Author: Denis Avetisyan

New analysis confirms the surprisingly high masses and spins observed in the gravitational wave event GW231123 are not artifacts of noise or waveform modeling.

Research demonstrates the reliability of parameter estimation for GW231123, validating current gravitational wave analysis techniques against systematic errors and Gaussian noise.

Reliable parameter estimation is crucial for interpreting gravitational-wave signals, yet analyses can be susceptible to both waveform modeling uncertainties and detector noise. This research, ‘The impact of waveform systematics and Gaussian noise on the interpretation of GW231123’, investigates the robustness of inferences drawn from the exceptional black hole merger event GW231123. Through simulations using the NRSur7dq4 waveform model, we demonstrate that the observed high masses and spins are consistently recovered even in the presence of noise and across individual detectors. Do these findings validate current analysis techniques and offer a clearer understanding of extreme-mass-ratio inspirals in the broader gravitational-wave landscape?

A Novel Signal Emerges: Decoding GW231123

During the ongoing O4a observation run, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo detector network registered a compelling signal, designated GW231123. This event, potentially originating from the merger of compact objects, marks a significant addition to the growing catalog of gravitational-wave detections. The signal’s characteristics are currently under intense scrutiny, as initial analyses suggest it could represent a previously unobserved population of merging black holes or a novel astrophysical scenario. Confirmation of the event and precise determination of source parameters rely on advanced data analysis techniques and continued observation to refine the signal amidst background noise and instrumental artifacts. GW231123 provides a valuable opportunity to test existing theoretical models and deepen understanding of the universe’s most energetic phenomena.

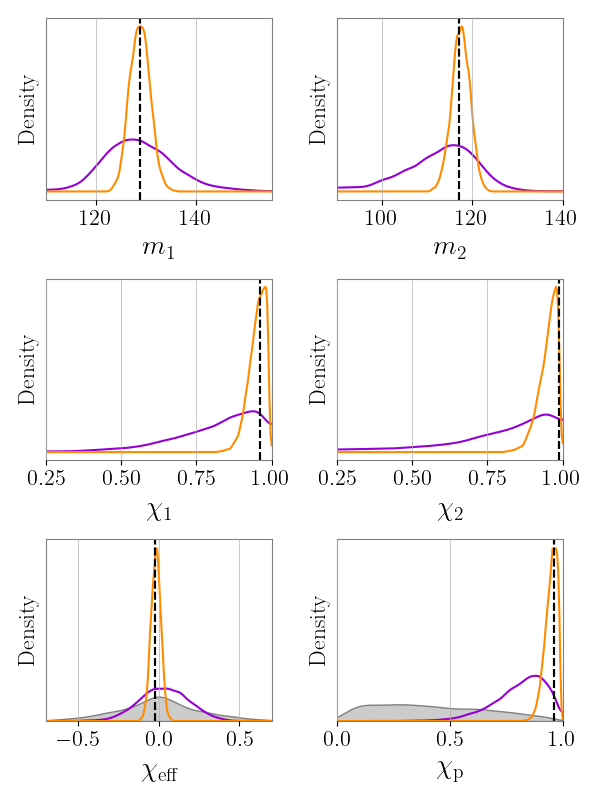

The gravitational wave event GW231123 presents a compelling anomaly for astrophysics, as preliminary investigations indicate the merging objects possess characteristics difficult to reconcile with current black hole formation theories. Specifically, the estimated masses and spins of the progenitors fall outside the expected range predicted by stellar evolution models and typical population synthesis simulations. While existing frameworks readily account for mergers involving black holes formed from the collapse of massive stars, GW231123 hints at alternative formation pathways – potentially involving hierarchical mergers in dense stellar environments, primordial black holes formed in the early universe, or even exotic compact objects beyond the standard black hole paradigm. Further detailed analysis of the waveform and source properties is crucial to definitively determine the nature of this system and refine theoretical models of black hole populations.

