Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework leverages the power of physics-informed neural networks to accurately simulate and invert viscoacoustic wave propagation, even with limited data.

This review details a physics-informed neural network approach for forward modeling, inversion, and sensitivity analysis of viscoacoustic wave propagation, demonstrating robustness to discretization.

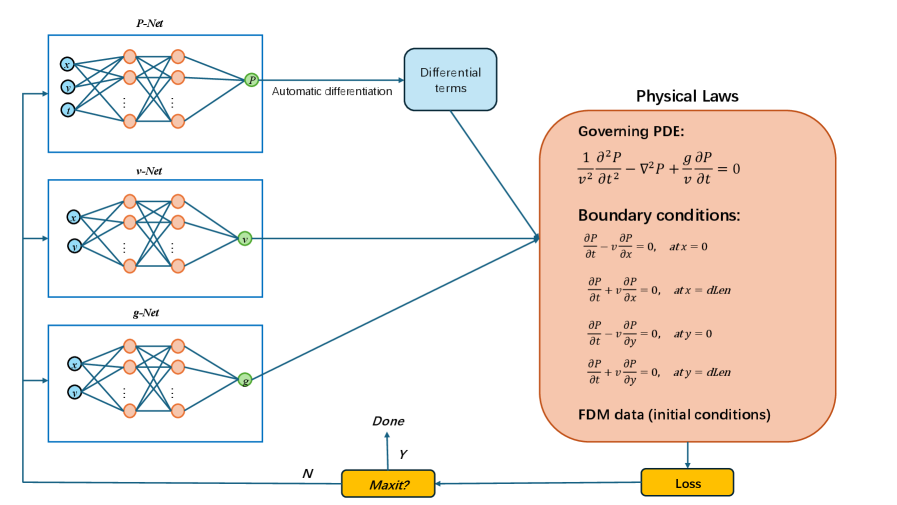

Conventional numerical methods for seismic wave propagation often demand computationally expensive dense discretizations and numerous forward simulations, particularly in inverse problems. This study, detailed in ‘Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Viscoacoustic Wave Propagation: Forward Modelling, Inversion and Discretization Sensitivity’, introduces a physics-informed neural network (PINN) framework capable of accurately modeling and inverting viscoacoustic wavefields while simultaneously estimating velocity and attenuation parameters. By embedding the governing wave equation directly into the learning process, the proposed approach demonstrates robust performance and reduced sensitivity to spatial discretization compared to finite-difference solutions. Could this data-efficient and physically consistent methodology offer a pathway towards high-resolution seismic imaging in complex attenuative media?

The Illusion of Solidity: Modeling Earth’s Depths

The Earth’s subsurface is not simply a collection of perfectly elastic solids; instead, materials exhibit both the ability to store and release mechanical energy – elasticity – and a tendency to dissipate that energy through internal friction, known as viscosity. Accurately modeling seismic wave propagation, crucial for applications like earthquake monitoring and resource exploration, therefore necessitates considering both properties. While the elastic wave equation provides a foundational understanding, it often fails in complex geological settings where materials like shale, saturated sediments, and partially molten rock exhibit significant viscous behavior. This dissipation of energy, influenced by factors like fluid content and rock composition, impacts wave amplitude, velocity, and even the very shape of the wave as it travels through the Earth. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of subsurface wave behavior requires models that account for these combined elastic and viscous characteristics, allowing for more realistic and reliable predictions of seismic events and improved interpretations of subsurface structures.

The conventional elastic wave equation, while effective in simplified geological models, frequently proves inadequate when applied to the complexities of the Earth’s subsurface. This limitation arises because real-world materials aren’t perfectly elastic; they exhibit varying degrees of attenuation and dispersion due to internal friction and material relaxation processes. Consequently, the simple spring-mass analogy underpinning the elastic equation fails to capture the full spectrum of wave behavior observed in heterogeneous and lossy media. Seismic waves lose energy as they propagate through such materials, and different frequency components travel at different speeds – phenomena the elastic equation cannot predict. A more comprehensive modeling approach, therefore, becomes essential for accurate seismic imaging and interpretation, particularly in scenarios involving fractured rocks, fluids, or fine-grained sediments, where these effects are pronounced.

