Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research shows that advanced language models, when properly refined, can dramatically improve the detection of critical errors in translated text, paving the way for more reliable multilingual communication.

Instruction-tuned large language models, particularly with focused fine-tuning, offer a significant advancement in critical error detection for machine translation systems.

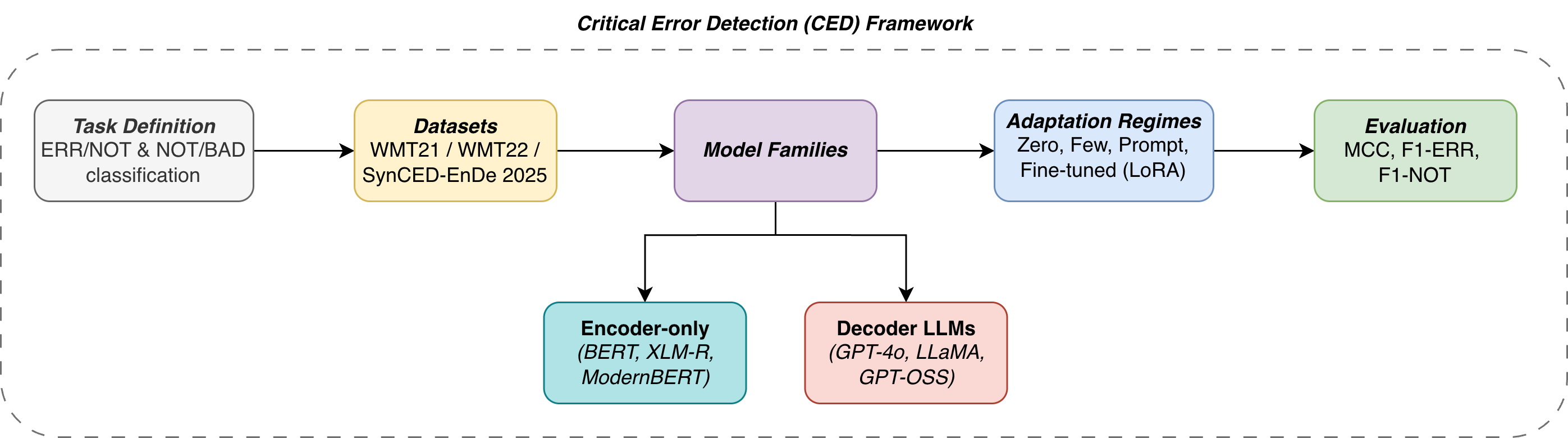

Despite the growing prevalence of machine translation, ensuring reliability and mitigating critical errors-such as factual inaccuracies or biased outputs-remains a significant challenge. This work, ‘Towards Reliable Machine Translation: Scaling LLMs for Critical Error Detection and Safety’, investigates the capacity of instruction-tuned Large Language Models to detect these errors, demonstrating that model scaling and fine-tuning consistently outperform traditional encoder-only baselines. Our findings suggest a pathway towards more trustworthy multilingual systems, reducing the risk of miscommunication and linguistic harm. Could improved error detection be a key safeguard in building truly responsible and equitable multilingual AI?

The Weight of Misinterpretation: Why Accuracy Isn’t Enough

Despite remarkable progress in machine translation, the technology isn’t immune to subtle errors that can have significant repercussions. These aren’t simply grammatical mishaps; they are nuanced misinterpretations capable of altering meaning in ways that impact crucial real-world scenarios. Consider medical diagnoses conveyed through translated patient records, legal documents requiring precise wording, or even international negotiations where a mistranslated phrase could escalate tensions. While modern systems excel at fluency, they can still stumble on ambiguity, cultural context, and idiomatic expressions, potentially leading to miscommunication, financial loss, or-in extreme cases-physical harm. The increasing reliance on machine translation across these sensitive domains underscores the urgent need for robust error detection and mitigation strategies that go beyond surface-level accuracy.

Despite remarkable progress in machine translation, current quality assurance relies heavily on automated metrics like BLEU, which primarily assess lexical overlap with reference translations. However, this approach frequently overlooks critical nuances in meaning and context, leading to deceptively high scores for translations containing subtle errors or culturally inappropriate phrasing. These metrics struggle to identify issues like incorrect gender assignments, mistranslated idioms, or the propagation of biases present in training data. Consequently, translations may appear fluent according to BLEU, yet fundamentally misrepresent the original intent or even cause offense. This disconnect between automated scores and actual translation quality underscores a significant gap in current evaluation methods and necessitates the development of more sophisticated techniques capable of capturing these nuanced errors and ensuring responsible machine translation.

