Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how inherent properties of changing systems can signal impending transitions, even without a clear tipping point, offering insights for forecasting in fields like epidemiology.

This study utilizes linear noise approximation and time-dependent covariance analysis to identify early warning signals in stochastic dynamical systems, focusing on non-critical transitions in epidemic models.

Predicting transitions in complex systems often relies on identifying bifurcations, yet fluctuations can signal change even without a clear tipping point. This is the central question addressed in ‘Early warning signals of non-critical transitions from linearised time-varying dynamics with applications to epidemic systems’, which demonstrates that geometric properties of dynamical systems-specifically, those arising from non-normal operators-can generate early warning signals akin to critical slowing down. By analyzing fluctuations around the mean in stochastic systems-illustrated using a susceptible-infectious-recovered model-this work reveals how infection waves can be anticipated without requiring an equilibrium bifurcation. Could these findings offer a more robust framework for forecasting transitions in a wider range of complex, time-varying systems?

Beyond Static Stability: Recognizing the Limits of Traditional Analysis

Classical stability analyses, while foundational in many engineering disciplines, frequently operate under the assumption of time-invariant systems – a simplification that often clashes with the realities of the physical world. This approach presumes that a system’s properties remain constant over time, neglecting the influence of evolving parameters, external disturbances, and internal drifts. Consequently, these analyses can fail to accurately predict system behavior when confronted with even minor variations, such as material fatigue, temperature fluctuations, or changing operational conditions. The inherent limitations of this static viewpoint mean that predictions based solely on time-invariant models may not hold true in dynamic environments, potentially leading to unforeseen instabilities or suboptimal performance. A more nuanced understanding, accounting for temporal changes, is therefore essential for robust and reliable system design and control.

The assumption of unwavering stability in many analytical models neglects a critical reality: even minute disturbances can significantly alter a system’s trajectory. These seemingly insignificant perturbations, often dismissed as noise, can be amplified by the system’s inherent dynamics, leading to deviations from predicted behavior. This is particularly true in complex systems where interactions between components can create sensitivities to initial conditions. Consequently, predictions based solely on an idealized, undisturbed state can prove inaccurate, potentially undermining control strategies and creating unforeseen consequences. A thorough understanding of how systems respond to these small, yet influential, perturbations is therefore essential for robust modeling and reliable forecasting.

A system’s initial reaction to disturbances, known as its transient response, dictates its immediate behavior and is therefore critical for accurate prediction and effective control. While traditional stability analyses focus on long-term equilibrium, they often neglect these crucial initial dynamics, potentially overlooking vulnerabilities to even minor perturbations. Understanding the transient phase reveals how quickly a system settles – or fails to settle – into a desired state, providing insights into its resilience and responsiveness. This is particularly important in complex systems where interactions can amplify initial disturbances, making the transient response a key indicator of overall system health and a fundamental component of robust control strategies. Ignoring these initial behaviors can lead to flawed predictions and ultimately, system failure, highlighting the necessity of prioritizing transient analysis for reliable performance.

Conventional analytical techniques often fall short when predicting the behavior of systems exhibiting transient dynamics, especially those categorized as non-normal. These systems, unlike normal systems where initial disturbances decay predictably, can amplify certain perturbations over time, leading to unexpected and potentially unstable outcomes. The difficulty arises because traditional methods rely on assumptions about system behavior that don’t hold true for non-normal systems – specifically, that the system’s response can be adequately described by its eigenvectors. Instead, the initial transient phase is governed by a complex interplay of numerous modes, each with its own decay rate and spatial structure, making accurate characterization challenging. Consequently, predictions based on classical stability analyses can be misleading, highlighting the need for advanced tools capable of capturing these complex, time-dependent phenomena and ensuring reliable system control.