Accurately interpreting the gravitational wave signal GW231123 necessitates sophisticated waveform modeling, a process of creating theoretical templates that predict what the signal should look like based on the physics of merging compact objects. These models aren’t simply calculations; they incorporate complex astrophysical scenarios and require immense computational power to generate a library of possible signals. Equally crucial is robust statistical inference, the method used to determine if the observed signal genuinely matches any of these predicted waveforms, while accounting for detector noise and uncertainties. This involves techniques like Bayesian parameter estimation, which calculates the probability of different source characteristics given the data, and rigorous hypothesis testing to ensure any claimed detection isn’t simply a statistical fluke. The precision of both waveform modeling and statistical inference directly impacts the ability to confidently characterize the source and test the predictions of general relativity.

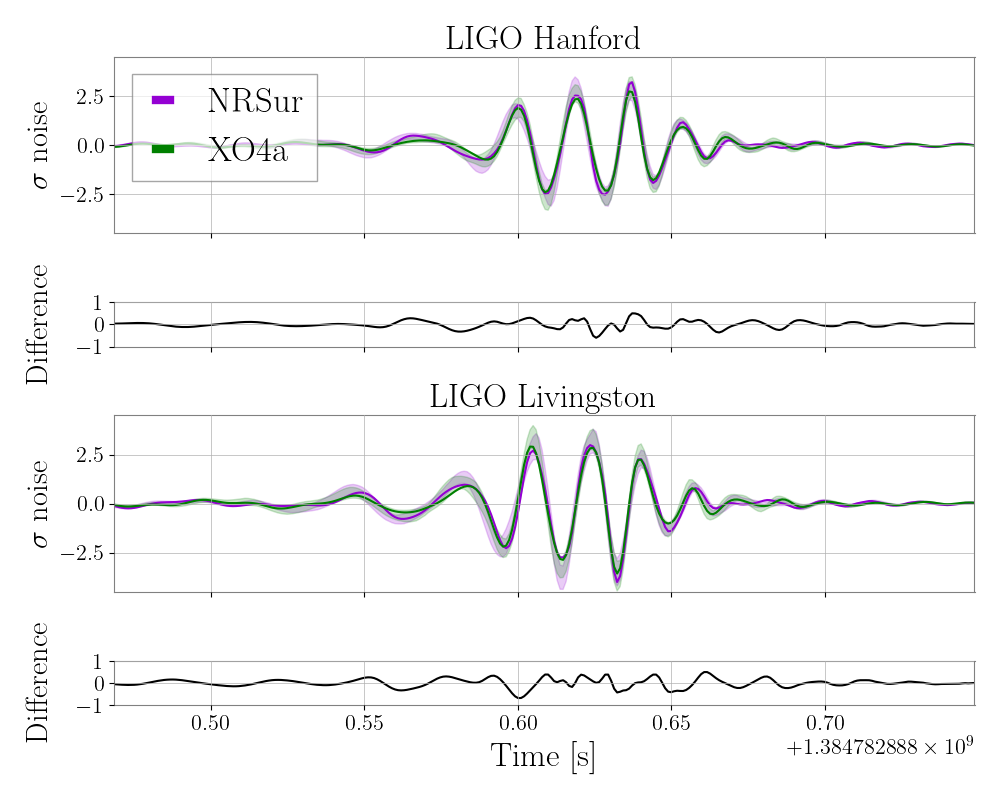

The detection of GW231123 wasn’t a clear-cut signal rising above silence; instead, the gravitational wave was subtly embedded within a significant level of GaussianNoise. Rigorous analysis focused on determining whether observed variations in the signal’s parameters – characteristics like the masses and spins of the merging objects – could simply be explained by random fluctuations inherent in this noise. To validate this, researchers performed extensive simulations, generating thousands of noisy signals. A substantial proportion – between 32 and 54 percent – of these simulated signals exhibited parameter variations mirroring those observed in GW231123, demonstrating that while the event is noteworthy, the observed differences aren’t statistically improbable given the noise environment and bolstering the need for further investigation to confirm its unusual characteristics.