The viscoacoustic wave equation represents a significant advancement in modeling wave propagation through complex media by moving beyond the limitations of purely elastic treatments. Unlike elastic models which assume instantaneous return to an original shape, the viscoacoustic framework explicitly incorporates material relaxation-the time it takes for a material to respond to stress-and, crucially, energy dissipation. This dissipation accounts for the conversion of wave energy into heat due to internal friction within the material, a process prominent in Earth’s subsurface. The equation achieves this by introducing frequency-dependent parameters that describe how materials respond differently to varying wave frequencies, allowing for more realistic simulations of wave attenuation and dispersion. Consequently, viscoacoustic modeling proves essential for accurate seismic imaging, particularly in scenarios involving fine-grained sediments, fractured rocks, or fluids, where viscous effects dominate and traditional elastic approaches fail to capture the true behavior of waves. \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial t^2} + 2\gamma \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \omega^2 u = c^2 \nabla^2 u represents a simplified form, where γ is a damping coefficient, ω is the angular frequency, and c is the wave speed.

The Fabric of Resistance: A Maxwellian View

The Maxwell model represents viscoelastic material behavior by combining a purely elastic component, modeled as a spring with modulus μ, in series with a purely viscous dashpot exhibiting viscosity η. This series configuration dictates that the total strain is the sum of the strain in the spring and the strain rate multiplied by time in the dashpot. Consequently, the model predicts immediate elastic response followed by delayed, time-dependent viscous flow under sustained stress. The combined effect accurately simulates the behavior of subsurface materials which exhibit both elastic recovery and irreversible deformation under stress, unlike purely elastic or viscous materials. This combination is mathematically expressed as \sigma + \eta \frac{d\epsilon}{dt} = \mu \epsilon , where σ is stress and ε is strain.

The Maxwell model’s ability to represent time-dependent deformation and relaxation is fundamental to accurately simulating wave propagation in viscoelastic media. Unlike purely elastic materials which respond instantaneously to stress, the Maxwell model incorporates a viscous component – a dashpot – that introduces a delay in the material’s response. This delay manifests as creep – continued deformation under constant stress – and stress relaxation – a decrease in stress under constant strain. These effects are critical because subsurface materials exhibit these behaviors, and ignoring them leads to inaccuracies in seismic modeling, particularly at lower frequencies where viscous effects are more pronounced. The time-dependent response captured by the model impacts both the velocity and attenuation of seismic waves, influencing travel times and signal amplitudes, and thus the interpretation of subsurface structures. \sigma + \tau \frac{d\epsilon}{dt} = E\epsilon mathematically describes this relationship, where σ is stress, ε is strain, τ is viscosity, and E is Young’s modulus.

The viscoacoustic wave equation is derived from the Maxwell model by applying force balance equations to the spring and dashpot components and relating stress to strain rate through the model’s constitutive law. Specifically, the Maxwell model defines stress as the sum of an instantaneous elastic component and a time-dependent viscous component; mathematically, \sigma(t) = E\epsilon(t) + \eta \frac{d\epsilon(t)}{dt} , where σ is stress, ε is strain, E is Young’s modulus, and η is viscosity. Applying this relationship, alongside Newton’s second law and the continuity equation, results in a hyperbolic partial differential equation describing wave propagation in viscoelastic media; this equation accounts for both pressure (P) and velocity (v) fields, effectively modeling the attenuation and dispersion characteristics observed in subsurface materials due to their inherent viscoelastic properties.