Tools for Unveiling Transient Responses: Characterizing System Dynamics

The Jacobian matrix, denoted as J, represents the first-order partial derivatives of a system of nonlinear differential equations evaluated at a fixed point x_0. This linearization allows for the approximation of system behavior in a localized region around x_0. Local stability is then determined by analyzing the eigenvalues of J; if all eigenvalues have negative real parts, the fixed point is locally asymptotically stable. Conversely, a positive real part in any eigenvalue indicates local instability. The matrix provides a means to assess how infinitesimal perturbations around the fixed point will evolve over time, offering insight into the system’s responsiveness to disturbances near that operating point. This analysis assumes that the linearized approximation is valid, typically requiring perturbations to remain sufficiently small.

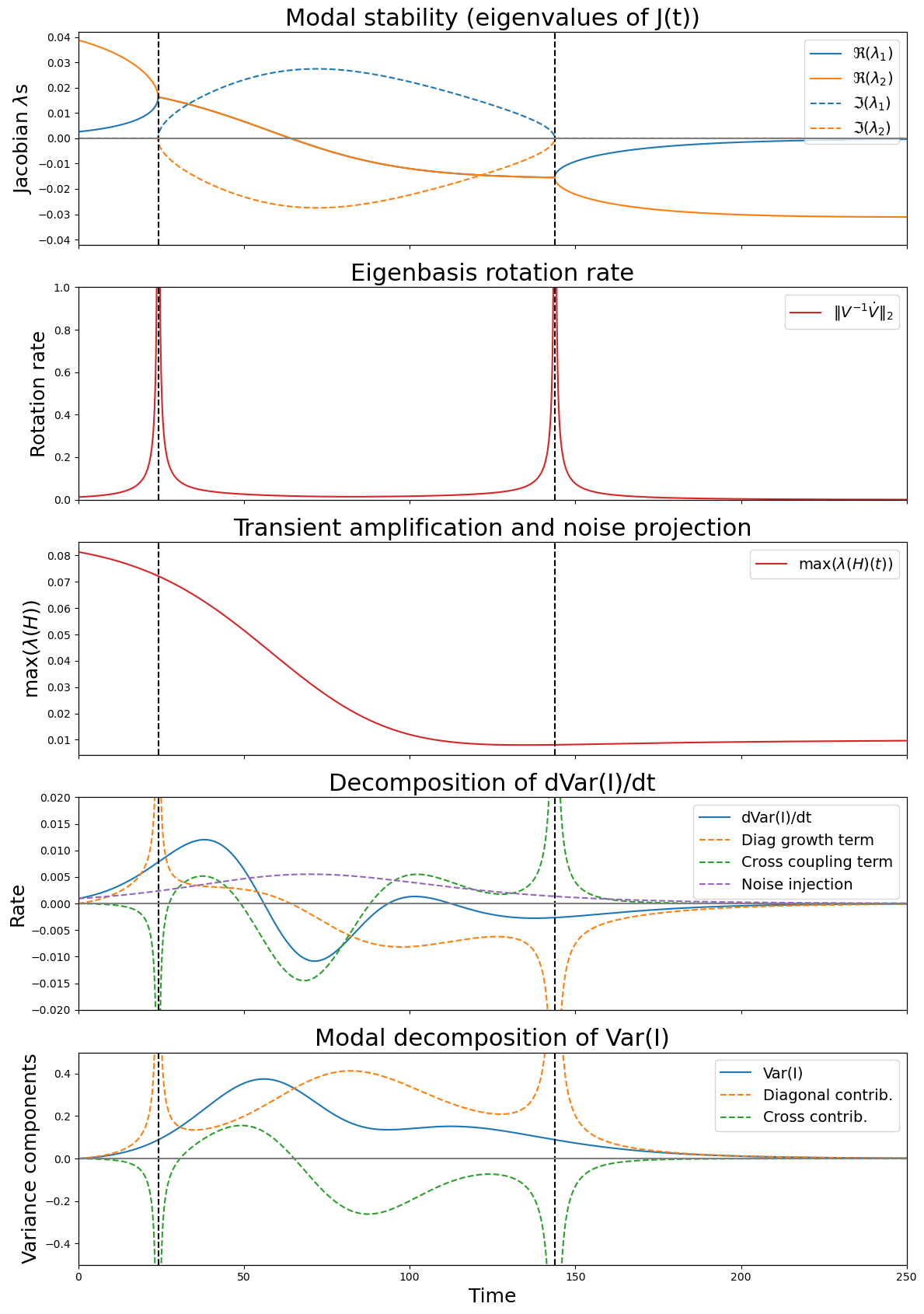

Spectral analysis of the Jacobian matrix provides insights into system behavior through its eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The real part of an eigenvalue directly correlates with the rate at which a system returns to equilibrium after a perturbation; negative real parts indicate stability and exponential decay, while positive real parts signify instability and potential divergence. Critically, even with stable eigenvalues (negative real parts), the magnitude of the real part influences the rate of return to equilibrium, which is directly linked to critical slowing down – a phenomenon where the system responds sluggishly to changes near a critical point. Furthermore, the variance of fluctuations in the system is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the negative real part of the dominant eigenvalue; smaller (less negative) real parts indicate larger fluctuations and increased sensitivity to perturbations. \text{Variance} \propto \frac{1}{|Re(\lambda_{dominant})|} .

In non-normal systems, the standard eigenvalue analysis of the Jacobian matrix, while indicating stability, can be misleading; transient amplification of initial perturbations can significantly influence system behavior. This occurs because the eigenvectors are not orthogonal, allowing for temporary growth of certain perturbation modes even if all eigenvalues have negative real parts, ensuring ultimate stability. The magnitude of this transient growth is quantified by the norm of the Jacobian, and can dominate the system’s response for a considerable period before decaying towards the stable fixed point. Consequently, assessing system dynamics in non-normal systems requires methods that go beyond simply examining the eigenvalues, such as examining the system’s response to specific initial conditions or employing techniques to quantify the transient amplification directly.