The increasing reliance on machine translation demands a move beyond simple accuracy metrics towards a comprehensive assessment of potential harm. While translations may appear grammatically correct, subtle errors can drastically alter meaning, leading to miscommunication with serious consequences in fields like healthcare, legal proceedings, or international diplomacy. Consequently, research is now focused on identifying not just what errors occur, but also how those errors impact understanding and potentially exacerbate existing societal biases or create new inequities. This requires developing new evaluation frameworks that prioritize semantic fidelity, contextual relevance, and the mitigation of harmful outputs, shifting the emphasis from purely linguistic correctness to responsible and ethically-sound translation practices.

Beyond String Matching: The Nuances of Critical Error Detection

Critical Error Detection (CED) necessitates methods beyond simple string matching due to the complexities of natural language. Identifying deviations in meaning requires analyzing contextual information, including semantic relationships between words and phrases, as well as broader discourse features. This demands systems capable of understanding not just what is said, but how it is said, and whether the meaning aligns with the intended message. Techniques employed often include attention mechanisms, transformer networks, and contextual embeddings to capture these nuanced relationships and differentiate between acceptable paraphrases and critical errors that alter the overall meaning of a text.

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is a particularly suitable evaluation metric for critical error detection tasks involving imbalanced datasets, where the incidence of errors is low but their consequences are high. Unlike accuracy, which can be misleading when classes are unevenly distributed, the MCC provides a balanced measure of performance, considering true and false positives and negatives. Calculated as MCC = \frac{TP \cdot TN - FP \cdot FN}{\sqrt{(TP + FN)(TP + FP)(TN + FP)(TN + FN)}} , where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives respectively, the MCC yields a value between -1 and +1. A coefficient of +1 indicates perfect prediction, 0 indicates random performance, and -1 indicates total disagreement between prediction and observation, making it a robust indicator even when the positive class (errors) represents a small fraction of the total data.

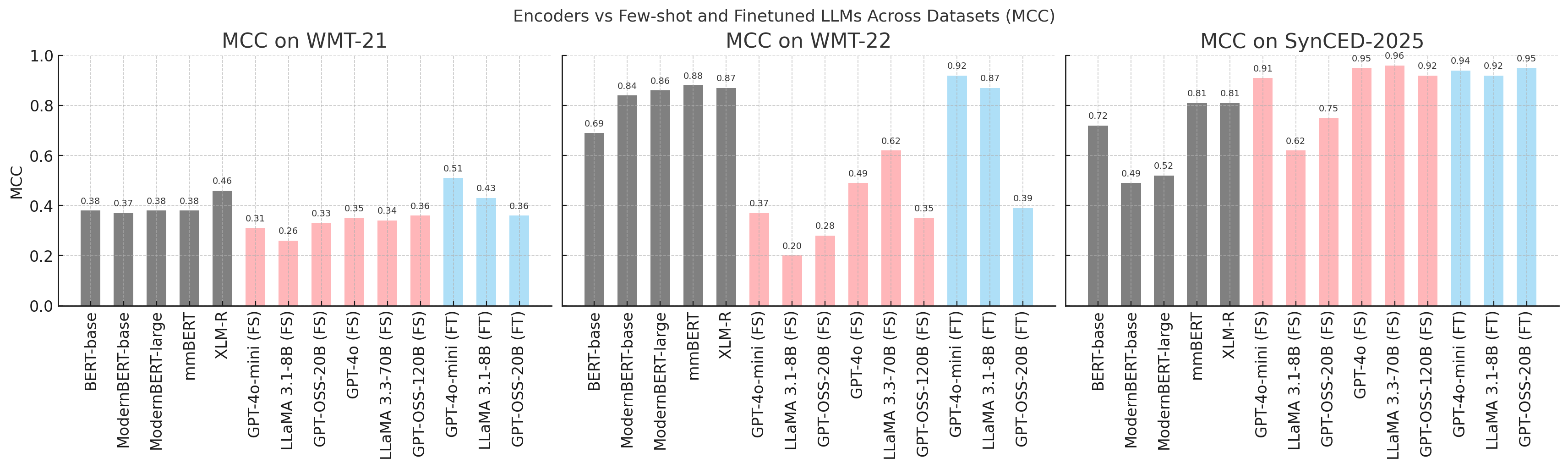

Standardized benchmarks and datasets are essential for the development and assessment of critical error detection systems. The Workshop on Machine Translation (WMT) 21/22 evaluation campaigns, alongside datasets like SynCED-En De 2025, provide consistent testing environments and data resources. Recent performance metrics demonstrate that encoder-only models, when evaluated on these benchmarks, can achieve a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of up to 0.88, indicating a strong ability to differentiate between correct and erroneous outputs, particularly in scenarios where errors are infrequent.

