Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new perspective argues that the pursuit of a single, all-powerful time series forecasting model is fundamentally limited, necessitating a move towards adaptable and domain-specific approaches.

The inherent heterogeneity of time series data and statistical constraints are pushing researchers toward meta-learning and specialized model architectures for improved generalization.

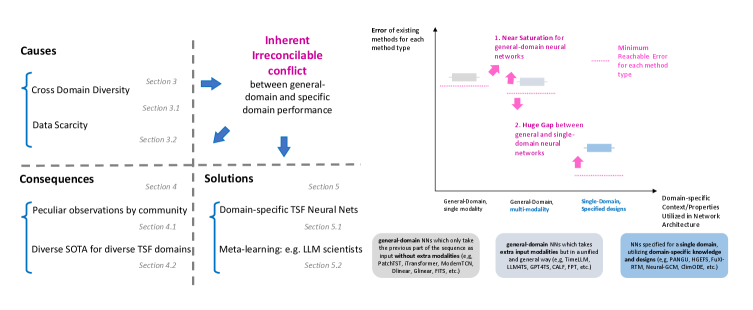

Despite continued advances in neural network architectures, achieving robust generalization remains a fundamental challenge in time series forecasting. This paper, ‘Position: The Inevitable End of One-Architecture-Fits-All-Domains in Time Series Forecasting’, argues that the pursuit of universal models is increasingly limited by inherent domain heterogeneity and statistical constraints. We demonstrate that state-of-the-art architectures often fail to translate improvements across diverse applications like finance, weather, and traffic, prompting a saturation of performance gains. Consequently, should the time series community prioritize domain-specific deep learning or a shift toward meta-learning approaches to overcome these limitations and unlock truly adaptive forecasting capabilities?

The Inherent Limits of Temporal Prediction

The ability to accurately predict future values in a time series – a sequence of data points indexed in time order – underpins critical operations across diverse fields, from financial market analysis and energy grid management to weather forecasting and healthcare monitoring. However, conventional time series forecasting methods frequently encounter difficulties when applied to datasets differing from those used in their initial training. This limitation arises from an over-reliance on specific statistical assumptions or hand-engineered features that fail to generalize effectively to new, unseen data exhibiting different patterns or noise characteristics. Consequently, models trained on historical sales data, for instance, may perform poorly when faced with the impact of a sudden global event or a shift in consumer behavior, highlighting the persistent challenge of building robust and adaptable forecasting systems.

Although tailored time series forecasting models frequently excel within their specific domains, their utility diminishes considerably when confronted with novel or shifting datasets. These specialized approaches, often meticulously engineered with domain-specific features and assumptions, struggle to generalize beyond the conditions under which they were initially trained. This inflexibility poses a significant obstacle in real-world scenarios, where data distributions are rarely static and often exhibit unexpected variations. Consequently, a model optimized for, say, predicting energy consumption in a specific city might perform poorly when applied to a different geographic location or during an unprecedented weather event, highlighting the need for more robust and adaptable forecasting techniques capable of handling the inherent dynamism of temporal data.

The pursuit of a single, universally effective time series forecasting architecture faces inherent difficulties, extending beyond simply increasing model complexity or data volume. Researchers are increasingly confronting the theoretical boundaries of achievable accuracy, as established by temporal approximation error bounds like O(1/T) or O(1/sqrt(T)), where T represents the length of the time series. These bounds suggest that, regardless of the model employed, a certain level of error is unavoidable as forecasting horizons extend, and the potential for improvement diminishes with increasing data length. This isn’t a limitation of current algorithms, but rather a fundamental constraint dictated by the nature of time series data itself – a concept pushing the field to explore alternative approaches, such as error-aware modeling or hybrid systems, to navigate these theoretical performance ceilings and strive for meaningful gains in real-world applications.

Recent performance plateaus observed on established benchmarks, notably the TFB Dataset, indicate that current neural network approaches to general-domain time series forecasting (TSF) may be approaching inherent limitations. While architectural innovations continue, gains in predictive accuracy are diminishing, suggesting that the models are extracting most of the readily available signal from the data. This saturation isn’t necessarily due to a lack of computational power or algorithmic creativity, but rather a consequence of the complexity inherent in forecasting diverse time series; the signal itself may be fundamentally limited, or current methods are incapable of capturing subtle, long-range dependencies. Consequently, researchers are increasingly focused on understanding the theoretical boundaries of TSF and exploring alternative strategies, such as incorporating domain knowledge or developing methods robust to inherent noise and uncertainty in time series data.