The Time-Dependent Lyapunov Equation (TDLE) provides a means to model the evolution of the system’s Covariance Matrix, P(t), which quantifies the spread of initial perturbations over time. This equation, expressed generally as \dot{P} = AP + PA - P\Gamma P, where A represents the system matrix, P is the Covariance Matrix, and Γ accounts for noise, allows for the calculation of perturbation growth rates and spatial structures. Analysis of the TDLE reveals that the system’s spectra – the eigenvalues of A – and pseudo-spectra, which characterize the local behavior of the resolvent, fundamentally govern the evolution of P(t). Specifically, the eigenvalues dictate the exponential decay or growth of individual perturbation modes, while the pseudo-spectrum influences the transient amplification of perturbations and the overall rate of critical slowing down, even in systems with stable eigenvalues.

Anticipating Instability: Identifying Early Warning Signals

Critical slowing down refers to the increase in recovery time following a perturbation as a system approaches an instability point. This manifests as a decrease in the rate at which the system returns to equilibrium after being displaced from its stable state. Quantitatively, this is observed as an increasing autocorrelation time or a decreasing spectral bandwidth of the system’s response. The magnitude of this slowing is often proportional to the distance from the instability, making it a measurable indicator of increasing vulnerability. This phenomenon isn’t limited to simple bifurcations; it can also precede transitions driven by more complex dynamics, providing a crucial early warning signal for potential system failure.

Spectral analysis, specifically examining the eigenvalues of the system’s Jacobian matrix, provides a quantifiable method for detecting critical slowing down. A shift in the spectral properties, notably the approach of eigenvalues towards the imaginary axis, directly correlates with decreasing relaxation rates and increasing system vulnerability. The imaginary part of the leading eigenvalue is inversely proportional to the relaxation timescale; therefore, a reduction in this value indicates a slowing of the system’s return to equilibrium after perturbation. This allows for the calculation of a warning signal – typically the inverse of the leading eigenvalue’s imaginary component – which serves as a proxy for the time remaining before a potential instability event. The magnitude of this spectral measure provides a quantitative assessment of the system’s proximity to a critical transition.