Echoes in the Void: Solving the Wave Equation

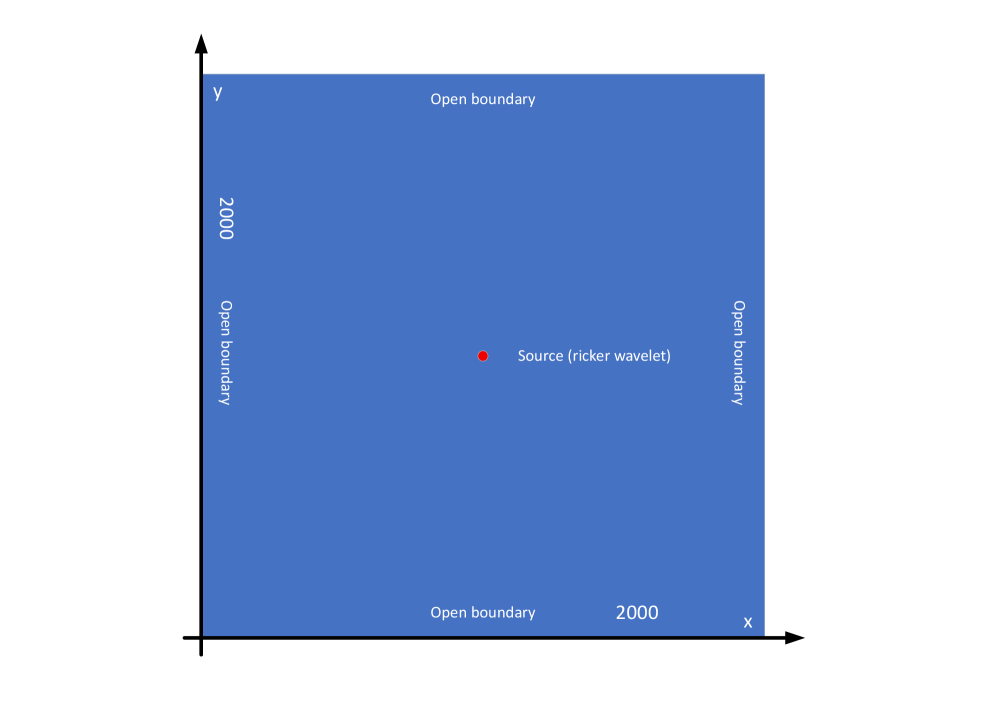

The simulation of wave propagation is achieved through the application of the viscoacoustic wave equation, a partial differential equation describing wave motion in media exhibiting both elastic and viscous properties. As a seismic source, the Ricker wavelet – a second derivative of a Gaussian function – is employed due to its minimal phase characteristics and its spectral similarity to seismic events. The Ricker wavelet is mathematically defined as f(t) = (1 - 2\pi^2 f^2 t^2)e^{- \pi^2 f^2 t^2} , where f represents the dominant frequency. Utilizing this wavelet as an input signal allows for the controlled generation of seismic waves within the modeled environment, enabling the analysis of wave behavior as it propagates through complex geological structures.

Open boundary conditions, often implemented through absorbing layers or perfectly matched layers (PMLs), are critical in numerical wave propagation simulations to prevent spurious reflections from the computational domain’s edges. Without these conditions, energy reaching the boundaries would reflect back into the modeled area, distorting the wavefield and leading to inaccurate results. These conditions work by gradually absorbing the energy of outgoing waves, effectively simulating an infinitely large domain. The effectiveness of open boundary conditions is assessed by minimizing the reflection coefficient R at the boundaries, ideally achieving R \approx 0. Incorrect implementation or insufficient boundary extent can still cause noticeable artifacts in the simulated wavefield, particularly at lower frequencies.

The implemented viscoacoustic wave equation setup facilitates the quantitative analysis of wave propagation characteristics in media exhibiting attenuation and dispersion. Attenuation, representing the energy loss of the wave as it propagates, is modeled through the frequency-dependent absorption coefficient incorporated into the viscoacoustic equation. Dispersion, the velocity variation with frequency, arises from the media’s viscoelastic properties and is inherently accounted for by the constitutive relation used in the wave equation. By varying the parameters defining these properties – shear and bulk moduli, viscosity – the impact on wave amplitude decay and phase velocity can be systematically investigated, allowing for the characterization of complex geological materials and the validation of numerical modeling techniques against observational data.

