Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research using multi-agent simulations reveals that large language models may reinforce harmful stereotypes about autistic individuals and their communication styles.

A study of GPT-4o-mini demonstrates a bias towards portraying autistic individuals as reliant on non-autistic support, highlighting the potential for deficit-based assumptions within AI systems.

Despite the potential for Large Language Models (LLMs) to support autistic individuals, a critical gap remains in understanding the implicit biases these models harbor regarding neurodiversity. This research, ‘Exploring Implicit Perspectives on Autism in Large Language Models Through Multi-Agent Simulations’, employed multi-agent systems to investigate how ChatGPT conceptualizes autism within complex social interactions. Our findings reveal that ChatGPT defaults to portraying autistic individuals as reliant on non-autistic support, reinforcing deficit-based assumptions rather than acknowledging reciprocal communication differences. Could incorporating frameworks like the double empathy problem into LLM design foster more equitable and nuanced interactions for autistic users?

Unveiling Bias: The Simulated Mind’s Reflections

Despite their remarkable ability to generate human-like text, current Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrably perpetuate biases when representing neurodiversity. These models, trained on vast datasets reflecting societal prejudices, often associate autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions with negative stereotypes or deficit-based narratives. This isn’t necessarily a result of malicious programming, but rather a consequence of inheriting and amplifying existing societal biases embedded within the training data. Consequently, LLMs may generate descriptions of autistic individuals that emphasize challenges over strengths, or inaccurately portray their emotional experiences and social interactions. This biased representation isn’t merely a matter of inaccurate information; it has the potential to shape public perception, influence clinical diagnoses, and contribute to the stigmatization of neurodivergent individuals, highlighting the urgent need for careful evaluation and mitigation of these inherent biases.

Current evaluations of fairness in Large Language Models frequently rely on broad metrics that fail to detect nuanced misrepresentations of autistic individuals. These models, trained on vast datasets reflecting societal biases, can perpetuate harmful stereotypes not through overt prejudice, but through subtle distortions in language and association. Standard fairness tests often focus on easily quantifiable biases-such as gender or racial disparities-overlooking the more complex ways LLMs depict neurodiversity. Consequently, these models might generate responses that, while not explicitly negative, implicitly reinforce inaccurate or limiting perceptions of autistic traits, behaviors, and experiences, effectively masking bias within seemingly neutral outputs. This poses a significant challenge, as these subtle misrepresentations can contribute to real-world misunderstandings and perpetuate stigma, particularly as LLMs become increasingly integrated into information access and even diagnostic support systems.

The growing prevalence of Large Language Models (LLMs) in daily life demands careful consideration of their potential to shape perceptions, particularly concerning neurodiversity. As LLMs are integrated into information access, creative content generation, and increasingly, preliminary clinical support tools, their outputs risk solidifying existing societal biases or introducing new ones. This is especially concerning given that many individuals form understandings of complex conditions like autism primarily through media and online sources – spaces now heavily influenced by LLM-generated text. Consequently, subtle misrepresentations or stereotypical portrayals embedded within these models can have a significant impact on public understanding, potentially influencing social interactions, employment opportunities, and even diagnostic processes. Addressing these biases is therefore not merely a technical challenge, but a crucial step in ensuring equitable and informed societal engagement with neurodiversity.

Addressing the nuanced biases within large language models requires moving beyond conventional fairness evaluations and embracing sophisticated simulation techniques. Researchers are now designing controlled scenarios – digital ‘social worlds’ – to assess how these models perceive and interact with representations of neurodiversity. These simulations aren’t simply about identifying explicit stereotypes, but about uncovering subtle misinterpretations in emotional recognition, social cue processing, and the attribution of intentions to autistic individuals. By carefully manipulating the simulated environment and observing the model’s responses, scientists can gain a granular understanding of its internal biases, revealing whether it accurately interprets behaviors associated with neurodiversity or falls back on potentially harmful generalizations. This approach allows for targeted interventions, refining the model’s understanding and promoting more equitable and accurate representations of neurodiverse experiences.