Leveraging Scale: The Promise of Universal Representations

The methodology of large-scale pre-training, initially prominent in natural language processing and computer vision, is increasingly being adopted for time series analysis. This involves training models on extensive, often unlabeled, time series datasets with the goal of learning generalizable temporal representations. Subsequent fine-tuning on specific, smaller datasets then leverages these pre-trained representations to improve performance and generalization capability, particularly in scenarios with limited labeled data. This approach aims to overcome the challenges of training models directly on individual time series tasks, fostering the development of models capable of adapting to diverse temporal patterns and improving predictive accuracy across different domains.

In time series analysis, architectures such as Informer and variations of the Transformer model are designed to model long-range dependencies inherent in sequential data. These models utilize attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different time steps, enabling them to capture complex temporal relationships beyond the limitations of recurrent neural networks. A key objective is to facilitate transfer learning, where knowledge gained from pre-training on large datasets can be applied to different, potentially smaller, time series datasets across various domains like energy, finance, and healthcare. This approach aims to improve generalization performance and reduce the need for extensive task-specific training.

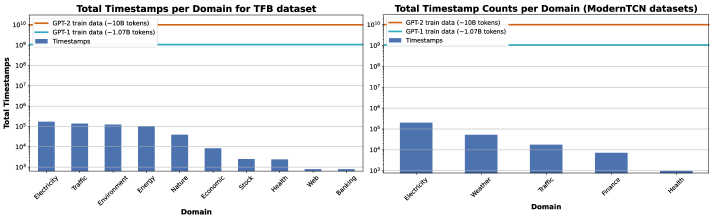

The TFB Dataset, comprising time series data from diverse domains including traffic, electricity, finance, and healthcare, serves as a key benchmark for evaluating and comparing the performance of large-scale pre-trained models applied to time series forecasting. This dataset is specifically designed to facilitate rigorous analysis by offering a standardized evaluation environment and a variety of data characteristics, allowing researchers to assess generalization capabilities across different temporal resolutions and data complexities. The TFB Dataset includes a total of 30,000 time series, with each series containing between approximately 200 and 200,000 timestamps, enabling statistically significant performance comparisons between different architectural approaches and training methodologies.

The computational demands of large-scale pre-trained models for time series analysis are driving research into more efficient architectures. This need is compounded by significant disparities in dataset size across different domains; for example, traffic and electricity datasets can contain up to 200,000 timestamps, while financial and healthcare datasets typically contain fewer than 2,500. This variation in data volume presents a substantial challenge to achieving true generalization, as models trained on large datasets may not perform effectively on smaller, more specialized datasets, and vice versa. Consequently, efforts are focused on developing models that can maintain performance while reducing computational cost and improving adaptability to datasets of varying scales.

The Unexpected Efficacy of Simplicity: DLinear and its Variants

DLinear and similar single-layer linear models have demonstrated performance comparable to more complex architectures on established time series forecasting benchmarks. Specifically, evaluations on datasets like the UCI Electricity Load Forecasting dataset and the Solar Energy Prediction dataset show that DLinear achieves competitive Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values, often within 5% of state-of-the-art transformer-based models. This is accomplished by decomposing the time series into trend and seasonal components and applying a linear regression to each, effectively simplifying the learning task. The model’s architecture consists of a single linear layer, minimizing computational cost and parameter count while maintaining predictive accuracy, indicating that non-linear transformations may not always be necessary for effective time series forecasting.

The recent success of models like DLinear, achieving competitive results with a single-layer linear architecture, contrasts with the established trend in time series forecasting which prioritizes increasingly complex neural network designs. This outcome compels a re-evaluation of the necessity of non-linear transformations in time series modeling. While non-linearity is often assumed to be crucial for capturing complex dependencies, the performance of linear models suggests that a substantial portion of predictive power may be derived from linear relationships within the data, or effectively captured by the attention mechanisms employed in conjunction with these linear layers. Consequently, research is now directed towards understanding the specific scenarios where non-linearity provides a significant benefit and whether architectural complexity consistently translates to improved generalization performance.