Leveraging Advanced Models: A Step Towards Reliable Translation

Encoder-only models, exemplified by XLM-R and ModernBERT, establish a robust base for machine translation through their capacity to efficiently encode input sequences into dense vector representations. These models utilize the Transformer architecture to process the entire input sequence simultaneously, capturing contextual relationships between words without inherent directional biases. This contrasts with autoregressive models that process text sequentially. The resulting encoded representation serves as a comprehensive summary of the input, facilitating downstream tasks like translation by providing a fixed-length vector that encapsulates the semantic meaning of the source text. Performance is optimized through techniques such as masked language modeling during pre-training, enabling the models to learn contextualized word representations and improve generalization to unseen data.

Instruction-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs), such as GPT-4o and LLaMA-3, present a promising approach to machine translation due to their inherent ability to follow natural language instructions. While these models exhibit strong zero-shot and few-shot translation capabilities, performance is substantially improved through adaptation techniques. Fine-tuning adjusts all model parameters, offering the highest potential accuracy but demanding significant computational resources. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) provides a parameter-efficient alternative by freezing the pre-trained model weights and introducing trainable low-rank matrices, reducing computational costs and storage requirements while maintaining competitive performance. The combination of instruction tuning with either fine-tuning or LoRA allows for efficient adaptation to specific translation tasks and domains, resulting in models that outperform traditional encoder-only architectures.

Zero-shot and few-shot learning capabilities improve the adaptability and robustness of large language models (LLMs) in machine translation tasks by enabling performance on unseen language pairs or domains with minimal task-specific training data. Specifically, a fine-tuned version of the GPT-4o-mini model has demonstrated a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.92 to 0.94 in critical error detection, a metric assessing the model’s ability to identify significant translation inaccuracies. This performance represents a substantial improvement over traditional encoder-only baseline models, indicating the enhanced capacity of instruction-tuned LLMs to accurately assess and potentially correct translation errors with limited data requirements.

The Power of Many: Ensemble Approaches for Robust Error Detection

Committee ensembles enhance the accuracy and stability of critical error detection systems through the aggregation of predictions from multiple individual models. This approach leverages the principle that combining diverse perspectives reduces the likelihood of systematic errors inherent in any single model. By utilizing a committee, the system benefits from a more comprehensive assessment, as disagreements among models highlight potential issues requiring further scrutiny. The resulting ensemble prediction is generally more reliable and less susceptible to noise or bias compared to the output of a standalone model, thereby improving the overall robustness of the error detection process.

The integration of diverse models within an ensemble approach is predicated on the principle that individual models will exhibit varying sensitivities to input data and possess distinct error profiles. By combining predictions from models trained with different architectures, datasets, or training parameters, the overall system reduces the likelihood of systematic errors. A model weak in detecting a specific error type may be compensated for by another model’s strength in that same area. This diversification minimizes the impact of individual model failures and increases the reliability of the collective prediction, thereby enhancing the robustness of the error detection system against unforeseen or challenging inputs.

Traditional machine translation evaluation relies heavily on n-gram overlap metrics like BLEU, which can fail to capture semantic accuracy or fluency. Metrics such as COMET and METEOR address these limitations by incorporating learned representations and considering recall in addition to precision. When employed alongside ensemble methods – combining predictions from multiple translation models – these metrics provide a more nuanced assessment of translation quality. Specifically, fine-tuned models utilizing these metrics have demonstrated an F1-score range of 0.94 to 0.96 in identifying critical errors within machine translation output, indicating a substantial improvement in error detection capabilities compared to simpler evaluation techniques.

