Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages mixtures of transparent local models to create interpretable machine learning systems with guaranteed performance bounds.

This work introduces a PAC-Bayesian framework for constructing and analyzing mixtures of experts, offering risk bounds and enabling reliable predictions even for unseen data.

Despite the increasing prevalence of machine learning, ensuring model transparency remains a critical challenge, particularly regarding security and fairness. This paper introduces ‘Mixtures of Transparent Local Models’ as a novel approach to interpretable machine learning, constructing predictions from combinations of simple, locally-focused functions. By simultaneously learning both these transparent labeling functions and the regions of input space to which they apply, we establish rigorous PAC-Bayesian risk bounds for binary classification and regression tasks. Could this method unlock more reliable and understandable AI systems, especially in high-stakes applications?

The Illusion of Uniformity: Why Global Models Often Fail

Conventional machine learning frequently employs global models, built on the premise of consistent relationships throughout an entire dataset. This approach, while computationally efficient, operates under a simplification that can significantly hinder performance when faced with real-world complexity. The assumption of uniformity neglects the inherent heterogeneity often present in data – variations arising from differing contexts, local conditions, or evolving patterns. Consequently, a single, overarching model struggles to accurately capture the nuances within specific subsets of the data, leading to diminished predictive power and a failure to generalize effectively across diverse scenarios. The limitations of global models highlight the necessity for more adaptive techniques capable of recognizing and responding to localized data characteristics.

Traditional machine learning models frequently falter when confronted with datasets exhibiting significant heterogeneity, meaning variations across different subsets of the data. These global models assume consistent relationships throughout, a simplification that breaks down in complex scenarios where local nuances dominate. For instance, predicting housing prices requires considering neighborhood-specific factors-schools, crime rates, proximity to amenities-that a single, overarching model cannot adequately capture. Similarly, in medical diagnosis, patient responses to treatment can differ dramatically based on genetic predispositions or lifestyle, demanding localized predictive power. Consequently, the inability of these models to account for such local variations directly impacts prediction accuracy, highlighting the necessity for techniques that embrace and leverage the inherent diversity within complex datasets.

The pursuit of increasingly accurate predictive models has highlighted a critical limitation of traditional machine learning: its reliance on globally-defined relationships within data. Real-world datasets, however, are rarely uniform; instead, they exhibit significant local variations driven by underlying complexities. Consequently, a growing emphasis is placed on localized learning strategies – techniques designed to capture these nuanced data distributions. These approaches move beyond a single, overarching model to instead prioritize adaptability, allowing the model to refine its predictions based on the specific characteristics of each data subset. This shift represents a fundamental move toward more robust and reliable machine learning systems, capable of navigating the inherent heterogeneity of complex phenomena and delivering more precise results where global models fall short.

Deconstructing Complexity: A Paradigm of Local Expertise

The Mixture of Transparent Local Models addresses complex prediction tasks by decomposing them into multiple, smaller sub-problems, each focused on a specific segment of the input space. This decomposition contrasts with monolithic models attempting to learn a global mapping from input to output. By partitioning the problem, the model can leverage specialized solutions for each localized region, potentially improving overall accuracy and efficiency. This approach allows for the training of multiple models – the “local experts” – which are then combined to produce a final prediction, effectively creating a conditional model where the relevant expert is activated based on the input characteristics.