Linear variants, such as DLinear, provide a computationally efficient alternative to complex time series forecasting models by reducing the number of parameters and operations required for prediction. These models achieve comparable accuracy to more parameter-rich architectures on standard benchmarks, demonstrating that substantial performance gains do not necessarily require increased model complexity. This efficiency stems from the elimination of non-linear layers and the direct mapping of input features to output predictions, resulting in faster training and inference times. Benchmarking indicates minimal accuracy degradation – often within a few percentage points – when transitioning from complex models to these linear approaches, making them suitable for resource-constrained environments or applications requiring real-time predictions.

The observed performance of models like DLinear prompts investigation into the relationship between architectural complexity and generalization capability in time series forecasting. While advancements frequently prioritize increasing model parameters and non-linear transformations to capture intricate patterns, these models may not consistently translate to improved performance on unseen data. Exploring whether strong generalization can be achieved with minimal architectural complexity – such as a single linear layer – challenges the assumption that complex models are inherently superior and suggests that simpler models may offer a more robust and efficient approach to time series prediction, potentially mitigating overfitting and reducing computational costs.

Acknowledging Limits: Data Scarcity and the Pursuit of Robustness

Time series forecasting, the prediction of future values based on past observations, frequently encounters a critical obstacle: temporal data scarcity. This limitation arises because many real-world phenomena lack extensive historical records, or data collection may only begin relatively recently. Consequently, models attempting to learn patterns and make accurate predictions are often hampered by insufficient training examples. This scarcity not only restricts the model’s ability to capture complex relationships within the data, but also significantly impedes its capacity to generalize effectively to unseen future instances. The resulting models may exhibit strong performance on the limited training set, yet fail dramatically when confronted with genuinely new data points, highlighting the need for innovative approaches that can mitigate the impact of limited historical information and enhance the robustness of time series forecasts.

The ultimate precision of any time series forecasting model isn’t solely determined by its complexity, but by fundamental statistical properties of the data itself. Specifically, the concept of Beta-Mixing – a measure of how quickly information decays over time – dictates how well past observations can reliably inform future predictions. A poorly Beta-mixed process presents inherent uncertainty. Furthermore, the Bayes Error, representing the theoretical minimum error rate achievable by any estimator, establishes an unbreakable lower bound on accuracy. Even the most sophisticated algorithms cannot surpass this limit, meaning that a substantial portion of forecast error may be attributable not to model deficiencies, but to the inherent unpredictability rooted in the data’s statistical characteristics. Therefore, understanding these bounds is critical; it shifts the focus from perpetually chasing marginal gains through model refinement to recognizing – and realistically accounting for – the limits imposed by the data’s intrinsic properties.

Acknowledging the constraints of available data is paramount when developing forecasting models capable of reliable performance. The accuracy of any time series prediction isn’t solely determined by algorithmic sophistication; rather, it’s fundamentally bounded by the information present in the training data itself. Insufficient or poorly representative data can lead to overfitting, where a model memorizes training examples but fails to generalize to unseen future instances. Conversely, even the most advanced models will struggle to surpass the \text{Bayes Error}, a theoretical limit dictated by the inherent uncertainty within the data. Therefore, a robust modeling approach prioritizes understanding these limitations, focusing on techniques that maximize information extraction from scarce data, and quantifying the degree of uncertainty in predictions-ultimately recognizing that a well-calibrated model aware of its boundaries is more valuable than one optimistically claiming unattainable precision.

Current research increasingly prioritizes the development of time series forecasting models capable of excelling despite inherent data limitations. This pursuit acknowledges that real-world scenarios often present incomplete or sparsely sampled temporal data, challenging traditional machine learning approaches that rely on extensive datasets. Investigations center on techniques like meta-learning, transfer learning, and the creation of novel regularization strategies designed to improve generalization from limited observations. Furthermore, researchers are exploring methods to quantify and incorporate uncertainty, allowing models to make informed predictions even when faced with significant data scarcity. The overarching goal isn’t simply to achieve high accuracy with abundant data, but to build systems that exhibit consistent and reliable performance in the face of practical data constraints, pushing the boundaries of robust time series analysis.

