. The implementation facilitated a more nuanced and accurate assessment of harmful content, capturing the multifaceted nature of online harms often present in user-generated text.

Traditional content analysis often relies on keyword detection, which identifies harmful content based on the presence of specific terms. However, this approach frequently produces false positives and negatives due to its inability to understand context, sarcasm, or nuanced language. Large Language Models (LLMs) address these limitations by analyzing the semantic meaning of text, enabling them to discern intent and identify harmful content even when it doesn’t explicitly contain prohibited keywords. This semantic understanding allows LLMs to differentiate between literal statements and figurative language, accurately classify content based on its meaning, and improve the precision of harmful content detection systems.

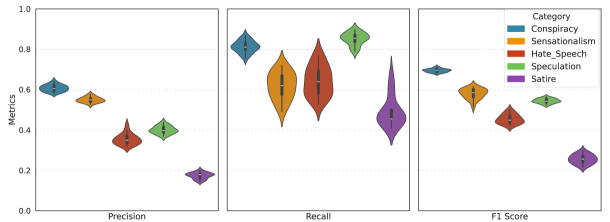

Preliminary evaluation of the Large Language Model (LLM) demonstrated the potential for identifying harmful content within the U.S. Election dataset; however, these initial results were subject to a comprehensive validation process. This validation included manual review of a statistically significant sample of LLM-annotated posts to assess precision and recall across different categories of harmful content. Discrepancies between LLM predictions and human annotations were analyzed to identify areas for model refinement and to establish confidence intervals for performance metrics. The validation process was critical to mitigating false positives and false negatives, ensuring the reliability of the LLM for downstream analysis and reporting.

Establishing a Ground Truth: Human Judgement as a Baseline

The USE24-XD Dataset comprises posts sourced from the X.com platform and was created through manual annotation performed by trained human experts. This dataset serves as a ground truth benchmark for evaluating automated content moderation systems. The selection of X.com posts was specifically designed to represent a diverse range of content potentially containing harmful material. Human annotation involved categorizing each post according to predefined guidelines, establishing a reliable reference point for comparison with the outputs of algorithmic models. The resulting annotations represent the expert judgement regarding the presence and type of harmful content within each post, forming the foundation for quantitative evaluation metrics.

Human annotators categorized X.com posts based on the presence of harmful content, utilizing predefined labeling guidelines to maintain consistency across the annotation process. These guidelines detailed specific criteria for identifying and classifying various forms of harm, including but not limited to hate speech, abusive language, and threats. Annotators were trained on these guidelines to minimize subjective interpretation and ensure a standardized approach to labeling. The categorization process involved assessing each post individually and assigning it to one or more relevant harmful content categories, thereby creating a granular and detailed dataset for subsequent analysis and model evaluation.