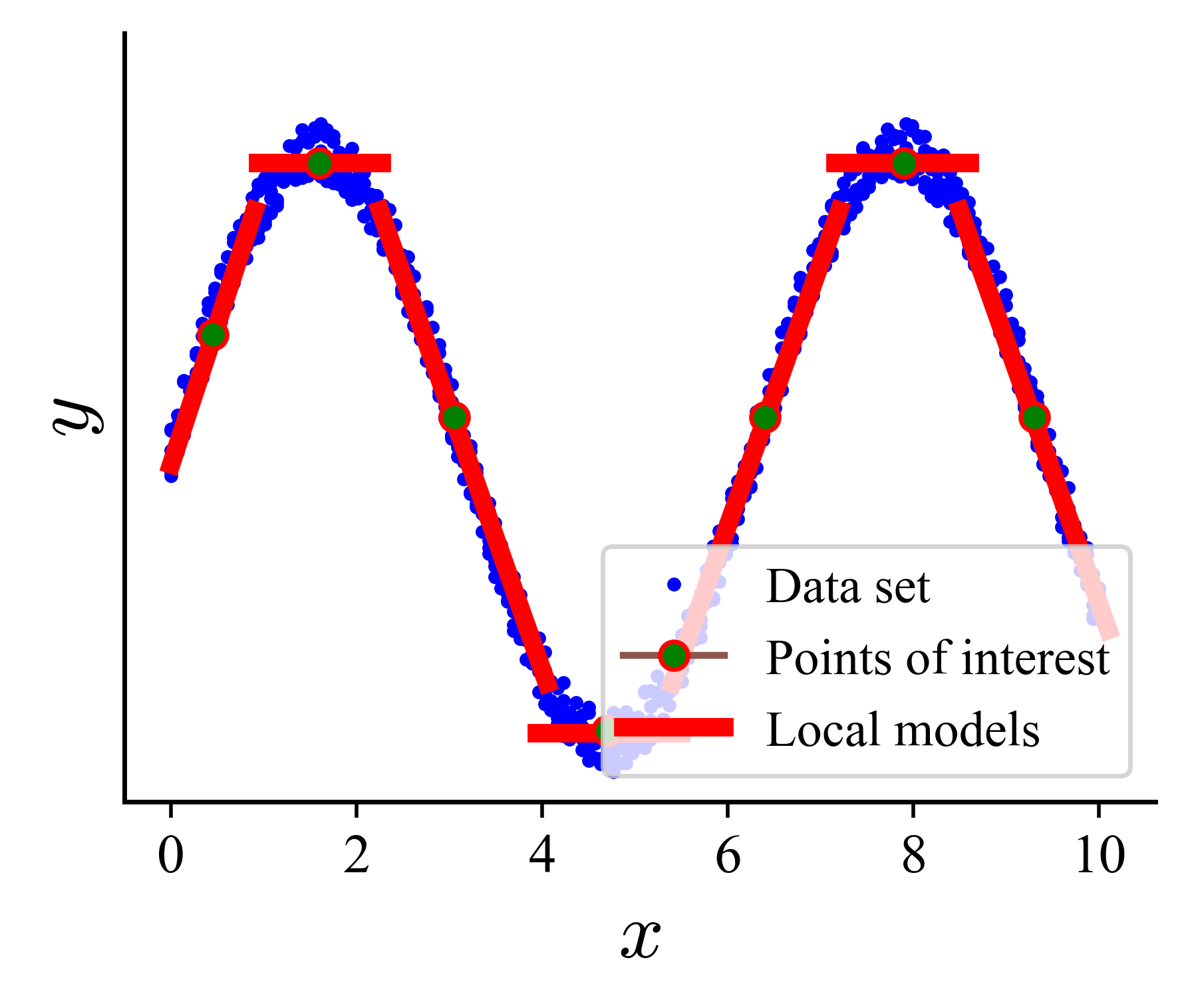

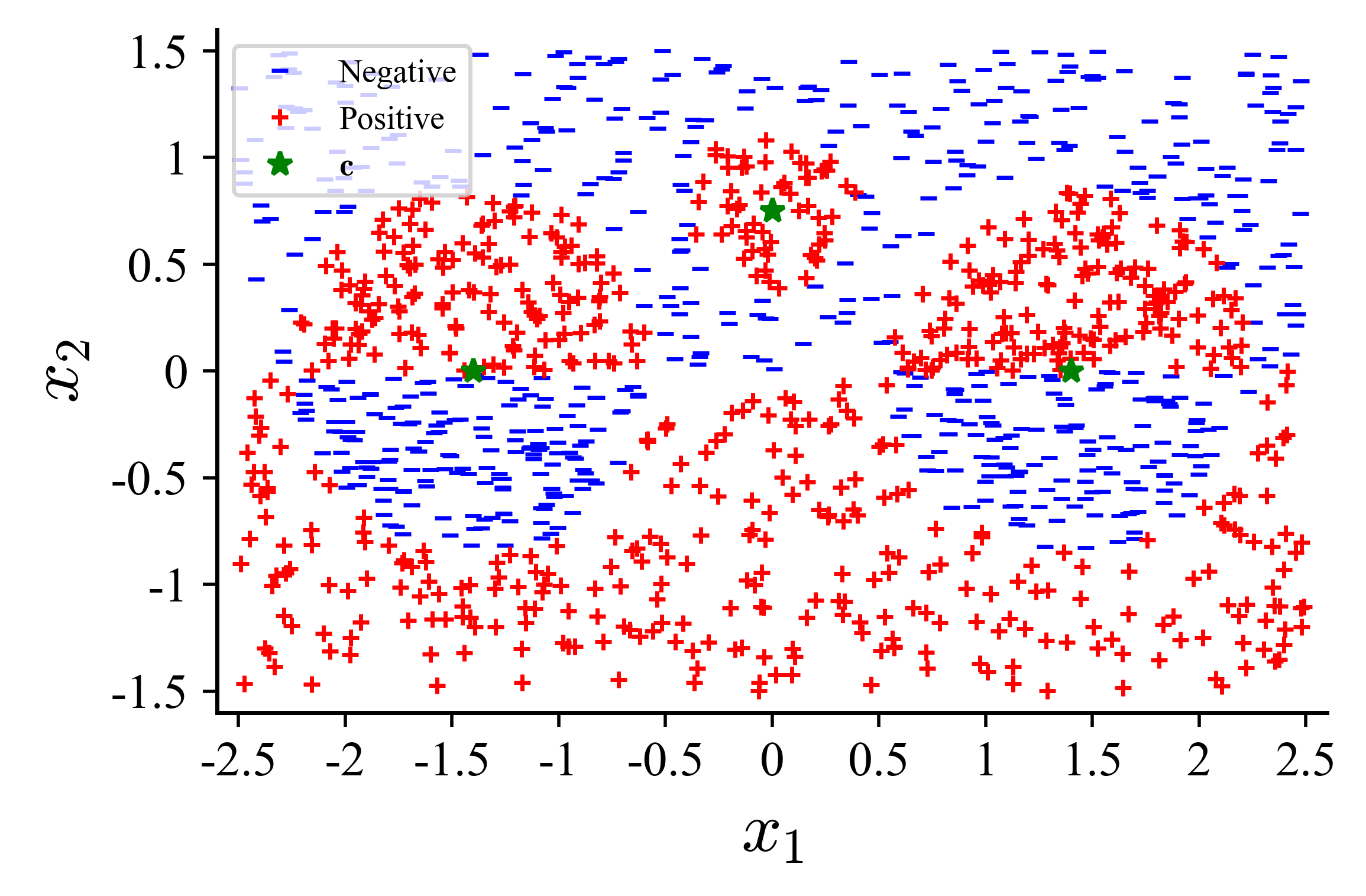

Local models within a Mixture of Experts architecture operate on a partitioned input space, with each model assigned responsibility for predictions within a specific region. These regions are delineated using Points of Interest (POIs), which serve as representative data points or centroids defining the boundaries of each model’s expertise. The selection of POIs is critical; they determine the granularity and overlap of the localized regions and directly impact the overall performance of the mixture. A model is trained to accurately predict outcomes only for inputs that fall within the proximity of its assigned POIs, effectively reducing the complexity of the prediction task and allowing for specialization. The density and distribution of POIs are configurable parameters, influencing the model’s ability to generalize and adapt to varying data distributions.

By partitioning the input space, a Mixture of Local Experts facilitates the development of models with reduced complexity within defined regions. This localized focus allows each expert to specialize on a narrower data distribution, requiring fewer parameters and simplifying model architecture compared to a single, globally-scoped model. Consequently, these simpler models are more readily interpretable, allowing for easier analysis of feature importance and prediction rationale within their respective domains. Performance gains are observed as these specialized models avoid the compromises inherent in attempting to universally model the entire input space, leading to improved accuracy and efficiency within their areas of expertise.

Defining the Boundaries of Expertise: Locality, Priors, and Vicinity

The locality parameter, denoted as β, and the associated vicinity function define the scope of localized modeling. β acts as a scaling factor, directly influencing the radius of the local region considered for each data point. The vicinity function determines the shape of this region; while often isotropic (circular or spherical), it can be anisotropic, allowing for adaptation to non-uniform data distributions. A larger β value results in a broader local region, increasing the amount of data used to estimate model parameters and potentially improving robustness but reducing local fidelity. Conversely, a smaller β value creates a narrower region, prioritizing local adaptation at the risk of overfitting to noise. The interplay between β and the vicinity function effectively controls the model’s ability to balance global generalization with localized precision.