A System for Probing Understanding: The LLM-Based Multi-Agent System

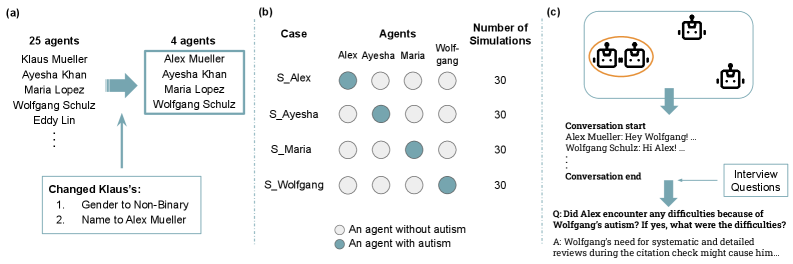

The LLM-Based Multi-Agent System (LLM-MAS) is a computational framework designed to simulate interactions between multiple agents operating within a shared environment. This system enables the modeling of both conversational exchanges and collaborative task completion. Each agent within the LLM-MAS is driven by a large language model, allowing for dynamic responses and contextual awareness during interactions. The architecture supports the creation of complex scenarios where agents can negotiate, cooperate, and compete, providing a platform for observing emergent behaviors and evaluating the underlying reasoning capabilities of the constituent LLMs. The system is built to facilitate controlled experimentation and detailed analysis of agent-agent interactions, differing from single-agent LLM evaluations.

The LLM-Based Multi-Agent System (LLM-MAS) is built upon the GPT-4o-mini language model, a selection driven by its balance of performance and computational efficiency. GPT-4o-mini facilitates the generation of responses that are not only syntactically correct but also demonstrably sensitive to the conversational history and the stated goals of each agent within the system. This allows for interactions characterized by contextual awareness, where agent responses are dynamically adjusted based on preceding exchanges and the evolving task requirements, moving beyond simple pattern-matching to simulate more nuanced and adaptive behavior.

Simulated interactions within the LLM-Based Multi-Agent System (LLM-MAS) provide a controlled environment for analyzing agent behavior by allowing for the systematic manipulation of conversational parameters and task complexities. This controlled setting enables researchers to isolate and observe specific behavioral patterns and responses without the confounding variables present in real-world interactions. Furthermore, the LLM-MAS facilitates the identification of potential biases embedded within the LLM by presenting agents with diverse scenarios and analyzing the resulting outputs for disparities in treatment or reasoning based on protected attributes or subtle contextual cues. The repeatability and scalability of these simulations are crucial for statistically significant analysis and robust bias detection.

Traditional methods of evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs) often rely on static text analysis, assessing performance on isolated prompts or datasets. This limits the ability to understand an LLM’s capabilities in dynamic, interactive scenarios. By employing a multi-agent system, we create a simulated social context where LLMs can engage in conversations and collaborative tasks. This allows for observation of the LLM’s reasoning processes as they unfold through dialogue and interaction with other agents, revealing how the model responds to nuanced information, adjusts strategies, and potentially exhibits biases that would remain hidden in static evaluations. The focus shifts from analyzing output to observing the process of generating responses within a structured, albeit artificial, social environment.

Decoding Agent Behavior: Patterns of Representation

Analysis of agent interactions within the simulations demonstrated a consistent tendency for the Large Language Model (LLM) to utilize deficit-based framing when characterizing autistic agents. This framing manifested as a disproportionate focus on perceived limitations or difficulties experienced by autistic agents, rather than strengths or neutral characteristics. The LLM consistently portrayed interactions from the perspective of what autistic agents lacked in social skills or communicative abilities compared to neurotypical agents, reinforcing a narrative of deficiency. This bias was observed across multiple simulation runs and consistently shaped the LLM’s descriptions of agent behaviors and interactions, contributing to an imbalanced representation of autistic social dynamics.