The Illusion of Knowing: Reconstructing the Subsurface

Determining the hidden architecture beneath the Earth’s surface represents a core challenge in geophysics, addressed through the ‘inverse problem’. This involves inferring the velocity structure of subsurface layers – how quickly seismic waves travel through different materials – based solely on the seismic data recorded at the surface. Essentially, scientists analyze the patterns of reflected and refracted waves to ‘image’ the underground, much like a medical scan reveals internal organs. This is a complex undertaking, as numerous subsurface configurations can produce the same observed seismic signals, leading to ambiguity. Solving the inverse problem requires sophisticated mathematical techniques and computational models to navigate this uncertainty and build a reliable picture of what lies beneath, with implications ranging from resource exploration to earthquake hazard assessment.

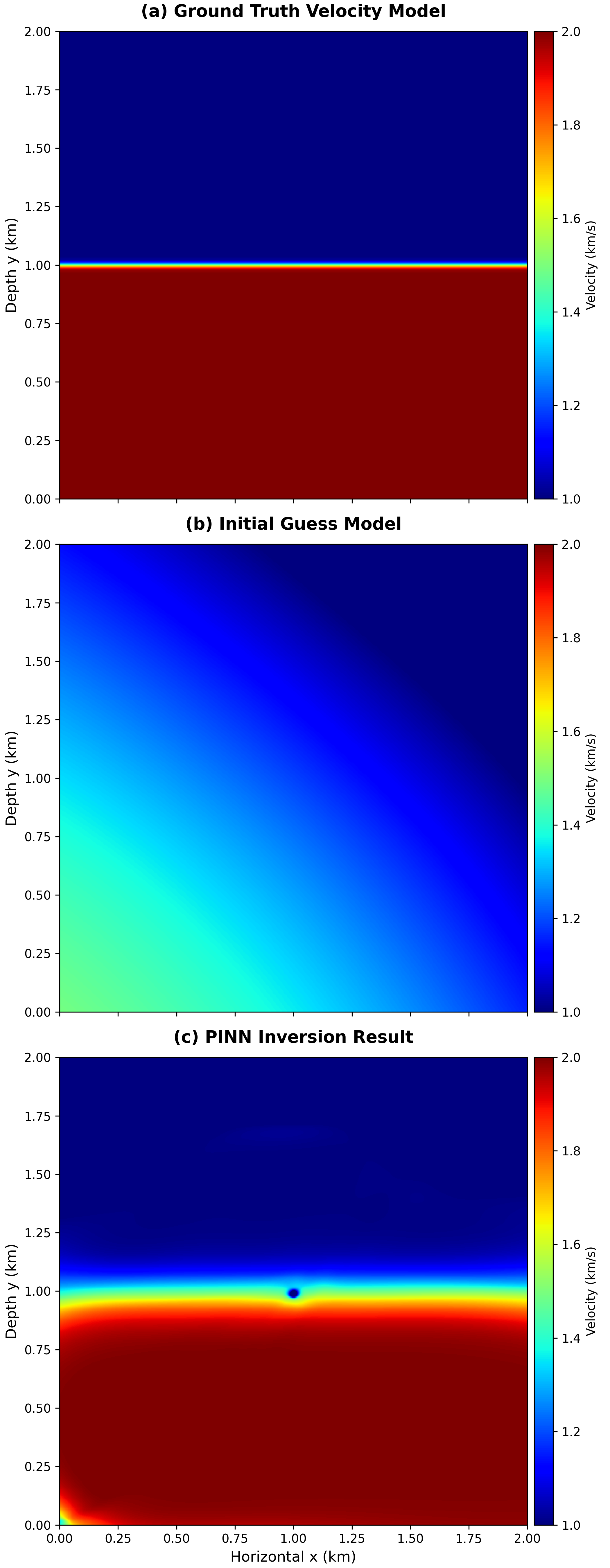

The estimation of subsurface properties begins with a simplified two-layer velocity model, serving as a foundational approximation of the Earth’s complex structure. To account for the inherent uncertainty and variability of real-world geological formations, the research employs stochastic initial models – essentially, a range of randomly generated starting points – to comprehensively explore the vast solution space. This approach allows the system to avoid becoming trapped in local minima and increases the likelihood of identifying a globally optimal solution, ultimately providing a more robust and accurate reconstruction of the subsurface velocity structure. By systematically sampling numerous initial conditions, the method effectively maps out the potential range of plausible models, enhancing the reliability and interpretability of the results.

The reconstruction of attenuation coefficients, crucial for understanding subsurface properties, benefits significantly from a physics-informed neural network (PINN) framework. This approach achieves a relative error of only 19.05%, representing a marked improvement over conventional methods. Notably, the PINN demonstrates robust stability even when utilizing coarse discretization – a condition that frequently causes traditional techniques, such as Finite Difference Methods which yielded a relative error of 58.01%, to fail dramatically. This resilience suggests the PINN offers a more reliable pathway to accurately characterizing subsurface features, potentially unlocking new levels of detail in seismic analysis and interpretation.

