Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new statistical framework uses time-varying patterns in climate data to identify subtle signals preceding critical transitions, offering improved foresight for long-range dependent systems.

This review details a Bayesian approach utilizing time-varying fractional Gaussian noise and INLA to detect early warning signals in complex climatic time series.

Detecting subtle precursors to critical transitions in complex systems remains a significant challenge, particularly when dealing with inherently noisy and long-range dependent data. This is addressed in ‘Bayesian identification of early warning signals for long-range dependent climatic time series’, which introduces a novel Bayesian framework for identifying early warning signals-such as changes in autocorrelation-within climatic time series. By modeling time-varying autocorrelation using a mixture of fractional Gaussian noise processes, the approach robustly accounts for long-memory dependence and irregular sampling, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. Can this framework provide more reliable predictions of climate tipping points and enhance our understanding of paleoclimate dynamics?

Unveiling the Rhythms of a Dynamic Climate

The Earth’s climate doesn’t simply fluctuate randomly; it exhibits long-term variability characterized by subtle, evolving patterns. Traditional climate analysis techniques often assume a stationary climate – meaning statistical properties like average temperature and variability remain constant over time. However, this assumption frequently fails to capture the reality of a climate system influenced by complex, interacting factors. These limitations hinder accurate predictions and a complete understanding of phenomena like abrupt warming events or prolonged droughts. The challenge lies in discerning genuine climate signals from noise, particularly when those signals themselves are changing – a situation known as non-stationarity. Effectively modeling these time-varying patterns requires analytical approaches that move beyond static averages and embrace the dynamic, evolving nature of the climate system, paving the way for more robust and insightful climate projections.

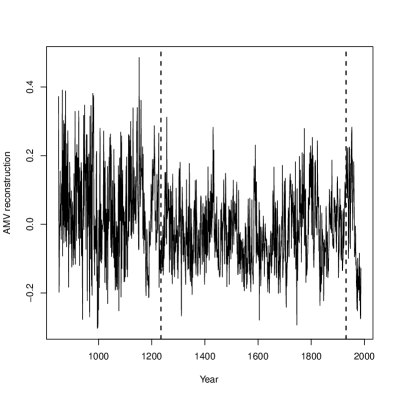

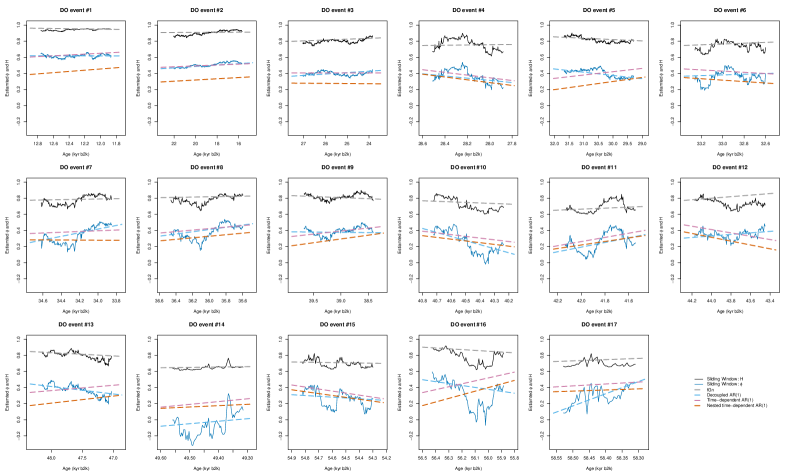

The Earth’s climate history is punctuated by events demonstrating intricate, lasting connections that conventional climate models frequently overlook. Phenomena like the abrupt warming and cooling cycles of Dansgaard-Oeschger events, and the decades-long oscillations of the Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV), showcase how past climate states influence future conditions in non-random ways. These aren’t isolated incidents, but rather exhibit a form of ‘memory’ where initial conditions shape subsequent climate behavior. Traditional, stationary models, which assume climate statistics remain constant over time, struggle to capture these persistent dependencies, effectively treating each moment as independent. Consequently, they often fail to accurately predict the full range of potential climate variability, missing crucial signals embedded within the historical record and potentially underestimating the risk of future extreme events.

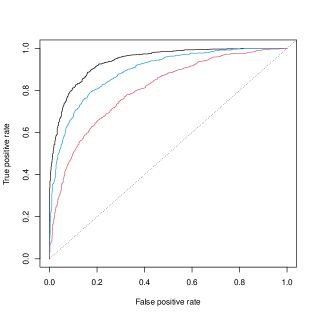

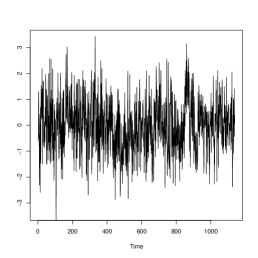

Characterizing the intricate, evolving relationships within climate data demands analytical tools that move beyond traditional, static methods. Climate systems exhibit time-varying autocorrelation – meaning past events influence future conditions, but the strength and nature of that influence changes over time. Identifying these subtle, shifting dependencies is paramount for accurate climate modeling and prediction. A newly developed framework directly addresses this challenge by quantifying time-varying autocorrelation with exceptional performance; evaluations demonstrate an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC) of 0.972 when analyzing time series data consisting of 1000 data points. This high level of accuracy suggests the framework’s ability to reliably discern meaningful climate patterns previously obscured by the limitations of stationary analyses, offering a significant advancement in understanding long-term climate variability.