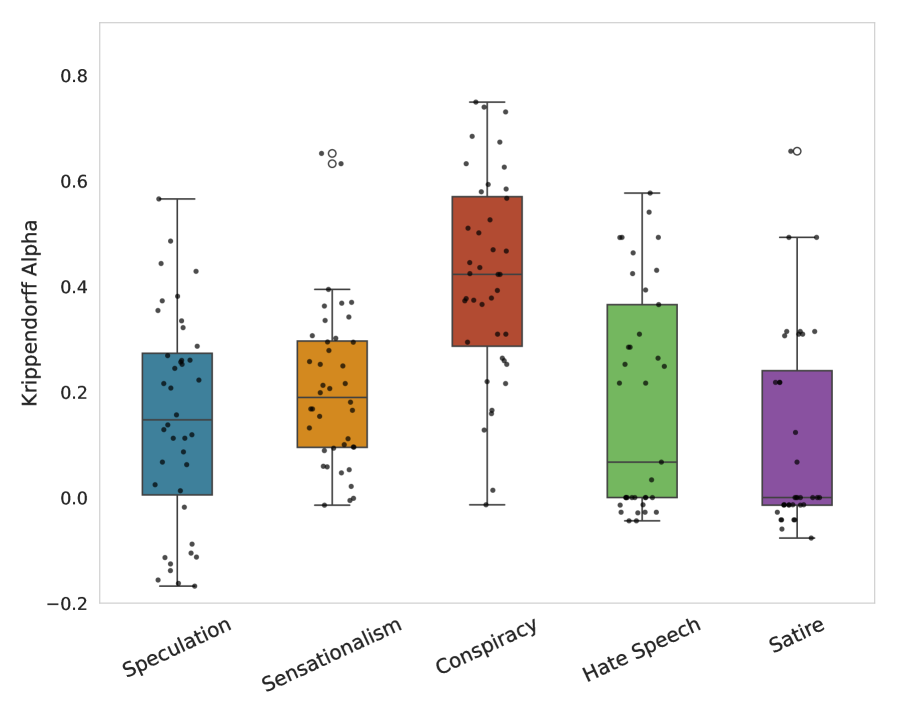

To establish the consistency of the human annotation process, inter-rater reliability was quantitatively measured using both Krippendorff’s Alpha and Cohen’s Kappa. Krippendorff’s Alpha, a statistic suitable for multiple annotators and various levels of measurement, yielded an average score of 0.62 across all categories. This indicates a moderate level of agreement among the annotators, suggesting a reasonable, though not perfect, consistency in their labeling of harmful content within the USE24-XD Dataset. While Cohen’s Kappa was also calculated, the Krippendorff’s Alpha score provides a more robust measure given the multiple annotators involved in the project.

To establish a definitive ground truth from multiple human annotations, a majority voting decision rule was implemented. This process aggregated responses from several annotators for each X.com post; the category assigned by the majority of annotators was then designated as the correct label for that post. This method effectively reduces the impact of individual annotator subjectivity or error, yielding a consolidated and more reliable dataset for evaluating automated harmful content detection systems. The resulting dataset represents a statistically-supported consensus, improving the robustness of benchmark comparisons and model training.

Validating Analytical Precision and Uncovering Underlying Themes

A detailed comparison between the large language model’s content classifications and human annotations highlighted both its capabilities and limitations in detecting harmful online material. The model demonstrated particular strength in identifying overtly abusive language and direct threats, achieving high accuracy in those categories; however, it struggled with nuanced forms of harm, such as subtle hate speech or manipulative disinformation, often requiring human review to confirm or correct its assessments. This suggests the LLM excels at pattern recognition of explicit indicators, but lacks the contextual understanding and critical reasoning necessary to consistently identify more sophisticated or ambiguous instances of harmful content. Consequently, the study underscores the potential of LLMs as powerful assistive tools for content moderation, but emphasizes the continued need for human oversight to ensure accuracy and prevent the misclassification of legitimate expression.

To discern the underlying currents within the USE24-XD Dataset, a Neural Topic Modeling approach was implemented, revealing prominent themes and narratives fueling the spread of harmful content. This technique moved beyond simple keyword identification, instead identifying complex relationships between terms to uncover latent topics discussed within the dataset. Analysis showed the prevalence of narratives centered around conspiracy theories, targeted harassment, and the promotion of extremist ideologies. By mapping these thematic clusters, researchers gained valuable insight into the diverse forms harmful content takes and how it’s framed, facilitating a more nuanced understanding of the dataset’s composition and potential for wider dissemination of harmful ideas.