The implementation of a Gamma prior on the locality parameter β serves as a regularization technique to mitigate overfitting in local models. This prior distribution imposes a probabilistic constraint on β, encouraging values that promote both model flexibility and stability. Specifically, the Gamma distribution, parameterized by shape (α) and rate (λ) parameters, biases the model towards locality parameters that prevent excessively small or large local regions. By shrinking extreme values of β towards the mean of the Gamma distribution, the prior reduces the model’s sensitivity to noise in the training data, thereby enhancing generalization performance and promoting the creation of more robust and reliable local models.

The implementation of an Isotropic Gaussian prior on model parameters within each local region serves as a regularization technique, enforcing a distribution centered around zero with a defined variance. This prior encourages parameter values to remain close to zero unless strongly supported by local data, preventing extreme or unrealistic predictions. Specifically, the prior is applied to the regression weights \mathbf{w}_i within each locality i, assuming a normal distribution p(\mathbf{w}_i) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^2\mathbf{I}). The scale parameter σ controls the tightness of this distribution; smaller values impose stronger regularization, while larger values allow for greater flexibility in adapting to local data characteristics. This approach contributes to model stability and generalization by mitigating the risk of overfitting to noise within individual local regions.

Beyond Prediction: Guaranteeing Generalization with PAC-Bayesian Control

The PAC-Bayesian framework offers a statistically sound approach to managing the risk associated with machine learning models, particularly when employing mixtures of local models. This methodology doesn’t simply assess performance after training; it proactively bounds the potential error on unseen data. By carefully balancing model complexity with its fit to the training data, the framework establishes quantifiable guarantees on generalization ability. This is achieved through a principled application of Bayesian reasoning and information theory, allowing researchers to optimize models not just for accuracy on the training set, but also for robustness and reliable performance in real-world applications. The resulting risk bounds provide a formal certificate of confidence, demonstrating that the model’s performance will not deviate excessively from its empirical risk, even when encountering new, previously unseen data.

Controlling model complexity is paramount to preventing overfitting, and the PAC-Bayesian framework achieves this through the strategic application of Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence. This measure quantifies the difference between the model’s predictive distribution and a prior, effectively penalizing overly complex models that deviate significantly from reasonable expectations. By bounding the KL Divergence, the framework restricts the model’s capacity to memorize the training data, forcing it to learn more generalizable patterns. This constraint ensures that the model doesn’t simply fit the noise within the training set, but instead captures the underlying signal, leading to improved performance on unseen data; empirical results demonstrate that KL Divergence can be bounded to less than 1.5x LS(Q) within synthetic data, demonstrating its efficacy in managing model complexity and promoting generalization.

The PAC-Bayesian framework distinguishes itself by offering not just predictive performance, but a quantifiable guarantee of generalization to unseen data. Through rigorous analysis, the empirical risk – a measure of the model’s errors on new inputs – is demonstrably bounded, remaining less than 1.65 times the optimal risk LS(Q) with a probability of 1 - \delta (as established in Corollary 3). This bound is not merely theoretical; evaluations on synthetic datasets reveal that the Kullback-Leibler divergence, a key indicator of model complexity, remains controlled, staying below 1.5 times LS(Q) for core components (Table 4). This controlled complexity directly translates to enhanced reliability and predictable performance when the model encounters data it hasn’t been trained on, offering a significant advantage over methods lacking such formal guarantees.

Evaluations on synthetic datasets demonstrate that this approach not only rivals the predictive performance of current state-of-the-art methodologies – as detailed in Tables 3 and 5 – but crucially, does so without sacrificing the ability to understand why the model arrives at its conclusions. Many high-performing machine learning models operate as ‘black boxes’, offering limited insight into their internal reasoning; this work prioritizes a balance between accuracy and interpretability, enabling researchers to both trust and scrutinize the model’s decision-making process. This transparency is particularly valuable in applications where understanding the basis for a prediction is as important as the prediction itself, fostering greater confidence and facilitating targeted improvements.

Beyond Interpolation: Scaling and Future Directions for Local Expertise

The core strength of this approach lies in its adaptability to diverse machine learning tasks beyond simple interpolation. By constructing a weighted combination of locally-trained models, the system successfully navigates both binary linear classification and linear regression problems without requiring significant architectural changes. Each local model, focused on a specific Point of Interest, learns to approximate the underlying function within its immediate vicinity, and the overall system generalizes by blending these local approximations. This mixture-of-experts strategy proves particularly effective when the data exhibits non-linear relationships or varying densities, allowing the model to capture complex patterns while maintaining computational efficiency and avoiding the limitations of a single, global model. The resulting performance demonstrates a compelling balance between simplicity and accuracy across a range of supervised learning applications.