Early warning signals for instability traditionally focus on bifurcations, points where a system’s qualitative behavior changes. However, these signals also arise from pseudo-bifurcations induced by non-normal operators. Non-normal operators, unlike normal operators, do not possess a complete set of orthonormal eigenvectors, leading to transient growth of perturbations even in stable systems. This transient growth manifests as changes in relaxation rates detectable through spectral analysis, mimicking the behavior observed at true bifurcations. Consequently, identifying these signals allows for the prediction of instability even in systems where the underlying dynamics are not characterized by abrupt qualitative shifts, but rather by sustained, albeit potentially subtle, changes in behavior driven by the influence of non-normal operators.

The ability to detect critical slowing down and related spectral changes enables the prediction of complex system shifts prior to catastrophic failure events. This predictive capability stems from the observation that as a system approaches an instability point, its return rate to equilibrium decreases, manifesting as a lengthening of relaxation times and a corresponding shift in the system’s spectral properties. By monitoring these changes – quantifiable through techniques like spectral analysis – it is possible to identify increasing vulnerability and anticipate qualitative changes in system behavior, even in cases involving non-normal operators and pseudo-bifurcations, effectively providing an early warning system before irreversible transitions occur.

From Theory to Real-World Impact: Modeling Complex Systems

The susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model stands as a foundational tool in epidemiology, offering a simplified yet powerful framework for understanding and predicting the spread of infectious diseases. At its heart lies the concept of the effective reproduction number, R_t, which represents the average number of new infections caused by a single infected individual at time t. When R_t exceeds one, the disease will spread, with each infected person causing more than one new infection; conversely, if R_t falls below one, the disease will eventually die out. This number isn’t a fixed property of the pathogen, but rather dynamically changes based on factors like population density, contact rates, and public health interventions. By carefully estimating and monitoring R_t, epidemiologists can gain critical insights into the trajectory of an outbreak and inform strategies to mitigate its impact, such as vaccination campaigns or social distancing measures.

The inherent randomness present in many complex systems, from gene expression to population dynamics, often necessitates going beyond deterministic modeling. Linear Noise Approximation (LNA) provides a powerful analytical technique to address this challenge by calculating the Quasi-Stationary Distribution (QSD). This distribution effectively captures the long-term stochastic behavior of the system, revealing not just the average trends, but also the likely range of fluctuations around those averages. Unlike simulations which can be computationally expensive, LNA offers an efficient method for approximating the QSD, providing insights into the system’s resilience, potential tipping points, and the probability of rare events. The technique relies on characterizing the noise in system parameters and then solving a modified system of equations to determine the QSD, offering a tractable approach to understanding complex, fluctuating phenomena without requiring exhaustive computational exploration.

Traditional epidemiological models often present a deterministic view of disease spread, predicting a single, inevitable outcome. However, real-world outbreaks are invariably subject to chance events – a superspreader unknowingly infecting a disproportionate number of individuals, or localized variations in population density impacting transmission rates. By incorporating stochasticity – inherent randomness – into these models, researchers can move beyond simple predictions and generate a more nuanced, realistic picture of how diseases actually spread. These advanced techniques, like those employing the Linear Noise Approximation, don’t just forecast whether an outbreak will occur, but also provide insight into the range of possible outcomes and the likelihood of each. This is crucial for public health planning, allowing for the development of strategies that are robust to unpredictable fluctuations and better equipped to mitigate the impact of even low-probability, high-consequence events.