Decoding Gravitational Waves: The Tools of Waveform Modeling

Accurate waveform models are fundamental to gravitational wave astronomy because they enable the extraction of source parameters – such as masses, spins, and distances – from detected signals. Models like NRSur, XPHM, and XO4a are constructed using computationally intensive numerical relativity simulations and analytical approximations of Einstein’s field equations. These models predict the expected gravitational wave signal throughout the inspiral, merger, and ringdown phases of a binary system coalescence. The fidelity of these models directly impacts the precision with which these source parameters can be determined; discrepancies between the model and the actual signal introduce uncertainties in parameter estimation. Therefore, continuous development and validation of waveform models are critical to improving the accuracy and reliability of gravitational wave data analysis.

Waveform models generate predictions of the gravitational wave signal emitted during the inspiral, merger, and ringdown phases of compact binary coalescence. These models combine two primary approaches: numerical relativity (NR) simulations, which solve Einstein’s field equations directly for highly dynamic spacetime scenarios, and analytical approximations, such as the post-Newtonian (PN) expansion and effective-one-body (EOB) formalism. NR simulations are computationally expensive but provide high accuracy, particularly during the late inspiral and merger. Analytical methods are faster and cover a broader parameter space, but often require approximations that limit their accuracy. Modern waveform models, like XO4a and NRSur, frequently combine these techniques, employing NR simulations to calibrate and improve the accuracy of analytical components, resulting in a comprehensive prediction of the expected signal h(t) as a function of source parameters like masses, spins, and distance.

Waveform models, despite their sophistication, possess inherent uncertainties stemming from approximations in numerical simulations, limitations in physics modeling, and truncation of infinite series expansions. These uncertainties manifest as systematic errors, collectively termed WaveformSystematics, which directly affect the accuracy and reliability of parameter estimation. Specifically, WaveformSystematics contribute to the underestimation of statistical errors and can bias the inferred source parameters, such as component masses, spins, and distance. Quantifying these systematic errors is crucial for robust gravitational wave astronomy, often achieved through comparisons between different waveform families and careful assessment of model assumptions.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) is a statistical method used to determine the values of parameters within a waveform model that best explain the observed gravitational wave data. The process involves constructing a likelihood function, which quantifies the probability of observing the data given a specific set of parameters. MLE then identifies the parameter values that maximize this likelihood function; mathematically, this is achieved by finding the values that satisfy \hat{\theta} = \arg\max_{\theta} L(\theta | x), where L is the likelihood function, θ represents the model parameters, and x represents the observed data. The resulting parameter estimates are those that render the observed signal most probable under the assumptions of the chosen waveform model and the statistical noise characteristics of the detector.