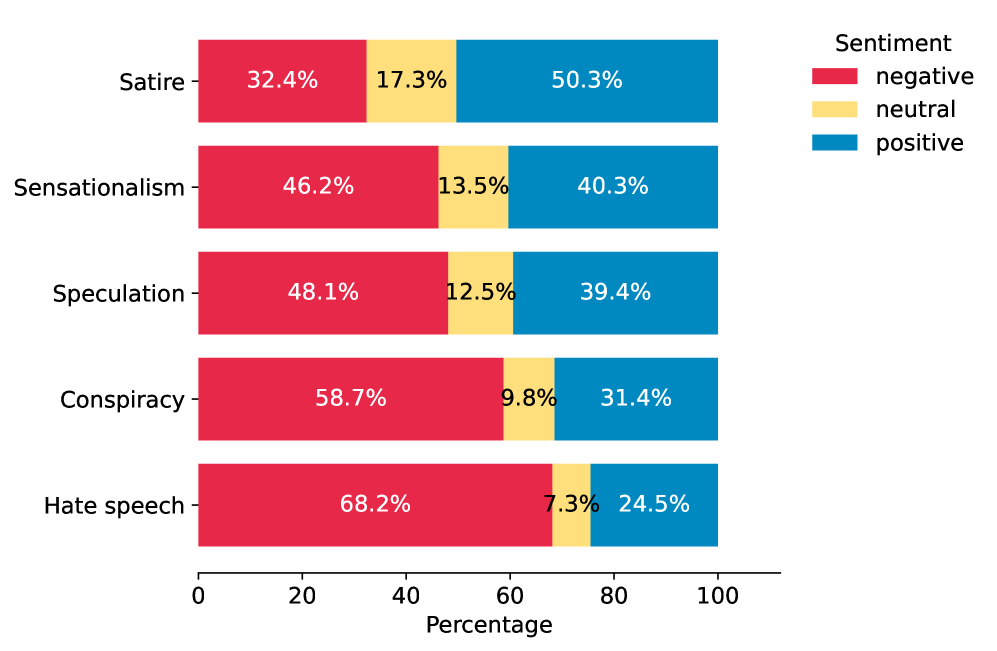

To further contextualize the nature of harmful content within the dataset, VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner) Sentiment Analysis was implemented. This approach systematically assessed each post’s emotional tone, quantifying the degree of positivity, negativity, or neutrality expressed within the text. The resulting sentiment scores offered valuable insights into how emotions contribute to the dissemination of harmful narratives; for example, identifying whether posts relying on outrage or fear were more likely to gain traction. By correlating sentiment with content categories, researchers could better understand the emotional drivers behind specific types of online harm, enriching the analysis beyond simple classification and providing a nuanced perspective on the spread of damaging information.

Recent research indicates that large language models (LLMs) demonstrate a surprising capacity for consistently categorizing online harmful content, even surpassing human-level agreement. The study reveals an LLM-achieved Krippendorff’s Alpha of 0.70, a measure of inter-annotator reliability, exceeding that of human annotators on the same task. Furthermore, when used to assist human annotation, these models significantly boost recall – the ability to identify all relevant instances of harmful content – achieving scores between 0.68 and 0.90 across various categories of online abuse. This suggests LLMs aren’t simply mimicking human judgment, but potentially applying a more consistent and comprehensive framework for identifying harmful online discourse, offering a valuable tool for content moderation and digital safety initiatives.

The pursuit of reliable annotation, as demonstrated within this research, echoes a fundamental principle of mathematical elegance. This study establishes that LLMs achieve consistently high inter-rater reliability – a form of invariant behavior as the dataset scales. Grace Hopper famously stated, “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” This sentiment applies here; rather than relying solely on the slow, often inconsistent process of human annotation, the researchers ‘asked forgiveness’ of traditional methods by leveraging LLMs. The resulting consistency isn’t merely about functional success, but about establishing a provable, repeatable process for identifying harmful content, akin to a theorem holding true regardless of the input – a cornerstone of true algorithmic purity.

What’s Next?

The demonstrated capacity of Large Language Models to achieve consensus in the classification of harmful content, exceeding that of human annotators, is not, strictly speaking, a surprise. Human judgment, after all, is notoriously susceptible to subjective interpretation – a flaw LLMs, when properly constrained, largely avoid. However, this merely shifts the locus of the problem. The fidelity of the LLM’s output remains entirely dependent on the precision of the initial prompt and the formal definition of ‘harmful’ itself. A vague or poorly defined label will yield, predictably, a vague and unreliable classification, no matter how consistently applied.

Future work must therefore prioritize not simply the scale of annotation, but the axiomatic clarity of the labels employed. The current study establishes a baseline for inter-rater reliability; the subsequent challenge lies in proving the correctness of the labels themselves. A purely empirical demonstration of agreement, however robust, is insufficient. Formal verification – a mathematically rigorous proof that a given post truly satisfies the definition of ‘harmful’ – is the ultimate, and currently largely unaddressed, goal.

Furthermore, the inherent limitations of any static definition must be acknowledged. Harmful content is not a fixed entity; it evolves, adapting to circumvent detection. A truly robust system will require continuous, automated refinement of its definitions, coupled with a formal mechanism for assessing the logical consistency of those definitions over time. Only then can one begin to speak of a truly intelligent system for content moderation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11962.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- My Favorite Coen Brothers Movie Is Probably Their Most Overlooked, And It’s The Only One That Has Won The Palme d’Or!

- Decoding Cause and Effect: AI Predicts Traffic with Human-Like Reasoning

- Hell Let Loose: Vietnam Gameplay Trailer Released

- Will there be a Wicked 3? Wicked for Good stars have conflicting opinions

- LINK PREDICTION. LINK cryptocurrency

- Landman Recap: The Dream That Keeps Coming True

- Exclusive: First Look At PAW Patrol: The Dino Movie Toys

- First Glance: “Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery”

- Thieves steal $100,000 worth of Pokemon & sports cards from California store

- 3 Best Movies To Watch On Prime Video This Weekend (Dec 13-14)

2026-02-14 22:04