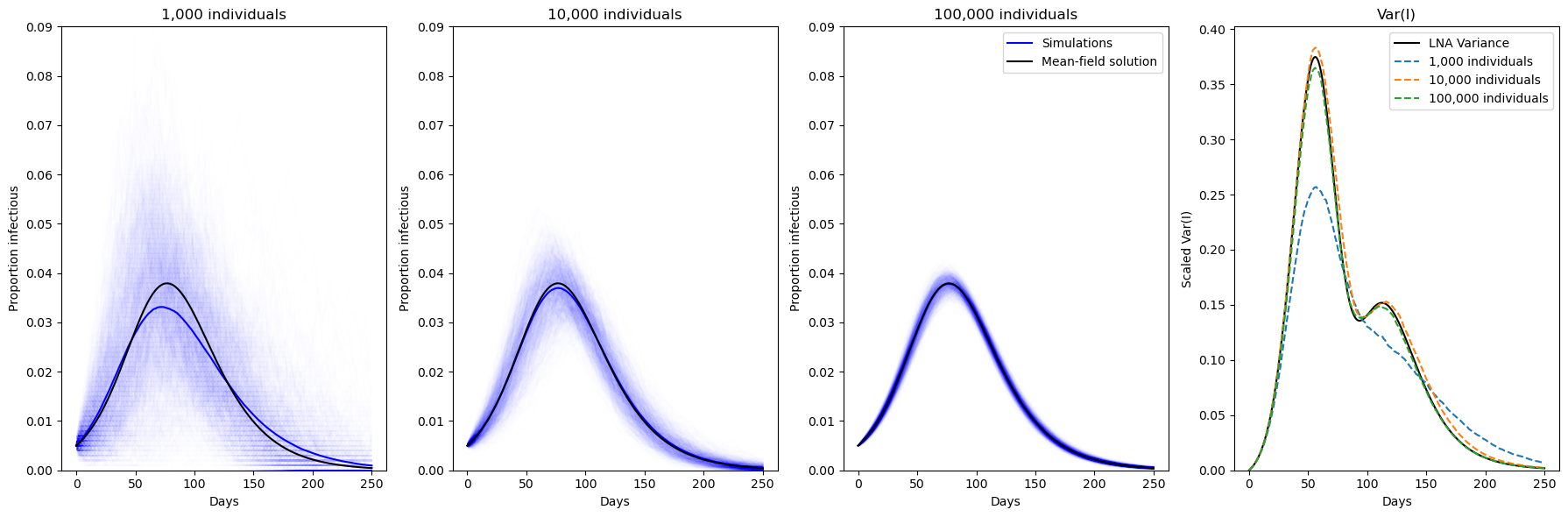

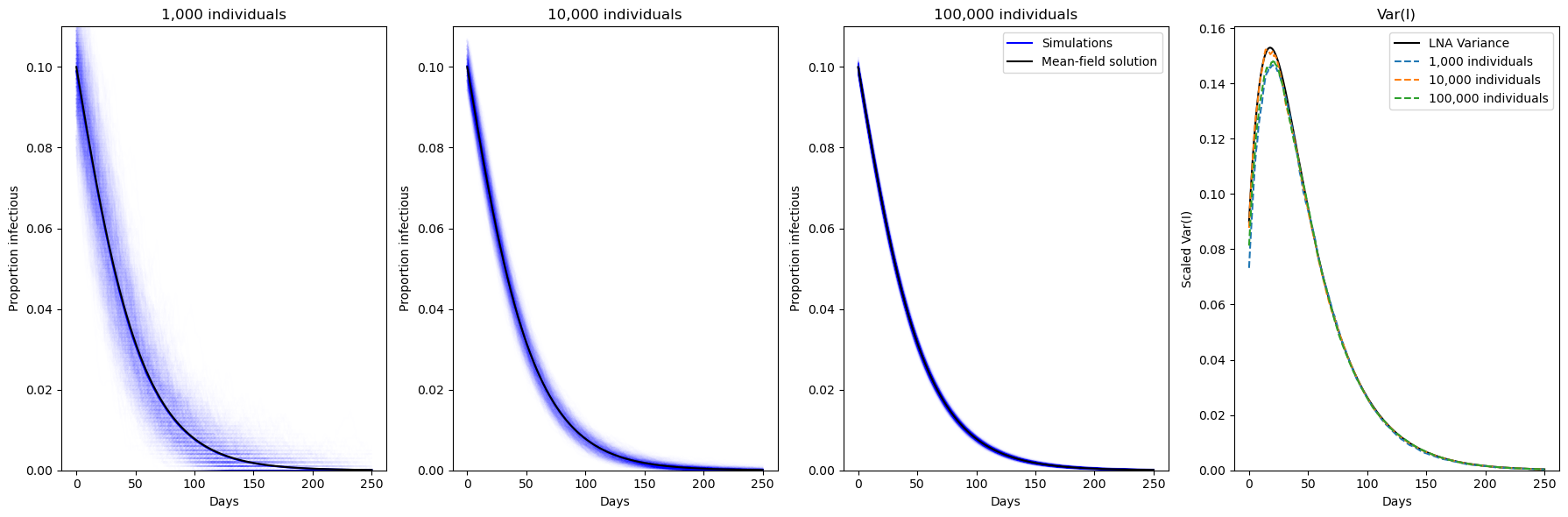

Gillespie simulations served as a crucial validation step for the developed theoretical framework, revealing strong agreement between predicted fluctuations and simulation results, especially as population sizes increased. This concordance confirms the accuracy of the approach in modeling stochastic dynamics within complex systems. Furthermore, the simulations provided quantitative bounds on these fluctuations, directly linked to the minimum and maximum eigenvalues of the symmetric Jacobian. These eigenvalues effectively define the range within which stochastic variations are expected to occur, offering a powerful tool for understanding and predicting the behavior of systems where randomness plays a significant role – from disease spread to population genetics and beyond. The ability to theoretically derive these bounds, and then confirm them through simulation, establishes a robust methodology for analyzing the inherent uncertainties within complex systems.

The study rigorously establishes a framework for discerning shifts in dynamical systems not through catastrophic bifurcations, but via subtle alterations in time-varying characteristics. This approach, focusing on geometric properties and the analysis of time-dependent covariance, reveals fluctuations indicative of approaching transitions. It echoes Galileo Galilei’s sentiment: “You can know how the universe works by examining its effects.” The research, much like Galileo’s observations, prioritizes empirical evidence-in this case, quantifiable fluctuations-to understand underlying systemic changes. The work moves beyond simply identifying critical points, instead emphasizing the potential for early detection through careful monitoring of evolving dynamics.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of predictive capability in dynamical systems frequently fixates on the precipice of change – the bifurcation. This work suggests a more subtle, and perhaps more realistic, path: recognizing shifts before they necessitate a categorical redefinition of stability. The demonstrated link between