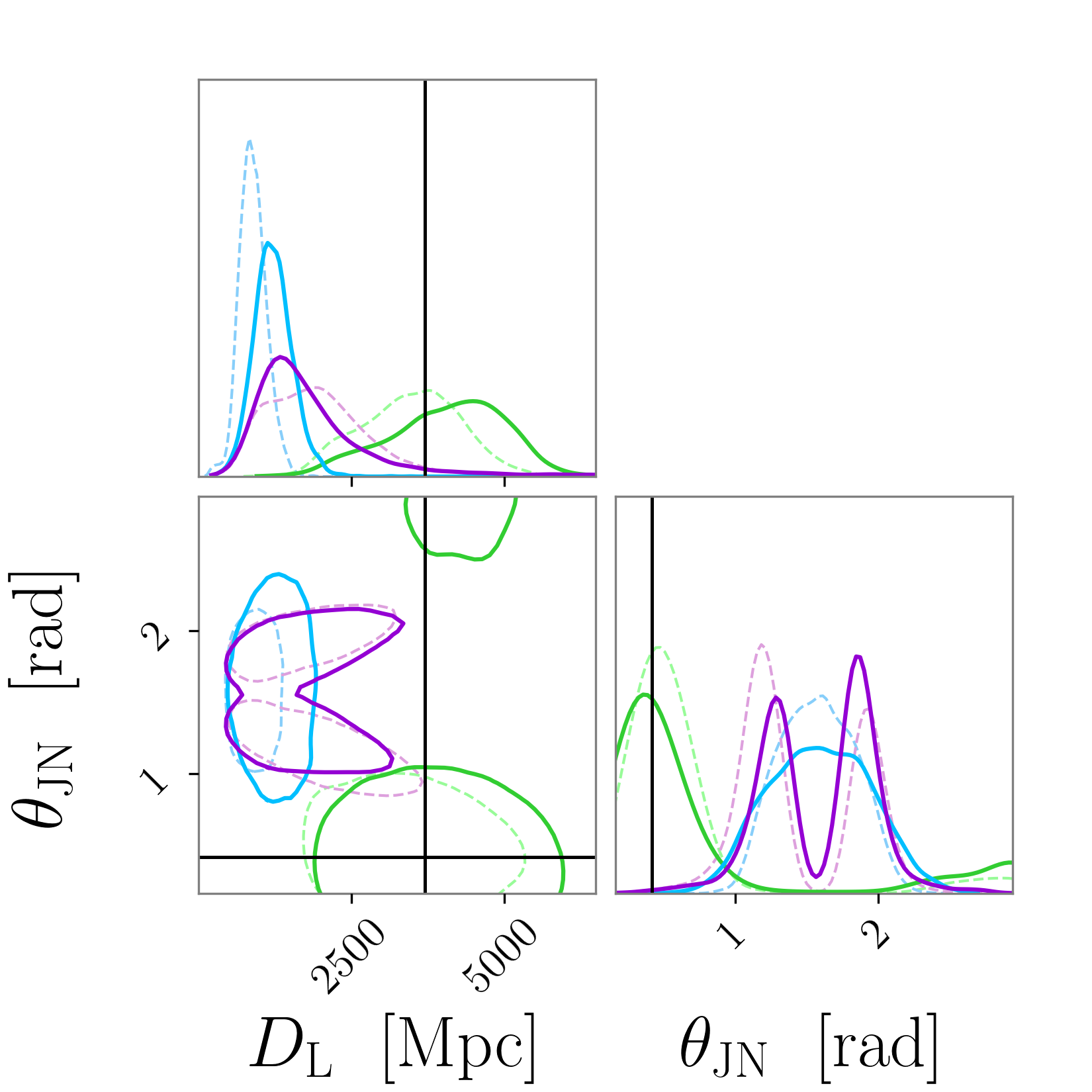

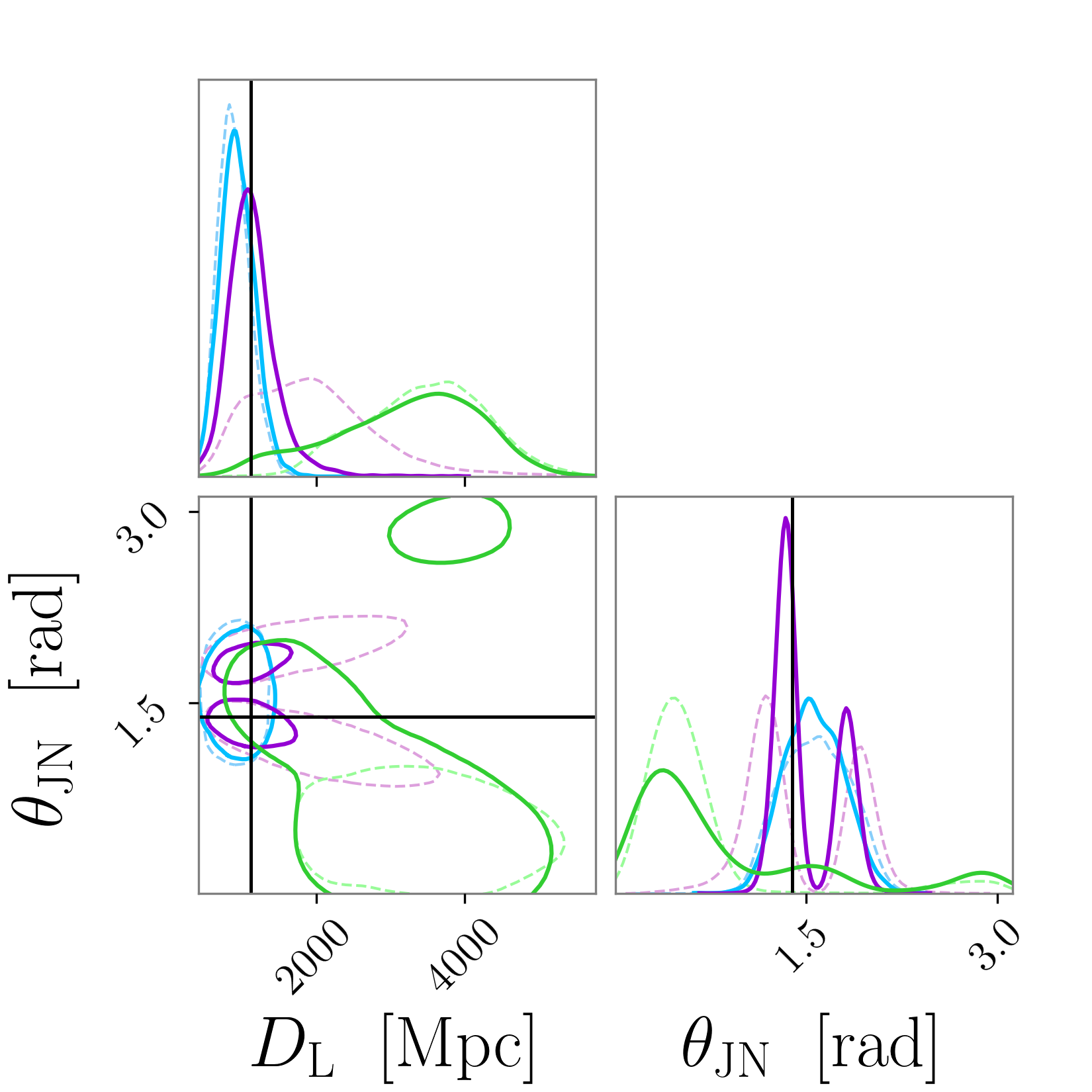

Statistical analysis comparing waveform models XO4a and NRSur yielded a Bayes Factor of 140:1 in favor of XO4a. However, researchers determined this preference stemmed from a less constrained posterior probability distribution associated with XO4a, rather than a demonstrably superior fit to the observed data. This indicates that while XO4a allows for a wider range of possible parameter values, it does not necessarily provide a more accurate representation of the source characteristics; the higher Bayes Factor reflects the model’s flexibility in accommodating the data, not necessarily its predictive power. Consequently, interpreting Bayes Factors requires careful consideration of the posterior distributions to avoid misattributing model preference to improved accuracy.

Weighing the Evidence: Statistical Inference in Gravitational Wave Astronomy

Bayes Factor Analysis is a statistical method used in gravitational wave astronomy to quantitatively compare the support for competing waveform models given observed data. This approach calculates the Bayes Factor, which represents the ratio of the marginal likelihoods of two models – essentially, the probability of observing the data given each model, integrated over all possible parameter values. A Bayes Factor greater than 1 indicates that one model is more likely to have generated the observed signal than another, while a value less than 1 suggests the opposite. The calculation inherently accounts for model complexity, penalizing models with more free parameters to avoid overfitting; this ensures that simpler models are not unfairly disadvantaged. By employing Bayes Factor Analysis, researchers can assess the relative strengths of different waveform approximations and quantify the degree to which the data support one model over another.