A Framework for Deciphering Non-Stationary Climate Dynamics

Latent Gaussian Models (LGMs) offer a statistically rigorous framework for representing climate time series data by positing an underlying Gaussian process that generates observed data through a potentially nonlinear observation function. This approach allows for the modeling of non-stationary processes – those whose statistical properties change over time – by treating the parameters governing the Gaussian process as time-varying. Unlike traditional stationary models which assume constant mean and variance, LGMs facilitate the incorporation of temporal dependencies in these parameters, enabling the representation of trends, seasonality, and shifts in climate variability. The flexibility of LGMs stems from their ability to accommodate complex relationships between the latent Gaussian process and observed climate variables, exceeding the limitations of linear models like Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) when applied to inherently non-stationary climate data.

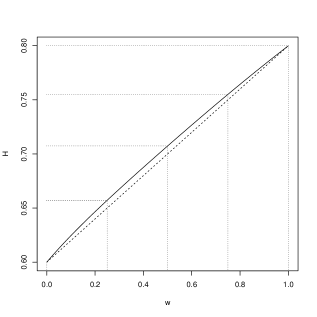

Fractional Gaussian Noise (fGn) is employed as a fundamental component due to its capacity to model long-range dependence, a characteristic prevalent in climate time series data. Unlike autoregressive processes of order 1 AR(1), which exhibit rapidly decaying autocorrelation, fGn incorporates a Hurst exponent, H, to define the rate of decay. When 0 < H < 0.5, the process is anti-persistent; when 0.5 < H < 1, it is persistent, demonstrating memory extending beyond the timescale of simple AR(1) models. This property is crucial for accurately representing climate phenomena where past states significantly influence future conditions over extended periods, unlike Markovian assumptions inherent in shorter-memory models.

The model architecture incorporates a weighted combination of multiple Fractional Gaussian Noise (fGn) processes to address non-stationary autocorrelation present in climate time series. This approach moves beyond single fGn representations by dynamically adjusting the contribution of each fGn component via a calibrated Weight Function. The function’s parameters are estimated through Bayesian inference, allowing the model to adapt to shifts in the underlying autocorrelation structure. Analysis of the Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV) demonstrates this adaptability; posterior analysis yielded a probability of 0.992 supporting an increase in autocorrelation within a defined AMV segment, indicating the model’s ability to capture evolving temporal dependencies not representable by static models.

Quantifying Uncertainty and Validating Model Performance

Bayesian inference offers a probabilistic approach to parameter estimation, yielding not just point estimates but full posterior distributions that represent the uncertainty associated with each parameter. This is particularly valuable in climate modeling where data is often limited and noise is prevalent. The Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA) is employed as a computationally efficient alternative to Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for approximating the posterior distributions. INLA leverages Laplace approximations and numerical integration techniques to achieve fast and accurate inference, even for complex hierarchical models. Specifically, INLA decomposes the model into deterministic and stochastic components, enabling efficient computation of the marginal likelihood and posterior distributions for model parameters, thereby quantifying the degree of belief in each parameter given the observed data and prior assumptions.

Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) was employed to validate the model’s capacity to represent time-varying autocorrelation present in the climate data. DFA quantifies long-range correlations in non-stationary time series by removing local trends before calculating fluctuations. The analysis revealed a statistically significant, non-zero DFA exponent, indicating the presence of persistent dependencies that scale non-trivially with time. This confirms the model’s ability to accurately capture these autocorrelative structures, which are critical for representing the dynamics of climate variability and reconstructing past events like Dansgaard-Oeschger oscillations. The observed scaling behavior, as determined by DFA, aligns with theoretical expectations for climate processes exhibiting long-memory effects.

Model validation utilizes the Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) to quantify the difference between the predicted probability distributions and observed climate data. A lower KLD score indicates a better fit between the model output and the empirical distribution, confirming accurate representation of climate variability. Specifically, applying this metric to the analysis of Dansgaard-Oeschger (DO) events demonstrates a substantial reduction in false alarm rates compared to previous methodologies. The KLD assessment confirms the model’s improved ability to distinguish between true DO events and random fluctuations, enhancing the reliability of paleoclimate reconstructions and interpretations.