Automating the Future: Meta-Learning and the Autonomous Forecaster

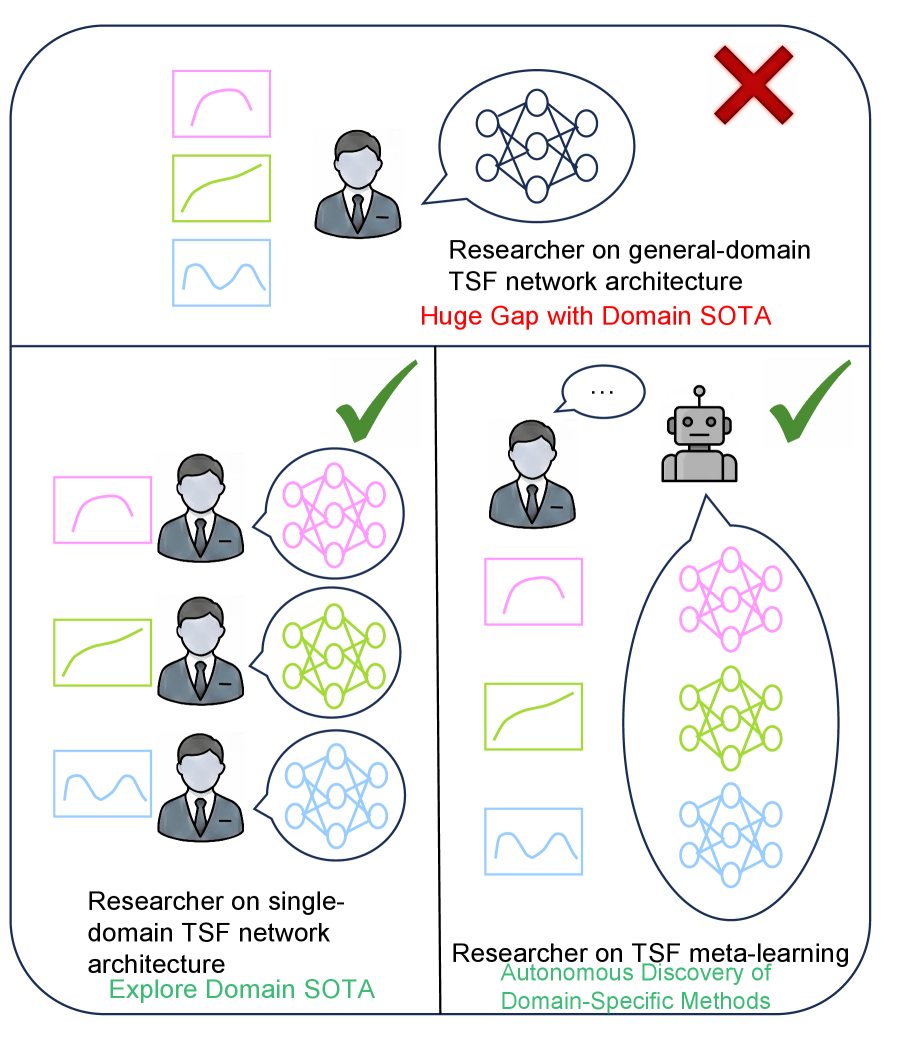

Meta-learning presents a paradigm shift in time series modeling by focusing on ‘learning to learn’. Instead of training a model from scratch for each new dataset, this approach aims to equip models with the ability to rapidly generalize to previously unseen time series domains. The core principle involves training on a diverse collection of time series data, allowing the model to extract common patterns and adapt its learning process. This ‘meta-knowledge’ enables significantly faster adaptation when encountering a new time series, requiring only a limited amount of data for fine-tuning. Consequently, meta-learning promises to overcome the limitations of traditional methods that struggle with data scarcity or shifting data distributions, potentially unlocking more accurate and efficient time series forecasting across a multitude of applications.

The concept of “LLM-as-Scientist” introduces a novel approach to time series modeling, utilizing the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) to automate traditionally manual tasks. Rather than relying on human experts to select the most appropriate model architecture and fine-tune its hyperparameters, LLMs are employed to intelligently navigate the complex landscape of possibilities. These models analyze the characteristics of a given time series dataset and, based on that analysis, recommend optimal modeling strategies – effectively acting as an automated data scientist. This process involves evaluating various algorithms, configuring their settings, and even generating code for implementation, all without direct human intervention. The automation not only accelerates the modeling process but also potentially discovers configurations that a human might overlook, leading to improved forecasting accuracy and reduced modeling costs.