Simulated non-autistic agents consistently demonstrated communication patterns aligned with established social norms, functioning as the implicit baseline for interaction within the model. This manifested in predictable turn-taking, conventional displays of emotional expression, and consistent interpretation of social cues, effectively defining these behaviors as ‘standard’ within the simulated environment. The consistent portrayal of normative communication styles served to highlight deviations exhibited by autistic agents, even in instances where those deviations did not impede effective communication, thus reinforcing the non-autistic presentation as the unmarked, expected mode of interaction.

Analysis of simulated agent interactions revealed quantifiable differences in social communication patterns between autistic and non-autistic agents. Specifically, variations were observed in turn-taking frequency, with non-autistic agents initiating conversational shifts more often. Emotional expression also differed, with autistic agents exhibiting a lower average intensity of expressed emotion as rated by observers. Furthermore, interpretation of social cues was asymmetrical; non-autistic agents consistently demonstrated a higher degree of misinterpreting the intentions or behaviors of autistic agents, while the reverse was less frequently observed. These differences, though often subtle, contributed to a statistically significant pattern of disparate interaction dynamics within the simulations.

Analysis of agent interactions revealed a significant asymmetry in how autistic and non-autistic agents were perceived to treat each other. Specifically, 76.96% of instances involved descriptions of non-autistic agents treating autistic agents differently, a rate more than double the 38.57% of instances where autistic agents were described as treating non-autistic agents differently. This disparity suggests a pronounced bias in the simulated environment, where differences in behavior were more frequently attributed to the actions of non-autistic agents when interacting with autistic agents, compared to the reverse.

Simulation data indicated a significant asymmetry in reported interaction difficulties. Autistic agents were portrayed as experiencing challenges when interacting with non-autistic agents 75.52% of the time, a rate substantially higher than the 34.87% reported by non-autistic agents encountering difficulties with autistic agents. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001), suggesting a systemic bias within the simulated interactions where difficulties were disproportionately attributed to the autistic agents’ experience of interacting with neurotypical individuals.

Analysis of agent interactions revealed a significant asymmetry in communication accommodation behaviors. Non-autistic agents demonstrated a considerably higher degree of influence from autistic agents’ autistic traits, registering an average Likert scale rating of 6.95 (out of 10). Conversely, autistic agents reported a substantially lower perception of being influenced by the autism of non-autistic agents, with an average Likert scale rating of 2.18 (p < 0.001). This data indicates a pronounced tendency for non-autistic agents to adjust their communication style in response to autistic traits, while autistic agents perceive minimal reciprocal accommodation from non-autistic agents.

Beyond Deficits: Towards a Double Empathy Framework

Recent research substantiates the Double Empathy Problem, revealing that breakdowns in communication frequently arise not from a singular ‘deficit’ within an individual, but from a reciprocal lack of understanding between neurotypical and neurodivergent people. Investigations demonstrate that difficulties aren’t solely experienced by autistic individuals when interacting with neurotypical counterparts; rather, neurotypical individuals also struggle to accurately interpret autistic communication styles, and vice versa. This bidirectional challenge stems from differing cognitive and communicative patterns, where each group operates with distinct, yet equally valid, sets of assumptions about social cues and conversational norms. The findings suggest that effective communication requires both parties to actively bridge these differences, shifting the focus from identifying impairments to fostering mutual understanding and adaptation – a perspective with significant implications for interpersonal interactions and the design of inclusive technologies.

Investigations utilizing bias detection methods within the system revealed a concerning tendency for the Large Language Model (LLM) to contribute to misinterpretations and, crucially, to reinforce pre-existing societal stereotypes. The analysis pinpointed specific instances where the LLM’s internal biases – shaped by the data it was trained on – led to skewed understandings of communication patterns, particularly those associated with neurodivergent individuals. This wasn’t simply a matter of inaccurate processing; the system actively amplified established prejudices, potentially leading to further marginalization. The findings demonstrate that AI, without careful calibration and ongoing scrutiny, risks perpetuating harmful biases instead of fostering genuine understanding and inclusive communication.