The pursuit of accurate wave propagation modeling, as demonstrated by this work on physics-informed neural networks, often resembles building elaborate structures near the edge of a precipice. Each refinement to the PINN framework, each attempt to improve inversion robustness, is a step further, yet the fundamental challenge – reconciling model with observed reality – persists. As Richard Feynman observed, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.” This sentiment resonates with the authors’ careful consideration of discretization sensitivity; a seemingly minor detail can undermine the entire edifice, highlighting the need for constant vigilance against self-deception in scientific inquiry. The presented framework, while promising, remains subject to the limitations inherent in any attempt to capture the complexities of the physical world.

Where Do the Ripples Lead?

This work, applying neural networks constrained by the familiar scaffolding of physics, offers a predictable improvement in forward modeling and inversion. It’s a neat trick, achieving stability with limited data – a common refrain in any field where reality refuses to cooperate. Yet, one suspects the true test isn’t whether the network can model viscoacoustic wave propagation, but whether it reveals anything genuinely new about it. Physics is the art of guessing under cosmic pressure, and these networks are, at their core, exceptionally sophisticated guessing machines.

The real limitations, as always, lie not in the method, but in the assumptions baked into the physics itself. Attenuation models, discretization schemes – these are approximations, elegant fictions imposed on a universe that rarely cares for elegance. Future work will undoubtedly refine the network architecture, explore different loss functions, and boast of ever-increasing accuracy. But a more fruitful path may lie in deliberately breaking the physics, in allowing the network to wander beyond the well-lit paths of established theory.

Because let’s be clear: any model, no matter how cleverly constructed, is vulnerable. A single unexpected data point, a subtle anomaly, and the whole edifice can crumble. The event horizon isn’t just around black holes; it surrounds every theory. The question isn’t whether this network will succeed, but what will be revealed when – not if – it fails.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16068.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- YouTuber streams himself 24/7 in total isolation for an entire year

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Shameless is a Massive Streaming Hit 15 Years Later

- ‘That’s A Very Bad Idea.’ One Way Chris Rock Helped SNL’s Marcello Hernández Before He Filmed His Netflix Special

- Lacari banned on Twitch & Kick after accidentally showing explicit files on notepad

- Ragnarok X Next Generation Class Tier List (January 2026)

- A Duet of Heated Rivalry Bits Won Late Night This Week

- ZCash’s Bold Comeback: Can It Outshine Bitcoin as Interest Wanes? 🤔💰

- Binance Wallet Dives into Perpetual Futures via Aster-Is This the Future? 🤯

- Ex-Rate My Takeaway star returns with new YouTube channel after “heartbreaking” split

2026-01-23 17:49