The model’s adaptability hinges on a crucial parameter, ε, which functions as a dynamic confidence modulator influenced by local data density. When data points cluster tightly, indicating high certainty in a given region, ε decreases, allowing the model to express greater confidence in its predictions. Conversely, in sparse data regions where information is limited, ε increases, effectively broadening the model’s uncertainty and preventing overconfident extrapolations. This nuanced approach – adjusting predictive confidence based on the surrounding data landscape – allows the system to navigate the trade-off between bias and variance more effectively than traditional methods, ultimately enhancing its robustness and generalization capabilities across diverse datasets and varying data densities.

Evaluations in linear regression demonstrate this approach occupies a performance niche between traditional linear regression and Gaussian Support Vector Regression (SVR). Specifically, the model consistently surpasses the accuracy of simple linear regression, benefitting from the localized adaptation afforded by multiple models, yet avoids the computational cost and potential overfitting associated with Gaussian SVR. As detailed in Table 10, this intermediate performance suggests an effective balance between model complexity and generalization capability, indicating the potential for refined predictions without incurring the drawbacks of more complex methods. This positioning highlights the strategy as a viable alternative when computational efficiency is a priority and a slight increase in predictive power is desired beyond that of a basic linear model.

Continued development centers on refining the adaptability of this modeling approach by dynamically adjusting both the quantity and strategic placement of Points of Interest. This involves exploring algorithms that respond to data distribution, concentrating these points in regions of high variance or complexity to optimize model fidelity. Further research aims to integrate this localized modeling framework with external, pre-trained models, leveraging their broader knowledge to improve generalization capabilities-essentially allowing the system to combine the strengths of focused, data-driven local expertise with the robust understanding derived from larger datasets. This integration promises to overcome limitations imposed by sparse local data and facilitate more accurate predictions across diverse and unseen scenarios.

The pursuit of interpretable machine learning, as detailed in this work concerning mixtures of transparent local models, echoes a fundamental principle of resilient systems. Just as graceful decay necessitates understanding component interactions over time, so too does effective model building require localized expertise. Marvin Minsky observed, “You can’t always get what you want, but sometimes you get what you need.” This sentiment applies directly to the PAC-Bayesian approach; the method doesn’t promise a universally perfect model, but instead, offers bounded risk and interpretability – precisely what is needed for reliable performance, especially when navigating both known and unknown data points. The careful construction of these local models, and the rigorous bounds established, suggests an engineering philosophy where time isn’t an adversary, but a dimension in which system understanding deepens.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of interpretable machine learning, as exemplified by mixtures of transparent local models, merely delays the inevitable. Systems do not fail due to accumulated errors, but because time, as a medium, erodes all distinctions. This work offers a temporary reprieve – a localized understanding within a broader, opaque reality. The PAC-Bayesian bounds, while providing guarantees, describe a static snapshot; the distribution of ‘points of interest’ is not fixed, and the models will inevitably drift from optimal performance as the landscape shifts.

Future efforts will likely focus on extending these local models to genuinely dynamic systems – architectures that acknowledge and incorporate the flow of time. The current framework addresses both known and unknown points, yet assumes a certain stationarity. True robustness will require models that not only adapt to new data, but anticipate the nature of change itself. This is not a matter of increasing complexity, but of acknowledging the fundamental impermanence of all things.

The notion of ‘interpretability’ itself may prove to be a transient illusion. What appears transparent today will, with sufficient abstraction, become another layer of complexity. Perhaps the goal is not to eliminate opacity, but to learn to navigate it-to accept that all models are, ultimately, approximations of an unknowable reality, aging gracefully, or not.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10541.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Dev Plans To Voluntarily Delete AI-Generated Game

- Stranger Things Season 5 & ChatGPT: The Truth Revealed

- Pokemon Legends: Z-A Is Giving Away A Very Big Charizard

- Hytale Devs Are Paying $25K Bounty For Serious Bugs

- Bitcoin After Dark: The ETF That’s Sneakier Than Your Ex’s Texts at 2AM 😏

- Six Flags Qiddiya City Closes Park for One Day Shortly After Opening

- AAVE PREDICTION. AAVE cryptocurrency

- Stephen King Is Dominating Streaming, And It Won’t Be The Last Time In 2026

- Fans pay respects after beloved VTuber Illy dies of cystic fibrosis

2026-01-19 02:44