time-dependent covariance and emergent system behavior, independent of critical slowing down, offers a means to detect subtle geometric distortions within the state space – signals previously obscured by an overreliance on static analyses. However, the reliance on linearised approximations remains a constraint. The question is not simply whether these signals exist, but their robustness when confronted with the inherent non-linearities of complex systems.

Future work must address the extension of these geometric diagnostics beyond simplified models. Application to high-dimensional systems, particularly those lacking a clear, low-dimensional representation, presents a significant challenge. Furthermore, the translation of these theoretical signals into actionable intelligence requires careful consideration of noise and imperfect observation – the real world rarely offers the pristine data assumed by many analytical frameworks. The art, it seems, will be not in detecting the signal, but in distilling it from the entropy.

Ultimately, the field should move beyond merely anticipating transitions. A truly useful theory will not simply announce impending change, but will characterize the nature of that change – its direction, its magnitude, and its potential impact. The current framework offers a promising, parsimonious approach to early warning, but its full potential will only be realised when it can move beyond diagnosis, and offer something approaching prognosis.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.14869.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- XDC PREDICTION. XDC cryptocurrency

- RIVER Coin’s 1,200% Surge: A Tale of Hype and Hope 🚀💸

- Beyond Agent Alignment: Governing AI’s Collective Behavior

- Mark Ruffalo Finally Confirms Whether The Hulk Is In Avengers: Doomsday

- What time is Idol I Episode 9 & 10 on Netflix? K-drama release schedule

- Indiana Jones Franchise Future Revealed As Kathleen Kennedy Speaks Out

- Stephen King Is Dominating Streaming, And It Won’t Be The Last Time In 2026

- Arc Raiders Eyes On The Prize Quest Guide

- Mike Myers Sought Expert Help for His Elon Musk Impression

2026-01-22 13:23