Towards Responsible AI: Translation as a Force for Understanding

The development of robust error detection in machine translation is increasingly recognized as a core component of “IR-for-Good,” a movement dedicated to applying information retrieval technologies to address societal challenges. This approach moves beyond simply improving translation accuracy to proactively identifying and mitigating potentially harmful misinterpretations. By focusing on critical errors – those that could lead to misunderstandings with real-world consequences – researchers are building systems that prioritize responsible communication. This isn’t merely a technical refinement; it represents a shift towards leveraging AI to facilitate positive social impact, ensuring that machine translation serves as a bridge for understanding rather than a source of conflict or misinformation. The pursuit of critical error detection, therefore, embodies a commitment to ethical AI development and the harnessing of technology for the greater good.

Machine translation holds immense potential for bridging linguistic divides and fostering global interconnectedness, but realizing this promise necessitates a commitment to minimizing miscommunication. Beyond simply converting words from one language to another, accurate translation is crucial for preventing misunderstandings that could escalate conflicts or hinder vital collaborations. When machine translation systems prioritize nuanced meaning and contextual accuracy, they empower individuals and organizations to engage in more effective cross-cultural dialogue, enabling progress in fields ranging from diplomacy and humanitarian aid to scientific research and economic development. By reducing the potential for harmful interpretations, this technology can actively contribute to a more cooperative and understanding world, facilitating the exchange of ideas and building stronger relationships between diverse communities.

The development of truly trustworthy artificial intelligence, particularly in the realm of machine translation, demands sustained investigation and innovation. Current systems, while increasingly sophisticated, still exhibit vulnerabilities to bias and error, potentially leading to miscommunication with significant real-world consequences. Future research must prioritize not only enhanced accuracy but also the development of robust methods for detecting and mitigating harmful outputs, alongside a deeper understanding of the socio-cultural contexts informing translation. This ongoing effort is essential to ensure that machine translation serves as a tool for global collaboration and understanding, rather than a source of division or misinformation, ultimately aligning technological advancement with the broader needs of humanity.

The pursuit of reliable machine translation, as detailed in this work, demands a relentless focus on identifying and mitigating critical errors. It echoes Vinton Cerf’s sentiment: “The Internet treats everyone the same.” This equality, while powerful, necessitates robust error detection-for a mistranslation, however minor, can disproportionately impact understanding and trust. The paper’s success with instruction-tuned Large Language Models isn’t merely a technical achievement; it’s a step towards ensuring this digital equality doesn’t come at the cost of accuracy. The demonstrated improvement in error detection isn’t about adding complexity, but about refining the signal from the noise, aligning with the principle that clarity, not embellishment, is the mark of true progress.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated improvements in critical error detection are, naturally, encouraging. Yet, the pursuit of ‘reliability’ often feels like building ever-taller towers on foundations of sand. This work, while effectively leveraging instruction tuning, skirts the deeper question of what constitutes a ‘critical’ error in translation. Is it fidelity to source meaning, avoidance of harm, or something else entirely? The answer, predictably, is ‘it depends’-a phrase that rarely advances scientific understanding. They called it ‘scaling LLMs’ as if sheer size could solve problems of nuance.

Future work will undoubtedly explore more elaborate architectures and training regimes. But a more fruitful path might lie in acknowledging the inherent limitations of automated translation. Perhaps the goal isn’t to eliminate errors, but to develop systems that reliably indicate their own uncertainty. A humble translator, aware of its fallibility, is surely more trustworthy than a confident one.

The field should also resist the temptation to treat ‘multilingual reliability’ as a monolithic concept. Errors that are critical in a medical context are different from those in a casual conversation. A more granular approach-one that explicitly models the stakes of translation-is essential. Simplicity, it seems, is not merely a design preference, but a moral imperative.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11444.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- My Favorite Coen Brothers Movie Is Probably Their Most Overlooked, And It’s The Only One That Has Won The Palme d’Or!

- Adolescence’s Co-Creator Is Making A Lord Of The Flies Show. Everything We Know About The Book-To-Screen Adaptation

- The Batman 2 Villain Update Backs Up DC Movie Rumor

- Hell Let Loose: Vietnam Gameplay Trailer Released

- Thieves steal $100,000 worth of Pokemon & sports cards from California store

- Decoding Cause and Effect: AI Predicts Traffic with Human-Like Reasoning

- Will there be a Wicked 3? Wicked for Good stars have conflicting opinions

- Games of December 2025. We end the year with two Japanese gems and an old-school platformer

- The 1 Scene That Haunts Game of Thrones 6 Years Later Isn’t What You Think

- Bitcoin’s Wild Ride: Binance’s Stash Vanishes Like a Fart in the Wind 🌪️💨

2026-02-13 15:30