Bayes factor analysis quantifies the evidence for competing waveform models by calculating the ratio of their marginal likelihoods. This ratio, known as the Bayes factor, represents the probability of observing the data given one model, divided by the probability of observing the same data given another. Crucially, the calculation incorporates a penalty for model complexity, preventing overfitting to the observed signal; more complex models are downweighted unless they provide a substantial improvement in explaining the data. The marginal likelihood is obtained by integrating the likelihood function over the prior probability distribution of the model parameters, effectively averaging over all possible parameter values weighted by their prior probabilities. This approach allows for a rigorous comparison of models with differing numbers of parameters, providing a measure of how much more likely the data are under one model compared to another.

Comparison of Bayesian evidence allows for a quantitative assessment of the robustness of parameter estimation results obtained from gravitational wave signals. Different waveform models, varying in complexity and accuracy, will yield differing probabilities for the observed data. A substantial disparity in evidence between models suggests that the chosen model significantly impacts the estimated parameters, potentially introducing systematic biases. Specifically, a model with lower evidence may indicate that its parameter estimates are less reliable or that it fails to adequately capture the true characteristics of the source. This process allows researchers to quantify the uncertainty associated with waveform choices and prioritize models that best represent the observed signal, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of astrophysical inferences.

The gravitational wave event GW231123 presented unique challenges for waveform modeling due to the potential presence of high spin magnitude in the merging black holes. Accurately modeling systems with \text{spin magnitude} \approx 1 requires computationally expensive numerical relativity simulations and is subject to greater systematic uncertainties than lower-spin systems. These uncertainties stem from limitations in the available waveform templates and the difficulty in extrapolating between different simulation results. Consequently, parameter estimation for GW231123 exhibited increased sensitivity to the choice of waveform model and potential biases related to the accuracy of high-spin modeling, necessitating careful consideration of model selection and systematic error quantification.

Planned enhancements to the LIGO detector network, specifically with the implementation of LIGO A+, are projected to substantially improve the precision of gravitational wave source parameter estimation. Current mass measurement uncertainties are approximately 8%, and these are anticipated to decrease to 2% with the upgraded detectors. Similarly, uncertainties in spin magnitude measurements, presently ranging from 37% to 54%, are forecasted to be reduced to approximately 6%. These improvements will be achieved through increased detector sensitivity and reduced noise levels, enabling more accurate characterization of gravitational wave signals and the astrophysical systems that generate them.

Expanding the Gravitational Wave Landscape: Future Prospects

The next generation of gravitational wave detectors, spearheaded by the LIGO A+ project, are poised to dramatically expand the observable universe. These upgrades focus on reducing noise and increasing laser power, ultimately enhancing detector sensitivity by an estimated factor of ten. This improved capability won’t simply mean detecting more frequent events; it will unlock the potential to observe gravitational waves from sources much farther away, and those originating from less massive, and therefore fainter, mergers. Consequently, scientists anticipate a surge in detections, allowing for statistically robust studies of black hole populations and a deeper understanding of the cosmic events that ripple through spacetime. The ability to detect these fainter signals will also open new avenues for exploring the early universe and testing the fundamental limits of \text{General Relativity} .

The next generation of gravitational wave detectors is poised to illuminate the mysterious “MassGap,” a largely unexplored range between the masses of neutron stars and black holes. Current observations suggest a relative scarcity of compact objects within this mass range, but improved detector sensitivity will allow scientists to probe this region with unprecedented detail, potentially revealing a population of intermediate-mass black holes or exotic objects defying current theoretical predictions. Researchers anticipate discovering mergers involving black holes with unusual spins, mass ratios, or even those violating established astrophysical expectations – for example, primordial black holes formed in the early universe. These observations promise not only to fill the MassGap but also to challenge existing models of stellar evolution and black hole formation, offering a unique window into the extreme physics governing these cosmic phenomena.