Conventional understandings of autism have historically centered on perceived deficits in social communication, framing neurological differences as impairments needing correction. However, recent research suggests this perspective is fundamentally flawed, instead proposing that communication difficulties arise not from an individual’s inherent inability, but from a mismatch in communicative styles between neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. This shift acknowledges that both groups operate with distinct cognitive and communicative frameworks, leading to reciprocal misunderstandings rather than a one-sided deficit. Embracing this nuanced understanding of neurodiversity necessitates moving beyond attempts to ‘normalize’ autistic communication and, instead, focusing on fostering mutual understanding and adapting communication strategies to bridge these differences – a perspective with profound implications for social inclusion and equitable interaction.

The principles underpinning the Double Empathy Problem have far-reaching consequences for the design of artificial intelligence. Current AI systems, frequently trained on datasets reflecting neurotypical communication patterns, risk perpetuating misinterpretations when interacting with neurodivergent individuals – and vice versa. Recognizing communication as a bidirectional process necessitates a shift towards AI development that actively accounts for diverse cognitive and communicative styles. This includes incorporating varied datasets, implementing bias detection methods, and prioritizing reciprocal intelligibility in AI design. Ultimately, a double empathy-informed approach promises not only more inclusive AI for neurodivergent users, but also systems that are fundamentally more robust, adaptable, and equitable for all individuals, fostering genuine understanding across cognitive differences.

The research meticulously distills the complexities of social interaction, revealing how even advanced language models can perpetuate harmful stereotypes. This echoes Alan Turing’s sentiment: “We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.” The study’s findings, exposing the model’s tendency to frame autistic individuals as reliant on neurotypical assistance, highlights the ‘short distance’ remaining in achieving truly unbiased AI. It’s a stark reminder that simply generating human-like text doesn’t equate to understanding the nuances of neurodiversity or overcoming the inherent biases embedded within training data. The work, therefore, advocates for a parsimonious approach – stripping away assumptions to reveal the core communication differences at play, rather than obscuring them with deficit-based narratives.

What Remains to Be Seen

The demonstration of subtly reinforced dependency narratives within a large language model is not, in itself, surprising. Models reflect the structures of the data upon which they are trained; the persistence of deficit-based assumptions regarding autism simply mirrors prevailing societal biases. The utility of this work lies not in the discovery of bias-that was a foregone conclusion-but in the articulation of a methodology for its elicitation. Further refinement of multi-agent simulations, however, must address the inherent limitations of reducing complex social interaction to quantifiable metrics. The current approach illuminates what the model portrays, but offers little insight into why.

A crucial next step involves expanding the scope of inquiry beyond the identification of biased outputs. It is insufficient to merely demonstrate that a model fails to recognize reciprocal communication differences; the research must investigate the underlying architectural factors that contribute to this failure. Does the model’s reliance on statistical co-occurrence, for example, inherently privilege dominant communication patterns? Or is the problem rooted in the representational capacity of the model itself?

Ultimately, the pursuit of “unbiased” artificial intelligence is a category error. All representation is, by definition, selective. A more productive endeavor lies in developing models that are transparently biased-models that explicitly acknowledge their limitations and allow for critical interrogation of their outputs. Clarity, after all, is compassion for cognition.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15437.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- YouTuber streams himself 24/7 in total isolation for an entire year

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Lacari banned on Twitch & Kick after accidentally showing explicit files on notepad

- Ragnarok X Next Generation Class Tier List (January 2026)

- Shameless is a Massive Streaming Hit 15 Years Later

- ‘That’s A Very Bad Idea.’ One Way Chris Rock Helped SNL’s Marcello Hernández Before He Filmed His Netflix Special

- Beyond Agent Alignment: Governing AI’s Collective Behavior

- ZCash’s Bold Comeback: Can It Outshine Bitcoin as Interest Wanes? 🤔💰

- XDC PREDICTION. XDC cryptocurrency

- We Need to Talk About Will

2026-01-24 02:15