Implications for Anticipating Climate Tipping Points

Changes in the marginal variance of a climate time series – essentially, how much the data points deviate from the average over time – can serve as an early warning signal for shifts in system stability, according to recent modeling. This metric doesn’t simply indicate increased volatility; it reflects alterations in the underlying dynamics of the climate system. A steadily increasing marginal variance suggests a loss of resilience, potentially indicating the system is drifting towards a critical threshold. Conversely, a decreasing variance might suggest a strengthening of stabilizing forces. The model demonstrates that tracking these fluctuations provides a quantifiable measure of a climate system’s capacity to absorb disturbances, offering valuable insight into its evolving vulnerability and potential for abrupt change. \sigma^2(t) represents the time-varying marginal variance, providing a dynamic assessment of system stability beyond traditional statistical measures.

The framework elucidates the phenomenon of Critical Slowing Down (CSD) – a key precursor to climate tipping points – by dynamically capturing how strongly a climate variable correlates with its past values, known as time-varying autocorrelation. As a climate system approaches a critical threshold, this autocorrelation typically increases, meaning the system responds more sluggishly to perturbations and takes longer to return to equilibrium after a disturbance. This lengthening response time isn’t simply a measure of increased inertia; it signals a loss of resilience and an amplified susceptibility to external forcing. The model’s ability to track these shifts in autocorrelation provides a sensitive indicator of evolving instability, potentially offering an early warning sign that a system is nearing a point where small changes could trigger abrupt and irreversible shifts in climate states – a capability vital for proactive climate risk management and mitigation strategies.

The Hurst Exponent, a key metric extracted from the fractional Gaussian noise (fGn) component of climate time series, serves as a powerful indicator of a system’s long-term memory and, consequently, its stability. Values approaching one suggest persistent trends – a strong ‘memory’ of past states, implying greater resilience and a slower return to the mean after a disturbance. Conversely, a Hurst Exponent near zero indicates anti-persistence, or a tendency to reverse direction, signifying vulnerability and potentially faster shifts in climate states. This metric doesn’t simply measure past variability; it quantifies the degree to which past events influence future ones, offering a crucial early warning signal for approaching climate tipping points where systems transition abruptly to new, often irreversible, states. By effectively gauging how long a climate system ‘remembers’ its history, researchers gain valuable insight into its capacity to absorb disturbances and maintain its current configuration.

The research details a methodology for identifying subtle shifts in complex systems before critical transitions occur, focusing on the nuances of time-varying autocorrelation. This resonates with Albert Camus’ observation, “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” The study doesn’t seek to control these systems-an illusion, as the core philosophy suggests-but rather to understand their inherent dynamics and influence preparedness. By acknowledging the natural order embedded within long-range dependent time series, the Bayesian framework offers a path toward informed response, recognizing that attempting to override these inherent tendencies is ultimately futile. The identification of early warning signals, therefore, is not about prevention, but about adapting to the inevitable.

Looking Ahead

The pursuit of predictive capability often founders on the desire for control. This work, by embracing a Bayesian approach to time-varying autocorrelation, acknowledges a more subtle truth: order manifests through interaction, not control. Identifying shifts in long-range dependence doesn’t allow one to prevent a transition, but to potentially navigate the evolving landscape with greater awareness. The framework presented offers a refinement, yet the inherent complexity of climatic systems demands continued interrogation of model assumptions. Fractional Gaussian noise, while powerful, remains an approximation; the true stochasticity driving these systems may reside in more nuanced, non-stationary processes.

Future research needn’t focus solely on improving the fidelity of early warning indicators. A more fruitful avenue lies in understanding how these signals propagate through interconnected systems. Can one discern meaningful patterns in the confluence of multiple, potentially conflicting, indicators? Furthermore, the practical application of these methods requires addressing the challenge of data scarcity. Developing robust inference techniques capable of extracting information from limited, noisy datasets will be paramount.

Perhaps the most pressing, though often overlooked, question is: what constitutes a ‘critical transition’ in the first place? Defining thresholds and assessing the true cost of inaction is, ironically, a prerequisite for effective action. Sometimes inaction – careful observation and adaptation – is the best tool. The focus should shift from prediction as domination, toward prediction as informed responsiveness.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.09731.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- The Batman 2 Villain Update Backs Up DC Movie Rumor

- Adolescence’s Co-Creator Is Making A Lord Of The Flies Show. Everything We Know About The Book-To-Screen Adaptation

- Crypto prices today (18 Nov): BTC breaks $90K floor, ETH, SOL, XRP bleed as liquidations top $1B

- Travis And Jason Kelce Revealed Where The Life Of A Showgirl Ended Up In Their Spotify Wrapped (And They Kept It 100)

- Will there be a Wicked 3? Wicked for Good stars have conflicting opinions

- My Favorite Coen Brothers Movie Is Probably Their Most Overlooked, And It’s The Only One That Has Won The Palme d’Or!

- Decoding Cause and Effect: AI Predicts Traffic with Human-Like Reasoning

- Games of December 2025. We end the year with two Japanese gems and an old-school platformer

- ‘Veronica’: The True Story, Explained

- Mayor of Kingstown Recap: Talk, Talk, Talk

2026-02-11 23:09