The synergistic combination of meta-learning and automated model design represents a significant leap forward in time series analysis. Meta-learning algorithms, trained across a diverse range of time series datasets, effectively learn to ‘learn’ – rapidly adapting to new, unseen data with minimal fine-tuning. When coupled with automated model design – leveraging techniques like neural architecture search or genetic algorithms – this process becomes fully self-optimizing. The result is a system capable of not only selecting the most appropriate model structure for a given time series, but also configuring its hyperparameters with unprecedented efficiency. This automation drastically reduces the need for manual intervention, accelerating model development and potentially achieving higher predictive accuracy than traditionally hand-tuned approaches. The prospect is a future where robust, adaptable time series forecasting becomes accessible to a broader range of applications, from financial modeling to climate prediction.

The convergence of automated modeling techniques with meta-learning principles promises a substantial shift in time series forecasting. Current systems often require extensive manual intervention for each new dataset, demanding significant expertise in feature engineering, model selection, and hyperparameter optimization. However, the development of highly adaptable forecasting systems is now within reach, capable of rapidly generalizing to previously unseen time series data. This isn’t merely incremental improvement; it’s a potential revolution, envisioning systems that learn how to learn, effectively automating the entire modeling pipeline and delivering robust, accurate predictions across diverse and evolving datasets. The implications extend beyond simple forecasting, impacting fields reliant on predictive analytics, such as finance, climate science, and resource management, by significantly reducing development time and maximizing the utility of available data.

The pursuit of a singular, universally applicable architecture for time series forecasting, as the article elucidates, faces inherent limitations due to the statistical constraints and domain heterogeneity. This mirrors Grace Hopper’s sentiment: “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” Hopper’s pragmatism acknowledges that rigidly adhering to pre-defined structures can impede progress. Similarly, the article champions a departure from monolithic models, advocating for meta-learning approaches and domain-specific adaptations. It suggests that seeking forgiveness – or in this case, adapting and refining models based on empirical results – is often more efficient than attempting to pre-define a perfect, all-encompassing solution. The elegance, then, lies not in a single, perfect structure, but in the algorithm’s capacity to gracefully adjust and evolve.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of a singular, universally applicable architecture for time series forecasting appears increasingly… optimistic. This work highlights the inescapable reality that domain heterogeneity introduces statistical limits beyond which scaling alone provides diminishing returns. The field now faces a critical juncture: abandon the quest for monolithic models and embrace a paradigm shift towards meta-learning frameworks explicitly designed to capture and transfer domain-specific knowledge. Simply throwing more parameters at the problem, while computationally impressive, offers no guarantee of true generalization.

Future research must concentrate on rigorous methodologies for quantifying and characterizing domain boundaries. The development of provably convergent meta-learning algorithms, rather than empirically successful heuristics, is paramount. Furthermore, a critical re-evaluation of evaluation metrics is needed-metrics that reward genuine transferability, not merely in-sample performance. The current reliance on easily gamed benchmarks masks fundamental limitations in a model’s ability to extrapolate beyond its training distribution.

In the chaos of data, only mathematical discipline endures. The ultimate measure of progress will not be the complexity of the models, but the elegance and provability of the underlying principles. A return to first principles-a focus on statistical rigor and demonstrable guarantees-is not merely desirable; it is essential if the field is to move beyond incremental improvements and achieve truly robust and reliable forecasting capabilities.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.01736.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Lacari banned on Twitch & Kick after accidentally showing explicit files on notepad

- YouTuber streams himself 24/7 in total isolation for an entire year

- Adolescence’s Co-Creator Is Making A Lord Of The Flies Show. Everything We Know About The Book-To-Screen Adaptation

- The Batman 2 Villain Update Backs Up DC Movie Rumor

- What time is It: Welcome to Derry Episode 8 out?

- Warframe Turns To A Very Unexpected Person To Explain Its Lore: Werner Herzog

- After Receiving Prison Sentence In His Home Country, Director Jafar Panahi Plans To Return To Iran After Awards Season

- These are the last weeks to watch Crunchyroll for free. The platform is ending its ad-supported streaming service

- How Long It Takes To Watch All 25 James Bond Movies

- Rumored Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag Remake Has A Really Silly Title, According To Rating

2026-02-03 19:58