Future gravitational wave detectors promise a revolution in astrophysics by providing unprecedented insight into the origins of black holes. Current observations suggest black holes aren’t born in a single, predictable way; instead, a diverse range of formation channels likely contribute to the observed population. Enhanced detector sensitivity will allow scientists to meticulously map the distribution of black hole masses and spins, differentiating between formation scenarios like stellar collapse, primordial origins, or dynamical interactions within dense star clusters. Crucially, these improved observations will probe the extreme conditions near black hole event horizons, testing the predictions of Einstein’s general relativity in the strong-field regime and potentially revealing deviations that hint at new physics. This refined understanding of black hole populations and the dynamics of spacetime itself will not only address fundamental questions about the universe but also illuminate the processes that shaped the galaxies we observe today.

The future of gravitational wave astronomy hinges on a synergistic relationship between increasingly sensitive detectors and sophisticated waveform models. Current detectors, while revolutionary, are limited in their ability to capture the subtle ripples in spacetime from distant or unusual cosmic events. However, as detector sensitivity improves – exemplified by projects like LIGO A+ – the need for precise theoretical templates, or waveforms, becomes paramount. These waveforms, representing the predicted signals from merging black holes and neutron stars, allow scientists to sift through noise and confidently identify genuine gravitational wave events. Crucially, advancements in waveform modeling are not merely about improving signal detection; they unlock a treasure trove of astrophysical information. By precisely matching observed signals to theoretical models, researchers can determine the masses, spins, and distances of merging objects, and even test the predictions of General Relativity in the extreme environments near black holes. This combined power promises to reveal previously hidden details about stellar evolution, black hole populations, and the fundamental laws governing the universe.

The analysis presented meticulously validates existing techniques for interpreting gravitational wave signals, a process inherently reliant on modeling complex phenomena. This pursuit of robustness against noise echoes a fundamental tenet of good system design – a structure dictates behavior. As Thomas Kuhn observed, “The more revolutionary the paradigm shift, the more resistant it will be.” GW231123, with its unusual characteristics, presented a potential challenge to established models; however, this research demonstrates that these models, while not perfect, can withstand scrutiny. If the system looks clever, it’s probably fragile, and the demonstrated resilience of current methods suggests a pragmatic, rather than overly ambitious, approach to signal interpretation.

Looking Ahead

The confirmation that GW231123’s peculiar characteristics-its place in the so-called mass gap, its spinning constituents-aren’t merely artifacts of analysis is, predictably, not a full stop. One does not simply ‘solve’ a statistical problem; rather, one refines the questions. The exercise reveals, with typical clarity, that a robust signal can emerge from a complex system, but also underscores the limitations of current modeling. The fidelity of waveform templates, after all, remains the bedrock upon which all parameter estimation rests; to presume a perfect map is to ignore the territory itself.

Future investigations must address the interplay between waveform inaccuracies and the inherent degeneracy of gravitational wave parameters. It is not enough to demonstrate that a signal is detectable; the true challenge lies in extracting every nuance of its origin. To improve is to complicate; more accurate models will inevitably demand more sophisticated Bayesian techniques to untangle their intricacies.

Ultimately, the persistent question is not whether current methods ‘work’, but rather, how well they approximate the underlying physics. The observed universe rarely conforms neatly to theoretical expectations. To truly understand events like GW231123, one must accept that the map is never the territory, and the signal, however strong, is always filtered through the limitations of the instrument-and the observer.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09678.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Complete the Behemoth Guardian Project in Infinity Nikki

- Disney’s Biggest Sci-Fi Flop of 2025 Is a Streaming Hit Now

- Pokemon Legends: Z-A Is Giving Away A Very Big Charizard

- Marvel Studios’ 3rd Saga Will Expand the MCU’s Magic Side Across 4 Major Franchises

- Chimp Mad. Kids Dead.

- ‘John Wick’s Scott Adkins Returns to Action Comedy in First Look at ‘Reckless’

- Oasis’ Noel Gallagher Addresses ‘Bond 26’ Rumors

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The Greatest Fantasy Series of All Time Game of Thrones Is a Sudden Streaming Sensation on Digital Platforms

- 10 Worst Sci-Fi Movies of All Time, According to Richard Roeper

2026-01-15 21:35